Leslie Stein's fastidious, beautiful line continues to be put to good use in the second volume of her loosely connected semi-autobiographical stories, Eye Of The Majestic Creature. Indeed, this book is simply a collection of individual issues, though many of them were never actually published prior to this book. Stein works best in a short-story rhythm, and the covers and other artwork for individual issues work nicely as natural stopping points. For a work of magical realist autobiographical comics, having that kind of break makes sense for the reader. However, there are themes and through-lines in the book that make this collection a surprisingly coherent single package, documenting Stein's restlessness and search for identity.

The first story picks up where the last book left off. The book is still about the life of Stein's surrogate Larrybear, working as a shopgirl in New York City, living in a roach-infested apartment and spending time with her anthropomorphic musical instruments. What's different is that the first story's narrative captions are all taken from Theodore Drieser's 1900 novel Sister Carrie. The only real similarity between the two works is that both concern a young woman trying to make it alone in a big city, but the circumstances surrounding the protagonists of those works are quite different. Everything about this issue is dialed down from previous volume: emotions are more restrained, the magical realist aspects of the story are far more matter-of-fact, and the entire story takes on a more plaintive, solemn tone. This is true of the rest of the book as well, which doesn't have quite the sense of loony joy or bar-hopping shenanigans of the first volume.

The connections that Stein makes between Dreiser and her own story are fascinating, especially when Dreiser starts talking about the bustle of city streets, the loneliness of city life, and the divide between the haves and the have-nots. Larrybear is a person adrift, desperately searching for an activity to give meaning to her daily hustle and bustle. She finds it in the art of "sand counting", a hilarious metaphor for any obsessive, time-consuming hobby that can be considered art--like comics. In many respects, this single issue is a recapitulation of the entire series to date, only done from a different angle. Instead of being dominated by Larrybear's interior monologue, we instead get Stein selecting Dreiser quotes to comment on her life. The comic is faster-paced than the more languid and tangent-filled stories of earlier issues, with days and weeks going by as Larrybear goes through winter and into the first glimpses of spring. Stein here is measuring the weight of days and weeks on her stand-in, the debilitating passage of time in a life desperately spent looking for meaning and purpose. Larrybear manages to find that balance, to find a way to survive and thrive in the big, impersonal city, even as she comes to terms with the way she's becoming more removed from her anthropomorphic friends. Those friends are symbols of her imagination but also a symbol for abandoning music in favor of a different pursuit, one that's far more solitary.

The next section features a trio of stories drawn from Stein's childhood. The first is a restrained and fascinating story told from the perspective of her mother about going to Disney World with her brother and mom. Her mother, who was divorced (but had a boyfriend) wound up taking a guy she met at a club along with them. Stein's understated storytelling gets at the heart of the weirdness of the situation, as this guy essentially functions as a surrogate father on a temporary basis, one of many she no doubt encountered throughout her childhood. That's heightened by the weird reality of vacation time, especially in a place as overwhelming and unreal as Disney World. The final image, of the man watching cartoons with them as their mom sleeps, underscores the ways in which children adapt to changes in routine when routine no longer exists.

That theme is further emphasized in "Brown Heart", which is about young Larry accompanying her mother to her AA meetings (it's not until later in the book that Stein reveals that her mom's addiction was to painkillers, and that made her sleep all the time). Stein keeps the reader in the dark as to where she's going with her mother, with the emphasis early in the story finding a way to keep Larry occupied during the meeting. It's not until the familiar AA drill starts and a man starts talking about his troubles that it becomes clear just how weird and inappropriate it is for her to be there, yet Larry is entirely unperturbed by attending. It's just a thing she does with her mother. What does clearly bother her is the testimony of a man who talks about his relationship problems in the context of not wanting any kids because he hates being around them. Larry draws a picture of him, winds up giving it to him, and she gets a bizarre trinket in return: a brown heart necklace. Unsurprisingly, the ugliness of the object is what concerns her the most, which again is not unusual for a pragmatically-minded child.

The other two stories in this section are also about Larry's childhood; in one, she buys a much-desired gumball machine, only to find out that her annoying cousin has eaten all of them. Again, the story is about the ways in which pragmatic matters outweigh familial concerns. The next is about a bizarre concert 13-year-old Larry plays at in support of mental health issues, one she participates in reluctantly. Hilariously, the name of her group is "Lithium". That memory flows directly from the gumball memory in terms of panel-to-panel continuity, and then flows into a coda regarding the Disney World story, where they return to her mom's boyfriend's house after the trip, where Larry casually mentions "Jonathan" (the man they stayed with) liking her jokes. It's an off-handed and even innocent comment, but one gets the sense that even at a young age, Larry/Stein knew more about what was going on than it might have seemed on the surface.

After that lengthy foray into the past, Stein returns to the present with another trio of stories. The first involves a dream about her best friend and drunkenness, which is a constant thread in Stein's comics --be it Larry's own drinking, going to AA meetings, having epic adventures in bars, etc. While never directly addressed, one gets the sense that this is a way for Stein to navigate the tension that dominated the first volume of this series: the ache of being a misanthrope who nonetheless craves being around others. Upon being told that a story she had heard about a man's memoir involved his Irish Catholic alcoholic father, her friend replies "Jesus Christ, why not write a book about a bowl of fucking soup!"

Thus, the next story is called "Soup", which is about Larry visiting Long Island with her boyfriend Poppin (drawn as an anthropomorphic flower with stubble) to visit his alcoholic father. Recovering from surgery and in a wheelchair, he's precisely the kind of belligerent, needy and soppily sentimental figure you would imagine. Poppin recounts insane stories about his father and Stein brings the story around to recounting stories of going to children's AA groups. Stein gets passed-out drunk and there's an amazing sequence where she uses silent panels to relate just how she wound up meeting Poppin, how he hooked her up with her band, and how she wound up in Long Island. It's an eighteen-panel grid (3x6) that spotlights what she does best: using a strong but fluid line, creating detailed backgrounds with her exacting stippling style, using strong images to tell a story, and mixing realism with rubbery expressionism and cartoony art.

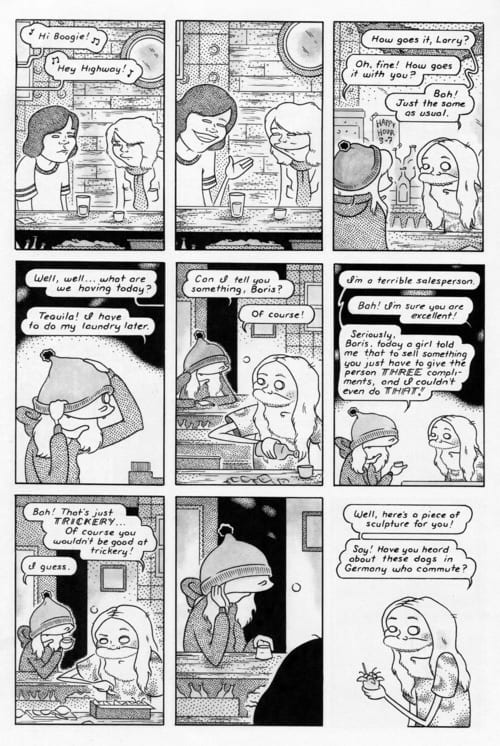

Stein ends this volume by exploring identity and asking the question that's dogged her throughout the series: "Who are you?" Playing with a Devo-inspired Booji Boy mask that gets at the heart of this idea, she quits her shopgirl job because she can't bring herself to lie in giving a customer three compliments in order to get them to buy something, which is the industry standard. This leaves her at loose ends as the book concludes, finishing a cycle of development. If the first volume of the series was about Larry's struggle to connect with others, then the second volume is about the way the lack of structure in her life as a child has affected her as an adult in terms of trying to figure out her life. The end of the book finds her no closer to an answer than the beginning, but there are hints of finding fulfillment as an artist and casting aside careers that make her feel openly deceitful. That push-and-pull is reflected in her art, which has that wonderfully quirky line and character design embedded in pages that are dense and richly packed with detail. Stein's storytelling innovations in this book point to her becoming a truly significant and mature artist as she continues to evolve in daring ways.