Craig Thompson has led a fascinating life, and he depicts it with courage. Raised in the tiny town of Marathon, Wisconsin by Evangelical parents, he recorded his childhood sexual trauma, first love and subsequent break from the Christian faith in the phenomenally popular book Blankets, released in 2003, when he was only 28.

By the time my mom gifted me the book, I was a college sophomore deeply invested in the aesthetics of punk and noise rock. I found the story compelling, but I recognized that Thompson’s more polished artwork would never appeal to me in the way that, say, Brian Chippendale’s scratchier, more expressive linework made my blood sing. I also recognized this as a matter purely of personal taste. Thompson’s skill as a draftsman is undeniable. He has a level of technical ability that only a handful of artists in any generation possess, and when he’s telling personal stories, his honesty and candor give the work pathos and gravitas. Blankets had a profound cultural impact: it introduced a generation of young readers to graphic novels.

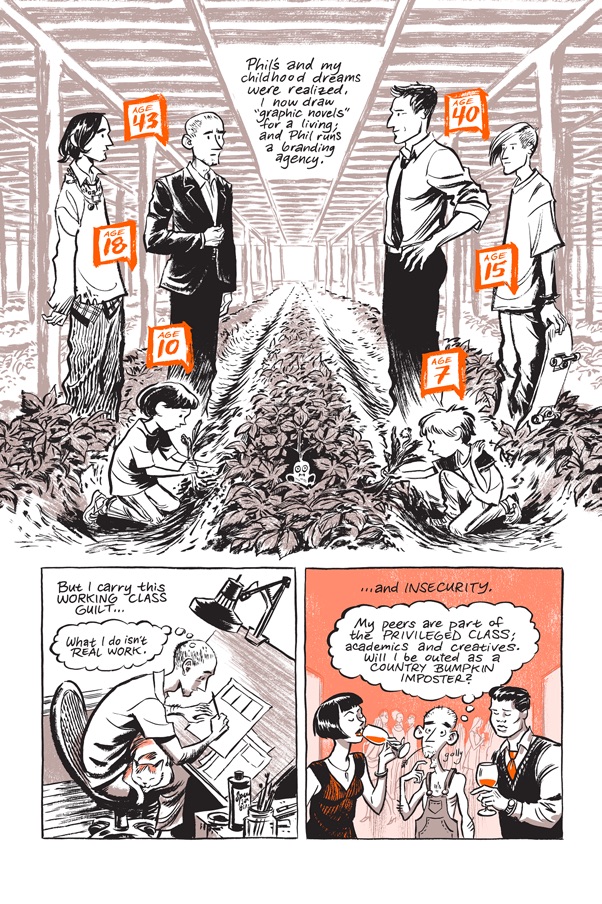

Ginseng Roots, his latest book, serialized in about 12 installments, the first 3 of which are currently available from Uncivilized Books, chronicles his experiences as a child harvesting ginseng with his family in Marathon, Wisconsin, a small town that, during the ginseng boom of the 1980’s, when the dried roots were fetching up to $65 a pound, was flourishing thanks to an influx of cash from buyers in Taiwan, Singapore, Thailand, Hong Kong and China. Thompson began working in the ginseng fields, weeding around the valuable roots, when he and his sister and brother were 9, 8 and 6 respectively (The author made a creative decision to omit his sister from Blankets, but she appears as an ancillary character in Ginseng Roots.) In need of supplementary income, their parents put all three children to work during the Summer at an age when most children are attending camp or simply lying around all day. In scenes set in the present day, the siblings candidly share their thoughts and feelings of deprivation and resentment, while acknowledging the complexity of their childhood situation.

These personal reflections are interwoven with strands of graphic journalism. In interviews with local farmers, most of whom were terribly strained when the industry crashed in the early 2000’s, the artist gives us a look at the history and practice of ginseng cultivation in Wisconsin, a fascinating and sobering window into the American agriculture industry writ large.

These personal reflections are interwoven with strands of graphic journalism. In interviews with local farmers, most of whom were terribly strained when the industry crashed in the early 2000’s, the artist gives us a look at the history and practice of ginseng cultivation in Wisconsin, a fascinating and sobering window into the American agriculture industry writ large.

But Thompson isn’t content to stop there. A third thread in the book presents us with an anthropomorphized talking ginseng root, called Ginseng Boy, who purports to teach the reader about Chinese language and mythology as it relates to ginseng cultivation. These interludes are intended to bring some levity to what is otherwise quite a serious and compelling investigation of place, class, upbringing, religious belief, factory farming and global capitalism, but they strike a false note, and I found myself wondering what age group the work is intended to reach, and why Thompson is doubling down on Orientalist material after the disastrous results of his sophomore novel, Habibi. I suspect the answer to the latter question has something to do with ambition; the ambition to please parents who can’t understand one’s artistic vocation, and the ambition to tell a story larger than oneself, a story with broad appeal, a story, even, that could create a deeper level of understanding between people of different backgrounds, a story that could bridge gaps and heal old wounds. In the first issue of the new series, Thompson cites Gabrielle Bell as an inspiration for his return to memoir.

A funny alchemy, though, happens when you write memoir. Counter-intuitively, the work that is most personal, most intimate and most specific to one’s own experience tends to be the most relatable to others and have the broadest appeal. The contemporary masters of the genre: Bell, Lynda Barry, Rina Ayuyang, Sacha Mardou, Laura Park, Lauren Weinstein, Bianca Xunise, Keiler Roberts et al… all tell small, intimate stories that provide us with insight into their upbringings, longings, frustrations and triumphs. Each one of these small stories tell a larger story: human beings are infinitely complex, but our needs and desires are profoundly similar across cultures and religious backgrounds.

A funny alchemy, though, happens when you write memoir. Counter-intuitively, the work that is most personal, most intimate and most specific to one’s own experience tends to be the most relatable to others and have the broadest appeal. The contemporary masters of the genre: Bell, Lynda Barry, Rina Ayuyang, Sacha Mardou, Laura Park, Lauren Weinstein, Bianca Xunise, Keiler Roberts et al… all tell small, intimate stories that provide us with insight into their upbringings, longings, frustrations and triumphs. Each one of these small stories tell a larger story: human beings are infinitely complex, but our needs and desires are profoundly similar across cultures and religious backgrounds.

Thompson is a deeply ambitious man, and though his ambition is what lifted him out of a life of small-town poverty, it’s also a source of pain. He touches on this briefly in the first issue of Ginseng Roots. Since the release of Habibi and his subsequent YA series Space Dumplins, the artist has been living in L.A, trying to negotiate film deals but feeling frustrated, isolated and uninspired. Justifying his decision to serialize this current work in the “letters” section of the first volume, he expresses some ideas very similar to Alexander Dunst in his ridiculous recent Jacobin article Graphic Novels are Comic Books, But Gentrified. Thompson derides the supposed pretension of the form, and expresses a desire to return to the humble roots of the medium, which give a measure of freedom that a book-length work doesn’t allow. Cartooning is lonely work, and the sheer amount of physical labor required to produce a graphic novel is staggering. It can be difficult to get any critical distance from a work into which you’ve invested so much of your time, energy and hope for the future.

Although I profoundly disagree that the graphic novel is a pretentious (or gentrified!) art form, I applaud and deeply empathize with Thompson’s desire to open up a line of communication with his audience, because I think that’s where he went so wrong with Habibi, a 600+ page fantasy epic set in the imaginary Muslim kingdom of Wanatolia, the myriad problems with which are excellently articulated by Robyn Creswell in his New York Times review The Graphic Novel as Orientalist Mashup. According to Edward Said in his landmark 1975 book, Orientalism is simply “the discipline by which the Orient was (and is) approached systematically as a topic of learning, discovery and practice.” The problem is that in viewing the East as a distant land full of mysterious knowledge to be gathered, interpreted by the scholar or amateur enthusiast and then shared with the Western reader in easily digestible fragments, the Orientalist de-contextualizes and decomplexifies their material. The antidote, Said suggests, is “to reflexively submit one’s method to critical scrutiny.”

Although I profoundly disagree that the graphic novel is a pretentious (or gentrified!) art form, I applaud and deeply empathize with Thompson’s desire to open up a line of communication with his audience, because I think that’s where he went so wrong with Habibi, a 600+ page fantasy epic set in the imaginary Muslim kingdom of Wanatolia, the myriad problems with which are excellently articulated by Robyn Creswell in his New York Times review The Graphic Novel as Orientalist Mashup. According to Edward Said in his landmark 1975 book, Orientalism is simply “the discipline by which the Orient was (and is) approached systematically as a topic of learning, discovery and practice.” The problem is that in viewing the East as a distant land full of mysterious knowledge to be gathered, interpreted by the scholar or amateur enthusiast and then shared with the Western reader in easily digestible fragments, the Orientalist de-contextualizes and decomplexifies their material. The antidote, Said suggests, is “to reflexively submit one’s method to critical scrutiny.”

By serializing this work, and by inviting letters from readers, Thompson has opened himself to such scrutiny, and I hope that others will weigh in with their thoughts and opinions on all of the topics that Ginseng Roots brings to light. That said, Said makes clear in his book that he in no way believes scholars should be limited to only representing people from their own backgrounds. Thompson mentions a trip to China, and I’m curious to see how he handles that material in subsequent installments of the series. All in all, Ginseng Roots, though uneven and problematic in the ways that I’ve mentioned, represents a significant leap forward from Habibi (I have not read Space Dumplins). I hope that Thompson will take some feedback to heart, and that he comes to recognize that his own experiences, and those of the farmers of Marathon (and potentially towns in rural China), illustrated with his considerable skill and enthusiasm, are more than enough to sustain prolonged interest.