Not to suggest anyone outgrows the enticement of getting high, but I believe there is a tendency at a certain point for the world of inner exploration to take a backseat to the challenges of companionship. One becomes resolved to the ineffable and unknowable, and reinvested in the rewards and challenges reality can offer. The world of consciousness may contain depths that can never be sufficiently plumbed, but so too do those close to you, and it’s a far more pressing question how to keep them happy. While there are images to be drawn from the multitude of intensities the brain on drugs conjures up, there are stories to be told about how relationships work. Brian Blomerth’s books may position themselves as ideal gifts for whoever in your orbit is always holding, a brightly colored non-bummer of a trip for people who’d rather just blow a rail of ketamine, but the stories they tell are built on rails of long-term coupledom.

Brian Blomerth’s Mycellium Wassonii follows the married couple Robert Gordon Wasson and his wife Valentina Pavlovna, as Valentina’s Russian upbringing, where wild mushroom foraging is commonplace, gets Wasson interested in different cultures’ relationship to mushrooms, eventually taking the two of them to Mexico to publicize the shamanic usage of psilocybin, or “magic mushrooms,” a phrase Wasson coined. This serves as a companion volume to Blomerth’s previous book, Bicycle Day, which followed Albert Hofmann and his wife Anita as he, working as a chemist, synthesized LSD for the first time. These are books that avoid the narration-heavy style of informational comics to be built around attractive and readable cartooning. Blomerth renders these historical personages as his signature dogfaces, with Valentina wearing a blue and white hat recalling Mickey’s in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, one of the pieces of Disney iconography most popular for blotter acid graphics.

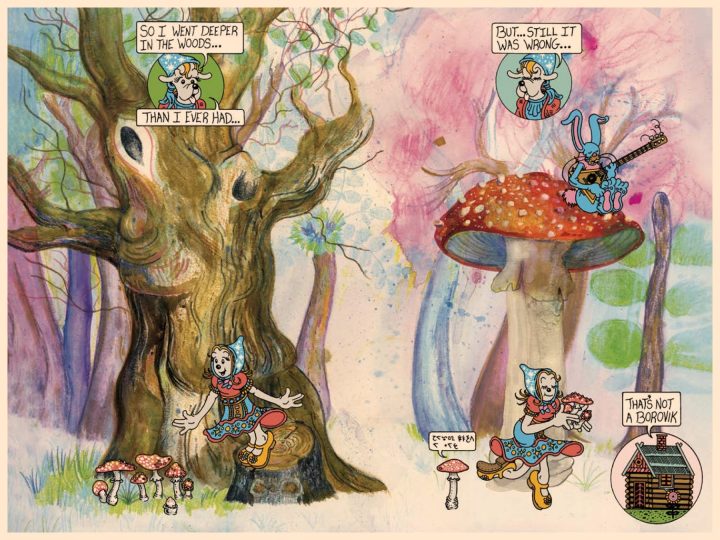

In Blomerth’s hands, the book format made of two-page spreads reinforces the beauty of companionship by way of its own evolving harmonies. Often this takes the form of mirroring, reusing certain compositional elements for elements of page design on facing pages. Slight gradations in style define short sequences. Two pages show the Wassons in the kitchen, accompanied by cookbook instructions. A flashback to Valentina’s childhood utilizes soft colored pencils, with decoration at the edges evoking knit patterns, folk art forms and children’s book styles combining into nostalgic reverie. Life in the city gets depicted in two-page spreads, with characters seeming superimposed in front of detailed backgrounds, in compositions that recall cel animation or side-scrolling video games.

The default palette of vibrant paint-bucket-tool flat color with occasional gradients is supplemented by watercolor painting and textures that might be colored pencils or crayons or both. The organic qualities of these media is in keeping with the emergent properties of mushrooms themselves as living creatures, in contrast to the sharply separate quality of the pantones selected to represent acid hallucinations in Bicycle Day. It always looks great, and introducing these visual approaches in spreads with other examples of the same effect used on the opposite page makes them less jarring than they might be otherwise, the same way that traveling to a far off place, or trying a new food, is eased by the presence of a companion. Plenty of comics introduce media into their visual vocabulary for one-off panels to create a disruptive effect, but Blomerth is working within a tradition that prizes readability, and his stylistic excursions are integrated seamlessly.

It’s clearly a well-researched book, but there’s no dumps of expository text. The research was done in service of finding things that work visually. There aren’t jokes told in dialogue to spice things up, any inherent humor is built on storytelling based in the ironies and oddities of the historical record. The drug trip sequence, with its obvious opportunities for visual spectacle, is actually a very small part of the book. Blomerth’s skill as a storyteller becomes evident when interesting details of dovetailing history, like the CIA trying to fund the Wassons, are enlivened with bits of visual business to keep pace with the more showstopping blowouts.

The inscrutable mystery of mushrooms themselves is taken seriously by various visual schema. This manifests in ways uniquely cartoony — the invention of an encrypted “mushroom language” of glyphs in tiny word balloons littering the edges of certain pages, possibly making jokes, but beyond my skillset to decode — and classically field guide. An early sequence, announced with inksplattered lettering as “Mushrooms of the Catskills” takes pains to delineate a bunch of little guys such that they can be distinguished from one another with accuracy in real life. This happens as a backdrop to an important part of the characters’ story: It’s on their honeymoon that Wasson’s reconciliation to the mushroom takes place, and the story of the marriage that follows proceeds from that point. A handful of psilocybin mushrooms might taste like dirt, but Mycellium Wassonii is quite sweet.