If I had to choose a single panel from Peter Bagge’s Credo to represent the particular nature of his style of biography, it would be the third panel on page 42. Rose Wilder Lane, the prolific American writer, world traveler and political theorist who collaborated with her mother Laura Ingalls Wildler of the beloved Little House books, has just had a falling out with “Troub,” her constant companion for the past decade. An angry Troub has put on her hat, grabbed her suitcase and is in the process of storming away from the Mansfield, Missouri home they shared with Lane’s parents and what her mother Laura characterized as “a bunch of strange, unattached women,” a circle of subversive creatives that Lane formed and supported.

Lane has fallen to her hands and knees in the middle of the road, all but begging Troub to stay, as without her she’ll be all alone. Bagge has drawn her head bigger than usual, as if it has swollen with emotion, and a halo of sweat drops appears around it.

Troub shouts over her shoulder that another of their friends will be there soon, “And there’s always your mother…”

“No! >Sob<” Lane replies. As if to justify the sob, her mother appears in the background, near the horizon. Oblivious or indifferent to her daughter’s emotional state, she cups her hands to her mouth to shout, “Rose! Get up! You’ll ruin your dress!”

I’m not sure if that is precisely how the scene played out in real life, but I’m certain it is emblematic of how Bagge’s pure cartoonist aesthetic can transform episodes from the lives of his subjects (Prior to Wilder Lane, he produced books on Zora Neale Hurston and Margaret Sanger). His artwork simultaneously heightens the emotion and softens the abrasive nature of heart-breaking episodes, while defining the characters’ relationships more directly than paragraphs worth of words ever could and, incidentally, presenting a well-constructed comics gag.

That panel is something of a punchline to the two that precede it, in which Lane tries to talk Troub out of leaving, and Troub points out that Lane has all but pushed her away. These are the top tier of panels on the page, and one could take scissors to the book, cut them out and paste them into the comics section of most newspapers and they wouldn’t be too out of place; it reads with the same familiar, comfortable cadence of a popular newspaper gag strip. In fact, much of the book is composed of similar scenes.

That panel is something of a punchline to the two that precede it, in which Lane tries to talk Troub out of leaving, and Troub points out that Lane has all but pushed her away. These are the top tier of panels on the page, and one could take scissors to the book, cut them out and paste them into the comics section of most newspapers and they wouldn’t be too out of place; it reads with the same familiar, comfortable cadence of a popular newspaper gag strip. In fact, much of the book is composed of similar scenes.

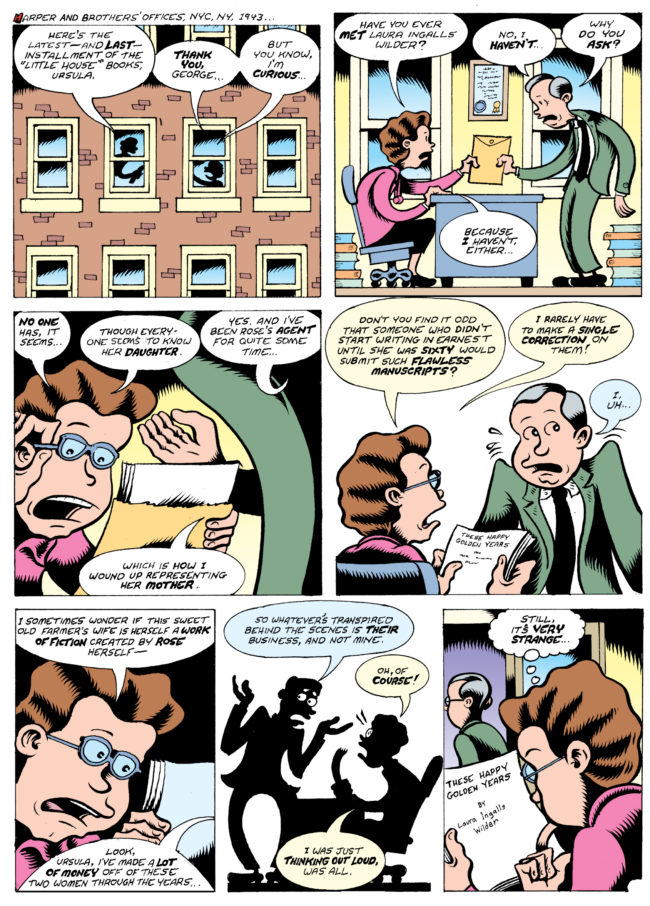

Lane’s complicated relationship with her mother is at the heart of Credo, which takes its title from a political treatise she wrote at the encouragement of Saturday Evening Post editor Garet Garrett. While which woman did what (and how much of it) is an ongoing, and probably now unsolvable mystery regarding Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books, it’s true that Lane loved to edit and ghost-write, and helped her mother ready, sell and promote her manuscripts. Which of the two was the “bad guy” in their relationship is also something some continue to argue over. In both cases, though, Bagge is pretty agnostic, depicting arguments between the pair over certain elements of the books, and dramatizing publishers wondering aloud about how much of the writing Lane did, but deciding to stay out of it for their own good (“Look,” Bagge has Lane’s agent George Bye tell Little House editor Ursula Nordstrom in one scene, “I’ve made a lot of money off of these two women through the years… so whatever’s transpired behind the scenes is their business, not mine.”)

The pair often seemed to hate one another, but they were also utterly devoted to one another, and Lane spent an enormous amount of money and time on her parents, ultimately changing the course of her life to be near them and take care of them both until their deaths.

The pair often seemed to hate one another, but they were also utterly devoted to one another, and Lane spent an enormous amount of money and time on her parents, ultimately changing the course of her life to be near them and take care of them both until their deaths.

Bagge’s diagnosis of their relationship--which he convincingly argues in his typically minimal way, with a few lines of funny dialogue and funny drawings--is that not only were they both extremely stubborn women, they were so much alike that they naturally drove each other crazy. In one 1949 scene, when they are both old ladies, they visit a cafe together, and both insist on sitting in the back, facing their door. When the waitress questions if they’re looking out for something, they both have different answers--For Lane, it’s communists, for Wilder, it’s locusts--but they adopt the exact same poses and expressions, appearing to be the same woman, only at different ages, and born in different ages.

Bagge covers Lane’s life from 1889 to 1968, the year of her death, with a one-page epilogue set in 1972. And for Lane, that is a lot of life. As a child, she moves with her family from the Dakota prairie to Minnesota to Florida to Missouri. As an adult, she moves to Kansas City, where she meets a traveling salesman with a devotion to get-rich schemes. She marries him, which is where she gets the surname “Lane”, and moves to San Francisco. After losing a son in premature childbirth, divorcing her husband and attempting suicide, her life gets even more action-packed. She writes for a newspaper, gets a gig ghost-writing autobiographies for famous men in Hollywood (which Bagge dramatizes in a scene of Charlie Chaplin telling her off for taking too much dramatic license), writes for women’s magazines and takes a job reporting for the Red Cross which sends her all over 1920s Europe. She ultimately returns to Missouri, where she constructs a new home for her parents on their land, and moves into their old home with Troub and the rest of their women’s commune (presented by Bagge in typical cartoon shorthand, holding hands and dancing barefoot in a circle, while Laura looks on, trash-talking them one-by-one to her husband).

Back in the states, her political activities come to the forefront of the story. During World War II, at age 55, she takes a “principled stand” and grows all of her own food, while refusing to consume any rationed item. She takes a job writing for “black” newspaper The Pittsburgh Courier, negotiating her fee down so that she won’t have to pay income taxes. Lane is, to the confusion of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover in a funny cameo, being “poor on purpose.”

Back in the states, her political activities come to the forefront of the story. During World War II, at age 55, she takes a “principled stand” and grows all of her own food, while refusing to consume any rationed item. She takes a job writing for “black” newspaper The Pittsburgh Courier, negotiating her fee down so that she won’t have to pay income taxes. Lane is, to the confusion of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover in a funny cameo, being “poor on purpose.”

With so much to cover, Bagge plucks anecdotes from Lane’s life, rendering them in his signature rubber-limbed, funny-faced style, replete with the full complement of cartoon shorthand. A lot of it is funny, made funnier still by Bagge’s presentation, and it gets funnier still as Rose ages, gradually turning into her mother visually and in personality, although while Wilder seemed to focus her ire mostly on her husband and daughter, Rose focuses hers on the whole world and the many injustices she sees within it, see-sawing between being completely irate and comically motherly, as when a state trooper visits her in 1943 to ask her about a subversive postcard she sent.

In one panel, she literally jumps up and down, shaking her fists and screaming, “Then arrest me now, because I’m as subversive as all hell!!!”, while the trooper’s hat falls off the back of his head and, in Bagge’s telling, thinks, “Yikes! This lady is bonkers!” In the next panel, a plate of cookies appears in her hand, and she sweetly asks, “By the way, officer, would you like some cookies? I just made a fresh batch.”

In one panel, she literally jumps up and down, shaking her fists and screaming, “Then arrest me now, because I’m as subversive as all hell!!!”, while the trooper’s hat falls off the back of his head and, in Bagge’s telling, thinks, “Yikes! This lady is bonkers!” In the next panel, a plate of cookies appears in her hand, and she sweetly asks, “By the way, officer, would you like some cookies? I just made a fresh batch.”

Of the three women Bagge has so far devoted a cartoon biography to, Lane may just be his best subject. Not necessarily because her life was more important or interesting, more colorful or varied than Hurston’s or Sanger’s, but because Lane’s whiplash mood swings--Bagge writes in his prose introduction that she suffered from “a clear case of what is now labeled bipolar disorder”--and her lifelong battle of wills with her mother make her an ideal comedic subject. Credo is not a comedy, of course, it’s a biography. But it is funny.

Characters as big, as fantastic, as fascinating and as full of contradictions as Rose Wilder Lane really can’t be invented, even by the most imaginative cartoonists. They can only be found, and their stories re-shaped and retold. In Lane, Bagge has found a real doozy, and the result is a doozy of a comic.