Language Barrier is a collection of four one-off full-color zines that Hannah K. Lee, a talented Korean-American Brooklyn-based artist, created from 2012 to 2017. Each of the zines has a different focus, though all carry Lee’s playfully ironic aesthetic. The zines are presented in the following, non-chronological order: Hey Beautiful (2017), Shoes Over Bills (2012), Everyone Else is Younger and More Talented (2014), and Close Encounters (2015). There’s a nice trajectory from the relatively straightforward comics that open Hey Beautiful to the typography-based poster-style visuals of Close Encounters. Thoughtfully curated and presented, Language Barrier is a groovy, pocket-sized little handbook for self-doubting, conflicted artists (and other assorted human beings) everywhere.

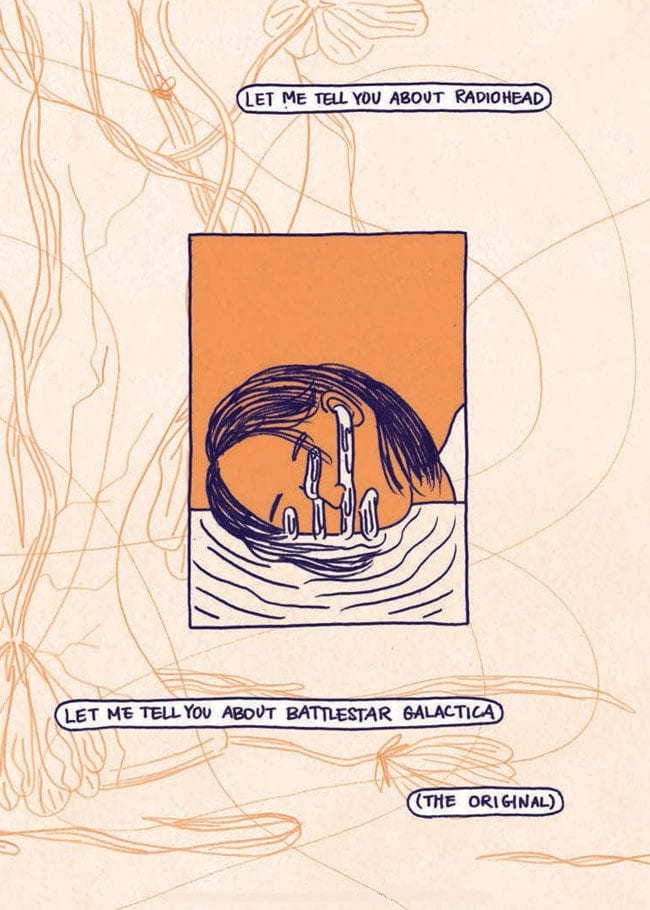

Hey Beautiful starts things off with comics and drawings on the themes of body image, dating, and sex (and the lack thereof), and the subtexts of Shit People Say, often come-ons or pick-up lines. The last is particularly important, as Lee consistently evidences a keen interest in reframing and/or decontextualizing statements to reveal their true meanings or the emotional distress they leave in their wake. A good example is a wordless pair of drawings of Lee’s face, drowning from the steady outpouring of nonsense from an unseen mansplainer. “Come over here,” he says. “Let me tell you about Kubrick.” “You’ve heard of him, right?” And so on:

Addressing objectification, Lee draws separated body parts, presented like pieces of meat to be appraised/accepted/rejected. None of us are guiltless in this area, Lee reminds us, herself included. In one comic, she is at the movies, gazing with lust at Captain America’s “glorious muffin butt,” and in another strip, “Penises 2”, she looks with wonder or befuddlement at a succession of male lovers’ appendages:

The second zine, Shoes Over Bills, juxtaposes a “follow your bliss” aesthetic (here in the form of cute shoes) with icons of often dreary necessity/responsibility. These pairings point out that the acquisition of desirable objects often requires sacrifice. In one example, Lee couples a pair of cute little slip-ons with its cost equivalent, “25 Loads of Laundry.” In another face-off, stylish thick-heeled pumps accompany a cleverly designed montage of the phrase “Credit Card Debt,” with the word “Debt” depicted lurking underwater, a warning that it awaits below to drown careless consumers. The most tightly focused of the four zines, Shoes is a clever concept, rendered with rueful humor. On-a-budget fashionistas may relate.

In perhaps my favorite of the four zines, Everyone Else is Younger and More Talented, Lee juxtaposes conceptual Barbara Kruger-esque statements with their immediate contradictions. To wit: “I love your work” is answered by “Who are you?” while “Everyone knows your name” gives over to “You will never win your father’s approval.” The final statement is simply “beautiful!” followed by “we see you.” The latter could be seen as a positive sentiment, but in each of these two images the text is surrounded by scores of rather sinister looking eyes, which multiply in the subsequent pages, ultimately taking the form of pitch black demonic figures with accusatory eyes their only facial features. There is also a drawing of discarded, burnt-out cigarette butts, embossed with words like “hot” and “good” and “art.”

Younger and More Talented coalesces two existential dilemmas. The first is that the act of creation immediately exposes the artist to the gaze and judgement of others (as the writer Shirley Jackson once wrote, “One of the most terrifying aspects of publishing stories and books is the realization that they are going to be read, and read by strangers.”). The second dilemma is the artist’s undertow that often follows completion of a work—a sense of exhaustion, dissatisfaction, or futility that can seriously deflate the artist’s sense of accomplishment. The title of the chapter encompasses all those unpleasant states-of-being with deadly accuracy.

Finally, with Close Encounters, Lee offers up a series of single words or phrases like “Nervousness” or “Sexual Tension.” This kind of text-based work can be tricky to pull of successfully (sinking into glibness all too easily), but Lee successfully creates poetic moments with clarity and insight. It’s a nice way to close out the book. With her decoded, beautifully visualized language, Lee communicates a memorably funny, insightful and humane statement about the times in which we live and our often flailing efforts at connection.