To an extent, ish by Adam de Souza doesn’t betray an easy categorization; if one was so inclined, the closest fit might be an obliquely autobio trauma translation seen through the perspective of True Detective's Rust Cohle, the man who introduced mainstream premium cable subscribers to the concept of time as a flat circle. It’s an everything all at once narrative about the persistence of memory as one copes with grief and loss - a comic that reminds the reader of “the process, the process, the process.” This also makes ish a comic about interpretation and transformation, a work about the interrogation of pain as one journeys beyond anxiety, suffering, and sadness.

ish collects three de Souza zines: -ish (2017); and so you write it down (2018); and coda (2021). This may answer for its loose, dreamlike logic, as each story threads knots into the next with an imperfect symmetry. ish invites, no, dares the reader (not?) to use such words as “elide” and “oblique” in order to unpack its symbolism. De Souza champions feels over all else. Reading ish is like watching a Bergman film where God is in the details and symbolism and suffering are de rigueur.

The process begins when a girl receives an almost perfectly round stone that her father gives her after returning from a business trip. He knows she collects such things. Ok, relatable enough; it’s not a cute furry creature that comes with a set of arcane rules for its care, it’s a rock that’s (slightly) round or round-ish, if you like. Our precocious protagonist tries to classify what she’s received - igneous, metamorphic, a prehistoric egg, perhaps? Anxiety grows. The “rock” changes shape, first into what looks like a butternut squash, and then into a snake that slithers off the nightstand and out the door of her bedroom into her house. She follows this snake-y bit of symbolism as it makes its way to where her father is talking on the phone. His dialogue is ominous: “she will be ok? right?” and “ok I’m on my way.” The rock-not-rock disappears from the narrative, but not the symbolism, as the girl must now deal with “a sadness” that has a nature “to consume.” In four panels, she (literally) reframes her situation to understand how ‘the sadness’ could be beneficial as a balance for what’s good(?) in her life.

De Souza’s cartooning has a loose clarity that prioritizes feelings over facts; it’s like trying to analyze an unmade bed. ish looks–more to the point, feels–like de Souza has transposed his sketchbook onto the comic page with borders and panels defined as much by negative space as the actual lines, all of which leans into its feel (i.e. personality). From its freeform cartooning to the lack of capital letters and punctuation, there’s a lot of preciousness and immaturity to ish. It’s personal to a fault, and that’s fine - the raw and the personal are always welcome, but it’s not incorrect to point out that what de Souza offers is not far removed from a creative writing seminar for first-year students. Autobio comics often embrace the precious in an enveloping wooly warm hug; de Souza’s pain is valid, but is it too much to ask, perhaps, that it’s equally compelling or creative?

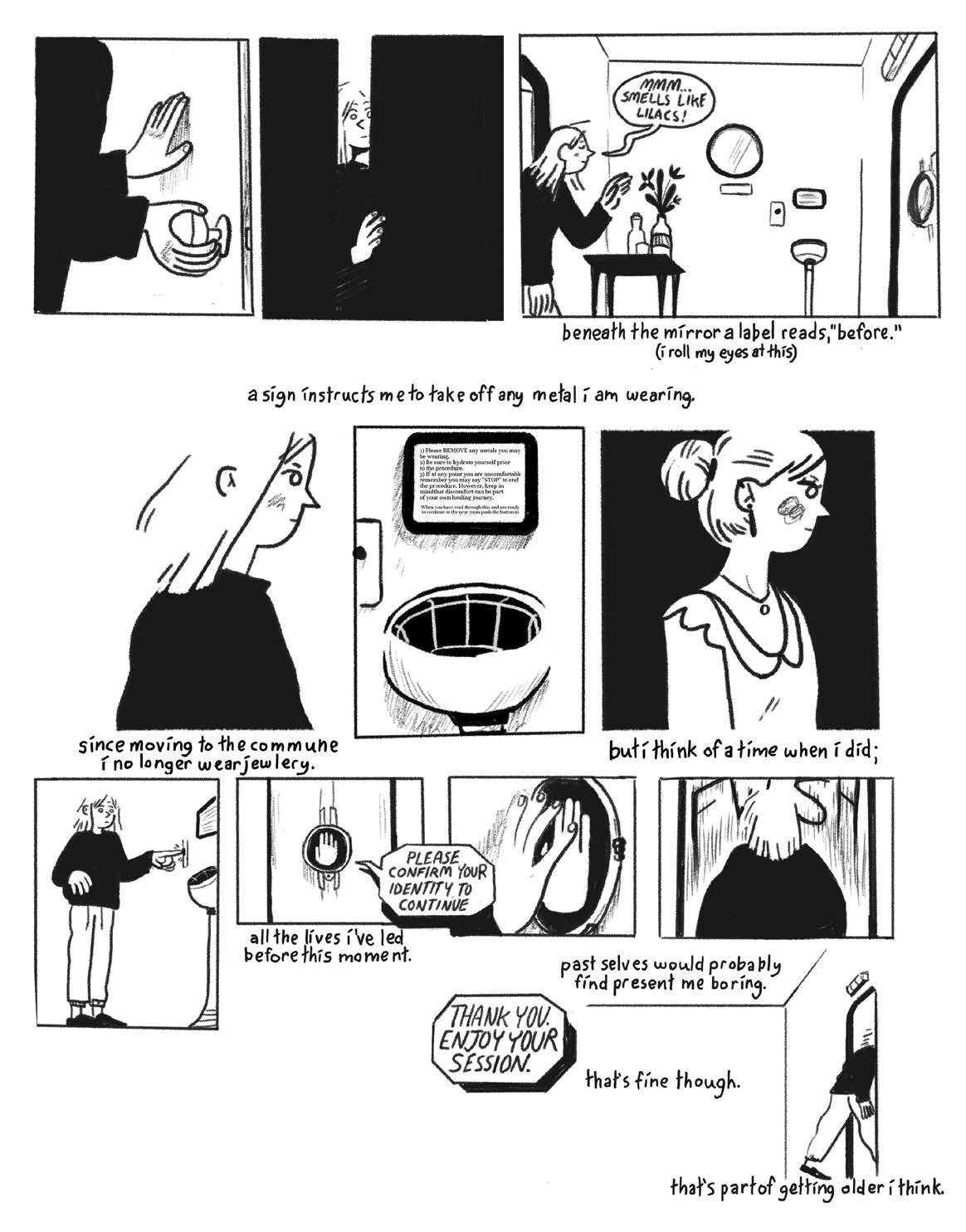

After a brief musical interlude, which will be explained in time, de Souza quits the art-as-therapy approach and sends his protagonist–now grown, in a loving partnership, and living on a commune–to something that appears therapy-ish, but isn’t. Rather than making the reader sit through a shot/reverse shot of two people talking, de Souza turns cartoonist and delivers a creative solution by implementing a more standardized comics page of gutters and panels. There's still lowercase letters hanging around in space, but not always, and there’s punctuation, and, most important, a sense of narrative propulsion. The unnamed protagonist has been spurred on by her lover and friends to try what she calls “therapy,” but is more in line with sensory deprivation. When she arrives at an office in “the city,” a disembodied voice instructs her over an intercom to remove her metal jewelry (she has none) and her bulky clothes (which she has in abundance) and put them in the “care chest” before entering “the capsule,” at which she quips: “Kind of ironic that I’m entering a literal pit to get out of an emotional one.” Once she is inside, de Souza combines the imprecise construction of the opening vignette of the young girl and the rock with a much more formal yet equally feel-focused comic. The protagonist starts to experience memories of her mother and various times in her life; she remembers riding in the backseat of a car with her mother at the wheel; she feels the cold outside while leaning her head against rain-streaked windows. All of which triggers a memory of her mother’s “grace.”

The protagonist may be a 20-ish lesbian with a yen for communal living, but the details suggest that de Souza is working through some shit - the death of his mother, perhaps, when he was a young person, perhaps. This insight is far from insightful but demonstrates de Souza’s talent as a storyteller and cartoonist to channel personal trauma into art and provide a perspective that is beyond the SOP of indie autobio comics to bleed out at the expense of a fully-formed story.

What follows is an eddy of memories as time flattens out, and, like its loosey-goosey narrative, the recall of love’s first blush becomes the last time the protagonist visited her father, which turns into a bit of storybook doggerel, and on and on, guiding our protagonist through all this like a green light on the opposite shore, to perhaps her mother’s grace.

Once the sensory deprivation session ends, de Souza takes the story back to its freeform beginning, a combination of thought-provoking images with open-ended captions like “this is the hardest part; that all things exist concurrently” and “What I am trying to tell you is bigger than any of these words.” This latter line of narration seems overindulgent and chafes against the trust de Souza has established early on in the story: that the reader will figure out what’s happening as the protagonist (and de Souza) noodle through the process of healing. If the opening with the young girl and the symbolism of the rock didn’t make it clear enough that the reader is going to have to figure out on their own what they’ve been handed, the last third of ish does so with a vengeance.

The destination de Souza settles on is where similar journeys of grief and self-discovery have ended from the time of Shakespeare to today’s plucky protagonists who fill out Pixar movies: acceptance, to an extent. Memory, de Souza comes to understand, is malleable, and so too is grief. If ‘grace’ plays a role in this final destination, de Souza seems to have abandoned it along the way for more binary concerns - “easy and hard,” “black and white.” The only certainty he feels willing or able to accept is the primacy of “the process”. All else is in-between, an endless cascade of interstices that frustratingly never reach a destination or gain any sort of knowledge. De Souza has accepted that he’s going to always be beating his boat against the current towards the green light, but he has acquired neither the self-awareness nor the willingness to know why or what it all means–if it means anything it all–to an extent.