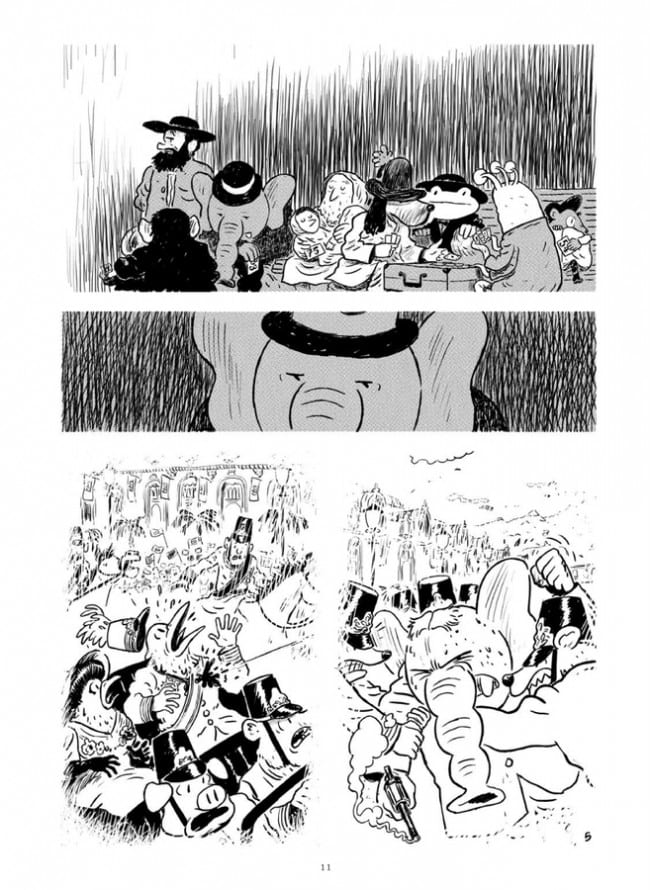

Picking up District 14, I was mildly concerned. The first couple of pages show an elephant disembarking at Ellis Island, taking a shower, and then getting ripped off by corrupt officials who want to seize his mysterious seeds. The elephant makes a break for it, fleeing directly into a crime scene where a stag-headed mobster is delivering a suitcase with a severed chicken’s head in it to a man in a black suit. Shots are fired; the elephant meets a plucky news photographer with a beaver’s head; hi-jinks ensue.

Shite, I thought. Is this going to be completely trite Euronoir like Blacksad, a pile of clichés enlivened only by the gimmick of giving stock characters animal heads?

I am not against Euronoir per se; it’s interesting to see how Europeans construct imaginary Americas. I am European myself, and find the America I live in today is rarely the one stories told me to expect. Sometimes Europeans build America very well, as in a Humanoids release from a decade ago, Miss: Better Living Through Crime. Sometimes they do it not so well, as in the aforementioned Blacksad, in which cliché is heaped upon cliché as a detective who for no good reason has a cat’s head investigates uninteresting mysteries featuring other anthropomorphic characters. There’s a very good drawing of a hand on page 15 of the first volume of Blacksad but that’s about as much good as I can say about it.

But although it does feature talking beasts, District 14 goes beyond the mere accumulation of ancient tropes and exhausted set pieces. For a start, it mixes up humans and animals. They live alongside each other in the vast location of the title, which owes something to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis in its sense of scale, but which is a little less futuristic in design. Airships drift between impossibly tall buildings, but the entrances, columns and interiors are rather French-classical. Meanwhile Gabus and Reutimann resist the urge to go for a simple metaphor with this blending of human and animal characters- there’s no (human) master race lording it over the (bestial) untermenschen here, for instance. The different species just, well, live together.

So what’s the point?

Well, I wasn’t entirely sure until I reached a marvelous sequence where the central characters visit a jungle that is growing in the upper reaches of one of the ultra-skyscrapers. Down below, naked animal-men are reverting to their original state, and lie around in a jungle, murdering people and eating their entrails. That was when I noticed that the other animal characters retain their bestial characteristics, even though they wear suits and hold down jobs: thus rhinoceros enforcers are very short-sighted, tadpole gangsters are very easy to kill, and frogs have very long tongues. There is thus a strange logic at play, almost a thought experiment: what if animals did live alongside humans in a vast metropolis? It’s hardly a question I ask myself every day, but Gabus and Reutimann do ask it, ponder the consequences, and then allow the effects to unfold within their story, thus enriching the texture of their imaginary world.

That same interest in adding disparate, contrasting story/genre elements and then allowing the consequences to develop gradually— and to modify the direction of the story— is applied throughout the book. For as District 14 progresses over its 300 or so pages, Gabus and Reutimann toss an exceedingly violent Golden Age masked crime fighter into the mix, then refugees from another galaxy, then a cat with mysterious powers— and each time their fictional universe is modified the narrative shifts. The bounds of genre are loosened and District 14 moves from straight-up noir pastiche to a complex fusion of multiple story types, in which (for instance) the rules of noir and SF and events of European history rub up against the other. Of course it’s not strange to blend genres in comics, but Gabus and Reuitmann are more varied and eclectic than most in their selection, and keeping all that material on track requires considerable skill and judgment.

My favorite element in the book is probably the riff on the popular French children’s character Babar: in his short foreword to the book Jeff Smith jokingly references Jean de Brunhoff’s books (“The authors are French after all”) but in fact, I think the “joke” is rather wry and well-worked out. It’s implied at the beginning and for most of the book that “Michael Elizondo” the elephant protagonist is an anarchist refugee who has assassinated a prince or archduke. This is a direct inversion of Babar, the wise philosopher king and architect of a pachyderm utopia, whose history of benevolent authoritarian leadership is well known to all French kids and indeed anyone who has read de Brunhoff’s magnum opus, Babar the King.

The full effect is probably lost on Anglophone readers, but I think here the same principle is in play as a Crumb or Kim Deitch telling adult stories using animal characters reminiscent of the types found in kids’ cartoons of their youth. Here however the effect is less abrasive, less willfully shocking- rather it is subtly political, even melancholy. The naïve elephant’s paradise of the kids’ stories is parodied and indeed inverted by this vast, violent, corrupt cityscape, existing on an unfathomable, impossible scale, where even an elephant is dwarfed and atomized by his surroundings: yes, children, this is the loneliness you can expect when you grow up. At the end of the book however Gabus and Reutimann surprise the reader regarding the elephant’s true identity, and the narrative starts to flow in a new direction.

District 14 then is a rather interesting and unusual exercise in ultra-eclectic world building that utilizes elements from German silent cinema, French kids’ books, noir, SF, pulp, superheroes, European history and assorted imaginary Americas. In this breadth of range the book goes further than most attempts at cross-genre fusion. Maybe only League of Extraordinary Gentleman: Century adds as many (or more) disparate elements, but Gabus and Reutimann are a lot more disciplined than Alan Moore and there is no Mary Poppins showing up to save the day in a spectacularly lazy denouement. Perhaps they had an editor who actually edited. With so many different ingredients, the book could easily have gone badly wrong both tonally and plot-wise, but Gabus and Reuitmann make it to the end without jumping any narrative sharks.

The story is baroque, filled with twists and turns, but the deeper mysteries surrounding the characters unfold at a leisurely pace. By the end of the 300 pages of “Season One” we are still a long way from reaching the conclusion, though a lot has happened in the meantime. In short, District 14 is well-written, it looks good, and it probably deserved the prize for best series it won at Angoulême last year. Perhaps my review has made it sound like an Oubapo-esque exercise in formalism, but it doesn’t read that way. Indeed, you could forget all of that cross-genre intermingling stuff and still enjoy the book as a well-executed yarn. And there’s nothing wrong with that, either.