What would happen if our government banned self-publishing? I mean, it’s easy to imagine a world where the government attempts to restrict or censor internet content—in part because we currently live in that world—but printed works? Come on now. So when French Parliament outlaws self-publishing in Pierre Maurel’s dystopian Blackbird, it’s a reminder of a time—at least in the U.S.—when published material was actually thought to be a weapon of influence. Think the 1973 Supreme Court ruling on obscenity that lead to censorship of underground comics, or the era of The Comics Code Authority. The printer mightier than the sword, as it were. The imagined world in Blackbird is simultaneously sentimental and dismal as it reminds us of the potential power of small, independently-produced works, but then ultimately shows us how easily the government can extinguish that power. I fear that this book will come and go without the props or the critique it deserves.

Blackbird is a Conundrum International spring release for 2016. It was originally written in French, self-published by Maurel in six issues between 2009 and 2011, and sold exclusively online. The collected issues were first published in 2011 by Belgian publishers l’Employé du Moi, an indie comics press based in Brussels. This is the second of Maurel’s books to be translated into English. As a point of clarification, “Blackbird” is both the title of the book and a fictional zine within the narrative. Maurel’s original six issues are sometimes referred to as “zines,” a term which is interchangeable with minicomics in Europe. But Blackbird was never a zine in real life—not in the way we think of them in the U.S., and not in the way it exists within the narrative.

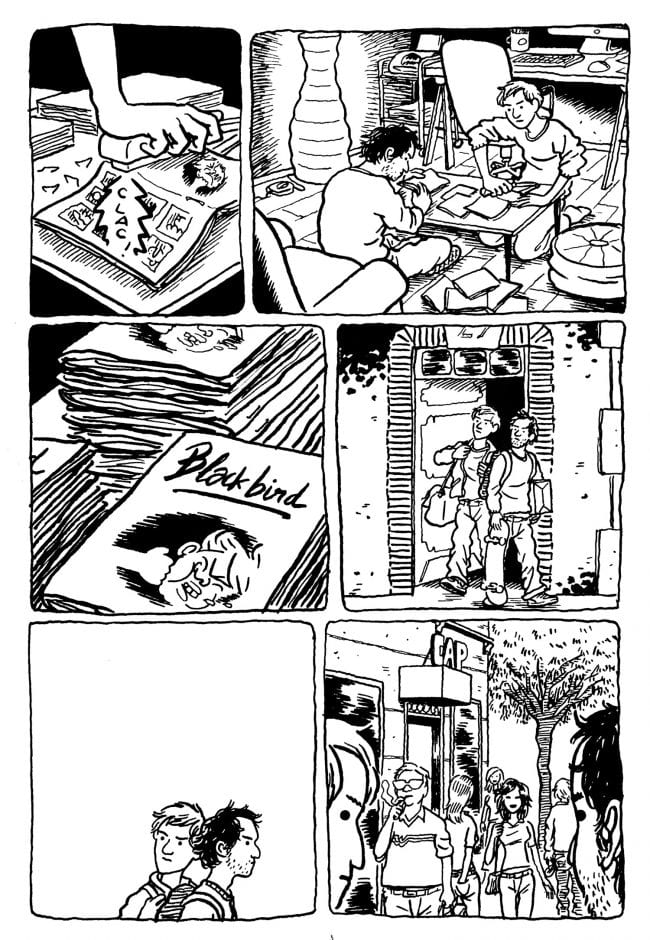

The book Blackbird follows a group of friends—young anarchist skateboarders in France who together produce the zine, “Blackbird.” Four guys, and one girl. They remain somewhat anonymized to the reader throughout the book as no character is referred to by name. By consensus, the group agrees on the format and content—which is vaguely described as being “all about their lives”—for each issue. Before the restrictive legislation, they would print the zine at local copy centers, and together they would assemble and staple it at their squatted headquarters. Then, they would distribute issues to local book shops and record stores, usually leaving only three copies at a time. Not a massive or efficient effort, but a personalized one. One that relies on community support, and relationships between individuals.

The new law ruins all of this. It effectively bans self-publishing by requiring all content to be managed by “certified” publishers that work through mass channels of distribution. Purportedly, this new measure would “improve distribution and remove contentious content,” but that’s just legal jargon for censorship. Any shop that continued to sell self-published materials would be fined or even shut down, so Blackbird loses their distribution instantly. “I don’t get it. Don’t they see what’s happening? I mean, what’s next?” says one of the zinesters in response to this.

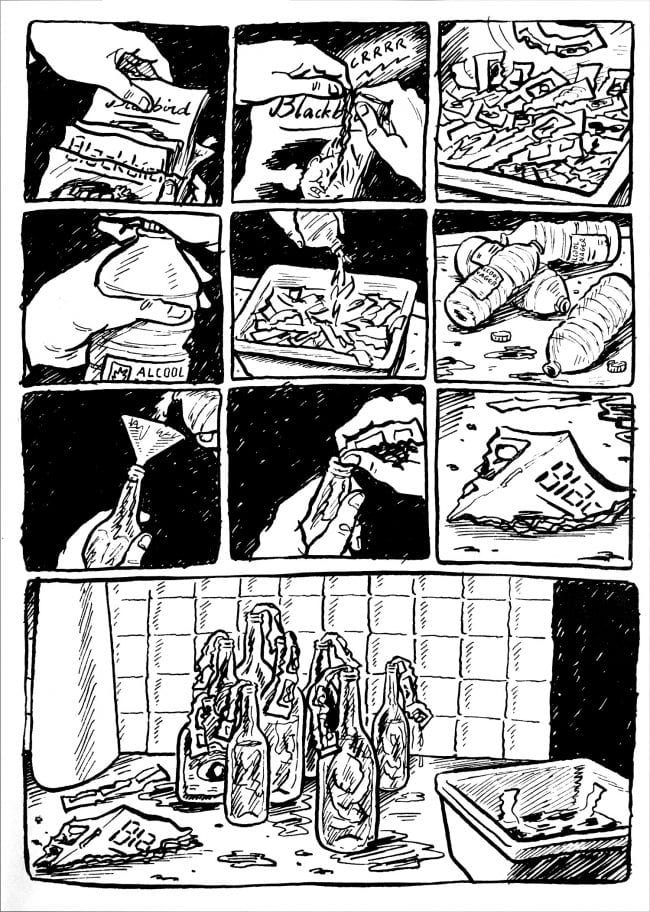

Fear inspires divergent coping methods for the zinesters as they attempt to circumnavigate the new legislation. As a result, the group splinters. One zinester quits self-publishing entirely and signs with a big publishing house. Another commits a violent crime and goes into hiding. Two members covertly acquire a copy machine, thereby owning the means of their newly-underground production. Curiously, the female zinester does nothing except perform a supportive girlfriend role to one of the men (insert side eye). Unfortunately, the police connect the “fringe group of self-publishing radicals” with the violent crime. They raid the squat, confiscate the zines, and subpoena the members for assault and unauthorized publishing. At that point all five members are forced into hiding.

There are flecks of wry humor throughout the book, most notably when one anarchist’s ringtone embarrasses him in front of a hot girl. Huey Lewis’s “The Power of Love” blares from his cellphone and unwittingly induces nostalgia for an early scene in the '80s sci-fi comedy Back to the Future. (You know, the one where Michael J. Fox skateboards to school?) Elsewhere, Maurel’s characters make droll remarks about the pointlessness of publications without images, or the influx of blog culture. Maurel’s brand of levity balances the darker parts of the book, like in the last chapter when they launch Molotov cocktails into government vehicles. The book is equal parts Man in the High Castle and Back to the Future. “Dystopia-lite.”

Maurel crafts beautiful temporal layering throughout the book, increasing the visual gutsiness with each chapter, and breaking out of the six-panel-page comfort zone he establishes early on. His inky drawings are beautifully spare, and especially impressive since he didn’t use photographic reference for any of the artwork. There is a filmic quality to his storytelling, as he renders the cartoon equivalents of screen dissolves, stage lighting, cross-cutting, voiceovers, and flashbacks. His drawings of skateboarding sequences are Muybridge-like. As for the book itself—although understated, it’s perfectly designed for the story within. The cover has a no gloss, DIY-style chipboard surface, the kind that will show it’s wear within seconds of handling. The ink is powerfully simple—red and black. Even as a 128-page book, it retains the intimacy and allure of the self-published minicomic or zine.

The narrative takes an exciting turn when remaining members of the group begin direct actions against perpetrators of the restrictive publishing law. They confront MPs (members of parliament), and demand to know the real motivations behind the legislation. As soon as these confrontations escalate, one zinester sprays an offending politician with ink as another video records, and later posts on YouTube. They create a new issue—the first illegal issue—of Blackbird using stolen paper and toner. Featuring a cover of “fight the power” fists, the zine is freely distributed throughout the city at bus stops, park benches, or wherever they can reach people outside of normal or “legal” channels.

The spirit of these actions harkens back to the work of French autonomist groups of the 1970s, like Action directe or Os Cangaceiros, who carried out attacks against police, politicians, and the military. In fact, it was the direct actions of the Tarnac Nine, the anarchist group who in 2008 disabled over 160 trains in the french rail network, that provided inspiration for Maurel’s narrative. Because of this anarchist influence, it seems ridiculously incorrect that the Blackbird crew would use a tactical channel like YouTube, which is owned by the notoriously neoliberal, data-collecting company, Google. It’s quite a contradiction with the group’s earlier, community-based approach to content distribution.

The fact that the story deals primarily with government restriction on printed materials—i.e., objects and not information—makes the story seem anachronistic, a little passé. Truthfully, I’m nostalgic for a time when something like this could happen, so I don’t mind the anachronism. I miss the days when Tipper Gore or Jesse Helms were the “bad guys” of censorship. Their anxieties about rap music or NEA-funded artwork just confirmed the power it had. Now, censorship resides in more covert territory—government-sponsored internet trolls that may or may not be controlling our content. So in this way the story seems a little naive for contemporary readers.

Overall, what Blackbird offers is rare in comics narratives, and it’d be great to see more of this kind of storytelling in the near future. It’s a sci-fi comic, but it isn't as complex as Monstress or Saga, and it doesn’t spend a lot of time developing metaphorical future scenarios, otherworldly characters, or fictional languages. Instead, it makes a brief, concise, and unmistakable statement using recognizable characters and structures of power. It says, “Look, you guys. This could actually happen, and maybe we’re one unjust legislation away from chaos.” It’s a great sci-fi read for non-sci-fi people. And even though the story resonates broadly and politically, it’s possible that for Maurel, Blackbird is a more personal story than that. Admittedly, he prefers the hands-on process of self-publishing—the copying, the folding, and the stapling—and the personal relationships that result from it. He loves the object-ness of the comics he creates. He considers all the details, and this is obvious when you read the book. So, it could be that Blackbird is really Maurel’s personal dystopia—a world where he couldn’t create and distribute his own comics. What first appears to be a cautionary tale about censorship, could actually be a romantic ode to self-publishing.