All the Answers documents Michael Kupperman’s efforts to learn more about the years his father, Joel Kupperman, spent as a child performer on Quiz Kids, first a radio game show and later an early television program. Throughout the book, he contends with both the hastening of his father’s dementia and a reticence about Quiz Kids that predates that diagnosis. The program had been a "forbidden subject” during Kupperman’s own childhood, and he devotes much of All the Answers to exploring how the experience might have damaged his father. This means also turning toward a curious intersection in US history.

Early in All the Answers, Kupperman looks at the concept of the child prodigy and its rise in popularity during the first half of twentieth century. As waves of immigrant families arrived in the United States, a prodigy in the family meant a possible shortcut to upward mobility. Kupperman’s father, who came of age in the 1940s, grew to see himself as having been groomed for the role. Although he did indeed have an exceptional talent for math, there were other forces at work.

The book describes Quiz Kids creator Louis Cowan’s plan to combat World War II-era anti-Semitism by spotlighting gifted Jewish youths, even taking them on tour. “So was my father propaganda?” Kupperman asks. “I now think he was.” All the Answers suggests a measure of success for Cowan and Quiz Kids, but at the expense of Joel Kupperman’s childhood. “By 1943, he was receiving 10,000 pieces of fan mail a week,” Kupperman writes. “He was soon the most famous prodigy in America.”

In its gravity, scope, and personal focus, All the Answers marks a major departure for Kupperman, best known for absurdist humor comics such as Tales Designed to Thrizzle. And yet fans of those comics may still find much to like in Answers. Kupperman arrives at a variety of surreal images, such as a row of Quiz Kids participants in graduation gowns, waiting to be heard across the nation. The strangeness of Joel Kupperman’s youth often defies belief; he meets Orson Welles at one point and has no patience for Welles’s magic tricks. Kupperman’s talent for the bizarre is especially useful during a sequence in which a ghoulish Henry Ford—“trying to repair his image by reversing his stance on Jews”—stops by a hotel room Joel is occupying with his parents, keen to speak with the boy.

In its gravity, scope, and personal focus, All the Answers marks a major departure for Kupperman, best known for absurdist humor comics such as Tales Designed to Thrizzle. And yet fans of those comics may still find much to like in Answers. Kupperman arrives at a variety of surreal images, such as a row of Quiz Kids participants in graduation gowns, waiting to be heard across the nation. The strangeness of Joel Kupperman’s youth often defies belief; he meets Orson Welles at one point and has no patience for Welles’s magic tricks. Kupperman’s talent for the bizarre is especially useful during a sequence in which a ghoulish Henry Ford—“trying to repair his image by reversing his stance on Jews”—stops by a hotel room Joel is occupying with his parents, keen to speak with the boy.

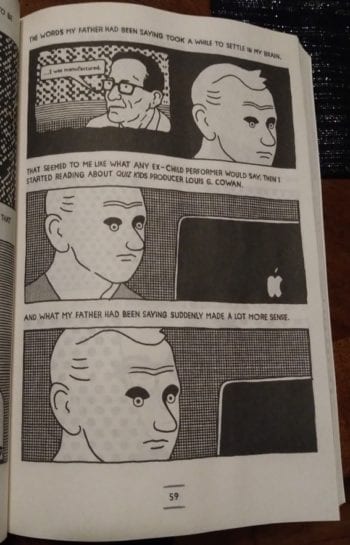

Answers includes a more limited selection of formal flourishes than a reader would find in a Thrizzle collection. This is a more restrained Michael Kupperman. Most pages feature two or three tiers of wide panels, with Kupperman’s narration atop them. Within these pages, Kupperman often concentrates on a fixed image, zooming in or out down the panels. The effect is something like a comics version of a Ken Burns documentary, with mixed results.

On some pages in which Kupperman repeats the same image, the second and third panels come across as a perfunctory, there to accompany lines of prose. Other pages benefit from the zoom. One depicts the Xerox of an autobiography that Joel Kupperman abandoned, shown larger in three successive panels—not one of the book’s most dynamic layouts, but one that manages to position the elder Kupperman's manuscript as if it were the Ark of the Covenant. With the best of these pages, the layouts function like the architecture of the reader’s experience, guiding our motions, moods, and pace.

On some pages in which Kupperman repeats the same image, the second and third panels come across as a perfunctory, there to accompany lines of prose. Other pages benefit from the zoom. One depicts the Xerox of an autobiography that Joel Kupperman abandoned, shown larger in three successive panels—not one of the book’s most dynamic layouts, but one that manages to position the elder Kupperman's manuscript as if it were the Ark of the Covenant. With the best of these pages, the layouts function like the architecture of the reader’s experience, guiding our motions, moods, and pace.

Kupperman’s line is thick throughout the book, and his compositions are typically heavy on blacks, selective about detail, and big on patterns. The exigencies of drawing a 200-plus-page book might have partially informed this approach, but Kupperman’s choices tend to work on their own terms, annexing the memoir’s historical elements within his subjectivity. Many pages feature dotted backgrounds in lieu of a specific environment, and often these patterns help convey a moment’s ambient anxiety—they’re a fixture of scenes in which Kupperman asks his father difficult questions, for instance. (In this way, the dots are also a reminder that this book is one person's version of another person’s experience, not some objective text.)

Kupperman’s renderings of his father and himself are among the book’s most notable visuals, emphasizing the contrasts between the two men. Kupperman draws himself as a man adrift, with tiny, rounded eyes and a wrinkled brow. If the book were a Hanna-Barbera cartoon, he’d have just swallowed a scientist’s confusion potion. His father meanwhile sports square, wide eyeglass frames that confer an authority—even a kind of fortification—that the son doesn’t have.

As a narrator, Kupperman’s tone is cool and at times almost journalistic, which gives the book’s harsher pages a kind of blunt force. In one sequence, he recounts his father being bullied in college by peers who grew up resenting Joel Kupperman the public figure. Joel is stripped to his underwear and covered in food by the sequence’s end. Kupperman doesn’t have to sensationalize this; choosing not to look away is enough. The same goes for some formative moments between the father and son. “A memory from the early ’70s” finds the two of them in a swimming pool, with Kupperman asking his father, “Daddy, do you love me?” The answer leaves the young Michael alone and expressionless, floating in a pool of dots.

As a narrator, Kupperman’s tone is cool and at times almost journalistic, which gives the book’s harsher pages a kind of blunt force. In one sequence, he recounts his father being bullied in college by peers who grew up resenting Joel Kupperman the public figure. Joel is stripped to his underwear and covered in food by the sequence’s end. Kupperman doesn’t have to sensationalize this; choosing not to look away is enough. The same goes for some formative moments between the father and son. “A memory from the early ’70s” finds the two of them in a swimming pool, with Kupperman asking his father, “Daddy, do you love me?” The answer leaves the young Michael alone and expressionless, floating in a pool of dots.

With pages like this, All the Answers becomes a brave piece of storytelling—not only because of Kupperman’s willingness to depart from humor cartooning but also because of his willingness to contemplate not being consistently or adequately loved. The examination of how fame traumatized his father extends to how that trauma affected his father as a parent. And although Kupperman is not shy about listing his father’s shortcomings, the book avoids a slide into self-pity or self-regard. In fact Kupperman complicates the memoir by questioning its usefulness and whether he should have started it at all.

“I don't know what I thought this book would be, or what good it could do,” he says near the end. In a lesser book, this would skirt self-pity. Instead it’s emblematic of a story about self-worth in constant doubt, good intentions falling short, and ambivalence moving down generations. All the Answers doesn’t end with the kind of punchline readers might expect from Kupperman, but if there’s truth in comedy, he hasn’t sacrificed it in telling his family’s own story.