Let me just say upfront that the production values in the now-complete three-volume biography of the cartoonist Alexander Toth are beyond reproach. Visually, the just-released third and final book, Genius, Animated, compares favorably to IDW's other collections that I own and admire regularly, such as their exemplary Milton Caniff collections. One can quibble with the editors' selections and the books' design and I will----but all of the art is shown in a generously proportioned format and the printing is very sharp and clear.

But for a series that claims to be the definitive statement on Toth, it falls short, because the text does not do justice to its subject. As biography, the account it presents feels skewed against the artist. Further, because of the books' tendency to highlight the least interesting and most conservative aspects of what he did while ignoring or misunderstanding or failing to communicate in any meaningful way what makes Toth's work so exciting and innovative, what is established is that Toth was a contentious man who became a particularly boring and cranky old fart.

There are only twenty pages of text in Genius, Animated, oddly strewn throughout the book, and unfortunately, their content is very thin. The book borrows nearly all of its Toth quotes from Darrell McNeil's suppressed 1996 Toth animation model sheet and storyboard collection, By Design, but without properly citing McNeil. The present volume also pulls quotes from the autobiography of Toth's boss, the animator Iwao Takamoto---but it doesn't qualify Takamoto's critical remarks about Toth with the information that Takamoto had run afoul of the sensitive artist by removing Toth's signature from his model sheets. This and other telling information about Toth's animation career can be found in Alter Ego #63 and Comic Book Artist #11.

Those two special Toth issues of TwoMorrows magazines contain numerous interviews conducted by comics historian Jim Amash with artists involved in the animation and comics industries who knew Toth---interviews that Mullaney and Canwell liberally appropriated passages from for their two previous volumes of the Genius books without offering sufficient acknowledgement. Amash was not thrilled. But for whatever reason, in Genius, Animated the bulk of testimony comes from original interviews conducted with three animators. Floyd Norman offers interesting anecdotes about working with Toth, but Robert Alvarez and Mike Kazaleh apparently didn't have any direct interaction with him. Half of the first two-page chapter of Genius, Animated is comprised of Alvarez's stories of dumpster-diving behind the Hanna-Barbara studios when he was a kid (but not actually finding any Toth art) and reading DC comics (again, not by Toth). Alvarez did eventually work for H-B and utilize Toth's model sheets, but his main function here seems to be to explain why he and his fellow animators didn't take advantage of Toth's elaborate fencing diagrams for The Three Musketeers segments of the cartoon variety show The Banana Splits.

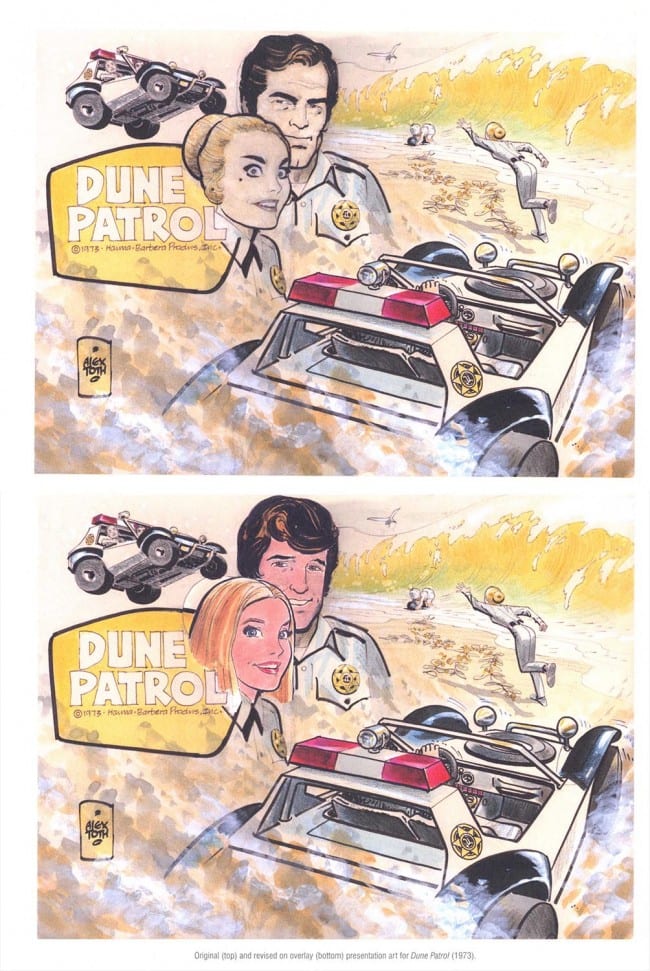

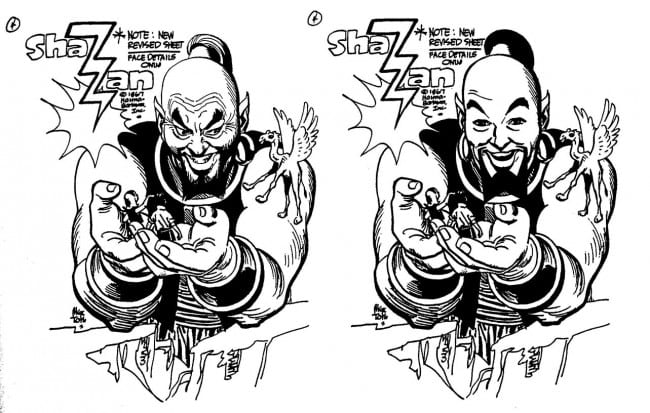

The cartoons Toth was involved with were not good, though the artist cannot be blamed for that. Even if the productions had followed Toth's designs explicitly (they didn't), the shows are conceptually and aesthetically weak. But the editors present them as if they are among Toth's highest achievements—though Canwell seems to rival the reactionary bent of his subject when he writes that The Banana Splits was meant to reflect for kids "the 'peace, love, dove' sensibility of the late '60s," as if imparting non-violent values to children is something that deserves ridicule. Still, Toth's model sheets and storyboards are the most memorable aspects of those cartoons and they are well represented here. In particular, a penciled storyboard for Dino-Boy, others done with ink and conté crayon for Super-Friends, and a large number of never-before-published color presentation boards are the best features of the book.

But some of the art in Genius, Animated isn't by Toth and one wonders if the authors can tell the difference. For example, pieces by other artists on pages 62, 65, 66, 118, and 255 are not credited as such and the storyboards on pages 108 and 109 are clearly by Doug Wildey. What is Toth's doing is a certain unpleasantness in some of his faces that he or other production artists subsequently altered to make the drawings usable (a mean edge can also be seen in the faces of some of Toth's early 1960s comics, even in his heroes).

Toth's most important work is his comics and those are dealt with in the two previous volumes. I reviewed the first volume Genius, Isolated harshly on the site Hooded Utilitarian; that can be found here. The second book Genius, Illustrated contains some of the artist's finest efforts, but again the text has serious deficiencies. Even the title mislabels the masterful cartoonist as an "illustrator." A cartoonist's contributions to any given story approximate what an entire film production applies to a script. In Toth's case, his brilliant skills in timing, staging, casting, acting, atmospherics, etc. are also subject to his unparalleled framing and page design sensibility. It is his talents in these areas that advanced comics as an artform and made him so influential. While of course illustration has its own virtues, it can be best described as imagery done to accompany a text that stands complete of itself. The artist only rarely took on such assignments.

Genius, Illustrated does have virtues. The large reproductions of the original art of complete stories like "Lone Hawk", "Bookworm", "Case of the Curious Classic", "Burma Sky", and the artist's previously unseen, reworked version of his DC war masterpiece "White Devil, Yellow Devil" are all fabulous. There are some very nice figure drawings done from live models and other pages here and there that I hadn't seen before, as in the section on his military work. However, I am underwhelmed to see "Tibor Miko" and the overrated "Taps" badly reproduced one more time, as well as other stories that are in Manuel Auad's Toth collections, like the Roy Crane homage "Oo La La". It would have been nice to see all of "Daddy and the Pie" or other Warren stories without the reversed captions by editor Bill Dubay that the artist hated so. Most of Toth's peak 1970s DC work is disregarded, including the House of Mystery and Witching Hour stories and the sideways-printed "Anachronism". We are given tantalizing hints, such as that Toth colored the first dozen pages of his magnum opus "Bravo for Adventure" and that he did a splash for a story about the Robert E. Howard character Solomon Kane, but where are they?

The design of the trilogy is elegant but conservative and so it does not reflect the artist's progressive design tendencies; this is most noticeable in the second volume which deals with his most advanced work. The worst omission is that there is virtually no analysis of Toth's storytelling or drawing techniques to be found in these three humungous books. The only instance is a brief description in volume 2 of a few devices Toth used in one of his final pieces for Warren, "The Reaper", that paraphrases part of my own analysis of that story. It is hard to understand why there is so little meaningful commentary. Or, why any sense of the excitement I and so many others have felt about this incredible artist's work since our childhoods is so entirely absent.

In an interview, Canwell disparages Manuel Auad's compilation of Toth's hot rod comics One for the Road as "tough sledding," but I prefer that book, as well as Greg Sadowsky's recent collection Setting the Standard for Fantagraphics and Image Comics' artist-toned Zorro reprint, because they offer complete and significant bodies of work. In the Genius trilogy, the authors offer precious little about Toth's Standard, Dell, and hot rod magazine work, or his superlative 1960s and '70s DC and Warren work. Most of the companies' personnel that were involved are dead and so perhaps there is no one to speak of how it came about, but regardless, his comics work for various companies is sluffed over or even disparaged in an absurdly perfunctory manner. Oh, the late Joe Kubert is given space to unconvincingly defend his philistine overreaction to Toth's alterations on the lost Enemy Ace story, but why? Apparently, just to emphasize what a dickhead Toth was.

A distinct prejudice of the authors against the artist is exposed in the form of their assumption that Toth's alterations to scripts were nothing but presumptuous and that they were always something that the writers disliked or took offense at. But contrary to Mullaney and Canwell's opinions, Toth's changes were always clearly improvements and so minimal or subtle that most often the writers either didn't notice them, or they actually figured they had written the stories that way. The overwhelming majority of writers who were blessed with Toth's art were simply thrilled to have their stories realized on such a high level—including the famously obnoxious Robert Kanigher, who wasn't foolish enough to complain when Toth made his stories function more elegantly (and it should be noted that Toth could only change the text of a script if he was also the letterer, which happened rarely).

As the books shamble towards the artist's late career and death, the patronizing tone of the text and the aura of schmaltz become nearly unbearable. I won't pretend Toth wasn't difficult, but throughout the series, the opinions given are predominantly those of people he had problems with—and those accounts and the descriptions of his mental and physical health entirely eclipse any discussion of the significance of his work. Many people retire around the time that Toth stopped producing regularly and they are not castigated for it—and his health held up until he was quite elderly. The contributions and opinions of David Cook and other friends who Toth corresponded closely with in later years are conspicuous by their absence. Perhaps they might have conflicted with the overwhelmingly negative picture that the authors paint of the artist.

Finally, while it is hard to argue against the involvement of Toth's family, it exacerbates a sentimental approach. I understand that his family had to deal with a challenging individual, but at the same time, an artist's family are not always effective advocates for the work. I do believe that they should receive whatever benefits there are of his legacy, but in most of Toth's work, there are no royalties to be had, almost everything he did was work-for-hire. Anyway, with art books, the spoils go to the authors. Including, I would imagine, the profits from these three expensive and pretty, but in the end, depressing tomes.