Graphic Witness: Five Wordless Graphic Novels contains a selection of stories told through engraving and relief printing, and united in their humanist sensibilities and moral outrage. Now in its second edition, the collection has added Erich Glas’s 1942 story in reliefs “Leilot” to works from Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward, Giacomo Patri, and Laurence Hyde. Altogether, these pieces date to between 1918 and 1951; that is, from the aftermath of World War I to the years following the first uses of the atomic bomb. They are, as the title suggests, all efforts to bear witness, and in their visual accounting of societal ills, they range from historical curiosities to works of great potency.

In part because these pieces are literally wordless, with no narration or dialogue to interrupt the echoes of the book’s frontmatter, the preface from engraver and professor George Walker may exert a stronger influence on readers than such features usually do. Although the stories command attention on their own terms, questions of where a person locates these works relative to the modern graphic novel, and how much influence readers should understand them to have had, are perhaps inevitable. Still, Walker’s preface is arguably a messy act of table-setting. He identifies Belgian artist Masereel as “the grandfather of the modern graphic novel” and refers to “the adult graphic novel tradition begun by [Masereel],” noting elsewhere that “wordless novels are not books for children—or ‘comic books,’ as we might define them today. They are sequential art for adults.” He is not wrong to differentiate the works in Graphic Witness from the newspaper strips or children’s adventure comics of their era. With respect to tone and to the use or absence of numerous formal devices, they diverge significantly. But to the extent Walker suggests a history of the graphic novel with Masereel as its fountainhead, he is not convincing.

Consideration of what Walker means by graphic novel highlights what he omits from the category. His list of modern exemplars of the form is—almost to the person—what you’d imagine from someone preoccupied with perceived respectability and with limited curiosity about comics: “Neil Gaiman, Alan Moore, Joe Sacco, Harvey Pekar, Frank Miller and Chris Ware.” (It is possible that this list has not been updated since the 2007 edition, but if so, that’s a misstep of its own.) Prior to this, he mentions Eisner and Spiegelman in a survey of the graphic novel that skips some decades entirely. To the extent readers find a history of the graphic novel in Walker’s preface, it is a history unwilling to recognize that the graphic novel was built upon “comic books” too. Giving Masereel the status of graphic-novel granddaddy requires a flattened version of comics history, and as such, it does Masereel and the book’s other artists (or its readers) no favors.

Much better is Walker’s introduction, following the preface, in which he discusses the artists’ block carvings as block carvings. Here he provides insight into carving techniques and relief printing as well as the distinct but sometimes overlapping contexts of the collection’s artists. Later, an afterword by Seth resumes inquiries into the pieces’ connections to comics, but with more nuance. Acknowledging the pieces’ obvious drawn and sequential qualities, Seth differentiates them from contemporaneous comics art in terms of influences and aspirations—but notes that the art of Masereel, Ward, et al. have “still been adopted by modern cartoonists hungry for ancestors.”

Graphic Witness presents its works chronologically, beginning with Masereel’s 1918 “The Passion of a Man.” Its placement accentuates the strengths and deficits of “Passion.” A reader can see its influence borne out across later works—at minimum, Masereel’s prescience—but also that “Passion” is technically less accomplished and narratively less complex than the works that follow. The story’s twenty-odd pages present a kind of boilerplate social realism. Borne out of wedlock and into poverty, its lead figure attempts to eke out a living, steals to survive, spends time locked up, and finds solidarity among other members of the working class before winding up in front of a firing squad.

Ignoring a comics connection or lack thereof, and considering “Passion” solely by the term wordless novel or picture novel, makes those terms seem a bit specious; by many definitions of the novel, there is little of it in this brief, blunt sequence. More accurate is Thomas Mann’s early verdict that the engravings form “a silent film […] without titles.” If a person were to compare Masereel with contemporaneous cartoonists, they would see higher levels of craft in the theoretically lowlier strips of George Herriman or Windsor McKay.

If the pages of “Passion” can read as simplistic, however, its directness is also an asset. Perhaps most striking is a page on which a police officer nabs the lead for stealing. Hulking over the emaciated young man in pyramidal fashion, his heft beginning at trunklike legs and coming to a point at his Belgian officer’s cap, the officer is an effective stand-in for the threat of force against dissent on a grand scale. A sea of bowler hats flows back behind the pair, further emphasizing the officer’s role as a buffer between the impoverished lead character and class stratum above him.

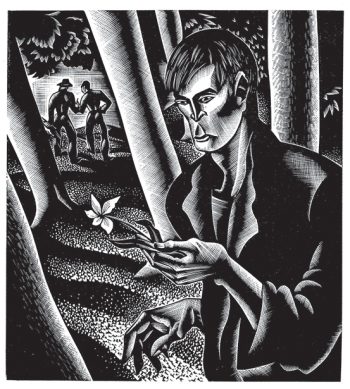

Lynd Ward’s “Wild Pilgrimage” (1932) is a more refined work but also more dynamic. Like “Passion of a Man,” it follows a young man searching for autonomy and a way out of industrial drudgery. He first leaves the city for life outside of it, taken in as a farm laborer and then expelled for a roll in the hay; later, he’s drawn into the concerns of workers as a collective and drawn into combat with authorities because of it. Throughout its pages, Ward combines representational and figurative scenes, balancing economic concerns, erotic concerns, and dream imagery.

Lynd Ward’s “Wild Pilgrimage” (1932) is a more refined work but also more dynamic. Like “Passion of a Man,” it follows a young man searching for autonomy and a way out of industrial drudgery. He first leaves the city for life outside of it, taken in as a farm laborer and then expelled for a roll in the hay; later, he’s drawn into the concerns of workers as a collective and drawn into combat with authorities because of it. Throughout its pages, Ward combines representational and figurative scenes, balancing economic concerns, erotic concerns, and dream imagery.

“Pilgrimage” is decidedly irony-free; Thomas Wolfe’s descriptions of young men chartering their destinies amidst the currents of darkness and time reverberate here, and Ward renders his protagonist a statuesque figure of masculine vitality to a near-parodic degree. But it is also a wonderfully committed piece of art. Ward reveals an undeniable gift for atmosphere in its pages, first in its oppressive industrialized cityscape and later in marbled country skies and forests of impossible denseness. He pairs this with an attunement to human physicality. The everyman of “Pilgrimage” may appear to be made of bronze, but the story’s heightened-ness is inseparable from its depth of feel. When Ward tilts toward abstraction, it’s according to specific values and a specific vision.

The delineation between realistic and symbolic imagery is more rigid in Giacomo Patri’s “White Collar,” from 1938. This story follows a member of the middle class who struggles to maintain his footing, in a visual argument from Patri that white-collar workers have as much to benefit as anyone from unionization. Patri’s composition are less transporting than Ward’s, but his beat-by-beat storytelling is strong—including a segment on the specific challenges of an unplanned pregnancy that momentarily broadens the story’s perspective to that of the man and his wife. Patri punctuates his vignettes of economic hardship with visual metaphors that are sometimes heavy handed but are highly potent too, e.g. a hand holding a whip as it emerges from a clock face, keeping the story’s beleaguered advertising illustrator on task.

Although every piece in Graphic Witness reflects some concerns of its era, “Leilot” by Erich Glas is the most remarkable historical artifact in the collection. Completed in 1942, “Leilot” sees Glas drawing from accounts of the Holocaust to that point and from the literal fever dreams that preceded his first sketches. As a document of his fears of mounting atrocities, and—in its final pages—of hopes for resistance and resilience, “Leilot” makes a singular impact among the collection’s surrounding works. It is notable not only for its timing (which predates the widespread availability of images from the Holocaust) but for what Glas accomplishes as an engraver. Each linocut includes scenes of intense physicality, as well as a gravity and immediacy not just lent by context but projecting out from Glas’s compositions.

The collection’s final piece, Hyde’s “Southern Cross” (1951), confronts a different moment, a 1946 hydrogen bomb test by the US military at the Bikini Atoll. Hyde’s piece resembles Ward’s “Pilgrimage” in its combination of vibrant backgrounds and dynamic figure carving, although in the case of “Southern Cross,” Hyde carves less delicate, almost violent arrays of lines to animate his South Pacific skies, and his figure work often involves reducing figures down to a set of defining shapes rather than adopting Ward’s extreme angularity. At times, Hyde’s backgrounds are stormy to a fault; midway through the piece, it is briefly difficult to discern whether a reader is seeing the bomb test in action or a preceding storm at its most severe. But his depictions of the test result’s are effective, upsetting without ever losing their compositional elegance. And unlike some of the other pieces, “Southern Cross” sees Hyde using a ironist’s touch in places. Midway through a US soldier’s explanation of the upcoming test to local inhabitants of the atoll, Hyde places an engraving of a dove atop a plummeting bomb, then of angels trumpeting their horns, in a bitter pair of images that undercut whatever words a reader might imagine the solider is delivering.

As an act of curation, Graphic Witness trips on its toes in the early going but nevertheless delivers a valuable collection of works. Taking these pieces together, as Graphic Witness does, allows a reader to appreciate distinct sensibilities among the artists but also successfully suggests a kind of shared purpose. Even if a reader regards the pieces as part of a side story in the history of the graphic novel, not as its most foundational works, well, it’s still a good story. A story of artists, from a number of countries, seizing on shared tools and techniques to create a venue for their outrage. And the works themselves—using silence, gesture, negative space, and heavy blacks to various strong effects—are alert both to the injustices of their time and the potential of their form.