So. Manuele Fior had a couple of excellent and quite different books, 5000 km Per Second and The Interview, both exploring the misalignment of time and progress as a backdrop to very believable, earthy love affairs. Decades and generations jumped back and forth—the style along with them—creating light, dreamlike stories that managed to be accessible and complex at the same time. Then followed a collection of b-sides, and an early book (here I'm following the timeline of English translations only), and now, Celestia—a fully-painted graphic novel that for the first time feels more like an iteration, rather than a new development. It's long and beautiful, and its very existence is a huge accomplishment, though reading the thing left me mostly unimpressed.

Painted comics work best when great restraint is shown, and even then, it is a far greater challenge than limiting yourself to lines and flat fills, which makes the beginning of Celestia all the more remarkable—it's breezy and effortless in its flow, while every panel can be taken out and studied as an illustration. At first, there seems to be no sacrifice in the process—the book works as a book, and as a collection of sometimes unbearably beautiful images, some of them displaying great skill, others not afraid to show naivety. That latter quality is what makes Fior stand out among so many skilled and often samey BD/fumetti artists—he knows when to stop and let the reader see his brush in action, instead of wrapping up each line and polishing each corner. Blutch is like that, too, as well as Catherine Meurisse (still inexplicably absent in English apart from digital editions from Europe Comics).

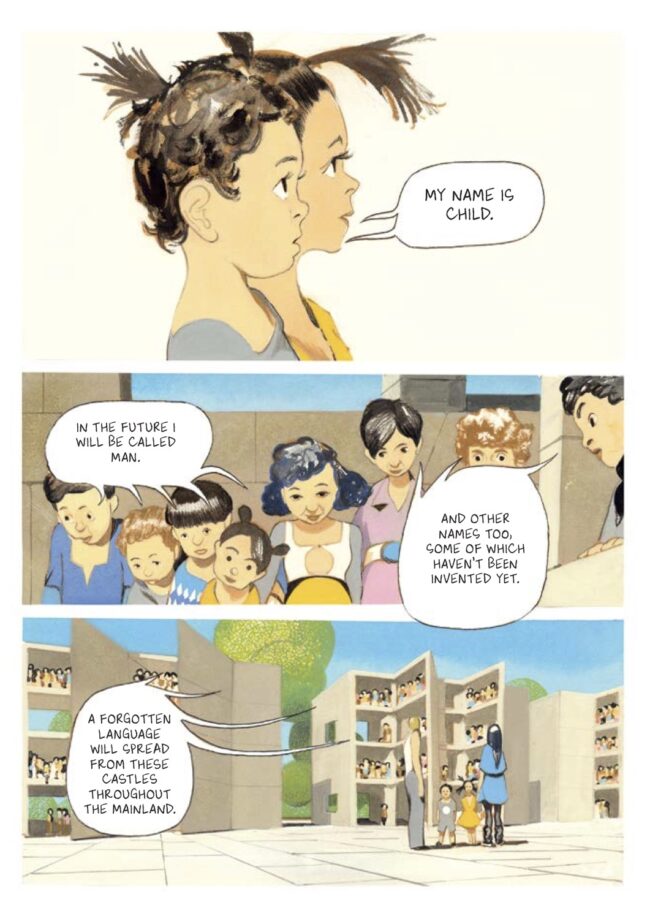

Unfortunately, the beginning of the book is its best part. The art feels vibrant and loose, with dry brush acting as pencil hatching, and shadows taking unexpected colors depending on the mood. The story is yet undefined, allowing the world to be broader and denser than it appears, and the city of Celestia feels strange and familiar at once. Then the book's protagonists, Dora and Pierrot, take their leave, and both the story and the art take a dip (or a bit earlier, around page 42)—the drawings get too polished and enclosed, and sometimes weirdly realistic (especially when children are involved), and the character arc starts following some pretty tired tropes to the letter. You'd come across fantastic compositions and subdued body language in one panel, then something over-acted and almost Disney-ish in the next. All of the paintings are executed masterfully, there's no question there, but the style stops growing, and all the gorgeous vistas begin to feel like too much candy.

And then the journey itself. The story shows us different scenes from the abandoned mainland, but they occupy that uncomfortable middle ground between exposition dumps and total minimalism. It's not a Raymond Roussel-style trek through unexplained strangeness, but it's not a fully-fledged traditional narrative either. The characters come and go, and towards the end we even get a magical unspeaking Black child, who takes Pierrot and Dora home, after serving them a cigarette and having his head petted. The ending is particularly irritating, but I won't spoil it. Let's just say, another trope comes in, quite loudly.

Fior's comics are often about the relationship between two characters, the tension and the back-and-forth, with the setting as a silent third protagonist. It worked best in The Interview, where the two lovers act out the meeting between the old and the new, and the clashing aesthetics of self-driving cars and traditional dinnerware go along with it. Celestia follows in the same general direction, particularly with the architecture—some of the most effective scenes have that aesthetic disconnection, unified by Fior's lines and shapes—but the interplay between the characters is a bit too familiar, and, underneath all the beauty and flair, predictable and at times even banal. Fior's characters are often hinged on one brief moment that decides their lives and leaves them stranded against their will across time and distance, and in Celestia their journey is more literal than ever before. The Interview got away with it through elision and silence—there is so little known about our characters, and they say so little, that they can feel more like conduits to the movements in the air that take place between the panels.

Here, the characters are more fleshed out, and I'm not sure if they benefit from having all those dimensions. The mysterious and elusive Dora of the The Interview is a largely hapless volatile lady sidekick in Celestia, and her companion, the sulky poet Pierrot, is very much your classical prickly bad boy protagonist, who softens in the course of his and Dora's journey, but never quite loses his edge.

For an Italian cartoonist, Manuele Fior is fairly unpervy—his male characters struggle with impotence (an unthinkable concept for Manara & co), and his women don't look like walking portfolios of the author's sexual preferences. It's clear that he feels tenderness towards Dora, but her character in The Interview feels much more real, even in her most vulnerable volatile state. Here she just follows Pierrot, occasionally offering some psychic guidance and flashing her bits a bit too often, and with great detail—page 69 (nice) is a particularly bizarre example of having both the front and back flashed on one page. In The Interview her personality and sexuality were expressed in more nuanced and delicate ways. That book, among other things had an explicit sex scene, that felt much better-timed and more appropriate than the chaste beach affair in Celestia. And the thing about that sex scene in The Interview is that it reads. All beauty and skill aside, there is a real, breathing rhythm to it, and you feel like you're witnessing something as intimate as your own memory. Celestia doesn't quite have that flow. The journey takes many pages, but somehow still feels insubstantial and abrupt, and the inevitable coming together of these protagonists feels unearned.

And that's the biggest problem with Celestia, in my opinion—it's at once too fleshed out, and not fleshed out enough. Fior's strength was never in the words, and there are too many of them here. The book could've been edited down to a much slimmer volume, and I can't help but feel that it would've come out stronger.

I miss the uncertainty of Fior's earlier books, too. Each one was a search, and in 5000 km Per Second, the artistic growth, affected or real, is used as a narrative device (again, intentionally or not is unimportant). Here he's fairly settled in his ways, although later in the book the brush relaxes a little and shows a bit of roughness. Even within this fairly stable style, the panels shift and change their attitude, flatness and finish. I've always preferred Manet's unfinished and abandoned paintings and sketches to his finals—the studies of his that you can find in smaller European museums, away from D'Orsay and whatnot, have so much urgency and personality that can be hard to trace in all the stuff that ended up on screensavers and bathmats—Fior's paintings have that quality, that slight unfinishedness that keeps them moving and alive. I would've loved to see Celestia in a much greater level of undress—to feel the style and narrative search and abandon itself from page to page, as it did in the previous books.

In the end, it's not about the quality of the writing, or the art, and not even about the originality of the characters and the plot—it's about that cohesion that the best comics have and the not-best comics lack, regardless of the excellence of their individual qualities. It's an infuriating thing, since you can't put it in words and formulas—you just feel an absence when it's not there.

Perhaps I'm being too critical here, but I feel that Celestia is a step back. I requested this book expecting to write a gushing review, but the further I got into the story, the more it lost me. I've always admired Fior for reinventing himself with each book, and The Interview in many ways felt like a culmination of his previous themes and explorations. Celestia feels like more of the same, but in color. I hope that whatever Fior does next is completely different, surprising and new. I'd rather read an awful book that takes great risks, than a beautiful and well-paced graphic novel that feels firmly lodged within the author's comfort zone.