In a recent interview with Tom Spurgeon at The Comics Reporter, cartoonist Mike Dawson talked about the trouble he had coming up with an “elevator pitch” for his new graphic novel, Angie Bongiolatti. This absorbing, smart, character-driven book is hard to sum up—to its credit. Unlike some recently published books touted as "graphic novels” that are really longish short stories or novellas (such as Lille Carré’s excellent The Lagoon) or extended riffs on a theme (such as Corinne Mucha’s Get Over It), Angie Bongiolatti is truly novelistic. It has scope, depth, complexity of character and action, and it’s rendered in Dawson’s typically gorgeous, densely detailed but crisp graphics. (The pitch Dawson finally settled on: “It’s about politics and sex.”)

Angie Bongiolatti follows a group of twenty-something New Yorkers in 2002, most of whom work at an "e-learning" start-up, as they confront, explore, argue over, and try on for size an array of personal and political belief systems, credos, and values. Dawson juxtaposes the group’s groping-for-answers with illustrated excerpts from the writings of Arthur Koestler, a Hungarian-British writer and journalist with a very definitive worldview. In one manifesto Koestler states: "there is little difference between a revolutionary and a traditionalist faith… all true faith is uncompromising, radical, purist." He paints true faith in absolute opposition to the status quo. Angie Bongiolatti, the still center of this motley crew, seems to embody this statement.

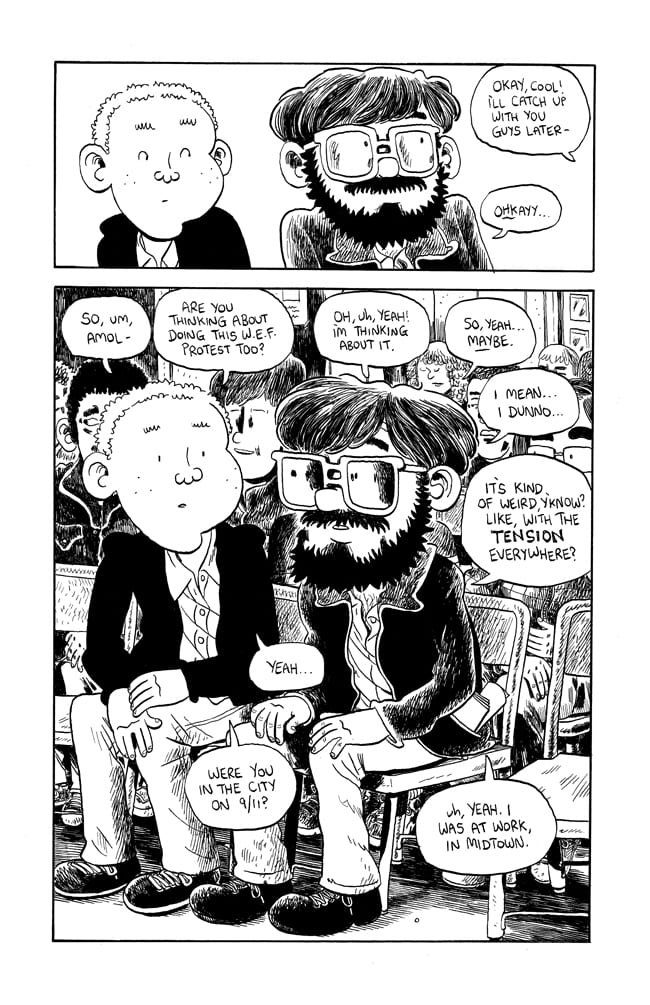

In the post-9/11 landscape, the world pretty much went insane. It was a bewildering, politically and socially fraught time. For young adults trying to launch their lives and careers post-college, it must have been especially daunting. Dawson deftly captures the struggles of this era through his cast's alternately bewildered, hopeful, cynical, nihilistic, or apathetic eyes.

Of them all, Angie seems to have the clearest political vision, working tirelessly to affect change through her activism. In contrast, there’s the apolitical-but-trying-not-to-be Matt, slave-to-pop-culture hipster Malcolm, and insecure Amol, unemployed after the one-two punch of the dotcom bust and 9/11, who fills his days writing comedy scripts with a pair of friends, hoping to hit pay dirt. Angie’s middle-aged supervisor Jon is burned-out, cynical, seemingly long past any youthful idealism, unhappily-married with an exhausted wife and a newborn baby. There’s also ultra-radical, hardcore Kim, Jon’s mirror opposite, who sees so much injustice and selfishness that she’s ultimately reduced to a sort of nihilism. Arguing with Angie’s latest Fight the Power exhortations, Kim sneers: “No. That’s all just fantasy. That’s some bullshit you tell yourself to preserve optimism…nobody cares about your organizing-for-action, activist bullshit. None of it matters.” To Kim, Angie’s “cushy” job at the e-learning outfit marks her as participating in—thus ultimately supporting—the status quo. But she's not too proud to let Angie buy her lunch, either.

Though Angie acts as a sort of barometer for all of the other characters’ feelings about personal politics, she herself remains rather enigmatic. We never really get inside her head. Politically, she’s a leftist. In her personal life she's a sexual libertine, who enjoys with her partner Steve luring other men into three-ways (in fact, it’s her reputation for sexual shenanigans that attracts Matt, Malcolm, and Amol into her orbit). This free-and-easy approach to sex might be fun for Angie and Steve, but they don’t much consider the feelings of their playmates. Does this experimentation have a political dimension? Are they just trying to hold on to their free and easy college days? These romps actually come across a tad on the creepy side. As passionate as Angie is in discussions of economic justice or the very narrow differences between Democrats and Republicans, in sexual matters she's aloof. She and Steve never discuss their roundelays honestly or intimately; once climax is reached their guests are casually dismissed, without fanfare. The sexual arena can be as messy and inequitable as that of politics.

In politically anxious times, even the apathetic are stirred, somewhat. Matt and Amol both attend a rally to protest a meeting of the World Economic Forum (an international gathering of fat cat billionaires), but each is there almost entirely out of desire to impress Angie. When Matt says, “Things should really be different, right? Don’t you think?” he speaks for the many who believe in “change” in the abstract but have absolutely no concrete plans (or real desire) to personally do anything to facilitate it. Contrast this with Kim, who has very black-and-white beliefs in a world filled with ambiguities and mitigating factors. But it’s unclear what action Kim has in mind either: it’s hard to act at all when pretty much any action will compromise some cherished value or other. Angie seems to have a really clear sense of What Needs To Be Done—politically, if not personally—while others stare glassy-eyed or paralyzed into the political whirlwind, putting self-interest or self-preservation first.

In the end, despite the fact that most of the employees of the e-learning start-up are laid off, Angie remains undaunted: “The basic concept,” she says, “of making education more accessible. That’s noble.” Her faith in the rightness of a cause—even e-learning—will carry her forward.

The novel comes together much like real life, complicated and ambiguous, with no easy answers given. In the previously mentioned interview, Dawson briefly discusses his work process and states that he works around core ideas, eschewing tight scripting, finding inspiration and improvisation through drawing. He captures New York City in all of its grimy, crowded glory, and delineates his characters through razor-sharp background detail (one look at Malcolm’s cluttered apartment, with wadded up tissues strewn on the floor next to a bottle of lube and a Fangoria magazine, a Pulp Fiction poster on the wall and bookshelves full of underground movies and VHS porn, telegraphs all we need to know about him). Dawson’s characters would be archetypes except that he fleshes them out them so vividly. I’m pretty sure I’ve met all of these people in real life, argued with them, partied with them, worked alongside them. Through them, Dawson captures truths about what it is to be young and free, with an intimidating world of possibilities stretching out into a possibly exciting but also quite possibly disappointing, or even terrifying, future. Conceived and executed with acute anthropological detail, rich in ideas and sure to inspire discussions, Angie Bongiolatti illustrates the complex space between the personal and the political.