Good comics, in whatever form they’re presented – graphic novels, monthlies, daily strips, zines, or any of their other manifestations – have to do one job that is simultaneously stone simple and devilishly complex: use a primarily visual medium to communicate a narrative story. All the best comics do this well, and all the worst don’t do it at all.

Ben Sears’ “Double+” series, released around this time each year for the last few, is indisputably in the former category. It’s probably an exaggeration – well, cards on the table: it’s definitely an exaggeration to call it one of the best comics being made right now; Sears’ talents are remarkable, but his work also occupies that porous border between good and great. While he takes care to provide enough chewy content for older readers who want to take what they read seriously, it would be a stretch to call his work thematically weighty in any meaningful sense. But it would also do him a great injustice to call it slight. Sears’ strength is absolutely as a visual storyteller, but there’s enough happening in his engaging characters, involving storylines, and light-fingered explorations of contemporary issues that the books are always something to look forward to, and the latest, House of the Black Spot, is a perfect example.

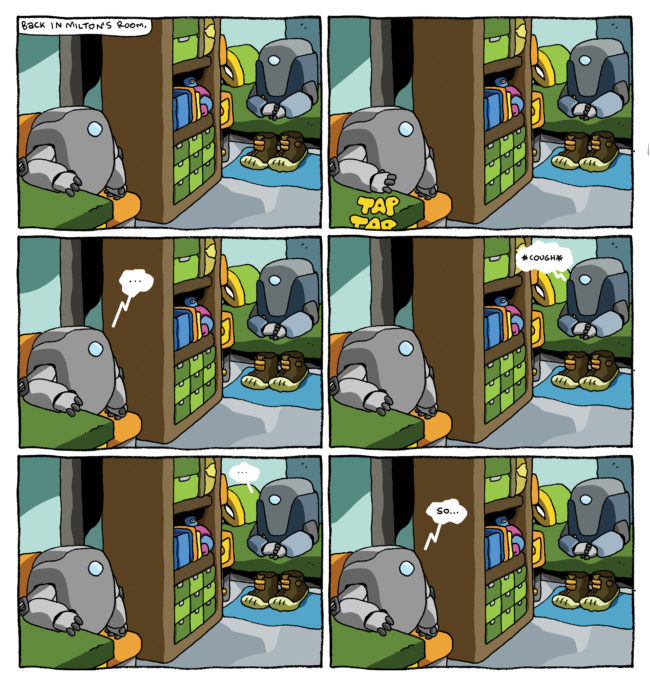

The series follows comical hero Plus Man and his mechanical pal Hank, who looks like a service droid from a long-forgotten Star Wars comic if they’d been published in Heavy Metal, as they travel to Hank’s home of Gear Town to attend the funeral of his Uncle Bill. The Double+ series take place in what could be fairly described as a high-tech magical realist setting, so you never bother to question that machines can have relatives, or that those relatives can die; you just accept it all as party of the strangeness and charm that breathes life into the universe. As it turns out, Uncle Bill was murdered, at the hands of the sinister phantom of a deceased real estate developer, who is trying to gentrify Gear Town by driving out the elderly and poor and sell their properties off to developers and their wealthy clients. It’s just a bit too absurd to be a serious examination of the issue, but it’s also too deftly handled to be easily dismissed as window dressing, giving the whole story the kind of effortless feel that makes Sears’ work always seem so simple when, in fact, an awful lot goes into it.

House of the Black Spot is an easy read, and Plus Man’s uncomplicatedly clever dialogue and the way Hank directs so much narrative pipe into ridiculous reifications of fictional tropes (the whole thing reads like a slightly silly Agatha Christie mystery if she’d had access to some of our more effective pharmaceuticals) give it a sense of humor that will appeal to younger fans. Older readers will get a jolt out of some of the jokes, the curious but effective structure, and the world Sears has built, which is crammed from one panel to the next with so many lovely little details it makes the whole experience seem much more vast than its relatively thin 80-page duration. But as fun as it is, the story is just a rail along which the art runs – and it’s in this gorgeous fusion of drawing and writing that Sears’ excellence in the medium shines through and makes his work something to always look forward to.

House of the Black Spot is an easy read, and Plus Man’s uncomplicatedly clever dialogue and the way Hank directs so much narrative pipe into ridiculous reifications of fictional tropes (the whole thing reads like a slightly silly Agatha Christie mystery if she’d had access to some of our more effective pharmaceuticals) give it a sense of humor that will appeal to younger fans. Older readers will get a jolt out of some of the jokes, the curious but effective structure, and the world Sears has built, which is crammed from one panel to the next with so many lovely little details it makes the whole experience seem much more vast than its relatively thin 80-page duration. But as fun as it is, the story is just a rail along which the art runs – and it’s in this gorgeous fusion of drawing and writing that Sears’ excellence in the medium shines through and makes his work something to always look forward to.

The style of the Double+ series isn’t without precedent; there are elements of Vaughn Bodē and Ralph Bakshi in his style, to carry it way back, and Rick Geary’s work seems forever in the background. But he has a mastery of motion simply displayed in quiet, un-busy layouts that recall James Sturm at his best. (One particular sequence, featuring Plus Man’s angst-filled daydreams as the pair flies from Bolt City to Gear Town, is almost breathtaking in its ability to take a very straightforward and efficient series of drawings and turn them into something crazy and alive.) The emotional language of comic strips (Bill Amend’s FoxTrot seems an obvious precedent) is also a clear influence, and a testament to the way a medium whose most dynamic days often seem far behind us are still influencing talented young artists.

The style of the Double+ series isn’t without precedent; there are elements of Vaughn Bodē and Ralph Bakshi in his style, to carry it way back, and Rick Geary’s work seems forever in the background. But he has a mastery of motion simply displayed in quiet, un-busy layouts that recall James Sturm at his best. (One particular sequence, featuring Plus Man’s angst-filled daydreams as the pair flies from Bolt City to Gear Town, is almost breathtaking in its ability to take a very straightforward and efficient series of drawings and turn them into something crazy and alive.) The emotional language of comic strips (Bill Amend’s FoxTrot seems an obvious precedent) is also a clear influence, and a testament to the way a medium whose most dynamic days often seem far behind us are still influencing talented young artists.

The most exciting thing about House of the Black Spot, though, is how well Sears has built on his prior work, including his terrific short story The Sweeper from a few years ago, to create a holistic story that contains everything that makes a good comic: solid storytelling, inventive ideas, strong elements of design and layout, and a well-studied understanding of what makes the narrative and the artwork enhance one another in both obvious and subtle ways. Sears has cited not just other comics artists, but graphic designers, illustrators, animators, and even filmmakers as influences, and in particular, his love of Jacques Tati’s gentle ridiculousness and situation in motion has become a strong element of his own work. While House of the Black Spot isn’t especially cinematic as the term has come to be used in comics (usually to describe the thin line between big-screen tentpoles and the superhero titles that are fodder for them), they have the pace and quality of a shambolic comedy of the old school, where everything from the set design to the body language of the lead actors propelled the whole thing forward.

The most exciting thing about House of the Black Spot, though, is how well Sears has built on his prior work, including his terrific short story The Sweeper from a few years ago, to create a holistic story that contains everything that makes a good comic: solid storytelling, inventive ideas, strong elements of design and layout, and a well-studied understanding of what makes the narrative and the artwork enhance one another in both obvious and subtle ways. Sears has cited not just other comics artists, but graphic designers, illustrators, animators, and even filmmakers as influences, and in particular, his love of Jacques Tati’s gentle ridiculousness and situation in motion has become a strong element of his own work. While House of the Black Spot isn’t especially cinematic as the term has come to be used in comics (usually to describe the thin line between big-screen tentpoles and the superhero titles that are fodder for them), they have the pace and quality of a shambolic comedy of the old school, where everything from the set design to the body language of the lead actors propelled the whole thing forward.

If Sears’ books were a little more serious about the topics they use as hooks to draw you into their worlds, so full of perfectly matched color and action, they would probably lose a substantial amount of their appeal. What they lack in weight they more than gain in lightness and brightness, in little intra-panel mysteries that are to be marveled at instead of solved, and in the generational appeal that make them such an effective interstitial to bigger and heavier works. The Double+ books have been getting better while staying familiar and comfortable, sweet snacks concocted by a chef who knows how to cook for in between meals.

If Sears’ books were a little more serious about the topics they use as hooks to draw you into their worlds, so full of perfectly matched color and action, they would probably lose a substantial amount of their appeal. What they lack in weight they more than gain in lightness and brightness, in little intra-panel mysteries that are to be marveled at instead of solved, and in the generational appeal that make them such an effective interstitial to bigger and heavier works. The Double+ books have been getting better while staying familiar and comfortable, sweet snacks concocted by a chef who knows how to cook for in between meals.