Michael DeForge's Leaving Richard's Valley is a comic strip about a group of animals who live in a commune in a park in Toronto. The leader of the commune is Richard, a shirtless human man in a long coat, who inspires enthusiastic devotion in his followers. Richard has created strict rules for those followers to improve their lives with each other and in relation to their environment. He uses progressive terms and ideas, but the community he's built is very much a cult: a cult made up of a handful of people and a lot of adorable talking animals.

When we first meet Richard's group, they're focused on purging toxins from their bodies, their minds, and their community. This means avoiding the air, the water, and even conversations between small groups of people where interpersonal social toxins like gossip can spring up. The toxins were bad for Richard in his life before the commune, and he has codified his habits into group dogma.

Richard also teaches that the stones of the park have the magical ability to get rid of toxins -- all the group's water runs through the stones, new followers are rubbed with the stones. Richard has even crafted "husbands" and "wives" from stacks of the stones like rock snowmen that enforce his rules on the group like an eco-panopticon. Richard’s group is completely insular and spends their waking hours laboring to continue to keep group members focused on Richard and his teachings.

One day, Lyle the raccoon gets sick, and no matter how much of the stone-purified water or other Richard-produced medicines he tries, his condition worsens and worsens. In desperation, some of his friends feed the dying Lyle natural "impure" water that hasn't passed through the special stones, and immediately Lyle's condition improves. However, so great is Lyle's devotion to Richard and his teachings that as soon as he regains consciousness, he hates his friends for making his body impure and damaging him in the eyes of Richard. Worse still, all of these animals have disobeyed Richard and brought toxins and doubt into the community, and so Richard banishes them from his valley.

The rest of the hefty collection is split between these exiles attempting to build a new community and the remaining members of Richard's commune as it begins to break down after this purge. The exiles wander and try again and again to establish something of their own, spinning off subculture after subculture. Richard struggles with self-doubt and feeling imprisoned by the thing he's created. The length of the story leaves DeForge room to cycle again and again through people desperately needing others, building a group, growing to resent the group, then breaking away to repeat the cycle again. A given community can only provide for so much -- a group both expands what is possible for its members and constricts them. It's a painful lesson of the world, one these characters have to keep learning and forgetting in order to navigate their personal lonelinesses.

The rest of the hefty collection is split between these exiles attempting to build a new community and the remaining members of Richard's commune as it begins to break down after this purge. The exiles wander and try again and again to establish something of their own, spinning off subculture after subculture. Richard struggles with self-doubt and feeling imprisoned by the thing he's created. The length of the story leaves DeForge room to cycle again and again through people desperately needing others, building a group, growing to resent the group, then breaking away to repeat the cycle again. A given community can only provide for so much -- a group both expands what is possible for its members and constricts them. It's a painful lesson of the world, one these characters have to keep learning and forgetting in order to navigate their personal lonelinesses.

What does it mean to exile some from a thing you no longer want to be a part of? The boundaries between in-group and out-group are maintained by a set of rules or laws and one punishment for breaking those rules is being taken from the in-group and pushed back into the out-group. The breaking of a rule means the rules no longer apply to you. The rules no longer applying to you means the benefits no longer apply to you, either. The rules give groups structure and hierarchy. They are the border between the in-group and out-group, but there's also an implied violence, a force that has to hold one identity for some at the expense of others. What's to stop someone from claiming they're part of your group when they're not? What's to stop them from taking the things that your group has built when they haven't built it? What's to stop someone in your group from changing what you liked about your group into something worse?

DeForge uses the initial Richard commune, its expelled members and their subsequent spinoff communes, cults, and art scenes to push on all these questions. We have not answered any of them. We look for sets of solutions and find ourselves walking the same circular ruts that made us unhappy, that alienated us in the first place. By packaging the entire thing as a series of four-panel comic strips, Deforge's story becomes a kind of larger gag about our quotidian inability to escape each other's stupidity because we're too stupid to not need each other's stupidity.

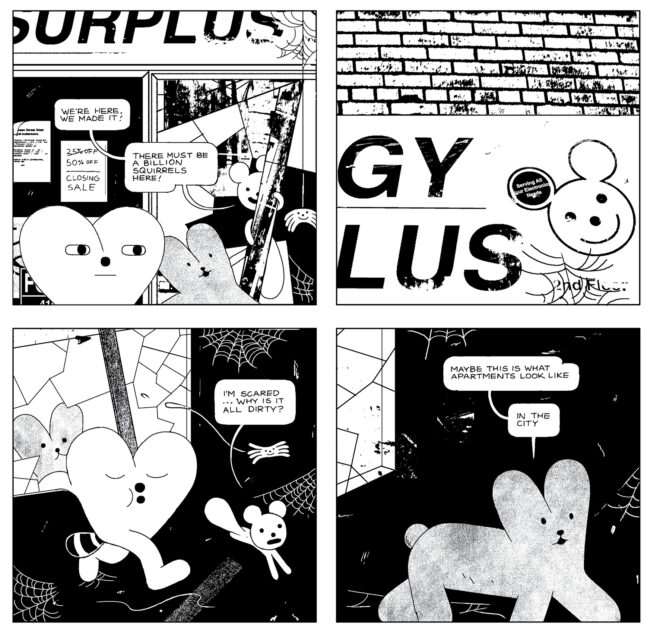

The story is built from a collection of daily comic strips (which originally appeared online) and printed to maintain the feel of individual strips within a large collective. Each page has the title "Leaving Richard's Valley" at the top, and all strips exist within the same area on the page -- centered in large gutters of white. Nearly every page is a four-panel grid, dividing the space into perfect quarters, making a balanced orderly shape for a story about attempting to construct the same in messy human interrelationships. For a comic working to deliver a difficult message about the failures of our ability to be with each other, there's a lot of seductive draw to simple visual harmonies like this. What's more, the characters themselves are simple and bendy in pleasing ways, and they speak in rigid consistent lettering.

The visual pause or rest in reading pieces that were originally serialized as individual units means the whole big book reads propulsively. DeForge is taking a whole mess of ideas about living in a world and with other people and applying his purposefully flattened and simplified visual shorthand to it. Chaotic organic shapes are flattened to tubes and spheres. For a group of animals raised under Richard's strict principles, presenting the world with that simplicity -- a world literally depicted in only black and white -- means accepting some of that mindset.

DeForge has always excelled with a purposefully flat style for his characters, making them simplistic looking and iconic. His work embraces the way this flattens out a page and creates a tension as the readers eyes must infer depth at time. Every line has a standard line weight, so there are rarely shadows to provide depth. This simple iconography means that different animal species have a kind of visual shorthand: racoons have faces like cartoon hearts with striped tails, spiders look like gloves with a simple smiley face on the palm, humans have round faces, hair, and eyes. Once this visual language is defined, the story can play against it-- Lyle looks enough like his brother, also a racoon, that one of them is drawn with the little black burglar mask markings around the eyes and one of them isn’t -- that’s their sole defining detail. As each character is struggling with loneliness and a loss of faith with often only these tiny details separating them, the mindset of each feels like one of a collective. Each member of a community is struggling with these issues in isolation, but in our capacity as reader, the similar bodies and the similar anxieties mean the whole work creates a communal wail.

Formally, then DeForge's task at hand is to undermine the pretty simplicity of the earliest strips, to problematize the simple perfections, and this is where the book’s most interesting work happens. DeForge has honed the skills to let himself hit precise marks for things like lettering and body shape over and over again. The strip that opens opens cleanly and consistently -- a single location, a small handful of characters, a set line weight, a set number of panels, etc. But once the reader's been lulled into this world, things begin to break down. Around forty pages in, there's a temporary shift to loose charcoal-y lines. Backgrounds change from drawings to over-Xeroxed photographs that have fried away most discernible visual detail. Late in the book panels stop being drawn and become photographs of sculptures of the characters. The design of the characters still match, but they've turned out from under the reader, trying on new visual identities even as they try new ways of living in relation to each other and the world.

As the strip rolls on, we stop following only the original cast. The plots keep spinning off and DeForge's eye keeps wandering down tangents of story, doubling back to pick up old threads, introducing new ways of viewing the comic itself -- sometimes it's a one-on-one confessional, sometimes a documentary, sometimes a silly gag strip. The effect is seeing a straightforward structure split and tangled into something much more interesting than stale consistency (one of the unfortunate hallmarks of long-running daily comic strips).

The story becomes an examination of what drives people to set themselves up as a leader of others to begin with. Like the groups they build coming together then falling apart, in each temporary movement leader we see a person receive some spontaneous validation, then try to build a system to ensure the regular arrival of that same validation, even though it was actually the spontaneity that made the validation first feel good. As soon as the leader can expect to be validated, that validation feels empty, and they need some other thing with no name. The rules you create to protect yourself from the world are the ones that will ultimately strangle the life from your movement.

All you can do is despair, and even here multiple characters make art or music out of frustration with this awful push-pull of individuality and collectivity only to discover the thing they created at a moment of being overwhelmed builds up followers, imitators, a whole scene that derives the wrong meaning from what was made. It's lonely to lead and infuriating to follow.