Sam Alden is among the most gifted of the young cartoonists I've come across in recent years. He has already established a sizable, rabid fan base through his Tumblr and deservedly won the Promising New Talent nod at last year’s Ignatz Awards, amidst a strong list of nominees. The two stories featured in It Never Happened Again display Alden’s impressive strengths as a visual storyteller. They feature completely different settings and characters, but have in common protagonists in search of things ineffable—perhaps unattainable. Each story casts its own strange sort of spell, making for a very strong debut book.

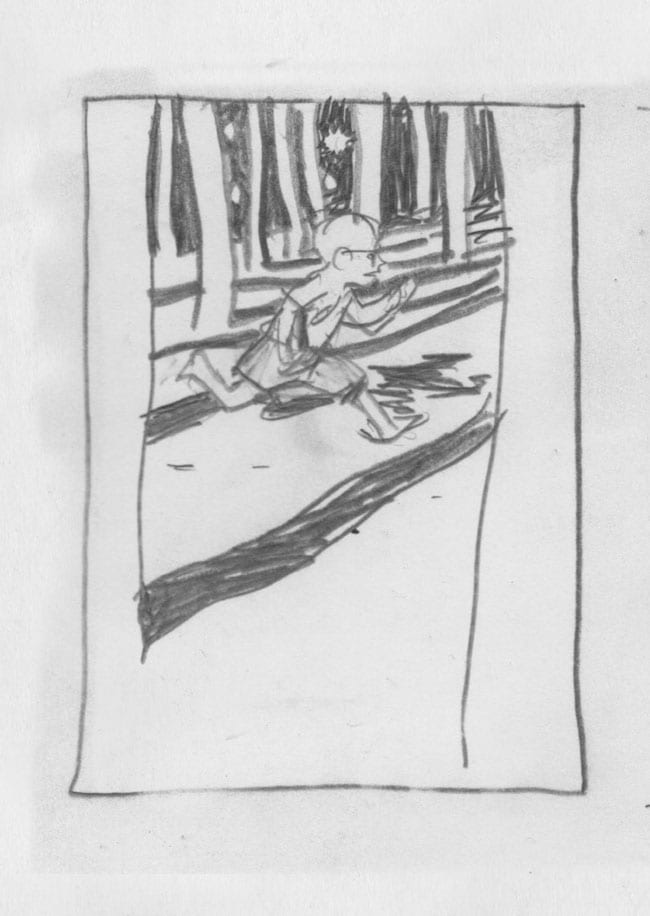

The first tale, “Hawaii 1997”, was originally published on Alden’s Tumblr and later as a mini (netting Alden the second of three Ignatz nominations in 2013, this one for Outstanding Minicomic). I have rarely enjoyed reading an online comic as much as I did this one. Alden posted it as a vertical scroll, and reading it felt like watching a mostly silent black-and-white film unreel. A simple, dreamlike autobiographical narrative, “Hawaii 1997” depicts the eight- or nine year-old Alden, bookish and a little gawky, at a Hawaiian resort during a family vacation. Early one day, he is playfully teased about his interest in a sunbathing teenage girl: “I guess he hasn't seen a lot of bikinis on the Oregon coast.” That night, he slips out of bed to explore the beach and the water. A strange, somewhat irascible young girl (close to Alden’s age) suddenly shows up. She initiates some shadow-stomping horseplay with him (“stomped your head”), then runs away, Alden in pursuit. The girl, who never offers her name, calls out to him before she vanishes into the night. Alden’s drawings of the shimmering, star-filled sky reflected on the water and the play of light and shadow on the children running are rich and tactile, evoking sense memories; you can practically feel the warm night air and hear the lapping of the salty ocean waves on the shore. The soft grays of Alden’s loose pencil work add immeasurably to the feel of a mysterious, beguiling memory. It’s a haunting piece of work.

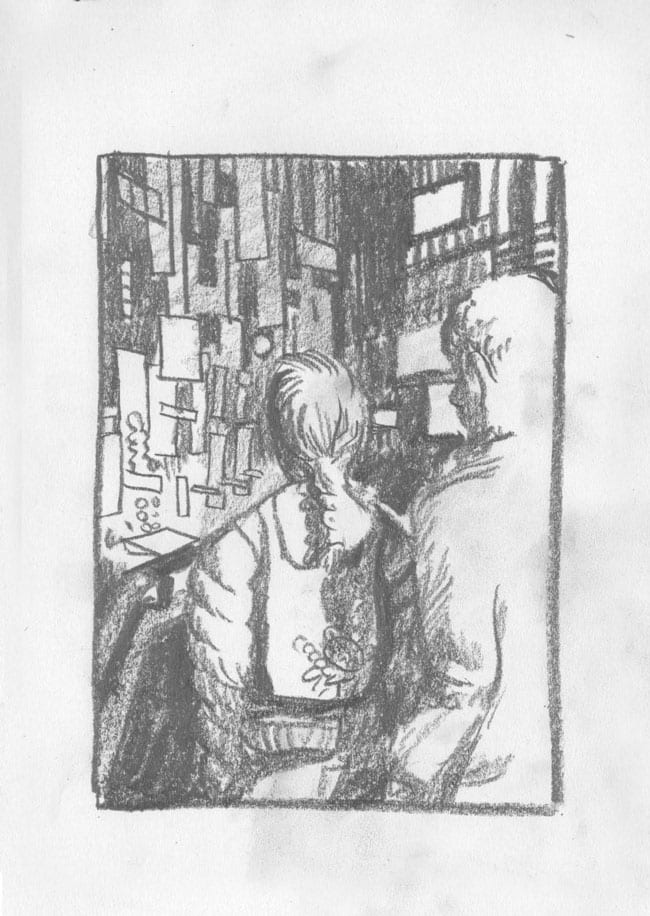

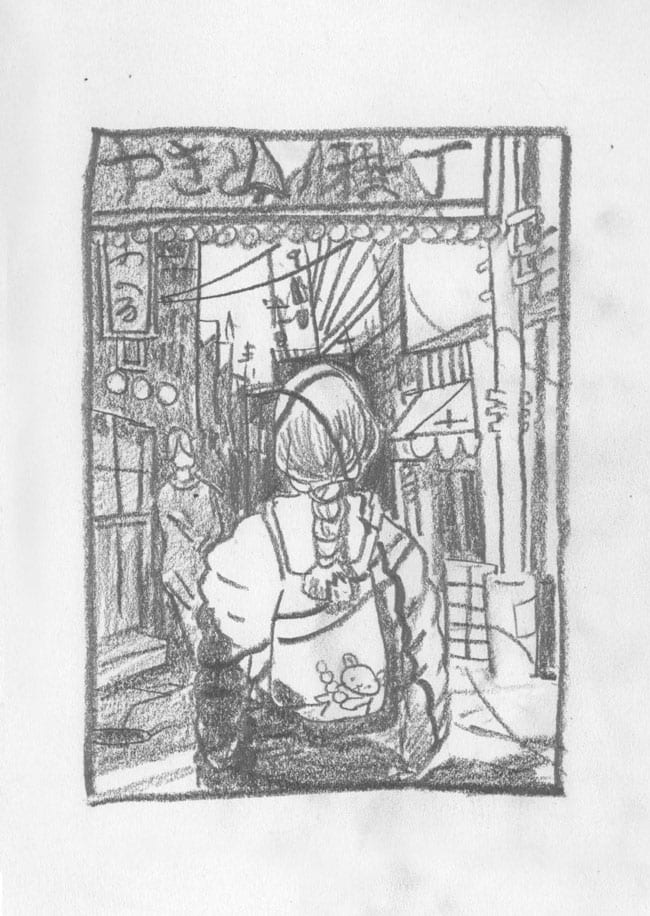

“Anime” is even better, an incisive character study and exploration of the dark side of obsessive fandom. The protagonist is Janet, a lumpish, socially awkward young woman with a consuming interest in unspecified anime programs and characters. Living with her boyfriend in his parents' basement, listless in her job, and alienated from her father, she is completely, laser-focused on a trip to Japan she has planned with her boyfriend, where she clearly expects something transformative to happen. “There’s no shame in not being smart enough to get a scholarship,” her father chides her, “but you’re 20 now and you do not even have a plan.” To Janet, Japan is the only plan she needs. Alden’s narrative drops in on progressive points in time (perhaps the span of one to two months), providing small details that paint an acutely disturbing portrait of Janet’s dissociative personality. For example: When she meets two other anime fans at a bus stop, Danielle and another unnamed girl, she gets to talking with Danielle. Janet formally introduces herself: "You can call me Kiki. And yes, that Kiki, because we are actually the exact same person. We both have braids, we were both witches when we were 13, and we both don’t fit in with the towns where we live." Danielle politely tolerates this, while the other girl recoils. Janet’s interactions with other people evoke similar reactions. Working alternately as an information clerk and Pedicab driver for a small guided tours outfit, she regularly misremembers restaurant locations and distractedly takes her annoyed passengers in the wrong direction, too absorbed in her own inner world to try very hard.

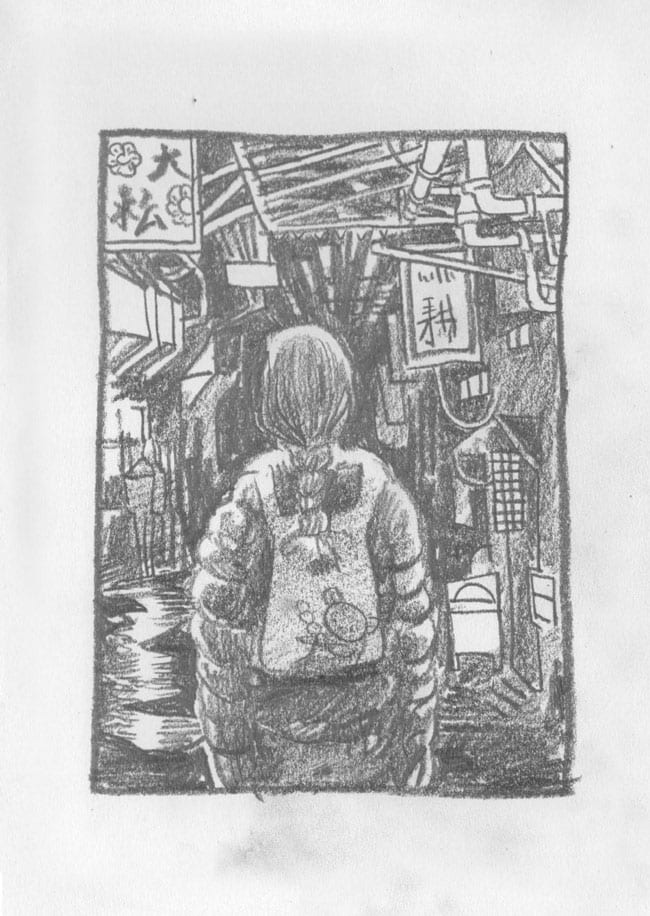

When Janet finally arrives in Japan she doesn't engage with her surroundings there either. Alden cleverly illustrates this with a series of silent panels showing her in different areas of the city, her back to the viewer in each, seemingly separated from the sensory information washing over her. She’s as much an outsider here as she is stateside.

The story ends on a small grace note, with the suggestion of some measure of happiness for Janet, but we remain highly doubtful, even fearful for what ultimately may happen to her. Though I found Janet really annoying (the same way I find, say, certain fanboys who freak out when the “wrong” actor is cast in their favorite superhero franchise), I also felt sympathy for her. She emerges as a real, three-dimensional human being, not merely a figure of scorn, as with Daniel Clowes’s infamous über-nerd character, Dan Pussey. Janet’s inability to integrate her enthusiasms into a balanced life has an ominous undercurrent of slow-building disaster. She can never seem to move forward, only retreat into fantasy, away from the outside world, with its demanding fathers, young bullies, and grasping, irritable customers. Alden has already demonstrated a keen psychological insight into damaged young people in his online stories like “Backyard” and “Household”. Eschewing narration, he conveys information objectively, allowing readers to fill in the blanks, resolve questions, and interpret to their own satisfaction. His moody, nuanced visuals and intuitive, empathetic character work in both "Hawaii 1997" and "Anime" reveal an already startlingly mature young talent. It is genuinely exciting to contemplate how he will further develop in the years ahead. In the meantime, you want to get this book.