Religious communities are complex enclaves, and they operate under their own logic, which can sometimes runs counter to that of other, secular communities. The insular nature of the communities and the peculiarity of their workings often make them inaccessible to most outsiders. I was never a part of these communities, but growing up in and around North Dallas suburbs, which includes the ultra-Christian city of McKinney, I interacted with them and their members frequently. Community members’ entire lives are organized around their relationship to their church and other congregates—often determining where people go to school, where they live, where they work, and how they raise their kids. But these organizing principles don’t merely prescribe beliefs, they prescribe practices. These communities concern themselves more with what you say, do, who you vote for, and who you associate with than with what you believe or profess to believe. Because of this, they function more like a political identity than a religious identity, and they cannot be analyzed on their competence in adhering to religious belief. You have to observe what they do and not what they say. This is something that L. Nichols renders with a keen eye in his most recent book, Flocks.

A memoir, Flocks emphasizes Nichols’ relationships with various flocks—communities of people that share some moral scheme and attempt to impose it on even the most reluctant of members. These include the religious communities of his youth, the secular communities of his college years, and the queer communities that he moves in and out of throughout his life. Nichols is a trans man assigned female at birth—a fact that motivates a lot of the tension in his life. At first, he is confused about his sexuality, attracted, as he is, to both men and women. He isn’t sure what to make of these desires—where they come from or what to do about them. For a time, he believes himself to be a lesbian, which causes some internal friction when his desire and the moral beliefs he has been inculcated into are at odds. This friction is exacerbated by his fellow congregates’ stances on homosexuality, and ultimately his religious community ends up causing him a great deal of turmoil. This turmoil is quelled somewhat by the community he finds at M.I.T., but those communities come with baggage of their own, moral prescriptions of their own. Nichols seeks some resolution in these seemingly-open secular communities, but they cannot give him the answers he longs for. This results in an inward turn, a search for the problematic kernel within himself that he can excise and feel better. This takes the form of periods of deep depression, of self-medication and self-harm. By the book’s end, however, Nichols has come to understand himself better and his conclusion to this story gestures towards a happier, more fruitful future.

But Flocks is moving not because it serves as a bromide against religion and religious communities—it is moving precisely because it resists that impulse. While Nichols is not shy about rendering all the pain elicited by these flocks, he does not reduce their existence to this pain and this pain only. They can cause great suffering, but Nichols also finds incredible joy in religious practice. As a child, Nichols revels in the beauty of participating in his church choir; the sense of belonging and the overwhelming feeling of being connected to something greater than himself fills him with great pleasure. This is the same pleasure he finds in nature—exploring, investigating, and entangling oneself in the works of God. This is the obverse of the coin of religion, the great pleasure that emerges from a belief that you are loved: deeply and unconditionally.

But Flocks is moving not because it serves as a bromide against religion and religious communities—it is moving precisely because it resists that impulse. While Nichols is not shy about rendering all the pain elicited by these flocks, he does not reduce their existence to this pain and this pain only. They can cause great suffering, but Nichols also finds incredible joy in religious practice. As a child, Nichols revels in the beauty of participating in his church choir; the sense of belonging and the overwhelming feeling of being connected to something greater than himself fills him with great pleasure. This is the same pleasure he finds in nature—exploring, investigating, and entangling oneself in the works of God. This is the obverse of the coin of religion, the great pleasure that emerges from a belief that you are loved: deeply and unconditionally.

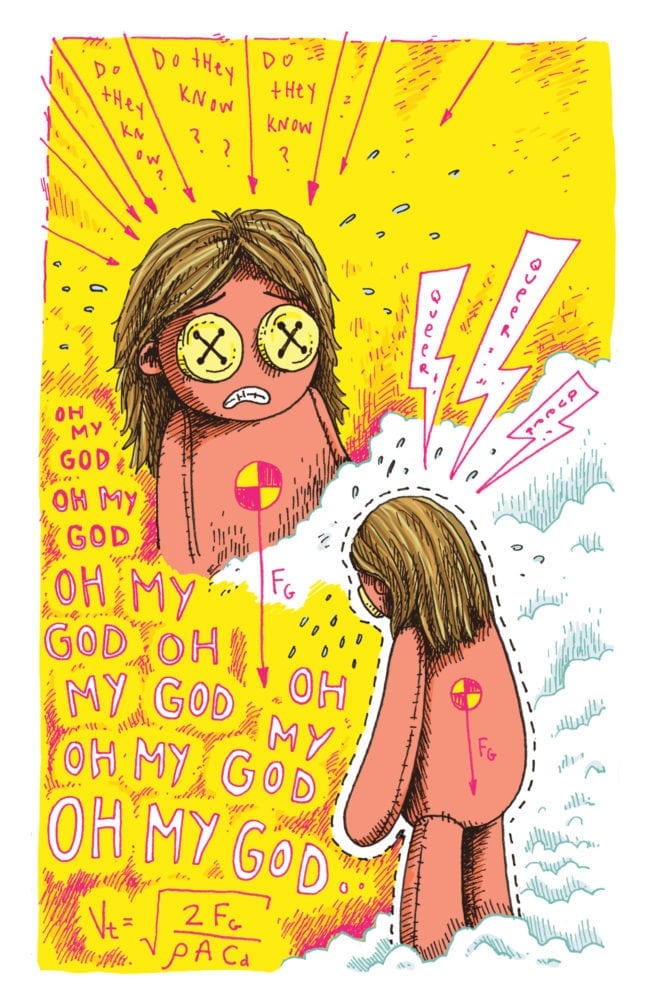

The way that Nichols visually renders these pleasures is similarly worth noting. Throughout the book, Nichols signals emotional states by drawing arrows towards himself. These arrows sometimes take the form of lightning bolts, scraggly and castigating lines, or straight lines annotated with mathematical formulae. Whenever he is made to feel bad, insulted, or harassed, he represents this by drawing a line—literally—from the elicitor to himself, as if to say that these figures are pushing in on him, enforcing themselves on him. The lines coming at him are signs of oppression and hate. He reverses this to represent the love he feels in communion with God, rendering those scenes with a halo of lines emanating outward, emerging from within himself. This is part and parcel of Nichols’ broader aesthetic, which merges expressionistic portraiture with elements of naturalistic cartooning. The world is, by and large, rendered realistically so that it resembles the world and the people resemble people. Nichols renders himself, however, as a doll—alternately resembling a ragdoll and a crash-test dummy. This method of portraiture makes Nichols’ self-image infinitely pliable, and, I imagine, less emotionally taxing for him to manipulate. We see his body altered—in some cases, expressionistically disfigured; in some cases, literally disfigured—and Nichols can be explicit without being graphic. He can affect us deeply without it repelling us with viscera. The story is a deeply emotional one—that is, it is about emotions, emotional turmoil and distress—and Nichols affectively renders that core thematic visually. He makes it felt in not just what he draws but also in the way he draws it.

Ultimately, Flocks is a compelling book for two reasons. The first is the sincerity with which Nichols writes. The self-as-doll aesthetic offers him a slight distance between himself and his story, but that distance is not that of an ironic detachment. He does not push the story or its emotional heft away from himself or from us; rather, he makes it easier for him to tell and easier for us to listen. This kind of sincerity is emotionally laborious to produce, and Nichols should be admired for this fact alone. The second noteworthy feature of Flocks is the seriousness with which Nichols’ treats his religious subjects. Rather than reducing these communities to caricatures or one-dimensional pits of hatred, Nichols explores the complexity of them. They continue to hold so much sway over American life because there is something appealing about them. They speak to some desire, some need to feel connected, some great longing for love that motivates all human activity. Nichols successfully treats them in all their failings and all their glory, all their hatred and all of their love. He shows how similar they are to secular communities, how multifaceted they are, and how much they continue to offer the individual in periods of confusion, tension, and hopelessness. Flocks is a work of love—a work about love, a work made with love, a work made to express and communicate a love. For all its idiosyncrasies and imperfections, it is a work to be held close to your heart, a work to be cherished.

Ultimately, Flocks is a compelling book for two reasons. The first is the sincerity with which Nichols writes. The self-as-doll aesthetic offers him a slight distance between himself and his story, but that distance is not that of an ironic detachment. He does not push the story or its emotional heft away from himself or from us; rather, he makes it easier for him to tell and easier for us to listen. This kind of sincerity is emotionally laborious to produce, and Nichols should be admired for this fact alone. The second noteworthy feature of Flocks is the seriousness with which Nichols’ treats his religious subjects. Rather than reducing these communities to caricatures or one-dimensional pits of hatred, Nichols explores the complexity of them. They continue to hold so much sway over American life because there is something appealing about them. They speak to some desire, some need to feel connected, some great longing for love that motivates all human activity. Nichols successfully treats them in all their failings and all their glory, all their hatred and all of their love. He shows how similar they are to secular communities, how multifaceted they are, and how much they continue to offer the individual in periods of confusion, tension, and hopelessness. Flocks is a work of love—a work about love, a work made with love, a work made to express and communicate a love. For all its idiosyncrasies and imperfections, it is a work to be held close to your heart, a work to be cherished.