Making a book like this isn't quite a thankless task, but it sure is one bound to get nitpicked to death from every corner, so I'll start by saying I'm very glad it exists. In hindsight it seems obvious that the past two decades' reintroduction of American comics to its own history via a booming reprint market would lead to examination of said history taking place within the medium itself, but it's a gift to be cherished. I wish there were 50 books about 50 cartoonists like Tom Scioli's general-interest biography of Jack Kirby, that it was only necessary to leave the comics form for prose if one's curiosity about sequential art's past demanded deep digging on obscure figures. This book takes its place next to recent-ish comics biographies about Herge and Winsor McCay, with more in a similar vein feeling inevitable. In a way, finer points about the quality of such books are secondary to the welcome development of comics history finally finding a place within the actual comic store.

But of course we should want more than for these kinds of books to exist, we should want them to be good as well! And once this second binary is cleared comes the most difficult (and subjective) hurdle: such volumes, ideally, should carry a creative charge that harmonizes with what is found in the actual work of their subjects. In a perfect world, the biography would be as good a read as the masterworks of the creator. Might as well aim high, right? Well, spoiler alert, Scioli's Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics doesn't equal the peaks of New Gods or 2001 - but like I said, it's great the book exists at all, and it carries more than enough of its own merit to make it a worthy read.

It's tough to think of a creator better suited to Kirby as subject than Scioli. The biographer began his career as perhaps history's most painstaking pasticher of his subject's style (no small distinction when America's top comics publisher was quite literally built on people copying Kirby). As his career wore on, though, Scioli has drifted from directly imitating Kirby - at first imperceptibly and by degrees, but the contrast between inspiration and disciple this book provides is striking. Kirby may have dabbled in reminisce of Al Capone and WWII, but it's difficult to imagine him committing to the 200 pages of relatively straight historical drama that Scioli does here. Kirby was so propulsive as an artist that even when he looked back in time, his momentum rocketed his work forward. Scioli's smudgily penciled drafting might have begun as a stylistic evocation of the uninked, mimeographed pages exhibited in venues like The Jack Kirby Collector magazine, but consistent use has sanded some of its jagged edges and sharp corners off, making it ideal for a look back across the years and into the simpler time that Kirby made it his life's work to do a little complicating of. Soft bright colors that stop just within the bounds of the lush before hitting vividity provide a welcome sweetener that pulls the visuals yet further from Kirby's own. Unlike fellow Pittsburghers Jim Rugg and Ed Piskor, Scioli's approach evokes "old comics" as memory rather than sensory experience. From Kirby, Scioli has derived a unique style separate to Kirby, one that chronicles its inspiration's life with ease and vigor.

The visual style is well matched by Scioli's choice to narrate the book in Kirby's voice, a welcome departure from modern nonfiction comics' usual tiresome, personality-less third person omniscient narration. Working from a welter of interviews, Scioli approximates the "as told to" autobiography, stitching together iconic quotes and anecdotes sure to be well known to much of his audience with accurate-enough approximation on his own narrative fill in sections. Brief passages told in the voices of Stan Lee and Kirby's wife Roz are, if anything, even more compelling, and represent a road untaken: given the wealth of quotes and writing many of this book's secondary characters produced on the subject of Kirby, this biography could have provided a more well rounded view of the man as seen by his contemporaries. In this, as elsewhere, one wishes Scioli'd had more time and space. Still, the straight-from-the-horse's-

Rather bizarrely, the same can't quite be said for the drawing. Scioli's early comics (The Myth of 8-Opus, G0dland) flirt with caricature of Kirby's style, yet can't be reduced to such thanks to Scioli's depth of understanding and his own chops. But his art has evolved, and this book is as visually different from its inspiration's drawing as it is similar. Scioli's handling of his protagonist's appearance, though, is perplexing. Kirby as youth is drawn with the same sturdy, rumpled hand as everything else in the book, blending with the Depression-era background of the tale's opening seamlessly. As the book wears on, however, his features are simplified to a radical degree: his quiffed hairstyle grows mountainous, his eyes expand to dinner plates, and his fireplug stature approaches the Lilliputian. As everyone else in the book ages, Kirby kawaii's, until he resembles nothing so much as a Funko Pop. It doesn't go completely unaddressed - a scene late in the game clarifies that what we're really watching is the evolution of Kirby's eternally youthful self-image (I think?). But in any event, this element rings false in what's otherwise a sober, fact-based treatment of a life, with other such imaginative flourishes restricted to Scioli's many deft copies of Kirby's drawings.

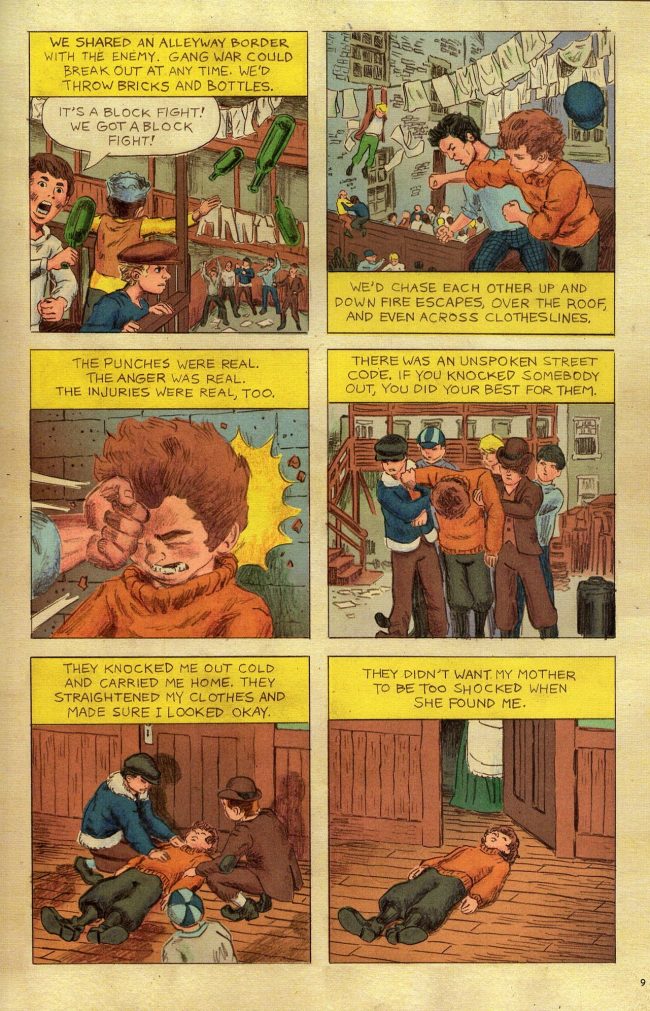

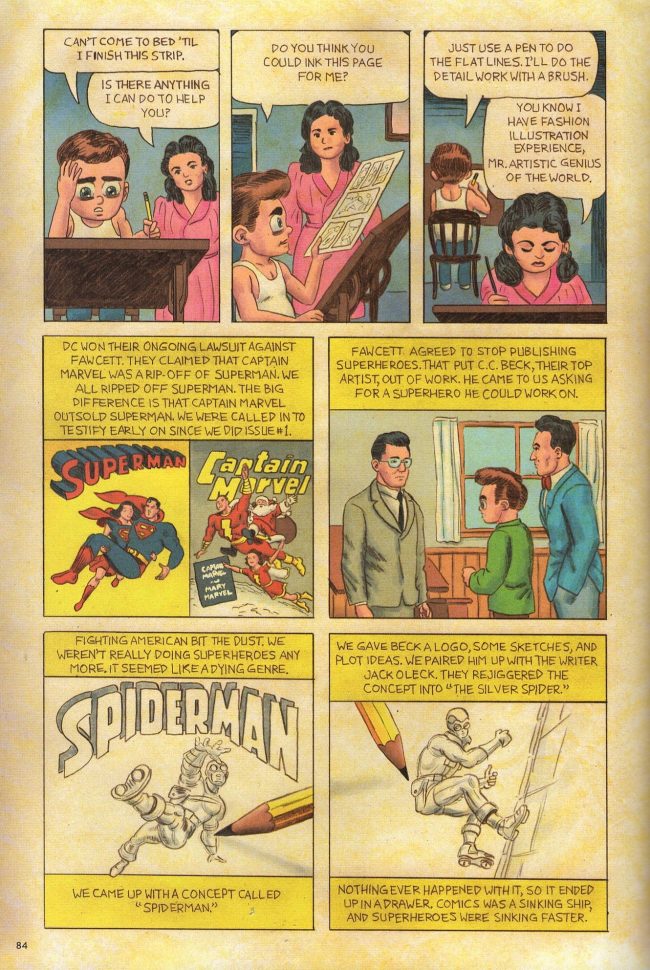

A good deal of the book's narration unspools across those copied panels, another smart choice considering the pivotal moments of Kirby's life mostly took place seated at a drawing board. Scioli never shorts the visual element of comics, with Kirby's rough-and-tumble tenure as a childhood gang member and his legitimately horrific WWII experience given room to breathe. As impressive is the character acting: Scioli nails the human drama of the all-important Lee/Kirby conflict, rendering what's become a legendary clash between two media figures whose notoriety approaches that of the superheroes they created as a traumatic personal rupture between longtime acquaintances. Kirby's even-more-important relationship, his marriage to Roz, is handled with care, neither Hollywoodized for the softies in the crowd nor treated as an inconvenient add-on to Kirby's artistic life. Here more than anywhere else on the record (except perhaps Jack and Roz's wounded, wounding 1989 interview with Gary Groth), the loving team dynamic of the Kirby marriage emerges as the backbone of Jack's life. Kirby the man is fleshed out as well here as anywhere, a significant achievement considering that panels can struggle to go as deep and detailed as prose.

A good deal of the book's narration unspools across those copied panels, another smart choice considering the pivotal moments of Kirby's life mostly took place seated at a drawing board. Scioli never shorts the visual element of comics, with Kirby's rough-and-tumble tenure as a childhood gang member and his legitimately horrific WWII experience given room to breathe. As impressive is the character acting: Scioli nails the human drama of the all-important Lee/Kirby conflict, rendering what's become a legendary clash between two media figures whose notoriety approaches that of the superheroes they created as a traumatic personal rupture between longtime acquaintances. Kirby's even-more-important relationship, his marriage to Roz, is handled with care, neither Hollywoodized for the softies in the crowd nor treated as an inconvenient add-on to Kirby's artistic life. Here more than anywhere else on the record (except perhaps Jack and Roz's wounded, wounding 1989 interview with Gary Groth), the loving team dynamic of the Kirby marriage emerges as the backbone of Jack's life. Kirby the man is fleshed out as well here as anywhere, a significant achievement considering that panels can struggle to go as deep and detailed as prose.

The book's biggest failing is one shared by prose biographies of Kirby. It lacks an in-depth critical component to satisfyingly describe what makes Kirby's work, as opposed to his legacy, important. Scioli's post-it-sized renderings of iconic Kirby panels are well done, but in their removed context they carry none of the stunning power the originals do. The adapted narration's weaving together of Kirby's thoughts on his own work is nicely put and useful, but it's a starting point and nothing more. What this text lacks can mostly be done without, but it becomes a real problem about three quarters through, once Kirby separates from Lee and leaves his famous Marvel creations for DC and his Fourth World epic. This pivotal turn of events began what I and many others see as the pinnacle of Kirby's career, an unsurpassed visionary hot streak spanning his entire DC tenure and lasting well into his return to Marvel. During this period almost every single one of the hundreds of issues Kirby put out carried at least a crackle of apparent genius, and the best of the work is still unparalleled. But without Kirby's personal conflict with Lee and the Marvel bosses making money from his sweat to push along Scioli's plot, this creative high water mark is given half as many pages as Kirby's preceding tenure at Marvel - an era with greater historical and narrative importance perhaps, but one which has less to impart to us about what makes Kirby an artist worth remembering.

As wonderful as it is that the comics form has begun to manifest a biographical commitment to the maintenance of its own history, its demonstrated ability to engage in serious self-critical work is still lacking. Quick, what's your favorite work of comics as comics criticism? I'll wait. Scott McCloud aside, we currently seem capable of commentary at best. None of this is Scioli's fault in particular, but it does place disappointing limitations on what his text can do for its subject. "The Kirby tradition is to create a new comic," the man himself is said to have opined in a famous anecdote, and while it's manifestly unfair to ask Scioli to innovate a new way of making comics as criticism while also doing a damn good biography, taking on such a monumental figure so directly is bound to invite such thoughts.

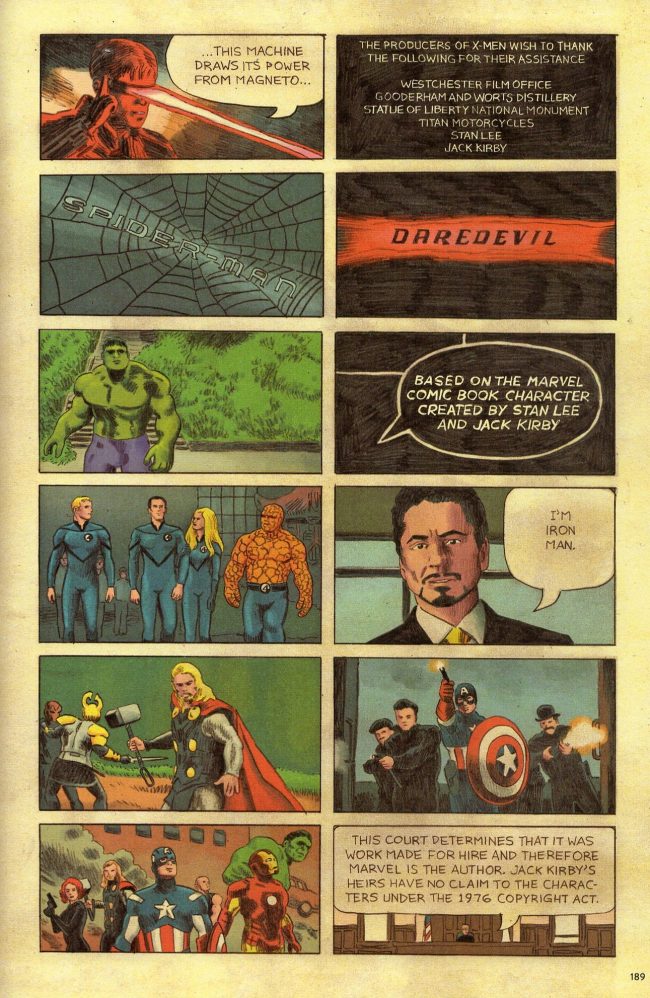

The book's conclusion is left peddling the familiar, dreary, and fundamentally incorrect construction that Kirby was important because he created popular things that made a lot of money as comics and then really made a shitload of money as movies and TV shows later on - not because he was one of the most inspired, prolific, and unique cartoonists to grace the comics medium. I get it! The first, wrong answer is historical, and thus can be laid down in panels on a page with simple visualizations of famous actors playing famous characters. The second, right answer is critical, probably best illustrated by Ken Burns panning the camera in close-up over benday dotted Kirby panels or buffed out original pages while Miles Davis plays "He Loved Him Madly" in the background or something.

The book's conclusion is left peddling the familiar, dreary, and fundamentally incorrect construction that Kirby was important because he created popular things that made a lot of money as comics and then really made a shitload of money as movies and TV shows later on - not because he was one of the most inspired, prolific, and unique cartoonists to grace the comics medium. I get it! The first, wrong answer is historical, and thus can be laid down in panels on a page with simple visualizations of famous actors playing famous characters. The second, right answer is critical, probably best illustrated by Ken Burns panning the camera in close-up over benday dotted Kirby panels or buffed out original pages while Miles Davis plays "He Loved Him Madly" in the background or something.

Now do you see why I started out by saying I'm happy this book exists? I still hold out hope for an in-depth critical monograph of Kirby, the kind of 600-page illustrated tome plenty of less important artists who didn't work in comics have been wreathed with. If a full explication of the man's genius is impossible, it'd be nice to see someone exhaust themselves getting as close as they possibly can. But in the meantime we've got this book, in which Scioli entertains, informs, and displays a lot of skill and passion in the doing of it. If it's not a thankless task, it's close, but when the worst thing you can say about a comic is that you wish there was lots more of it, that's a good sign the artist did his job.