This is absolutely the damnedest book of 2020 - like a mad exaggeration of what 'graphic novels' are now expected to be. Amidst the scores of trim bio-comics of political and historical figures, fit for the shelves of any major bookstore, comes a one thousand, three hundred and eighty-four page imagining of the life of the man who shot John Wilkes Booth, lashed with mystic and oneiric elements, sliced into three square-shaped softcover books and stuffed into a slipcase. It's as heavy as a child's bowling ball, it comes with a link to an official soundtrack -- you are prompted as to which tracks to play by small symbols on the edge of certain pages -- and sells for the worryingly low price of thirty dollars. As far as I can tell, the artist, Andy Douglas Day, has only ever done two interviews: one with Margot Ferrick that is no longer online; and another with August Lipp in issue #2 of But is it... Comic Aht?, which is where I first heard of him. From these discussions, we learn that Day did not begin drawing comics until his late 20s, and only then as a result of a thyroidal condition, by which eating ice cream gave him an intense and frantic energy; ice cream indeed occupies a certain totemic significance in this book. Day is not apparently a great reader of comics, admitting familiarity just with daily newspaper strips and the art he would see on Tumblr, from when that platform had a bustling alternative cartooning scene. Boston Corbett was supposed to be posted on Tumblr, but is instead a book. Sonatina has published all of Day's print-format solo comics: Chauncey (2013); Miss Hennipin (2014); and this. He works a job outside of comics, and appears to approach cartooning as part of the process of life, rather than as a career-focused endeavor.

Day also mentions starting work on Boston Corbett having only read a Wikipedia article on the historical figure, which is the kind of thing people usually say to insult bio-graphic novels, although here it works firmly to the advantage of a comic that is perpetually in a state of flux. While ostensibly spanning more than half a century's events, the book's chapters -- ranging from 2 to over 100 pages in length -- do not always appear in chronological order, nor do all of them even occur within the human perception of time; one major character is a sort of cosmic craftsman of boutique slumber who ascertains human existence not unlike the reader hovering over the book: as a series of frozen moments, easily navigable. At one point, this character transforms their body, possibly for some esoteric procedural reason, or possibly because Day simply decided to draw them in a different manner. And, for the first few hundred pages, this can be a challenging book to 'follow' in the narrative sense - I would suggest honing in on certain distinguishing features of the characters, particularly their noses, as a means of following them chapter-by-chapter (or even page-by-page), as Day does not always maintain the consistency of depiction typically expected of what otherwise functions as a literal storytelling comic.

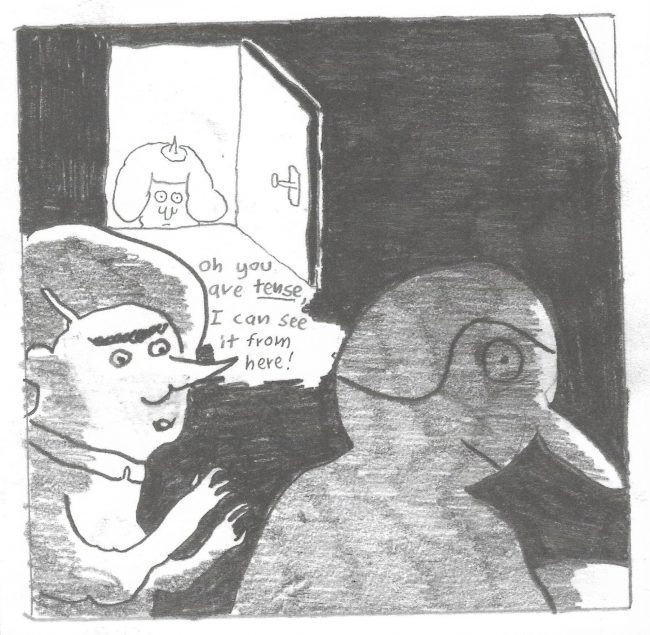

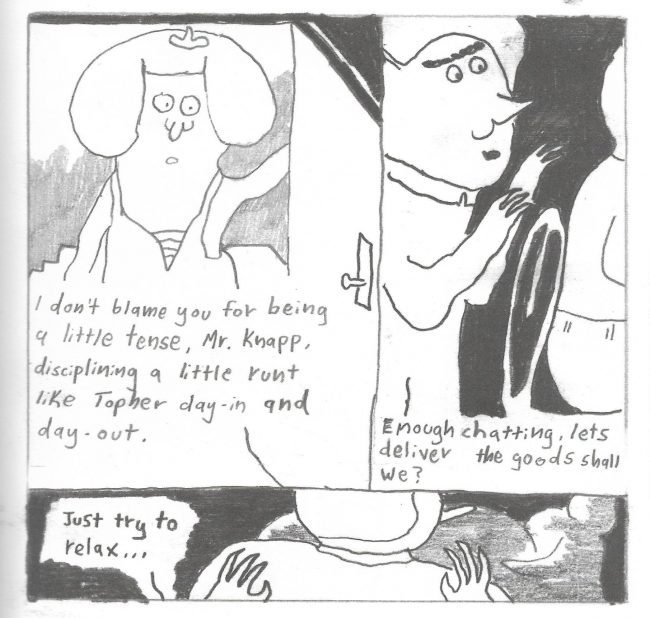

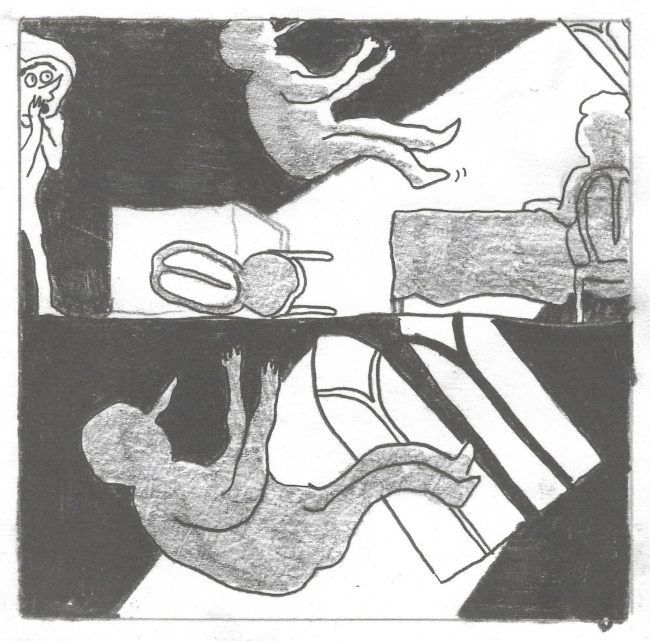

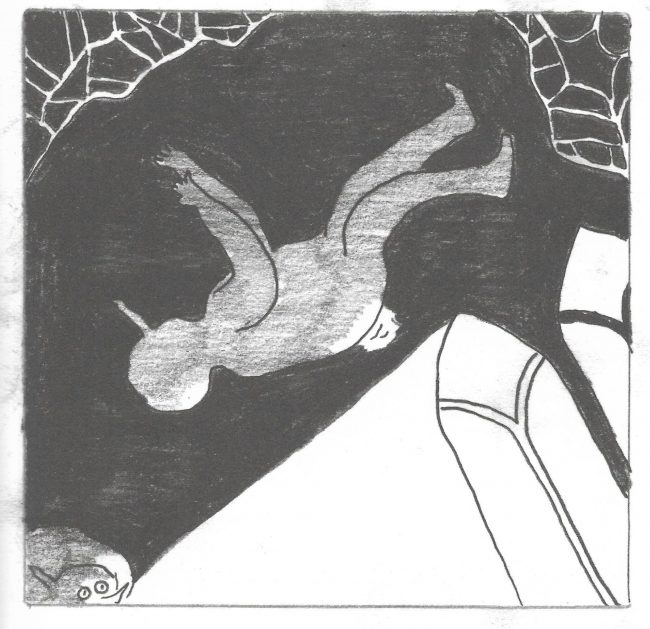

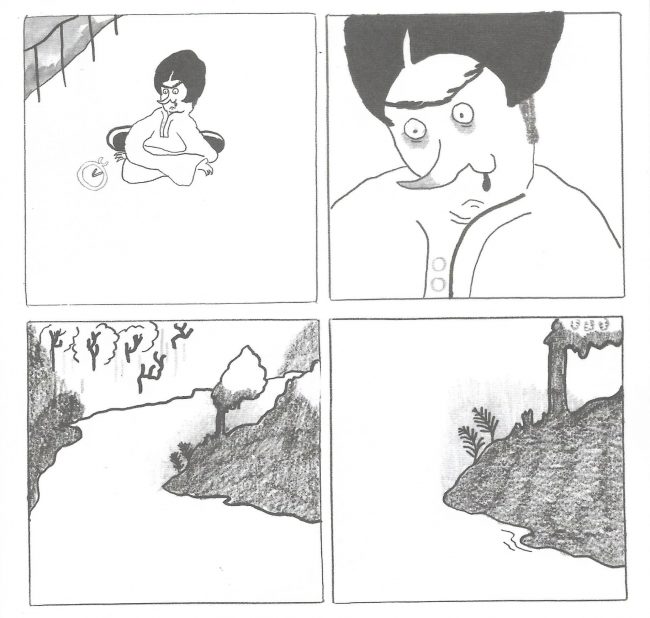

Yet this promiscuity of style -- pen and pencil, lines and washes and smears at differing resolutions, drawings made at different sizes, page by page -- has a way of capturing the uncanny:

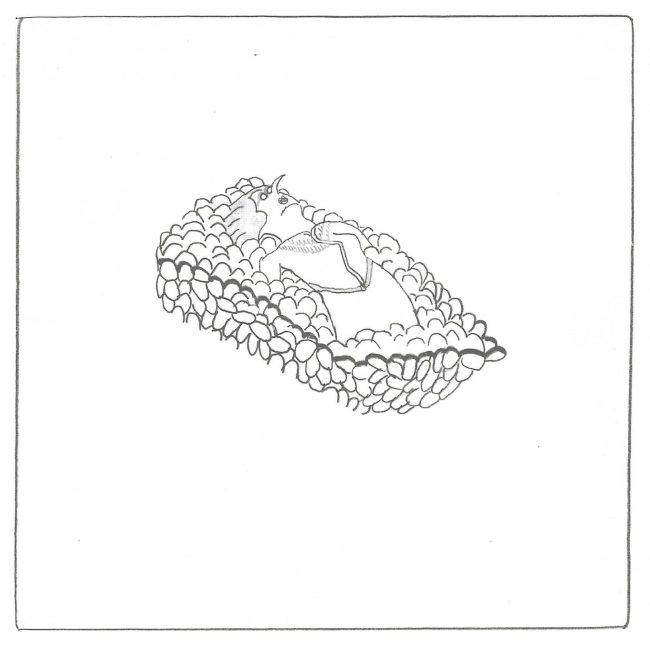

The real Thomas "Boston" Corbett -- a hatter by trade given to religious zealotry so all-consuming that he castrated himself with a pair of scissors to relive himself of sexual temptation, and who insisted, to no small acclaim, that God had directed his action in the killing of Booth -- begs an approach to his story that dispenses with the simple facts of perception to encompass a visceral metaphysics. What Day does is set up his chapters, almost always, as exchanges between two characters who are 'close' in some way, but don't entirely understand one another. This includes Corbett and the various companions throughout his life, but also a pair of Union soldiers on the hunt for Booth; a talking Tortoise and their lover, a Boulder; a pair of mysterious ladies in a skull house discussing transcendental consumer experiences; and, in a 300-page outro set mostly in the 1990s, an anxious small-time classical musician and his supercilious pal. The give-and-take of these characters serves to emphasize their quixotic fascinations.

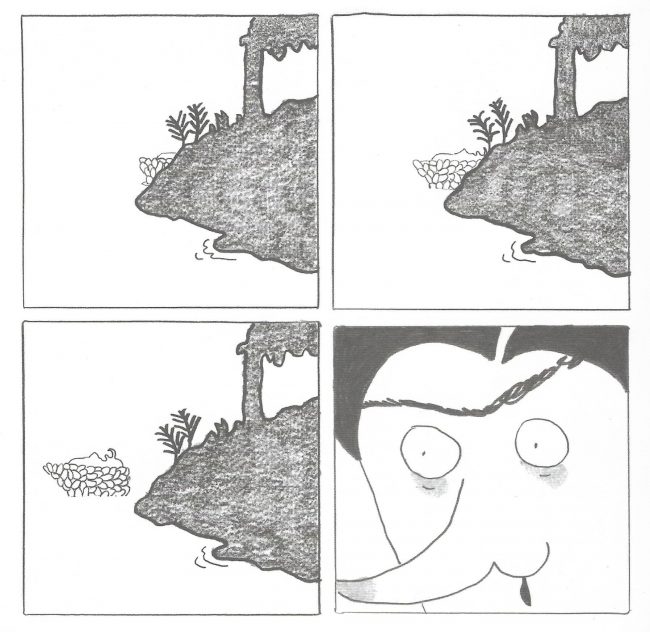

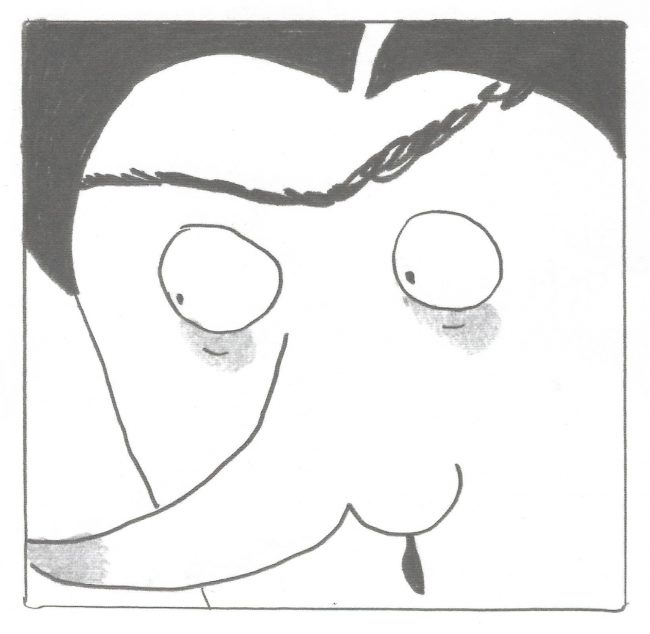

Perhaps the Tortoise and the Boulder are having a picnic, and they need to get some caviar; a nearby dolphin friend, Goldie, has eaten all the fish in the lake, so they throw her a birthday party with a cake covered with poison berries that will cause her to vomit up all the fish. She later develops cancer, and the Tortoise worries that it was the berries that caused it. Or, Stuart and Whit, the Union soldiers, are deep into their surveillance of the area to where Booth may have escaped. Whit decides to take a dip in a very tiny stream, and promises to bring Stuart back a cool rock; but, when he has returned, Stuart has sunk so deep into his hood that Whit can no longer see his face. He drops the cool rock into Stuart's hood, and it comes out split in half, revealing crystals inside. Or, Corbett, the acclaimed hatter, has been summoned to Saugus, MA to meet with an eccentric client who wants Corbett to design a hat to disguise an absolutely massive growth on his head. The two wind up discussing what 'sex' is, and subsequently take a trip on a riverboat, which ends in calamity as Corbett is overcome with one of his perpetual erotic-grotesque visions of willing or ready or supine women, which he associates forever with temptation:

And yet, while the geography is never exactly clear, a portion of the boat on which Corbett is riding will be seen capsized in the lake occupied by the Tortoise and the Boulder, as a blessed gift of their god, the Wettest One. So too will the split crystal rock held by Whit, which the Boulder will consult as a sort of radio. The poison berries on the cake are visible on the bushes surrounding Stuart and Whit. Later, in the 1990s, Dabbler, the anxious musician, will embody several prior characters. When the water blast of a shower head hits his neck, it will recall the gunshot that killed John Wilkes Booth. When he cuts off the phallic neck of a special shampoo, it recalls Corbett's self-castration. But he will never notice this, of course; he is concerned about the state of his wiry hair, and of appearing cultured, so that maybe he will impress somebody who will then love him. He is like Corbett, but his sexual neurosis is much smaller, and his world lacks the communion with the Divine that marked Corbett's age. Meanwhile, outside of time, two ladies give a tour of their fine household goods, which distinctly resemble characters and events from the rest of the book, reduced to cute gadgets.

By this point, I was convinced that Boston Corbett needed to be 1,384 pages, because Day is fundamentally addressing the providential outlook of the historical Corbett. His obsessions with religious purity are the most frequent of the preoccupations highlighted in the book's one-on-one exchanges, but Corbett’s is fundamentally a misapprehension of the real state of things. As a child, Day's Corbett meets with a masked police officer who treats him and his troubled chum Topher to a local milk bar. This adventure, if you so choose, can be set to the soundtrack by Portland's Hacienda Bridge House Band, which frankly reminds me of some of the eerier samples-and-synths stuff you'd hear on Hearts of Space or Philadelphia's ambient radio institution Echoes, rather than anything relevant to the mid-19th century - but Day is likewise unconcerned with historical accuracy. On the fantasy plane of his 1842, milk bars offer creamtop pours with men's wallets hidden inside, and whirling whips that leap from the glass, the jagged peak of their splash anticipating the licks of flame that will consume Corbett's life during the Great Hinckley Fire of 1894. Time is both immense and immediate. Women are predominantly either adversaries or terrifying mysteries. Children are at the mercy of adult authority, which they do not understand, and Corbett indeed will continue to be at the mercy of Eyeoda, the aforementioned sleep salesman from outside of the chronology, who pops into the man's life every so often to manufacture the trajectory of Corbett's historical role (and indeed, that of the United States of America) for his own completely ridiculous consumer missions. If he cares about what his actions mean for anybody other than his clients, he doesn't let on.

But I don't think you're immediately supposed to notice any of that; certainly no more than the characters do. Miss Hennipin was similarly a work of dialogues, but its was a dense construction; here, enough of Day's pages are single images that the book's pace is very swift, save for when it wants you to pay a bit of attention to the conversations. There are *so many* conversations in this very long book, that you only faintly become aware of the controlling forces behind all of the action as time rushes by. It's like life: talking, talking, doing things, chasing small obsessions, believing yourself a figure of great interest to God, but what is really happening is that you're subject to the capricious desires of equally silly people who happen to occupy a higher economic/social/cosmic plane than yourself - your fixations, like those of Day's characters, manufacture systems of control that helpfully draw attention away from what might actually be happening, which is both stupider and more serious than expected. And you will spend a long time in this book chasing obsessions, perhaps fondly. The artist does not judge.

Of course, reading this book as only a tale of capitalism -- of a technocratic elite sitting in the position of gods -- probably reduces it. This is, after all, a story set in the U.S. Civil War era that does not particularly concern itself with ideas of race, or the specifics of human bondage; I don't think assessing it as a political statement does it many favors. Boston Corbett is just as easily an obscure mystic fable, or a burlesque of religious devotion, planted within the absurdities of a sort of timeless contemporaneity. Yet in its obscurity, comes the beguiling and slippery aesthetic that is the murmur of the subconscious, divined by an improvisational approach to narrative; Day's whimsy is the sort that speaks to amusement as a premium. He has said that he does not revise his drawings, though sometimes he will draw things again from scratch. It is unbelievable and superb that this book exists as it does - like a twee festival minicomic, whispered about from attendee to attendee, writ as large as you can possible imagine and stretched to address the stars. For a moment, you believe again that anything can happen in alternative comics.