Nick Drnaso's Acting Class weighs in at 268 pages. That's nearly double the number of 2016's Beverly, a book whose back cover blurb said Drnaso had "advanced beyond the comics which have preceded him." It's about 25% more than 2018's Sabrina, which was called "a masterpiece... possessing all the political power of polemic and yet simultaneously all the delicacy of truly great art." Where a comics creator might go after being winched up onto that pedestal is a question to ponder, but the central choice might be to decide whether your existing artistic trajectory has reached full flower and it is time to move onto the risky high-wire of something new, or instead maintain the course that got you to this peak and just go do that voodoo that you do. Acting Class is the latter, new characters animated by something very like the established spirit, in a story inflated to a larger diameter from the inside.

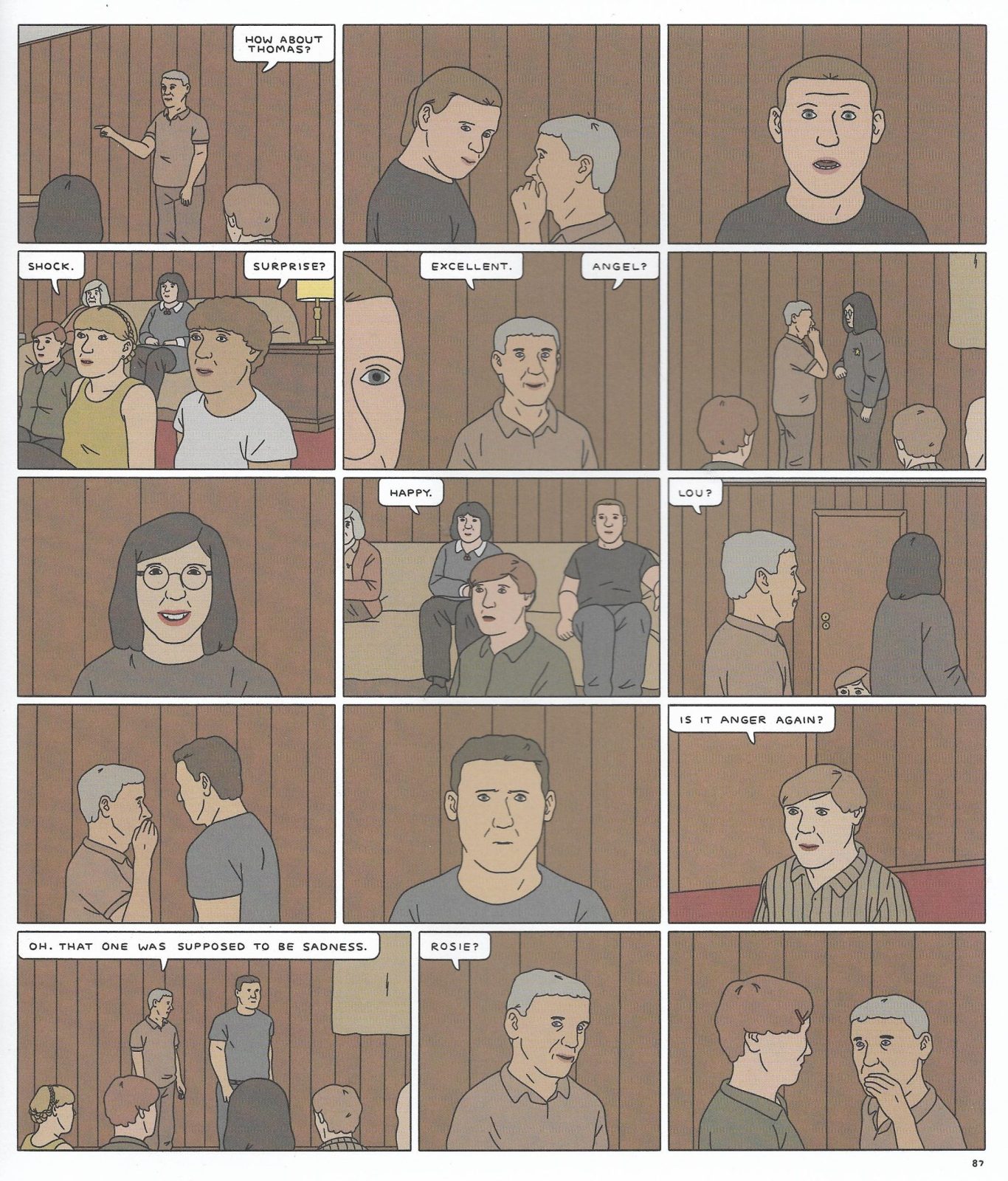

The length is down to the plot, following a dozen working class individuals as their storylines come together, separate, and come together again, plus some extended diversions into their imaginations. This cast includes Rosie and Dennis, an unhappily married couple; Rayanne, whose young son might be showing signs of mental disorder; Lou, a gym rat nursing modern masculine neuroses; Neil, who seethes with suppressed anxieties and wants to be someone else entirely; and Angel, drawn as a dead ringer for the Amy Farrah Fowler character on The Big Bang Theory and conversing like her too. These individuals and a few others enroll as students on a course of acting classes run by a tutor who claims to be called John Smith, although it becomes increasingly likely that he isn't really.

"I assume you've all come here because you feel like social misfits, right?" asks John Smith, embarking on the kind of talking cure that a drama teacher might employ. Or an Amway recruiter, or a cult leader drawing his recruits' attention to their urban ennui. "You're here because something is wrong in your life, right?" At least part of Sabrina's reception was down to its arrival in a fraught Trump moment, and in Acting Class Drnaso circles around a parallel worry: that after a reprogramming from John Smith's perceptual feedback loops, his illuminated students might graduate to living a better life or to storming a government building. But Smith's talk of helping his students to adjust their viewpoints and reconfigure themselves looks a pretty obvious ruse in a modern moment of deregulated capitalism and deregulated reality; if the teacher is really the front man for some shadowy cabal, as Drnaso briefly suggests, then he's doing without the appropriation of cultural signposts and communication channels that characterizes the real ones. That is, if the story's era actually is modern - technology is nearly absent here. No one has a cell phone or sat nav in their car.

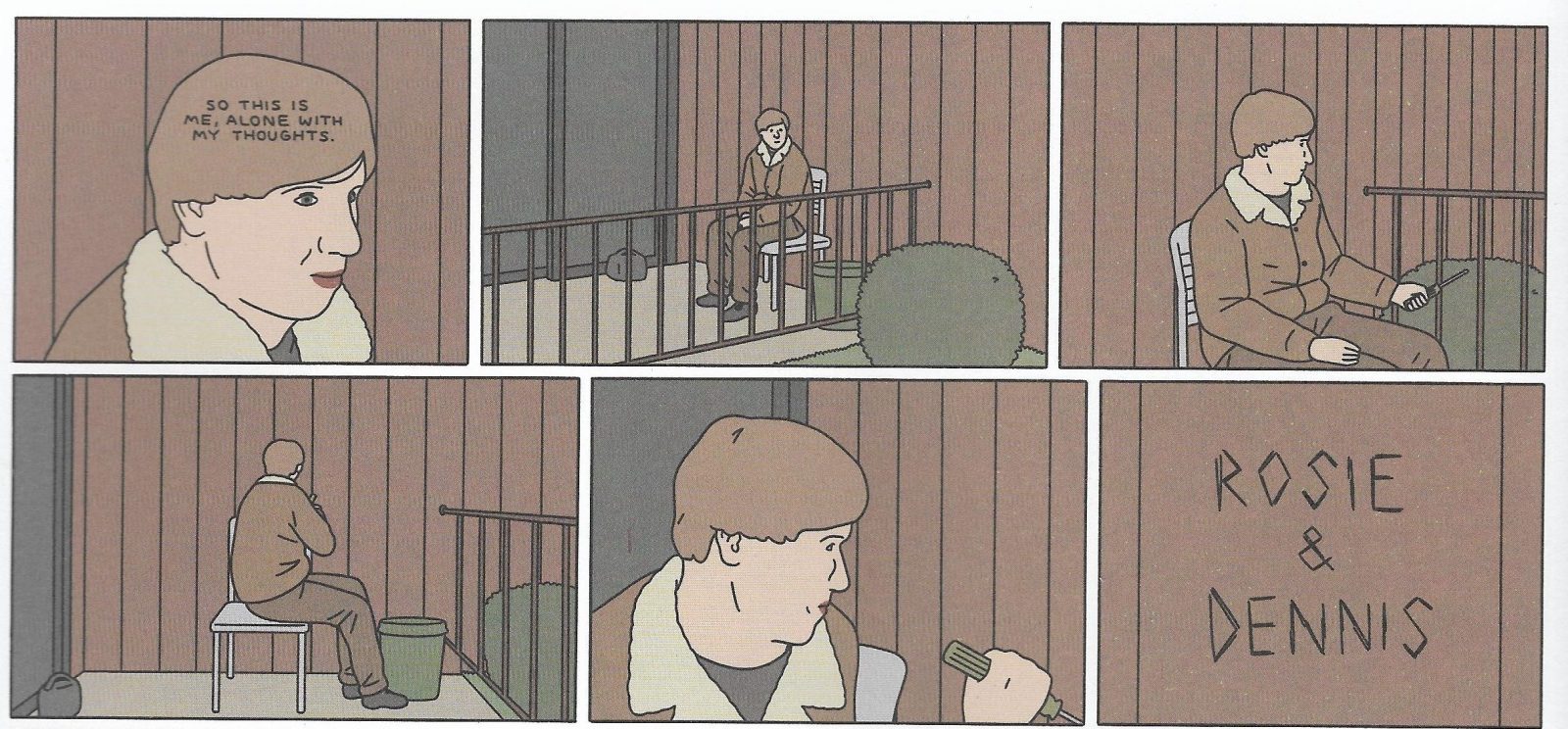

Part of the book depicts a group improv scenario set in an imaginary city center location, and a lengthy later section finds the students making up individual fantasies while all actually lying down silently with their eyes closed, visualizing any locale they care to create. In both cases Drnaso cuts in and out of reality between panels with no visual coding, and renders the unreal in identical fashion to the quotidian figure work and panel rhythms used for Acting Class's reality. Whether or not this means the characters just have very prosaic imaginations, it forces a reckoning with Drnaso's art style, an endothermic minimalism that struggles to suggest any hidden structures of existence and might not care to go looking. In a comic without thought bubbles, when Drnaso needs to show a character being contemplative he writes out the actual words "So this is me, alone with my thoughts" and plonks those letters down directly on the character's head, there being no other route to the life of the mind from the stiff materialist territory the artist has staked out.

In one way, though, Drnaso has changed his art noticeably. For Sabrina he opted not to draw fully-formed eyes most of the time, leaving them as small black periods without eye sockets for anything other than close-ups. But for Acting Class almost every character in the majority of panels is drawn with a roughly-hewn solid oval of eyelids and a colored iris with a black pupil, and as a result the art's affect goes mildly bananas. On the micro scale the storytelling gets dented when eyelines between conversing characters drift panel to panel, shifting with the flexible rendering of the eyes themselves (the fixtures and fittings behind them can slip and slide too, but that's another matter). On the macro scale, the effect is a blanket of modernity, a post-authenticity so-ironic-it's-legitimate look that gives everyone the dazed dislocation of an internet meme.

When the story aims for poignancy, on the whole the eyes don't have it. When it touches on historic sexual assault and child abuse, the affect puts distance between reader and character just at the point where you need to get your bearings. Neil, flagged as mentally fragile but sympathetic, is knocking on doors collecting for charity when a lady abruptly outs him as a child molester who abused her daughter; he wanders off in a daze, seeking absolution from an imagined better version of himself reflected in a window. This drastically severe couple of pages layers ambiguities on top of each other: an abuser's repressed memories or lies; the (im)possibility of forgiveness; the chance of mistaken identity - all in a comic by someone who has spoken of his own abuse. But these ambiguities are squeezed down by the affect of the art into something more like basic pathos.

Pathos is valid currency. Pathos is good, pathos works. It's always been crucial to those indie comics embracing a performative respectability that lets comics be judged on literary and textual values rather than artistic or graphic ones. If there were senses in which Sabrina's story of personal tragedy really had "the delicacy of truly great art" then they stemmed not from the drawings but from the words and their narrative resonance in a decade of disasters - a verdict to be recalled quickly, case closed, before the spirit of R.C. Harvey arrives to question whether the art was involved in this achievement, whether the words and the pictures were mutually dependent at all or going their separate ways after a divorce. Although wanting comics art to be elegant and slick and to hold your hand is a road to nowhere, there's still a difference between drawings made ungainly to imbue them with power and drawings that are just ungainly. That difference is ultimately in the eye of the beholder, like most are. But if an artist reopens a seam of gold that led a previous work to "advance beyond the comics that preceded it," then it's fair to ask whether the new comic built on that hot frontier is making you think, or just making you read.