The “New Expanded Edition” of Craig Thompson’s Carnet de Voyage uses the occasion of the reissue to allow the author to reframe his earlier narrative. It’s a good use of the device. Sketchbook narratives are odd hybrids that assemble power from being intentionally a little bit of this, a little bit of that – Carnet de Voyage is a sketchbook he kept while traveling across Europe in 2004. It’s a book that chronicles its own creation, usually an interesting process to watch unfold.

Thankfully Thompson is aware of just how problematic his earlier incarnation actually was: “I CRINGE at the character I am on the page,” he says in the new Afterward. “So NAVEL-GAZEY and codependent. My petty whinings are so INSIGNIFICANT compared to what’s going on in the world.” It’s funny, but it’s also true. The Thompson of 2004 was pretty insufferable. I remember 2004. I lived through Blanketsmania. It was A Time, certainly – a time of men and their sad romanticized boyhoods.

Because sketchbooks are already a kind of bricolage, it only makes sense that there’d be another chapter added at some point. It’s useful to understand that Thompson himself has learned something in the intervening years since producing these pages. The reason is that the original Carnet struggles in places against its creator’s youth. It’s no great slander to say that, at not yet thirty, Thompson was a young man. The book is about him beginning the process of growing and up and getting over himself, and its good to know he did, at least a little bit, in the intervening fourteen years.

As a genre travel narratives are both necessary and problematic in equal measure. Necessary because human beings need to understand one another, and anything that bridges those gaps is worthy of celebration. Problematic because there are so many ways to communicate difference in ways that hinder rather than enable understanding. For centuries books very similar to Thompson’s Carnet were able to define the parameters of the non-English speaking world more or less arbitrarily based on poor and often malicious transliterations of cultural practices in one part of the world to another part of the world.

Thompson is aware of this, to the extent that thinking through these problems also became central to Habibi, the book that followed Carnet and inherited from the earlier volume Thompson’s interest in North African culture and design. There’s a Catch-22 here and it’s central to the book and most books like it: young men who go overseas to gain a bit of maturity from a more worldly perspective sometimes learn that real maturity only begins with the insight that other peoples’ countries weren’t created to be backdrops for the musings of sensitive young men.

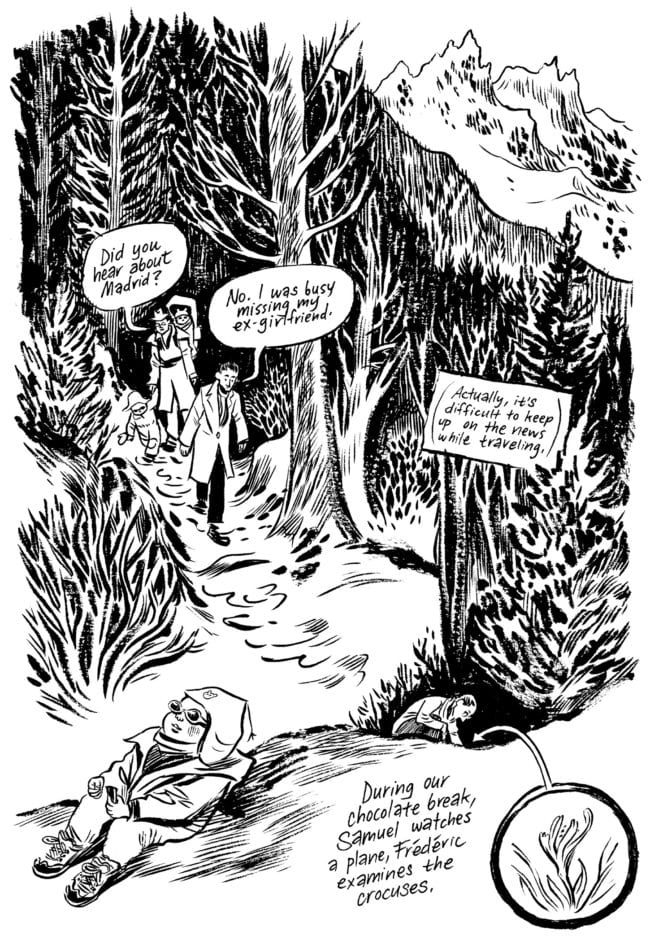

As Thompson points out, he wasn’t even aware of the 11 March 2004 train bombing in Madrid at the time. Turn back to the page in the earlier narrative where Thompson hears about the bombing, while staying the better part of a week at a picturesque chalet near Mont Blanc. His host asks, “did you hear about Madrid?” He responds, “No. I was busy missing my girlfriend.” It was supposed to be funny, and it was, but not perhaps in the way it was intended.

As Thompson points out, he wasn’t even aware of the 11 March 2004 train bombing in Madrid at the time. Turn back to the page in the earlier narrative where Thompson hears about the bombing, while staying the better part of a week at a picturesque chalet near Mont Blanc. His host asks, “did you hear about Madrid?” He responds, “No. I was busy missing my girlfriend.” It was supposed to be funny, and it was, but not perhaps in the way it was intended.

But of course the whole point of cartoonists releasing sketchbooks – any kind of sketchbooks, narrative or no – is the drawing. Thompson can certainly draw. I’ve my issues with the man’s body of work but his books still sit on my shelf, and they sit on my shelf because he knows how to draw really well. I like looking at his drawings even if I struggle sometimes to engage with the solipsism of his earlier material.

That same solipsism gets a bit of a pass in Carnet, if only because the book is already autobiographical. Accusing it of solipsism would be a bit like yelling at fish for getting the carpet wet. As it is, bumming around two continents for a few months does wonders for Thompson. He gets sick, draws a lot of pretty girls, goes snowboarding, rides a camel. Sounds like a fun trip. There are worse ways to get out of your head.

Thompson is a smarter cartoonist than he is writer. If you think that’s a specious distinction when the person doing the writing is the same person doing the drawing, think about how effective Thompson’s sketches are throughout the volume, how expressive and curious and confident his lines are regardless of his tools or medium, and how at odds the technical virtuosity on display is with the lack of confidence expressed in every other element of his narrative. It’s an odd juxtaposition. He knew how to draw but was still a kid in so many ways.

The Thompson who finishes the book isn’t a kid anymore. He understands things like history and context a little bit better, ideas that are present in the original narrative, always pressing in at the corners, but which Thompson hadn’t yet found a way to engage with as things existing independent of their relationship to him. I actually closed the reissue thinking more highly of Thompson for having produced this updated volume, and for understanding that with an added dimension of fourteen years’ hindsight the Carnet has become a different kind of travel narrative altogether: a trip to the past. And the past is a foreign country, don’t y’know – they do things differently there.