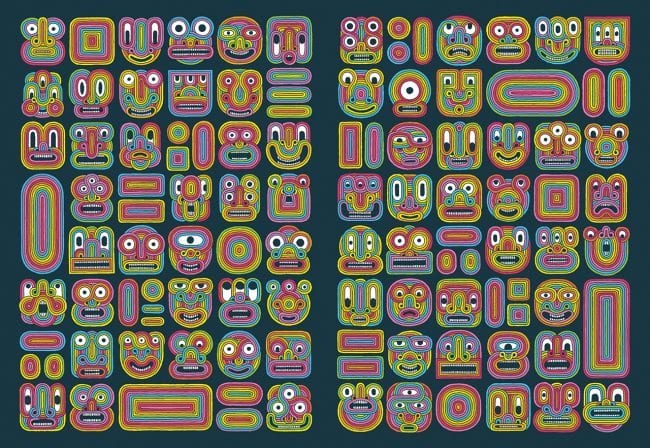

Crawl Space’s cover is a rainbow-color explosion—a geometric face on the cover with a screaming mouth and an eye in its forehead. Filled with colorful detail, it looks like the cover of some forgotten psychedelic record album.

It doesn’t let up inside. The inside cover pages feature grids of 71 grinning, wide-eyed faces, all drawing with multicolor lines. They appear manic and alarmed. The title page is basically similar—a single somewhat sinister grinning creature staring at the reader, portrayed in intense rainbow colors. Then the first page brings it down to earth—a washer and dryer portrayed in stark black and white, floating in a page of full-bleed black. Then there are several more pages of psychedelic color as two characters start interacting in a densely-drawn environment of pure color. One of the characters, Daisy, seems to be guiding the other, Jeanne-Claude, who is experiencing anxiety. Daisy is guiding Jeanne-Claude on her first trip down the rabbit hole. They drink tea from a little tea-pot-shaped creature (that changes color in each subsequent panel), which causes the hallucinations to intensify.

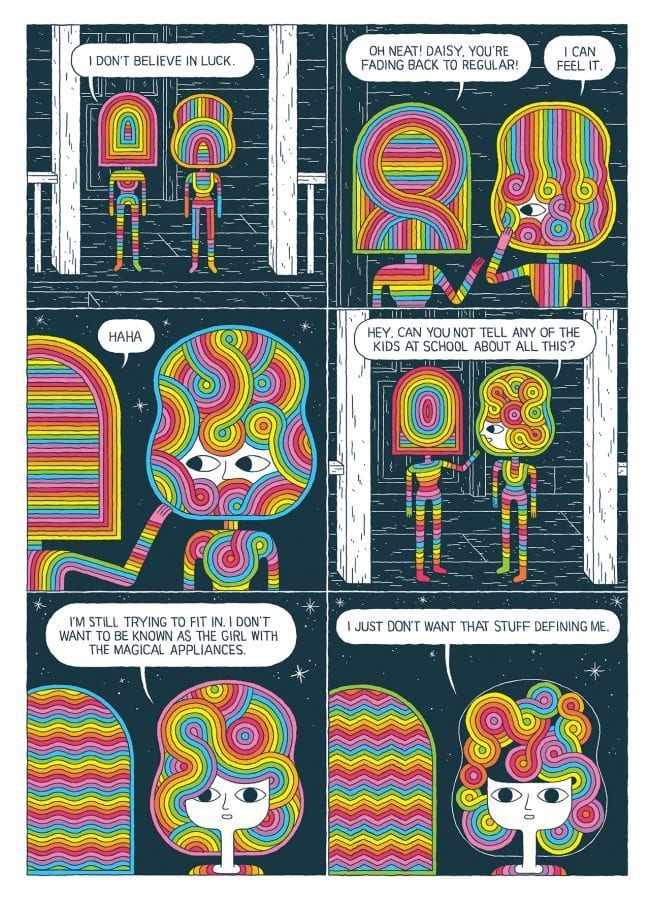

Then the two rainbow colored people climb out of the washer and dryer back into the ordinary world. Daisy quickly reverts to a black and white being while Jeanne-Claude takes longer. Black and white in Crawl Space symbolizes ordinary reality. Daisy asks Jeanne-Claude not to tell other people about the washer and dryer experience. She is “still trying to fit in. I don’t want to be known as the girl with the magical appliances. I just don’t want that stuff defining me.”

This defines the drama. It has all the earmarks of a cautionary drug story—one teen gets into some heavy duty psychedelic drug, tells a friend about it, and it snowballs from there. It is also like a horror story—teenagers discover something that they shouldn’t. The genre of something strange inside the house is a venerable one: The Haunting of Hill House, The Shining, House of Leaves, The Amityville Horror, etc. But the difference between Crawl Space and these stories is that as disturbing as the experience of going into the washer and dryer, it’s ultimately pleasurable. Indeed, the problem seems to be that it is addictive.

This defines the drama. It has all the earmarks of a cautionary drug story—one teen gets into some heavy duty psychedelic drug, tells a friend about it, and it snowballs from there. It is also like a horror story—teenagers discover something that they shouldn’t. The genre of something strange inside the house is a venerable one: The Haunting of Hill House, The Shining, House of Leaves, The Amityville Horror, etc. But the difference between Crawl Space and these stories is that as disturbing as the experience of going into the washer and dryer, it’s ultimately pleasurable. Indeed, the problem seems to be that it is addictive.

Needless to say, Jeanne-Claude is unable to keep it secret. Soon Daisy is taking other friends into the washer and dryer. Daisy takes one of the little critters from the washer-dryer world to school. Lots of kids end up going to the washer-dryer world and start vandalizing the environment. Daisy tries to remind visitors to “remain calm and focused” and “behave with positive intentions.” But these are teenagers. Eventually there is a big party at Daisy’s house when her parents are out of town. The house is trashed as is the washer-dryer environment. One kid remarks to Jeanne-Claude, “I wouldn’t go inside if I were you. Some of the older kids had sex in there!” The dryer is laying on its side and Jeanne-Claude observes, “Sick! Somebody threw up in here!” The creatures there have been abused—a gremlin has his neck caught in plastic six pack rings and one of the teapot creatures has been shattered. Many of the creatures become hostile and defensive. Jeanne-Claude finds Daisy, whose identity has almost completely melded with the environment. (I’m writing out something that is portrayed visually in the book.)

The party is busted by the cops. The house has to be cleared by a pest-control firm (which captures all the psychedelic critters) and Daisy is to be sent off to boarding school. But just before the end, Daisy wanders into a culvert and seemingly discovers a new weak spot between planes of existence.

There are interstitial chapters that discuss how these psychedelic planes of existence are normally reserved “highly enlightened beings” but that some of planes are accessible through “weak areas of the was the cosmic fabric was slightly torn.” The washer-dryer world appears to be one of these places.

Crawl Space ends up being a bizarre combination of genres. It has the elements of a teen comedy movie (complete with the party that gets out of hand), but also a teen cautionary tale (the kind that used to be the popular YA books before post-apocalyptic adventures became the default YA genre). It has elements of drug narratives like The Doors of Perception and Confessions of an English Opium Eater, and the failed enlightenment story (think Weathercraft by Jim Woodring). And let’s not forget the narratives of houses as portals to strange worlds mentioned above. The washer and dryer are analogous to the wardrobe in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. This bizarre mash-up of genres is enough to mark Crawl Space as unique, but I think what readers will remember most about it are the unrelentingly psychedelic graphics. Jacobs’ visual imagination has been the cornerstone of all his books, By This You Shall Know Him and Safari Honeymoon, but it really takes over Crawl Space. It is a metaphor for a kind of heightened consciousness. For an art lover like myself, it is a metaphor that rings very true. Visual pleasure from viewing art is both satisfying and dangerous. Dangerous in the sense that it appeals solely to the eye—it is what Marcel Duchamp called “retinal art” when he rejected in favor of art that is philosophical, religious, moral. Jesse Jacobs wants his readers to have it both ways—he supplies the reader with eyeball kicks while warning against their easy pleasures.