Oh, hi there! I didn’t see you come in. My name is Tegan and I’ll be your reviewer for today. We’re going to be taking a look at Simon Hanselmann’s latest release, Crisis Zone, a massive softcover compendium of the webcomic of the same name that ran across most of 2020. The present volume was brought to us by Fantagraphics, Hanselmann’s publisher since 2014. Uhh, that reminds me, do we have to go over the conflict of interest stuff anymore? We’re owned by Fantagraphics, I’ve been a contributor to the Journal on and off since 2002. Ah jeez, I didn’t want to have this conversation today . . . at what point must we acknowledge that I have become fatally compromised? Our worst foes were right all along, I’m just a shill, a betrayer of the public trust, it’s the lowest level of the Inferno for me, snug fast alongside Brutus and Cassius with all the other comics critics at the frozen hooves of Satan . . . Personally, I wouldn’t believe a word I said. Might as well get your hard hitting industry news from Marvel Age, folks.

But, shit, we’re still here, I guess? Or at least, I hope you are. We march forward. I’m not lying in order to sell you diet pills made from shredded newspaper and pulverized bone meal so by the standards of 2021 we’re doing pretty good. You’ll excuse the long walk - I needed to stretch my legs - but that’s more or less where Crisis Zone ends up as well: any day you can keep your head above the clouds of our collective miasma is a good one, or at least better than the alternative.

Miasma, you say? Ah yes, good ol’ 2020, the year so nice we lived it twice. How else would you characterize it, if not a miasma of Oedipal proportions?

After going back and forth on the matter for a considerable amount of time I suppose there’s nothing for it but to hop right in the cold water. Simon Hanselmann is probably my favorite current cartoonist. There are a couple hedges, sure. But I’ve strained my brain for a good while and I can think of nothing in comics that makes me quite as happy as new Megg, Mogg & Owl strips. It’s been that way for me since before he signed to Fantagraphics. Always extraordinarily gratifying to see an artist you recognize as good early go on to fulfill that potential. I wish I could remember the first time I encountered the crew - was it Tumblr? It could very well have been Tumblr. I was familiar enough to be pumped at the announcement of the Fantagraphics contract, at any rate. So I didn’t “discover” Hanselmann, certainly, no more than a pico-second before anyone else did. There’s no back-patting necessary or implied here, the point is you didn’t exactly need a jeweler’s loupe to predict the future. It was clear from the moment you saw the work that it wasn’t a matter of if but when. So, look, I was joking early about the “conflict of interest” stuff, but only to hang a delicate lampshade over my real and avowed bias. I went back to check and, sure enough, I wrote about Hanselmann more than once for the AV Club - my bonafides in the matter are a matter of public record. I’m “in the tank,” as the kids say.

Crisis Zone is a beast of a book, actually hefty in the hand. Still only representative of a year’s work, total. Look at that data point, then please take a minute to flip through damn near three hundred full pages, with full-color paintings on the endsheets and flyleaf and even the goddamn back cover, to say nothing of the twelve fucking pages of cramped handwritten notes at the back of the book . . . which I read as both a fan and a critic. And, as both a fan and a critic, let me say, in the context of what I hope is recognized as generally a very laudatory review, ahem, motherfucker, I had to get out a ruler to read those minuscule notes line by line like this was grad school all over again - or worse, Sean Landers. Bitch you can’t make me read, it’s not allowed, I won’t let you. I am here precisely because I don’t want to read. We are near the same age and Hanselmann has clearly taken much better care of his eyes than I have mine, is all I have to say about that. The point? Oh yes, the point: Hanselmann’s work ethic is almost as impressive as the work itself. That work ethic by itself does not tend to greatness, as many tireless mediocrities will gladly attest, but it does help greatness lean nearer itself.

So what’s it all about, then? Well, it’s about a lot of things, which we’ll get to by and by. But, I mean, you were awake last year, right? You remember it being eventful? That’s what this thing is about. Maybe their precise adventures don’t quite map onto yours or mine but the fictional characters here are responding more or less in real time to the same events as you and I also experienced. Not the daily give-and-take of the political moment, thankfully. There’s no running commentary on whatever manner of rank corruption or abject incompetence the former President was up to on any given day, or even really any reference to the news at all other than a few passing mentions to watching it being a gross and unhealthy habit. Watching the news too much is gross and unhealthy, to be fair, and I’m also a hypocrite whose #1 Fandom by hours consumed these past years is almost certainly Morning Joe. (It’s on when I’m awake. I don’t judge you.) Did you pause a minute and suck your teeth in brutal recognition? I’m sure at least a few of you did. That’s another very 2020 sensation, actually: the harsh realization that our media consumption has to some extent consumed us. And it’s never the good media, just what we like - crucial and damning difference. We give our lives to screens, just like the one you’re staring at right this minute.

Blink. Don’t hold the phone that way. That’s why you’re sore all the time, dingbat.

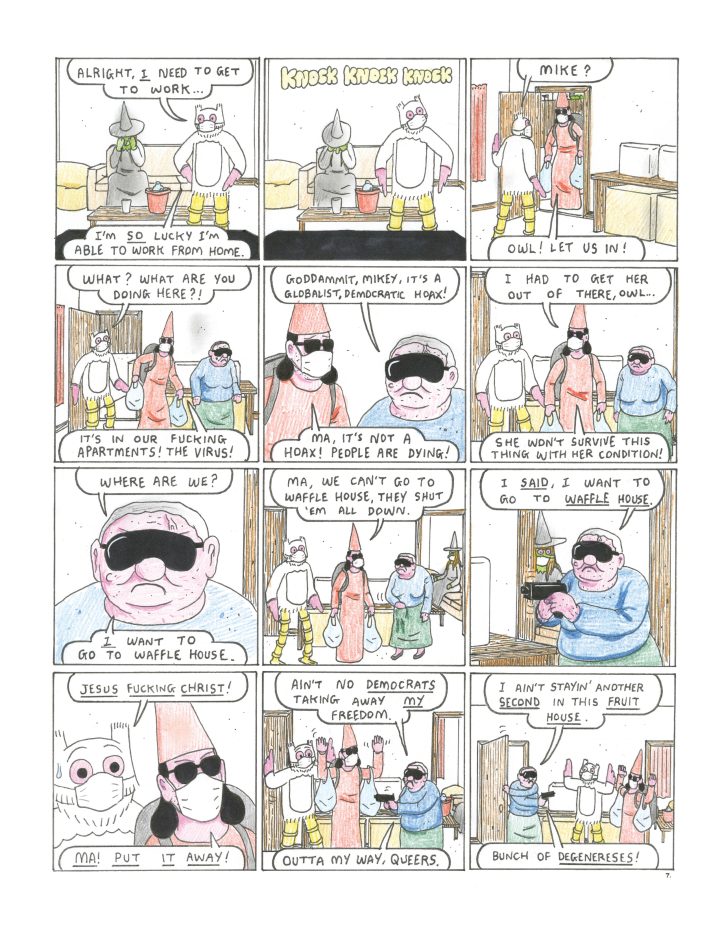

Although the story was developed and created simultaneously, in response to events experience in real time along with the rest of us bums, it reads as a remarkably well-structured narrative. You know how it starts, we all know how it starts: one day people were sitting around at home and heard that Tom Hanks had the plague. That milestone doesn’t come up, but the story does begin at that moment, that initial “What the fuck?! ... this don’t look good” felt simultaneously by most of the country in the middle of March 2020. It was the moment the events of far-off exotic places like China and Italy - perhaps glimpsed on the news, in passing? - became suddenly real for the residents of Poughkeepsie. The theoretical discomforts of a terrible emergency in a distant land had suddenly become the real terror of prolonged crisis.

But then, forgive me, I’m only recapping something you already know, because you lived through it too. Ah, yes, you smile ruefully, there it is indeed. What a thing to find, the great gaping maw of history waiting for us all at long last, mouth full of bloody fangs. And after such a long and cozy interregnum!

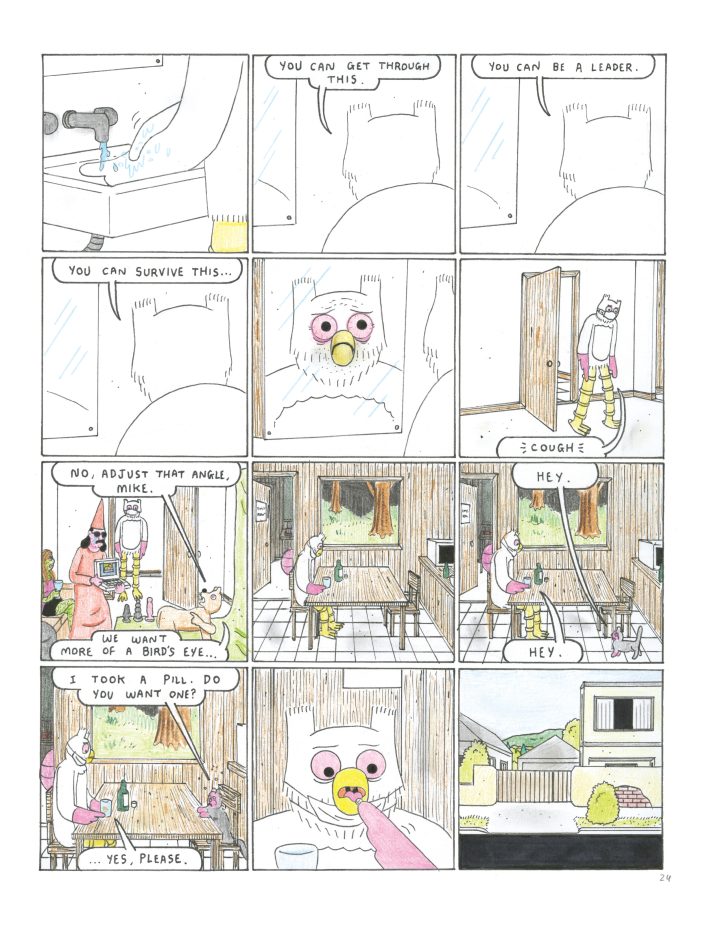

So how did our pals Megg, Mogg, and Owl react to news of the pandemic? About as well as you and I did. Mogg retreats to his room to fixate on watching the news. Megg freaks out about her Animal Crossing preorder. Owl takes a moment to metabolize the certain fact that he is going to be solely responsible for ensuring any of them survive the ordeal. Then he cleans the house, because that’s what we all did back in the early days when we were spraying our mail with bleach. Given the information in the last few sentences, it shouldn’t surprise you in the least to hear Owl is the first person to get the ‘rona, at which point he and his talking knife are locked in the garden shed. Not the last to be so confined.

By that point, of course, the house has gotten fairly crowded. The moment the news hit Werewolf Jones and his boys were already on the way, as were pals Booger and Mike. Of the five people I just mentioned two will come out as trans before the end of the year, because yeah, that’s what happens when you lock everyone up in their apartments and give them nothing to do but stare into their bellybuttons. Things are going to come out, in more ways than one. I mean, speaking from experience, I personally figured out I was trans during a period during which I spent a lot of time alone in my apartment staring at my bellybutton. It’s practically a trope.

Gender bubbles up around the edges through the entire piece, as it seemed for much of 2020. That’s hardly new. I came out in 2016 and I wasn’t anywhere near the beginning of a crest that still hasn’t really abated. There were more of us than people thought, even if still nowhere near as many as our more virulent haters like to imagine. It was in reaction to these facts that those same haters, who do not like the reality of our changing cultural landscape, began the scorched earth crusade of media malpractice and political spinelessness that continues unabated through to this very moment. You can see them in real time following the exact same slanderous playbook they pulled out in the early 80s. Shameless lack of imagination, right down to a handful of beloved Anita Bryant figures immolating their credibility right here in public where everyone can see. Speaking of which, those wizard books pop up early in Crisis Zone - clearly something of an existential matter for the socially conscious magic-using community, represented here by Megg and Mike. RuPaul is mentioned as well. These small but real betrayals compound and complicate, as in life.

The last few years’ developments in moral sentiment, yet fully undigested, have piled in sufficient quantities across every field of human endeavor. This looming bulk reckoning formed a significant part of the sensory overload of 2021. A relentless background static for the marginalized and empathetic in all walks of life. It’s harder to relax when you don’t know which of your favorite artists contribute materially to people trying to hurt you or your loved ones. Certainly no easier when you do. Extraordinarily difficult to fall asleep knowing that the next time the most feckless political party in the world loses a national election to the most ruthless some gormless chud in a Hawaiian shirt is going to throw me and every queer person you know out of a helicopter right before posting the video to 4Chan. Reality of our changing cultural landscape notwithstanding, I’d stock up on Eucerin now in anticipation of the hand-wringing.

Anyway. The multiplicity of trans experience playing at the boundaries of the narrative gives the story a variety that is almost completely absent from any other portrait of trans life you are likely to see. At the risk of provoking startle and dismay in the faint of heart, not only do multiple trans people often cluster for company and protection, but within those clusters exist multiple kinds of trans persons. Although you are more likely to find trans people in the media now, you still aren’t as likely to see a good representation of our community or our actual internecine controversies. Trans people aren’t a monolith, we disagree on many things amongst ourselves, even if most of us agree on general principles of common cause against political enemies. (“Most” and “general” are both doing a lot of work there, I recognize.) There are in fact as many different kinds of trans experiences as there are trans people.

There’s no owner’s manual for this shit. It’s difficult to remake yourself. These characters are familiar to me. In a time of crisis Booger becomes distraught over losing garbage bags full of thong underwear, eventually holding a funeral for the underwear lost to inferno. Mike becomes Jennifer somewhere in the middle there, and initially refuses to change anything at all about her outward presentation for fear of conceding too much autonomy to expectations. Both are ultimately overcorrections, extremes of aggressive frivolity and passive-aggressive stasis in the face of catastrophe without and apocalypse within. Different kinds of armor. I’ve known both people and I’ve been both people.

It’s hard to figure out how to be a person while the world is ending and everyone is looking at you like it’s your fault. As the saying goes, bimbos are carved from cold scars. A quick shot of Booger snatching off her wig to expose a bald pate in a fit of self-lacerating anger seems more brutally naked than anything else we’ve seen in hundreds of pages of Werewolf Jones sticking foreign objects up his ass. Likewise Jennifer unclenches a bit and realizes that not changing to spite others was as much a concession as changing in a certain way to conform. Compulsory gender’s a fuck. Deprograming hurts all around. Transition is ultimately and most importantly an act of healing and healing looks different for everyone.

The third trans person under the flag of New Fucktown is Werewolf Jones’ kid Diesel, who becomes Desi. No one is really certain whether she’s sincere or acting out for attention because she’s an amoral grifter, but they all just shrug and more or less go with it. In all seriousness, if more kids made a habit of pretending to be another gender for a month or two for yuks the world might just be made a better place. The simple truth, however, is more likely that trans people can be amoral grifters, too. Why, one of them just ran for governor of California! The past few years have shown us it's a viable career path across the political spectrum. Check your privilege, flatscan.

But these are ultimately just themes, and heavy themes at that. I’d be remiss if I left you with the impression that the book is anything other than first and foremost fucking hilarious. I haven’t laughed so hard at anything in years. There are many long sequences throughout with a “gut-busting guffaw” on nearly every page, which actually makes for an exhausting read. How about that? I literally had to put the book down, multiple times, because I laughed so much it fucking hurt. When was the last time you did that? Hanselmann can do it on a daily basis and asserts that he could have kept at it indefinitely were he not stopped by contractual obligations.

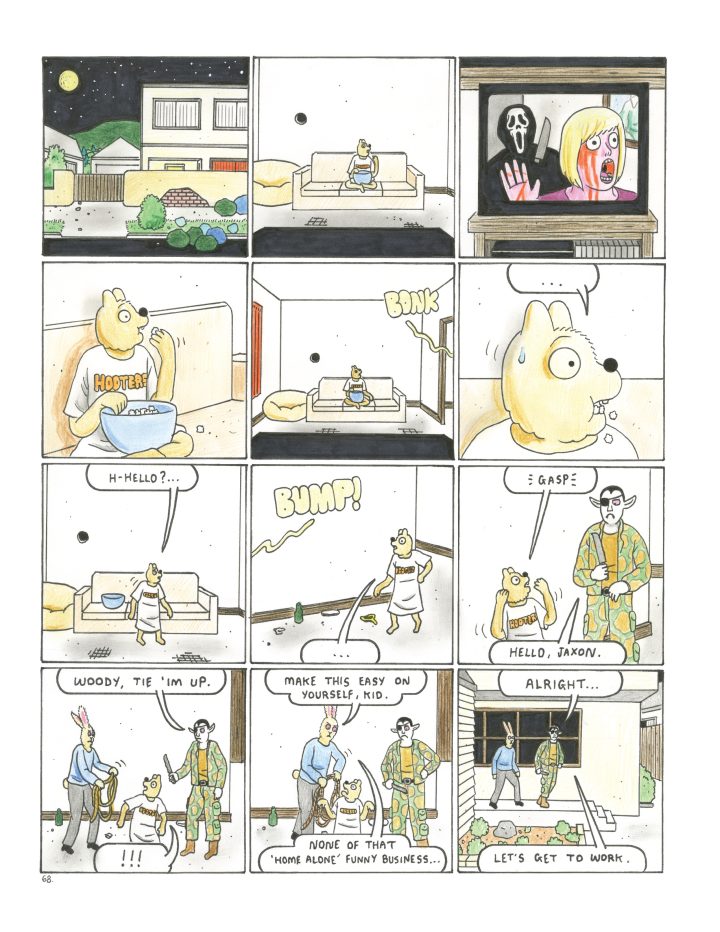

The plot, such as it is, begins with money - or rather, the fact that no one has any. Everything got shut down, remember? All the non-essential employees got fired from everywhere? Even the people who had jobs suddenly also had unexpected expenses. Owl initially looks like he’ll be fine, working from home, but he makes the mistake of leaving his webcam on while Werewolf Jones is around. Owl loses his job and suddenly the only money coming into the house belongs to Werewolf Jones and his webcam. Said webcam becomes so popular (thanks to a blooper reel) it’s picked up by Netflix, which sends a camera crew to the house in order to film the gang as part of a new reality series, Anus King.

Now, wait a minute, hold up, I know what you’re thinking - Tegan, you think, I thought you said this was funny? A Tiger King spoof? Are we still laughing at that? That was admittedly my reaction as well to the title card for Anus King. I didn’t even watch the show and I blame each and every one of you for the fact that I still know what it’s about. (I think I’ve already confessed to far worse just this essay, don’t worry.) Thankfully Hanselmann is too smart to use the premise as anything other than a springboard. But even as the story very quickly veers into multiple strange directions that have absolutely nothing to do with the actual content of Tiger King the framework of the unfolding reality show provides a focus for the escalating absurdity. In this light, given that the reference is really only glancing, it seems as if Tiger King was perhaps a better framing metaphor than I initially gave credit. That show’s brief but intense popularity at the very beginning of the pandemic (in this country, at least) seems in hindsight a flashing red light indicating that we as a culture were entering a dark tunnel and that the only chuckles from that point were going to be increasingly rough. Our collective inability to regulate our behavior in front of a camera was going to form a very large part of that.

So it goes. Werewolf Jones, as it turned out, was extraordinarily good at putting things up his ass. But there’s apparently a difference between putting stuff up your ass for the right reasons and the wrong reasons, and the pressures of fame and stardom - sticking things up your ass for the wrong reasons? - soon lead our pal into trouble. As soon as the cameras and the money become involved the tension ratchets and suddenly people are acting less like themselves and more like caricatures. Jones takes more cocaine even than usual. Everyone else trying hard to live their lives under difficult circumstances has to deal with the magnifying glass being placed on their behavior and the pressure of having to play along with Jones' escalating insanity. Every word, every deed, every past indiscretion gets dredged up and suddenly they’re playing a game of hot potato where the potato in question is cancellation at the hands of a vengeful internet mob.

Why are they vengeful? Well, uh, if I had to hazard a guess, they don’t really have a lot of ways to express anger and frustration in a healthy way - because society is falling apart and almost-not-quite half the country is being fed utter bullshit as to why? It’s easier to go online and get mad at other people for moral lapses, real or imagined, than accept our own powerlessness with grace. It's the illusion of doing something, right? There is no accountability, everyone sees it. Even the most painfully deluded Fox News victim can see the injustice seething at the heart of the beast. As we have learned, it is far easier and more profitable to use lies and manipulation to channel anger and prejudice than systematic critique to focus resolve and solidarity. Personal and cultural grievance make ready bedfellows for political impotence. The moment Anus King is a hit the gang become a pinball in that culture war. Werewolf Jones reacts by chasing the buck as best he can, screaming “get woke go broke!” before rebranding first as an Alex Jones-ish provocateur, then a family-friendly “Blue Lives Matter” activist, and eventually a brusque "apolitical" entertainer. Angry mobs are hiding behind every corner, ready to be weaponized and merchandised by either side, there's really no respite once you enter the Terrordome. And we're all stuck here in the Terrordome.

Is that what life is now? People wield internet mobs like weapons of mass destruction? The problem with Crisis Zone is that it's about as interesting as it is funny, and that’s quite a bit. Just discussing the themes and such makes it seem far more dry than it is. For instance, Hanselmann does a great job of showing the ways in which the “cancel culture” rubric is used as cover for public DARVO maneuvers on the part of public figures who want to deflect criticism, in such a way as is often perfectly calibrated to backfire on the initial accuser, or at least an inconvenient bystander. It becomes a rally point for whomever the new target of the mob is. It’s certainly a much different phenomenon, by order of phylum, than Jennifer’s complicated personal feelings regarding the wizard books. Hanselmann makes this astute point, however, in a scabrous sequence that begins with Werewolf Jones being accused of pedophilia by online “purity teens” and right-wing conspiracy theorists alike, an accusation to which he responds with “None of these pricks deserve my time . . . Suck. My. Fucking. Dick. #PerfectFamily.” He then adds, “apparently cancel culture’s a myth!” A few pages later when the problem fails to disappear he hits upon “We pin it all on Owl! We throw him under the pedo bus! He’s a legit pedo!”

Now, is our pal Owl a pedo? Ehhhhh . . . if the incident reported is as given, Owl once accidentally made out with a thirteen-year-old at a party - oh, wait, sorry, a “mature looking ethnic 13 yr-old,” as Booger helpfully informs us. Does that make him a pedo? Well, he doesn’t particularly seem to be, given as the incident is portrayed as a mortifying mistake he only found out about later, after his friends had been laughing about it for years. He spends a chunk of the book crestfallen at the revelation. Not nothing, but in many neighborhoods the kind of thing that might be settled with an ass whupping, if that. From there the accusations of pedophilia start coming fast and furious, more or less just shit to be flung regardless of veracity. Everyone's dirty laundry is aired in the tabloids. It’s only really harmful if you have a conscience. Turns out Mogg might actually have been the problem all along, having (according to Jones) “‘pretended’ to be a pedophile and broke into a children’s dance recital.” For this sin and so many others he spends much the back half of the book locked in a cat carrier.

Do we even have to say Megg, Mogg & Owl now? Mogg sucks! Used to be Mogg was just a weird little freak who’d do anything for butt stuff - like, OK, we’ve all known that guy, it’s at least a legible phenomenon if not admirable, “there but for the grace of God,” etc. But here with just a little bit of a push he becomes a weird little freak who loves butt stuff so much he burns his life down multiple times and alienates every friend he has. Legible and definitely bogus phenomenon. That he ends up raising a litter of kittens he didn’t want with a woman he doesn’t really like is the most realistic outcome in the book.

Megg isn’t much of a presence throughout the story, plot-wise. The nature of the crisis is such that the primary axis of conflict comes down to Werewolf Jones vs Owl, raging id against long-suffering superego. The problem is that, at first, it really does seem as if Werewolf Jones is set up to thrive better in the carnivalesque atmosphere of the early pandemic. People were scrambling. The precarious nature of our lives in these United States was suddenly laid bare across every strata of society and in that moment of great peril and possibility it looked as if the Werewolf Jones of the world might just prosper. Sure enough, when things get tough he has a plan and manages to keep food on the table and local businesses supported at just the moment when Owl’s stable employment disappears. (Due to Jones’ hijinks, mind you.) But the rest of the book consists of the gang facing the escalating consequences of that moment, as the abrasive media empire built from Jones’ improbable rectal talent comes to dominate and influence every aspect of their lives.

Andy Warhol was dead wrong. 15 minutes was far too kind. The true hell of the future is that we are all stars now, all the time, whether we want it or not. And we’re not just talking about nonconsensual CCTV surveillance, although that specter certainly looms omnipresent with virtual work and education. These necessary lines are blurring, as Owl’s plight illustrates. But we’re also talking about willing surveillance, self-surveillance. The pandemic brought with it a virtualization of so many aspects of social interaction - or, perhaps more precisely, the formalization of already nascent digital trends - producing such a sudden shift in behavior patterns that we have not even begun to understand the implications. We’re all always looking at screens, and now we must also determine how to present ourselves for those screens.

We now reflexively accept an insidious understanding of personality as something expressed in the form of branding. That carries on its wings the unsettling realization that our personality is suddenly being dictated and projected to a distressing degree by the reactions of people we don’t know. This seems like a very basic thing to have to remind us all, but your personality should be informed and shaped by yourself, first and foremost, and then and only then people around you and in your community who you know and love and trust. Not a horde of online strangers demanding you change on a dime to suit their whim. That’s not personality, that’s peer pressure, and god damn it just because it’s true doesn’t mean it still doesn’t sound dorky to say out loud. You are not immune to peer pressure, bucko! Parasocial relationships are a public health menace on par with misinformation. People with a shred of online notoriety can quickly become nothing more than the sum of the schtick and tics they used to keep butts in seats.

Want to see this principle in action, albeit on a microscopic scale? Go back and reread those first few paragraphs of this review - you know, the opening paragraphs containing long run-on parenthetical clauses turning on sudden interjections, unnecessary forced references to Dante, Sophocles, and Marvel Age, as well as an immediate plunge into deep omphaloscopic waters. Think I don’t understand schtick? Think I’m not sitting here ladling it out in careful doses to keep y’all engaged? Think I don’t worry about falling into self-parody, that I don’t even feel a little guilty sometimes for overshadowing the books themselves with my “trademark” “wit”? Yeah, I do. Oliver didn’t let me use the first person pronoun for a good reason. But just the fact that I casually referred to an industry pal by their first name - a figure you may not even know! - well, who does that? It’s annoying, I know it is. Took me decades to figure out how to do that - how to talk to you directly, to know how to talk about inside baseball in away that’s legible and even inviting to the uninitiated, to know where to compromise and where to stand, how much I have to pander to make it up to an editor when a piece is really late. (Stay tuned, kids!) And I write fucking comic book reviews - in the grand scheme of the world you’d be hard pressed to find a less important pastime, we must all acknowledge, even in these august pages. But I do take it seriously, I pay attention, and people seem to appreciate that.

Now, the point here is that it took me literal decades of daily internet usage to figure out how to establish and maintain the boundaries between my personal and professional lives. To figure out how much of my personality I could dole out in the form of caricature before I hurt myself. To minimize harmful online interactions, and figure out what parts of social media had value and which were harmful. Decades of living and working online. Suddenly everyone is drinking from that firehose all at once.

I found Hanselmann’s notes fascinating to a large degree because of his discussion of how the work was influenced by the audience during daily serialization. A lot of the feedback sounds counterproductive or just plain trolling, but something important can be learned even from bad-faith negative criticism. Someone reacting poorly is still reacting. That kind of febrile hypersensitivity, typical of all audiences in the present moment, is usually impossible to please. But the real-time interaction with these ideas that emerge in the strip - sometimes defensively, sometimes facetiously, sometimes even in direct conflict - is nevertheless productive, if perhaps annoying to Hanselmann in the moment. That’s the tone of the book. There’s unhelpful static at every turn because 2020. But the triumph here is that Hanselmann figures out how to play into the static. He takes the criticism seriously, even the bad criticism, and what that means in practice is just learning to focus. To say precisely what you want in just such a way that you absolutely cannot be misconstrued. A voice carries with that kind of focus. The result is that the last quarter of the book hits like a fucking sledgehammer.

Every page is twelve panels, save only, I believe, the first - the dimensions more or less of a Sunday newspaper strip. It’s important to remember that as well as the narrative flows it was also designed to be read piecemeal. The pressure of daily performance gives the strip a nervy energy. Every facet of the world in these comics has to fit through those little squares. Long establishing shots, street brawls, tight closeups - all pushed through the tiny aperture. I respect that. Reminds me of Chester Brown’s Louis Riel, a sprawling national epic told through a series of uniformly tiny panels. The consistency is immersive: if you could step through the panel you’d find a house with a real floor plan and consistent furnishing.

I have no notes for Hanselmann’s storytelling. Within the strictures of his limited panel designs he gives sequential action, psychedelic collage, tense drama. The degree to which the nine-panel grid has become such a lightning rod in recent years since is dismaying - we’ve got twelve panels here, but it’s a similar principle. In my humble opinion fixed panel pages are to cartoonists as learning the scales are for musicians. It all comes from that. It’s a different kind of challenge if you only have one tiny piece of the page for every separate beat.

There are so many ways the artist can pace a page, big panels and no panels and panels of every conceivable shape and dimension, that the decision to submit to the rigidity of a fixed panel structure carries a formalist connotation. It’s more of a challenge, is what it is. You get the same bit of real estate for massive explosions and tense close-ups. The ability to pull the reader’s eye across the page under those circumstances is purely a product of rhythm. The cartoonist under a static panel regime takes the part of a drummer - using the give and take of action and exposition, close-up and establishing, sequential and non-sequential panels to set pace without any recourse to novel page design. Stick to the beat, hard four-on-the-floor, but fill in the blanks however you want. Turns out “however you want” covers an unbelievably vast swath of territory.

The characters themselves begin interacting with their own audience online as Crisis Zone wears on. Eventually they realize, under those circumstances, inviting the world into their lives more or less without caveat, there is no way to win that game. And that leads to the book’s climax. As strange as it may sound considering just how many jokes there are about butts and anuses (and boy howdy, if that’s a problem maybe you should pick up Monsters instead, it’s also very good, costs about the same, another fine Fantagraphics product, sadly lacks even a single analingus-themed running joke) the ending of the book has actually haunted me, unsettled and moved me in equal measure. Led me to reflect upon life.

This reaction can be partially credited to Hanselmann’s mastery of tone and pacing. I’ve mentioned already that the book is unrelentingly funny. Well, look at that word I just used - “unrelenting.” Does that have a completely positive connotation? No. It doesn’t let up. It doesn’t stop. The tone gets shrill as the story wears on the characters really start to hate each other. The drummer won’t quit, double time. The book was never exactly chipper but it gets darker. Eventually Werewolf Jones is naked with a rifle and a baby tied with a rope around his torso, the house is under siege by the police and a vengeful mob (over the small matter of 38 people killed in a hot tub accident that seems to get strangely more confusing every time its recounted) - things are stacking up. Everyone in the house with a uterus suddenly starts menstruating because of the tear gas in the air (which, while exaggerated here for effect, is apparently a real thing that happens according to the ever reliable Dr. Google). The image of Megg pounding her blood-soaked lower abdomen and yelling “stop fucking bleeding!” is indelible. This leads to an unforgettable sequence with the witch, covered in and out for blood, screaming, “This is all Werewolf Jones’ fault! I can’t get weed and now my pussy is suddenly a fucking hemophiliac!” In response to these criticisms, Jones laces a batch of homemade burgers with poison and drugs so they can commit mass suicide at the behest of David Choe’s ghost. Makes sense to me! (I had to look up who David Choe was, tbh still not sure.)

Not even this works, however, because the gang just wakes up later feeling more like shit than usual and pissed off at the man who tried to kill them because people were after him. Jones had been taking orders from Choe’s ghost for a while, you see, who also supposedly promised Jones not just a place in Heaven but a spot on Joe Rogan - “I’ve got DMT anecdotes!” To which Owl responds, just as would you or I, “Dude . . . Rogan’s embarrassing. And how the fuck is a ghost booking another ghost on a podcast? It’s all the coke and the tear gas.” Everyone is getting constant death threats, too - “I mean, look, realistically it’s just reckless kids, but it’s still not pleasant.”

And this is how it ends, at least the main plot - a man-sized owl brandishing a kitchen knife talks a tiny bit of sense into a naked and weeping werewolf in a Burger King crown. Ultimately, as weird as it seems, Jones has actually meant well for much of the narrative. He was trying to support his family and the house. He is however a wrecking ball in semi-human form, as well as fundamentally insensible to suffering, often up to and including his own. It is impossible for him not to incur collateral damage. Even his hot tub parties end with a body count. The onset of the pandemic brought with it that brief window when, in the absence of any other order, the Werewolf Jones of the world seemed better equipped to take on the upside-down paradigm. That didn’t last long, however, because his solution to being broke - starting a webcam that snowballed into a reality show - created a feedback loop of escalating fame that turned Jones’ brain into a quivering mass of pudding.

Again, Hanselmann’s pacing is uncanny. It’s very rare to find a story, any kind of story, where things always happen at the same clip. Stories speed up and slow down, sometimes people have a conversation for a few pages in between people blowing something up, then you maybe have a different kind of interlude so it doesn’t get repetitive, etc. You keep the reader interested with periodic serotonin dumps - peaks and valley - because keeping up a relentless pace can actually be grating. Accordingly, there are a couple fight scenes throughout that actually work as fight scenes - Hanselmann mentions in the notes readers were restless during serialization as the chapters trickled out, but in the context of the full book the fights are perfectly situated, stretches of grisly physical comedy between people screaming at each other or projectile shitting.

However as the book progresses the rate of events ratchets, until we’re in the last stretch of Goodfellas and suddenly things are going really fast and you just hear helicopters all the time. That’s where we are when the gang wake up from their brief burger comas and confront Jones. Not even death stopped the carnival. This can’t go on. It’s exhausting for everyone, and by that point in the book you, the reader, are exhausted too. As Megg opines, “when I’m not high, this shit isn’t very funny.”

And so the bubble has to be popped. Jones recognizes he’s fucked everything up for everyone and sees in that moment but one path to freedom for his family. He finds a canister of shoe polish and begins to apply blackface in front of a camera (only implied on panel), at which point the cameras are turned off and the show is over. Werewolf Jones is canceled for good.

It’s not funny, but it’s not supposed to be. In the story and for the reader a balloon has been popped. The pressure has been lifted, it’s all downhill now - or rather, denouement, if you’re nasty. But it does the trick. Much of the story up until that point has been concerned with the line - as in, where is the line? How far are we supposed to go? How far will Hanselmann take us? We’re supposed to push as close to the line as we can, or we don’t get engagement. Sometimes the only way to get the needed engagement is to go for the cheapest laugh, and the price of laughs is sharply prorated based on talent. But here, finally, in one gesture, we reach the line. We flinch, as readers, because we know it’s not funny. Maybe you, the reader, are even groaning yourself. All the air goes out of the room. Good and evil do still exist in this world after all. Actions have consequences.

That we still agree on there being a line is important. And so the reader is left with the crucial question - did the book cross the line? Did it go too far? And I don’t think that’s a bad faith question in the least, I think that’s the crux of the matter and a question the book itself poses: why did it have to go this far for people to see how bad things were? If there’s a point beyond which reasonable people can agree there is no reasonable good-faith misconstrual or satire - the book posits that it is there. And of course it’s not like the act kills Jones’ fanbase completely, it just narrows it significantly, albeit to one even he rejects out of hand. Hopefully no one you have to see this Thanksgiving.

If we agree that there is a line, what does that mean? Does the way the point is made undercut the message? Why in the holy fuck did we need such a terrible reminder of cruelty and hatefulness to see that maybe we should treat each other better? Maybe treat ourselves better? It’s clearly not a lesson that travels far beyond the immediate confines of their household. The circus maybe paused a few seconds to clear its throat, but it never stopped. Just moved on down the line.

The final passages of the book occur in something resembling an irony-free atmosphere. Things shake out, ultimately, just as they are. The crisis is the new reality. The sound of the fury of the previous year has resolved, at least within the new family unit kluged together in the wake of Werewolf Jones being sent to prison. It’s not as if that much has changed, in some respects. But a great deal has been clarified. Those things which were not necessary were revealed as such, those things which were vestigial but kept in place through the threat of violence were similarly laid bare. On scales both domestic and national.

Although the book reflects just about every significant event of the previous year, it doesn’t devote any time to recounting the news itself. There are no dates or news updates. No reference to the ongoing pandemic for long stretches, other than that sometimes everyone has a mask on and sometimes only a few people do, and you definitely always notice, just like here on Earth-Prime. There’s no cartoon depiction of the final moments of George Floyd, thank God. But these events still happen in their world, and our gang stumbles through that aftermath just like the rest of us. Except, not really, because they’re in Seattle. So they see a good deal more of it than did most of us country mice!

Hanselmann’s decision to avoid any kind of contextualization other than that offered by the characters themselves gives the story an unmoored quality. Similar to how time itself worked last year! So many familiar landmarks were removed. Hanselmann’s refusal of any grounding context also limits the action to a rigorously local perspective. With this in mind, Hanselmann through his characters makes two basic observations regarding the police riots and protests that raged across most of 2020: one, it really was the police versus (almost) everyone else, and two, there sure were a lot of people out on the streets for reasons that didn’t have a lot to do with Floyd (or Breonna Taylor, or Philando Castile, or Tamir Rice, to mention but a few). I would assert with a years’ hindsight those observations hold up remarkably well, at least compared to much else asserted at the time.

Again, we are confronted at every turn by the incredulous mantra of 2020: why did it have to go this far for people to see how bad things were? Across the year that sentiment was felt across every context as the stress of a sudden crisis revealed very deep cracks in the foundation of our collective. From law enforcement to national politics we have learned in real time the consequences of the worst people in the world thinking everything is a reality TV show. Will nothing else cut through the savage din but sheer shock? A postscript from 2021 indicates that the characters know full well, as do we, that the cyclone hasn’t stopped spinning. Are you worried about the ongoing coup and federal prosecutors’ feigned indifference in the face of same? Government inaction on climate change? Well, don’t forget hundreds of people are still dying every day in this country from a disease for which we have an excellent vaccine! Ob la di, ob la da.

Does all that sound heavy? There is nevertheless a sense of hope permeating these final passages, palpable and real despite the onrush of tragedy. As improbable as it seems, the family unit formed in the household in the wake of Werewolf Jones’ imprisonment and passing comes together. They have the hard conversations they’ve been postponing for hundreds of pages. They sit down and they play Lego with the kid. How important is that? Nothing more important. In the postscript it’s revealed that Owl gets a job working construction, which he probably saw as a step down at the time but which also seems to be good for him. Megg gets bored with farming simulators and plants a garden in the backyard. It’s not particularly subtle, but it’s not really meant to be. It’s even a little didactic, when you lay it out end to end: put your phone down and go build things. Grow things. Maintain what we have. Prepare for whatever’s next.

So we end in a place that has become very familiar, more or less the present. We are being driven insane - not figuratively, not pejoratively, but actually clinically unwell - by the constant bombardment of social media and the gamification of reality. The zero-sum logic of influencers has crept into every facet of our lives. If anything 2020 revealed the degree to which it had already been pressing on our thoughts and feelings, for years. I personally stepped back from a lot of social media in 2019, partly because my editor mentioned doing something similar at the time (I mention by way of pandering, because this shit is late). I talk about my life and politics a lot less and old comics a lot more and my life is so much better for maintaining that barrier. Far healthier if I feel the need to pop off about something, and more productive, to write a real essay to send to my real editor for my real readers. Certainly healthier than getting in an argument with a virtual stranger. Haven’t had an argument online in well over a decade! I can write anything I want in an essay because people who disagree with my politics or personal life do not have the patience to read this.

Now, the revelation that social media is driving us mad really isn’t novel, and to that point its worth observing for posterity that the arrival of Crisis Zone coincides with both a string of whistleblower exposes about the tech industry in the pages of the Wall Street Journal and Congressional hearings to that effect immediately thereafter. Three different signposts, albeit of varying degrees of gravity, but all pointing towards the same nauseating conclusion. We as a society are at least becoming aware of the problem. Does the information arrive too late to do any good?

Was 2020 our rock bottom as a people? If we know what’s good for us! It certainly was for the gang in Crisis Zone. It doesn’t mean that the bad things in the great wild world aren’t there. Rock bottom doesn’t mean the problems are fixed, it just means you see the problems. The white nationalist militia members who shop at the same supermarket I do haven’t gone anywhere but neither have we. Do we drive ourselves mad with fear or do we live our fucking lives? We live our fucking lives. We heal, we grow. We touch the damn grass, touch it real good. That’s our win condition. We need to shepherd our strength to protect what we have. Victory is another day.

Except . . . the hope that emerges is a fragile thing. Werewolf Jones’ passing still leaves a hole that will only be healed with time. Megg’s garden dies because she can’t remember to keep it up. According to my vulgar Freudian schema, Megg has been the ego trapped between oscillating ids and a harried superego. Accordingly she spends most of the pandemic stoned off her gourd, because there sure weren’t a lot of reasons not to be. She can’t function. When she briefly runs out of weed late in the book she turns semi-feral. Her usually high tolerance is reset by the dry spell, so next time she’s high she pisses herself at How I Met Your Mother. Only the truly gone know why “Swarley” is the worst possible reason to piss yourself. Shout out to clinical depression!

She gets the best action beat in the book, during the final fight, after Jones’ ex Susan breaks into the house to steal her kids back. After getting her ass kicked Megg does a bong rip that functions similarly to a can of spinach and pops up ready for round two, roaring, “Come at me like a double-decker bus, cunt!” All this while naked, except for a thong, while listening to the Smiths on her headphones (hence the “double-decker bus”). Not quite the last panel of Uncanny X-Men #132 but you at least see the familial resemblance.

Throughout the book Megg avoids calling her mother. For much of the length of the pandemic. Finally she does, and longtime Hanselmann readers can probably imagine how it goes. Megg’s mom is a self-destructive addict, exhausting, emotionally immature, and in every way completely unsuited to be a parent. Completely unable to take care of herself. She exists as a specter of guilt on the edge of Megg’s memory, never leaving her thoughts, never resolving. Growing up with a child for a parent leaves a hole that never quite heals. The experience instills a profound inability to deal with the grown-up world, predicated on having survived an erratic childhood defined primarily by the personal insecurities and eccentricities of the parent. She knows how to live for and around other people but never learned how to live with herself.

2020 was all about fight or flight. With threats from every direction Megg shut down. She wants to break out of the funk of 2020 along with Owl and Jennifer and the kids, but she wasn’t really down about the pandemic in the first place. She was down before the pandemic even got there. And sure enough, like clockwork, the final pages of the book bring with them bad news for Megg, carrying the threat of possibly being sucked back into the miasma of family by way of an emergency. Sometimes there’s no way to extricate yourself, and you know it, and you live with a trapdoor under your feet because there’s just no one else around to cover the shift. I hadn’t really seen that aspect of my 2020 reflected anywhere, but I found it here, and I wept to see myself.

So the part that killed me? The part that really killed me? Before that, during the follow-up special - featuring cameo from an appropriately nihilistic Joel McHale - a passing comment by Owl on Megg, about her personal growth since the end of the show: “I’m essentially just treating her as one of the kids.” Megg doesn’t have any mental reserves left. There’s no sarcasm, just sincere guileless exhaustion. To which she responds, “I’m trying to do better by the people around me . . . and myself.” Dear reader, have you ever wished a man-sized owl would come to your door and offer to take you away to his Seattle tract home, where you could play Lego anytime you wanted and gather around for family dinner every night? Because in that moment I realized I wanted nothing else more, had never wanted anything more than my very own Owl.

And as much as I felt for Megg, in that moment, I also felt for Owl, and wondered if Owl also hated himself for being stuck being Owl. He’d probably much rather not, but because there’s no one else he is. And I can relate to that. Personally, my pandemic sucked for a lot of reasons that had nothing to do with the pandemic and owed more to the years of being stuck on a farmhouse taking care of my dad during a long illness - late stage Parkinson’s, if you’re curious. All that’s left now is the worst of him. I was in this place before Covid and I’m still here now. I was feeling isolated and paranoid before, then I got to see everyone else turn isolated and paranoid, too. Only you folks probably at least got to pick what you watched on TV. News is about the only thing the three of us can all settle on, most of the time. I haven’t had the time or cognitive function to read anything but comic books for years and every spare moments or most of 2021 has been devoted to writing. This essay took almost a month to write, and that’s a month of me writing more or less every spare moment. In a vacuum, for me, this is two days’ work! Can you imagine the sheer mental constipation? Under present circumstances writing has become the most excruciating and drawn-out torture. I don’t get to shower as often as I’d like. Plus I got a concussion last week - yeah, knocked into a tree branch walking the dog, because she likes to make sudden turns in the orchard. That certainly didn’t help this essay get written any faster.

I know I’m not the only person living that reality. I’m one of millions of people who are actively being kept from participating in the public sphere in any capacity because the complete collapse of the social safety net has opened a chasm under most families. There is no sufficient elder care, no sufficient health care, no sufficient mental health care, no sufficient public welfare program of any shape. There are however lots and lot of people, like myself and Megg, who can just afford to

. . . aaaand that’s where I left off the other night, before I went to the hospital. Worst pain I’ve ever felt! Thematically resonant to this review! The ultimate (non-dairy) culprit, if you’ll pardon my discretion, was stress. Stress and exhaustion. They gave me a morphine shot and I barely felt it. Because I am nothing if not committed, I couldn’t help but reflect in my extremis - shivering and soaked with sweat, freezing on a hospital gurney - on this still unfinished review, and the degree to which my professional frustrations of the last years were contributing to my stress, and how glad I was to have Obamacare. I got to take a ride in an ambulance, more or less free from worry, just because I happen to live in a state that makes it (relatively) easy to sign up for a federal program that should be universally available. Doctors and medicine are present in the Crisis Zone only to the degree that they are ruinous traps to be navigated around like so many Scylla and Charybdi. A gruesome running joke features tertiary hanger-on and shameful trustafarian Ian refusing to go to the hospital when grievously injured, despite having health insurance, out of solidarity.

The lack of basic social services and subsequent precarity, in both our real world and theirs, makes it extraordinarily difficult to build and maintain anything beyond the exigence of immediate survival. Every moment of resolve and growth is met by an equal and opposite moment of institutional decay. In our real world we spent the better part of the year staring in disbelief at the government’s lack of response - absolutely, criminally negligent, across every level of the disaster. There isn’t even the pantomime of that disbelief in the Crisis Zone. People know they’re on their own. Access to medicine is a fragile perquisite, law enforcement purely an expression of institutional dominance. If they’re coming, they’re not coming to help.

It’s hard to pull yourself up from the gutter when there are no handholds and everyone around you is a similarly flailing. Even maintaining the simple cohesion of a family unit can seem an impossible luxury in a world where every incentive exists for families to splinter. People are ground up like hamburger improvising individual solutions to problems that can only be effectively solved through collective action. Must be nice to have enough money you don’t have to burn every other resource in your life like kindling to survive inevitable problems. The final passages of Crisis Zone left me both inspired and enraged, by the basic stubborn endurance of the people left to survive in the wake of disaster as well as the intentional and malign institutional neglect that forces them to live hand-to-mouth, constantly waiting for the other shoe to drop. Through the lens of 2020 its difficult to see the wreckage of our public sphere, every layer of it, as anything other than a ruinous rearguard action on the part of robber barons, solely designed to stymy the awakening of class consciousness among people too bruised and divided and narcotized to think.

But that’s perhaps a step too far for you, and certainly for Hanselmann, or my editor, and probably for this magazine as an institution. Ah, well. It’s that faith in the future that keeps me going. Old fashioned, I know. Practically Hegelian in its fustiness. But everything I have written this year has been produced with that spirit, and against these headwinds. I believe in the future. I’m still trying to build for the future. Last I checked its the only game in town.

So do we end with that note of real and palpable hope? Or do we keep the camera going and wait a few minutes until everything once again falls apart? All a matter of perspective! One step forward, one step back. Doesn’t make the good less real or the bad more. When do we get to leave 2020 behind? Where do we find the strength? The world leveled up and we need to rise to the occasion. I resolve to watch less Morning Joe - surely I can find another, cleaner trough for rooting around in liberal ideology? Surely the world’s worst key party can keep it up without me? Maybe I’ll tune back for special occasions. Check in on the gang. Furthermore maybe I’ll even learn to not drink the egg nog when it doesn’t taste right. We shall see. But we have to leave the crisis behind.

It sometimes seems like 2020 is never going to end, I know. Believe me, I know. The problems haven’t gone anywhere. You want to sit and worry it some more. But at some point, just as with this essay, whether or not we feel we have reached a satisfactory conclusion, we must simply stop and move on with our lives.