We’ve had almost 30 years of Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie reprinted. It remains Gray’s masterwork, but it wasn’t his sole comic strip. Though it also began with “Little” and had a red-headed child protagonist, Little Joe, which came to bear Gray’s creative stamp, has equal similarities and discrepancies to its more famous relative.

Little Joe’s backstory is fascinating. As related by Jeet Heer in one of three essays that precede the strips, it was born of spite. Gray and fellow Chicago Tribune cartoonist Chester Gould both resented Norman Marsh for his bald-faced imitation of Gould’s Dick Tracy in the strip Dan Dunn, which ran from 1933 to 1943 after its debut in the pioneering original comic book Detective Dan. To prevent Marsh from gaining a berth at their syndicate, Little Joe was born. To say more would spoil the reading pleasure of Heer’s superb essay.

Co-edited by Peter Maresca and Sammy Harkam (whose long untitled story in the recent Kramers Ergot seems to pay tacit tribute to Little Joe), the book selects episodes from the strip’s first decade. Begun by Gray’s assistants Bob and Ed Leffingwell, Little Joe is set in the modern Western United States—an unreal blend of frontier settings and violence and modern trappings. The latter always seem startling: you’ve read weeks of guys on horseback when suddenly there’s a portable radio or an Art Deco sedan.

The Leffingwell brothers brought an atmospheric, if slightly amateurish, look to the first years of Little Joe. A short selection of these early strips begins the book. When Ed Leffingwell died in 1936, Harold Gray co-piloted the strip with Bob Leffingham. The strip remained its “Leffingwell” signature, but Gray’s sensibility informed Little Joe for the next decade-plus.

This volume’s focus are the years 1937-1942, when the strip stressed often-dramatic continuities leavened with violent humor, cowpoke dialect and a surprising attitude towards Native Americans. The native characters may say “Ugh” and speak like a budget telegram, but they are regarded by the white and Latino characters as equals—a people of dignity and importance. The strip’s depiction of Native American culture isn’t free of condescension, as are Jimmy Thompson’s yet-unreprinted strips Indian Lore and Red Men, but there is respect and a sense of shared resources and culture that was rare for mass media of the time.

More strident to modern eyes may be “Ze Gen’ral,” a good-natured Latino rogue who is also on equal footing with the whites of Little Joe. He and another recurring character, Native American youth Little Dead-Pan, allow moments of anarchic mischief and gallows humor to flavor the strip without dirtying the hands of the main (white) figures.

Gray’s touch as author is abundant in these strips. His sometimes-strident sociopolitical views, which run rampant in Little Orphan Annie, often seem relaxed here. Gray’s favorite author Charles Dickens is praised in one episode—in a period when Dickens’ multi-layered plots inspired some of Annie’s greatest sequences. Annie’s moralizing isn’t in Little Joe’s agenda. The line between law and disorder is faint in this world.

Gray’s touch as author is abundant in these strips. His sometimes-strident sociopolitical views, which run rampant in Little Orphan Annie, often seem relaxed here. Gray’s favorite author Charles Dickens is praised in one episode—in a period when Dickens’ multi-layered plots inspired some of Annie’s greatest sequences. Annie’s moralizing isn’t in Little Joe’s agenda. The line between law and disorder is faint in this world.

The episode of July 7, 1940 epitomizes what makes this strip so different from Grey’s better-known work. As Joe calls out his benefactor, the trail-wizened cattleman Utah, on including livestock from another rancher’s herd as he rounds up his stolen animals, Utah comments: “That’s a great moral question, Joe! Ain’t got time to discuss that now! DRIVE THEM STEERS!” Utah’s answer is disarming and amusing, but it packs a punch and lingers in the reader’s mind.

In the strip for April 7, 1940, another older character robs a modern-day motorized stagecoach and then returns the money. Questioned by Utah, who is the sheriff of these parts, old Three-Card replies: “Aw, drat it all, Utah! It gits so DURN DULL ‘round here!”

In the strip for April 7, 1940, another older character robs a modern-day motorized stagecoach and then returns the money. Questioned by Utah, who is the sheriff of these parts, old Three-Card replies: “Aw, drat it all, Utah! It gits so DURN DULL ‘round here!”

The acts of violence perpetuated by Punjab and The Asp—Oliver Warbucks’ agents of mayhem in Little Orphan Annie—echo in the Western world of Joe. White-haired Utah must be reminded more than once that old-school frontier justice isn’t legal anymore. In other moments, characters are dispatched with poker-faced irony by white and Native American characters. Gray and Leffingwell’s vision of the post-Depression West is a hazardous place. Its terrain is evoked with a prickly presence, which suggests that Bob Leffingwell was responsible, in part, for the superb landscapes (rural and urban) that are a strong agent of Annie’s effect.

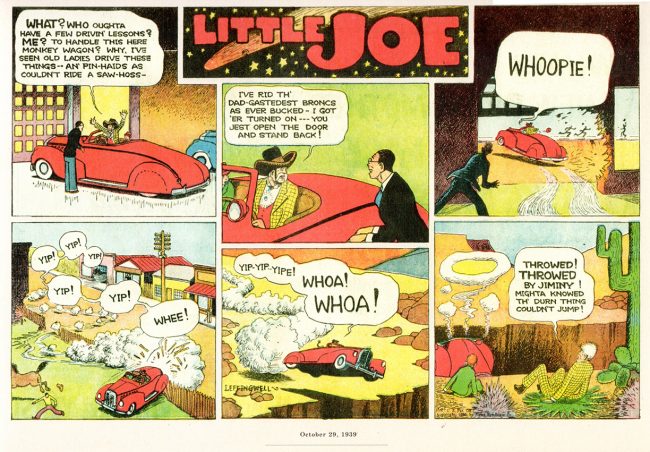

Long sequences from July 9, 1939 to January 14, 1940 and March 31st to October 30th of that year, allow an absorbing visit to Joe’s world. Tension, humor, justice and injustice, peppered with memorable visuals, classic Gray themes (a lost gold mine, which brings Joe and Utah a lot of trouble, both amusing and nightmarish) and the author’s knack for dialect make these two stretches the real meat of the book.

In both sequences, Bob Leffingwell’s skill as background artist comes to the fore. Joe’s jutting mesas, blocky boulders, rolling desert vistas and open spaces evoke a sense of being there that few comic strips bothered to create. The strips are deceptive: at six to eight panels, they seem a quick read. Their visual information rewards the reader’s prolonged gaze and creates that wistful sense of wanting to occupy this idealized, stylized landscape (but not long enough to get shot or scalped, thank you).

In both sequences, Bob Leffingwell’s skill as background artist comes to the fore. Joe’s jutting mesas, blocky boulders, rolling desert vistas and open spaces evoke a sense of being there that few comic strips bothered to create. The strips are deceptive: at six to eight panels, they seem a quick read. Their visual information rewards the reader’s prolonged gaze and creates that wistful sense of wanting to occupy this idealized, stylized landscape (but not long enough to get shot or scalped, thank you).

The half-page strip had a unique layout in its first years. A logo, always bearing a new decorative background, lodges into the top tier of panels. It forces the middle panels downward and creates L shapes for the outlying frames. Those panel shapes set a distinct rhythm to Little Joe, and the strip loses something when its format becomes more streamlined.

Gray’s zany approach to color also informs Little Joe. Those tell-tale pastel hues that render a mountainside blue in one panel, pink in the next; green, violent and goldenrod skies; walls that apparently were re-painted in-between frames—this eccentric approach seems hard-wired into Harold Gray’s psyche.

It’s terrific to see these strips reproduced so crisp and clear and at their intended size. While the ongoing Library of American Comics series of Little Orphan Annie remains a rewarding, praiseworthy effort, it’s frustrating to see the Sunday strips at reduced size. The expansive format of this book, while smaller than the average Sunday Press volume, helps bring this work to life. Like their 2015 reprinting of Garrett Price’s White Boy (another Western strip from the Chicago Tribune), it’s presented as a sort of bound portfolio, with a cloth binding that lacks a titled spine. As with White Boy, I anticipate searching in vain for this book (which is always right in front of me on a shelf) in years to come. Sunday Press’s books are a great gift to comics history and comics currency—they give their subject matter the presentation, TLC and perspective to make it engaging and compelling.

The book ends with a sequence from 1942, when the strip changes to a three-tier format and looks and feels like Little Orphan Annie. The tone is grimmer, and the final strip presented has a situation worthy of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre—described, rather than shown. It’s a hell of a way to end a book!

Little Joe continued far beyond the years covered in this book. It became one of dozens of Chicago Tribune strips that were just kinda there—never given much, if any, promotional push and used by many subscribing papers as something to fill the space when that Dreft ad fell through on the Sunday comics page. Some of these strips straggled on for decades. The Lambiek Comiclopedia website claims Little Joe ran until 1972. If so, neither the Chicago Tribune or the New York Daily News carried it to its end of days. The latest examples I’ve seen are from 1967. Still signed “LEFFINGWELL,” the strip was a poorly printed ghost of the vibrant episodes seen in this book. It’s a wonder that the strip survived Harold Gray’s death in 1968.