I will begin by confessing that I've never found Jim Woodring's comics to be particularly elusive, which is perhaps different than declaring them surreal. The latter appellation, of course, is understandable; since the advent of Jim, those many years ago, Woodring's works have been inescapably associated with the dreamtime state – that unique fusion of waking and sleeping autobiography that was the corpus, in relevant part, of his gift to the American funnybook memoir. And, in approaching that most neurotic, observational, plainspoken method of comic-book storytelling -- the verbatim legacy of Justin Green, of Harvey Pekar -- and polluting its depictions with a full range of subconscious potentials, well: you might call that classically Surreal.

But I think less of specialized terminology when I sit down with Woodring than I do of remarks he made to Gary Groth almost twenty years ago: “I believe in a collective unconscious and I believe that we are all connected mentally on some level — psychically or otherwise.” My mother's aunt, when I was a child, was an avid newspaper comic strip reader, going back to the Katzenjammer Kids in the gray days of Depression; it was she who bought me my first Mickey Mouse comics, and while I can't say our tastes aligned very much after that, I can vividly recall a sudden moment of connection between us, on the occasion of the release of The Frank Book in 2003:

“I like this,” she said. “This guy is really good.”

The truth is, all you really need to understand the Frank comics -- those wordless exploits of a quintessential Funny Animal Character set loose in a “closed system of moral algebra,” per his creator -- is to understand virtually anything of our long, shared cultural history of Silly Symphonies and Looney Tunes. And if Frank is not so cuddly as the rest of the menagerie (though still cuddlier than some), it's because Woodring is less interested in replicating popular cartoon formulae than in distilling the fraught concept of “antics” itself into a sort of linguistics – observing, again, a reality of intuition.

Lately, Woodring has been concerned with what the book dealers call graphic novels, and it was to my delight that these latter works did not come across simply as longer Frank stories between hard covers, but rather as works of mythopoeic sweep, in ready dialogue with one another. In 2010's Weathercraft, Woodring revised one of his crueler gag shorts (1996's “Gentlemanhog”) into a study of cyclical mechanisms, in which a corpulent, ignorant humanoid beast becomes an enlightened and empathetic individual, only to find himself reduced again to a bestial state as the story concludes with everything reset for further exploitation later on. Frank is just a supporting character, “adopting the attitude that will bring him the most fun,” and occupying the book's final panel by sitting down to peruse a magazine, as if eager to get the next story started.

That subsequent tale was 2011's Congress of the Animals, which differed wildly. Its early scenes remain Woodring's bluntest work of societal allegory, seeing the earth itself foreclose on Frank's house and forcing the fuzzy lil' fuck into getting a job. This leads to a quest of Frank's own -- at one point, he literally draws a sword to slay a dragon -- at the close of which he is rewarded, justly, with the companionship of Fran, a fair maiden who returns with him to his restored home. How do we know they're meant for each other? Why, they sort of look like the same creature, of course, and funny animal cartoons have long resisted the hint of miscegenation by pairing boy mice with girl mice, girl cats with boy cats, and... Frank with Fran.

I did not consider, at the time, the implications of such a pairing – the terrifying inevitability. Nor, when Woodring revealed She-Frank's true name, did I notice the metaphor behind arriving at a “woman” (to the extent these characters suggest gender attributes), by subtracting something from a man, like Eve from Adam's rib. I was simply happy, having read of Frank's escapades for so many years, that he seemed to have done well for himself, and moreover that Jim Woodring had answered the fatalism of Weathercraft with a paean to successful evolution.

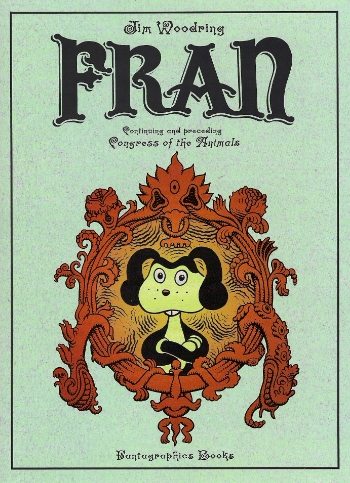

This, you are noticing, is a classic patriarchal narrative. The hero, the MAN, in all his Campbellian splendor, seizes his Boon, the maid, and crosses the threshold improved. Ideally, this would not be the end of the conversation, but the beginning, and so we have Woodring's spanking-new Fran, named for "the girl" herself.

Quickly, you realize this is not actually the story of Fran, the character, but a story about her, inseparable from the perspective of Frank, whom we come to realize is a bit more invested in this relationship than is Fran herself. I mean, heck – we're already making gendered assumptions based on the feminine curves of someone's floppy ears (linguistics, remember), so we might as well acknowledge that the concept of monogamy might well be foreign to Fran, who is reluctant to share details of her past with Frank, precipitating a blowout row. She leaves him, immediately, and Frank must once again embark on a journey to try and win her back, though the concept of "winning," now, is burdened with the possibility that Our Hero has made the critical mistake of selecting for his mate an entity that not merely looks like him, but is as fundamentally capricious as well.

This realization is the heart of this book. Back in Congress of the Animals -- which only promised “[c]ongress” among animals, remember, not lasting peace -- Frank discovered his love in a house that looked like him. Always, she flattered his self-image, a derivation from Fran[k]. Following such mythic predecessors, it seems silly to compare Fran to a popular romantic comedy like (500) Days of Summer, but much in the way that 2009 blockbuster called into question the narrative certainties of its genre by positioning one of its central pairing as only partially knowable, and the other as unreasonably assured of his place in the story, Woodring disrupts the "conclusion" of his own prior book by forcing us to consider that Frank's point of view might only allow for the possibility that he is the protagonist of every situation in which he finds himself.

In other words, if Congress of the Animals sought to set Frank free of the circularity of his narrative space, Fran is arguably more ambitious: it seeks to examine the very presumptions that follow the idea of a "protagonist" in a "narrative," understanding that elevating a hero diminishes the perspectives of those he encounters.

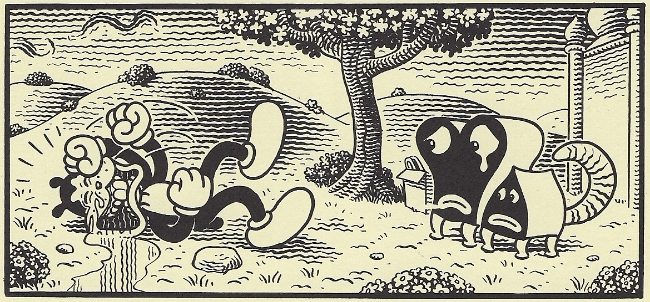

Fran, we learn, is something of a shape-shifter; sometimes she has three arms, and sometimes she is standing in two places at once. This may be Woodring's way of communicating movement, of animation, but the very fact that Fran moves in a different way than Frank suggests that even her appearance as a female version of him may be an illusion, built up from Frank's own desire for a partner. By the time Frank pursues her to the other side of the country, Annie Hall-style -- where she's shacked up with some sandals 'n' skirt-wearing hippie who responds to Frank's awesome, frothing-at-the-mouth anger with hugs and grins -- her body has become bulbous and strange, his idealization of her breaking down. He is terrified by her independence, at the notion that she has an existence, a form, outside of him; that she had a life before, and will, presumably, thereafter.

It was at that point in the book when I realized that Woodring was implicating his very approach to comics. Collective unconscious, after all, can easily manifest as shared delusion, and few are more pernicious and cartoon-ready than the Happily Ever After. Fortunately, Woodring is so keyed in to the source of all of this, that he is prepared to posit the recurrence of stories again and again throughout funny animal history as less the hell of Weathercraft, now, than as a means of challenging the pat conclusions of these cultural myths.

All things must pass, Fran says. In the event you don't see some time in your life where a lover no longer feels for you in the way you'd like, rest assured that you will know their death, or they yours. And in a hundred and fifty years, your family, your children -- everybody who loved and understood you in an immediate manner -- will be gone from this world, and whatever impact you had mustered from your time as a living thing will be most likely forgotten, if not left in some state of depreciation. And life and stories, of course, will continue, the big wheel turning.

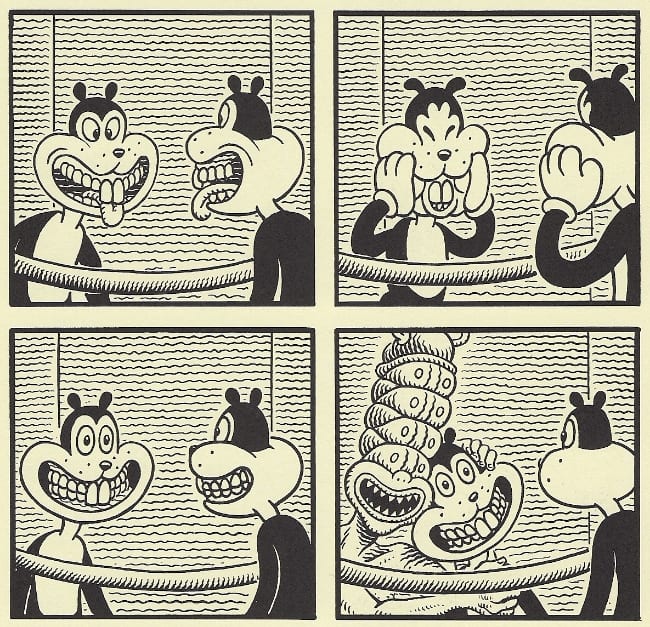

None of this is to suggest that Woodring is against the possibility of growth, or education. There is a marvelous scene toward the end of this book where Frank finds himself inside a curious museum. It is the first time in a while where he is seen laughing at the many fun exhibits. Then, he approaches a roped-off portal, which seems to function as a mirror. He makes silly faces, and enjoys himself greatly, until he suddenly has a vision of Fran's weird hippie boyfriend grinning alongside him, and he is terrified once again.

This neatly summarizes the themes Woodring has been building, of Frank as a subjective perspective, navigating a world according to him. But also, it is allegorical on a wiser and more emotive level, insofar that relationships with people leave parts of them inside us. To see an old lover, an ex-spouse, with someone else, is to witness a crucial aspect of the self become displaced, so that this new lover, this new spouse, is somehow involved with you. It is solipsistic, yes, but I suspect more natural than we'd care to admit, so trapped in here behind our own eyes.

And should Frank sit down with another book, as he did at the end of Weathercraft, we will know it is not the end of anything, really, but merely a recurrence. Hardly the end of the world, because even if the world and memories and stories possess some ultimate form, they can only be understood by individual humans with unique and valid and true desires. Will Frank retain this lesson? Maybe not. But will we?