There are no words in this comic, because it doesn't need any. I don't need any either. After I bought a copy off the publisher's table at SPX the other weekend, I discovered that all I needed to do was hand this book over to people -- just for a second -- and they would actually *recoil* in amazement. Scanned images don't do it justice; this is something you have to see in person to know the feeling that overtakes you when a book lights your eyes to racing over page after page of uncanny glow. Grip is a book that vibrates, and I'm frustrated that I can't just wave it in your face, so this article will have to suffice as a next-best thing.

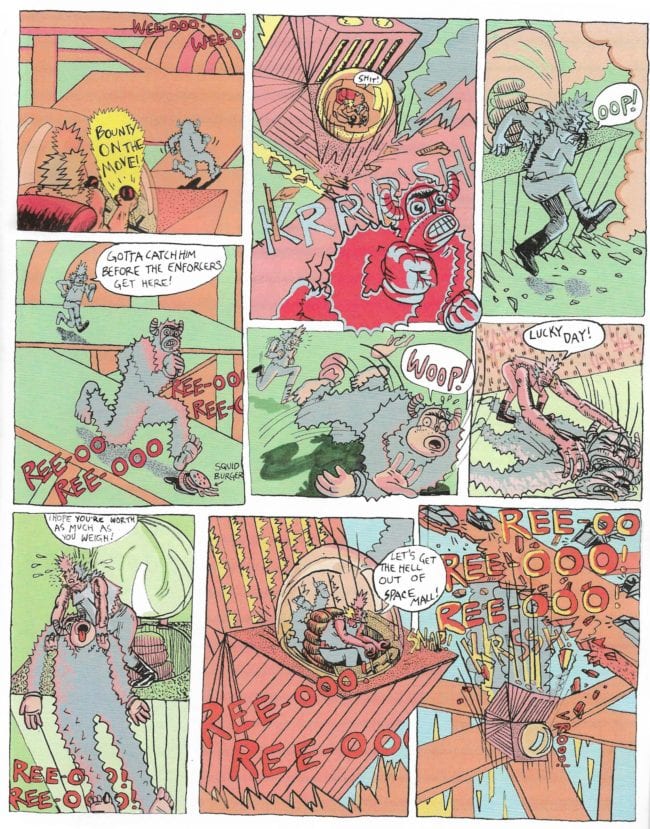

Lale Westvind is probably a familiar name to many of you by this point, in that she's done some high-profile projects of late. "The Kanibul Ball" was among the standout contributions to 2016's Kramers Ergot 9 -- a booming miniature saga of misfired empathy, hot with molten gore -- and she's the cover artist for this year's edition of The Best American Comics, in which her self-published Yazar and Arkadaş is excerpted. But this is not Westvind's first time in The Best American Comics, and her self-published works stretch back quite a few years, before even her 2012 receipt of the Ignatz for Promising New Talent for the second issue of her series Hot Dog Beach. I recently got hold of the 2011 debut number of another Westvind series, Hyperspeed to Nowhere, a color solo anthology restless in style, with stories ranging from jagged punk SF--

to evolutionary vision-questing in a Moebiusian desert of curling alien formations.

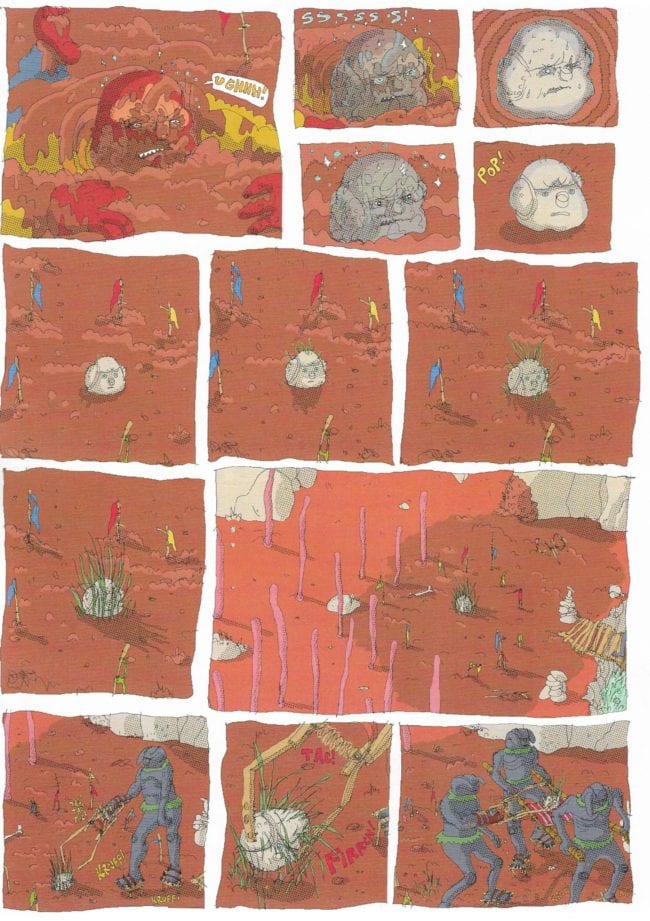

And here, in 2018, is Grip:

In the most basic sense, Grip is the story of a woman who encounters a mysterious whirlwind, a mirror consciousness which presents her with a reflection of herself, and unlocks within her the ability to stretch and curve her hands and fingers to an impossible level of dexterity - one that allows her to not only build and fix and coordinate items, but to reform matter itself. She falls in with a group of women with similar powers who inspire her first to excel in the workplace, and then to pursue visions of a magic mountain, which seems to be the source or the origin of the whirlwind. Or is the origin of this power something else?

While ostensibly the first part of a continuing series -- published as a slightly-taller-than-square softcover by Chicago's Perfectly Acceptable Press, which excels at daredevil feats of very fancy risograph printing -- Grip stands alone as a remarkable statement, one in which the artist's own hands seem to hold the entirety of American comic book history. If Westvind's Kramers story was wordy, sunburnt and hungover like a horror short running unsupervised off the Charlton press, Grip hearkens back to an even earlier time: it's like a Golden Age comic, its hero manifesting fabulous powers seemingly at random and immediately going about accomplishing mighty feats, because that's what you ought to do. It's a comic that feels like it was born unconcerned with the schematics and the expectations of comics, and therefore occupies itself with demonstrations of bravura sensation - Pure Comics Power.

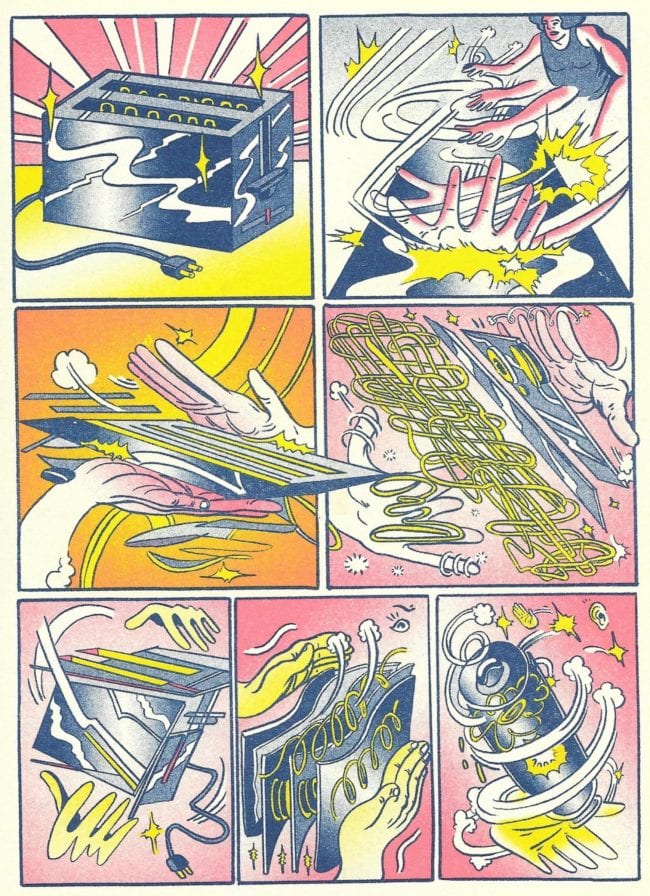

At the same time, it would be a mistake to describe Westvind's art as classicist. Back in 2015 she published a comic titled Hax with Breakdown Press, which was similar to Grip in that it was wordless, riso-printed, and focused on motion and action, though Hax adopted much more of a sequential-abstract style, where connections between panels could be discerned on a largely sensual level, as characters romp through cracking and roiling space. Grip reprises this effect, but literalizes it so that what we see as abstractions of motion can be understood as the activity of characters summoning powers from within themselves; it becomes perceptual, so that the deconstruction of a toaster into increasingly fanciful visual riffs on the component parts of its drawing (see above) is read as the racing of a character's mind as she works: the furious wonder of understanding how things operate -- of understanding that you can operate and change them -- pitched on a superheroic level.

This seems like a complicated way of saying something simple, right? We all know how Kirby Krackle works. How speed lines work - abstract elements given literal meaning by their positioning in the sequence of the work; it's the heart of comics. What is extraordinary about Grip is that it maintains this state of acute activity for the indefatigable entirety of the book, placing the sequential manipulation of objects at its very center as the engine of its narrative. The result is a *compulsively* readable comic, one that beckons you irresistibly to continue reading, because its characters never stop moving, and its world never ceases to present new opportunities for vivification. It is an ebullient comic unlike any I have read in years, and where it derives its joy is from where some other comics like it might flee in their rush toward fantasy: it is a comic about work.

Westvind dedicates the book, in significant part, to "women in the trades and anyone working with their hands." The jobs Westvind depicts in Grip are service-oriented: her hero becomes a sorter at the post office, and then a waitress, using her hands for the good of others by day; after work, characters take up welding, plumbing. One flies a plane. All are strapping, broad-shouldered women, and the way Westvind depicts them is to punctuate images of hands in close-up or near full-body images in sequence, in action, with monumental close-ups on faces to convey awe, or compassion, or simply to freeze the action in celebration of these blue-collar folks, beaming in the satisfaction of doing things well. In the whirlwind at the start of the comic, in the midst of her super-powered origin, the hero's reflection suggests that she is not being *gifted* with amazing abilities, but is ascertaining the potential within herself, and it follows that the best use of her abilities is to benefit others, as the community of women to which she comes to belong aids and nurtures her: the superhero as most excellent public servant is a rare emphasis.

But Grip is also about the hero pursuing the evolution of the self, like in many of Westvind's comics; "The Kanibul Ball" presented an especially dark and futile resolution, and this is the positive obverse. To work, to derive satisfaction from good work, in Grip, is to harmonize the mind and body so that the stuff of the outside world is receptive to your touch; in formal terms, Westvind conveys this by pushing her own cartooning into abstracted flights of excited motion, the pleasure of these agile drawings communicating the ultra-concentration and supreme competency of doing things well, the power and joy. In story terms, the plot breaks off in the second half to follow the hero on a quest through rustling woods and up spiky peaks, the blue, red and yellow of the risograph ink mixing pale like fading colors on newsprint, but maintaining a hum -- I have no better word than hum -- that speaks of a massing potential energy. Soon, there are visions. You will know what the visions are, because the panel borders CATCH FIRE like steel lines soaked in kerosene, and Grip is the rare comic where such a gesture feels entirely in keeping with the trajectory of the story as drawn.

"I believe that your thoughts completely affect your reality," Westvind remarked to Karen Peltier, four years ago on this site. It would be facile to conclude that this book is the artist's celebration of what she can do with her hands, but I'd hate to leave anything out. And anyway, Westvind's characters do not dominate the world in which they exist; they exist instead in a continuum of activity, swept along in dialogue-free conversation with matter itself at the boltcrack pace of the artist's panels. What is most special, most fascinating about this fireworks show of a book, is that everything it does feels necessary to convey the information it wants to give you; it cannot help but be this thing. It is the thing that Westvind had to make, and to look at it is to feel as if comics are re-formed before you, as fast as your fingers can move.