There’s something going on in A Projection by Seekan Hui, something vaguely sinister and vaguely unsettling, but only vaguely defined. That’s an important feeling to put a finger on, because that liminal realm between the sinister and the unsettled is precisely where the book dwells. There’s a great deal being left out, both from the reader and the protagonist.

The effect is of walking in on the second reel of a movie. That’s intentional, as the book begins with the arrival of Cecilia (called Lily by a callous mother), a new governess, or rather, “Family Photographer.” Her responsibilities are to provide a “Daily document of children, provide care when needed.” Although in practice she’s a governess, the part of her job that the children’s mother is most concerned with is taking photographs, of which a daily quota must be maintained.

A Projection is about memory and loss. The photographs which cover the walls of the house are of the children, and it’s Cecilia’s job to take even more. The problem is that Cecilia is a bit of a perfectionist, and she can’t seem to get it right. She struggles with herself, even down to self-harm. It’s an awkward dynamic because the reader knows that Cecilia’s reluctance to ever commit is at odds with the mother’s desire for a constant photographic record of her children growing up. So of course, there’s a secret. There’s a Victorian bent here, with a haunted house and family secrets waiting to be uncovered by the unknowing outsider. Not a particularly macabre secret – just a death in the family. Someone taken from them before they could get any good photos.

A Projection is a ghost story but not a horror story. The mother isn’t doing a very good job with the children she has left because she’s been shattered by loss, and while her husband seems to be doing better, he’s also a nonentity. Problems arise when the dead begin appearing in developed photos. Cecilia didn’t do that on purpose, obviously, but that doesn’t stop her from getting the blame.

A Projection is a ghost story but not a horror story. The mother isn’t doing a very good job with the children she has left because she’s been shattered by loss, and while her husband seems to be doing better, he’s also a nonentity. Problems arise when the dead begin appearing in developed photos. Cecilia didn’t do that on purpose, obviously, but that doesn’t stop her from getting the blame.

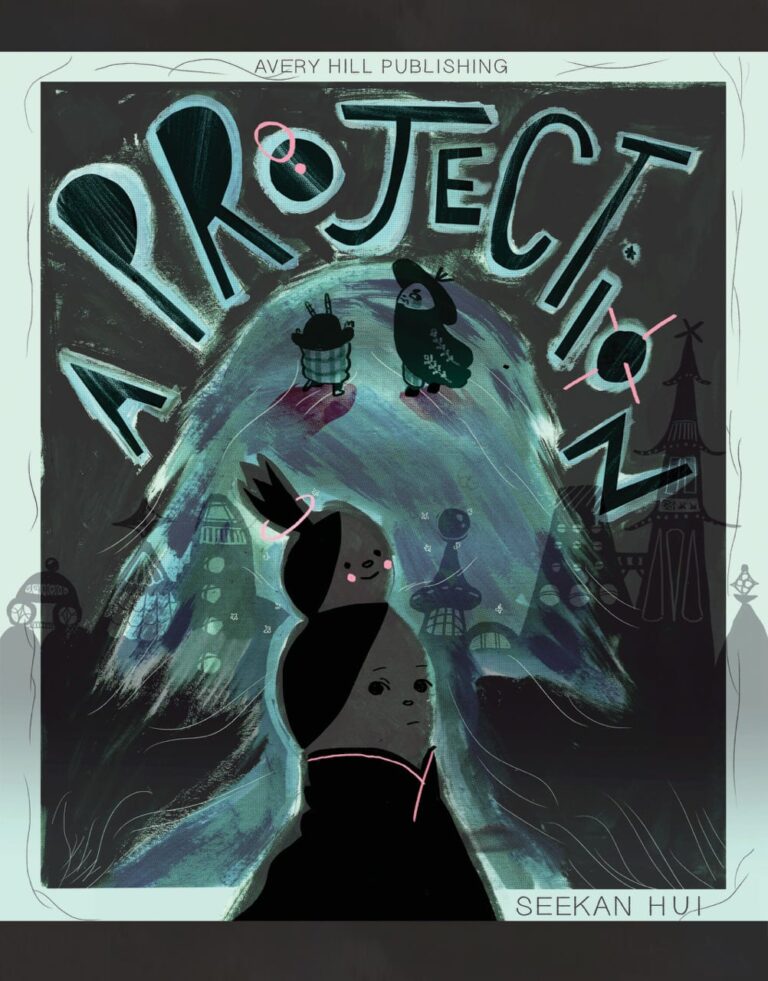

Hui’s art rests in that niche between sinister and unsettled. Her art is dominated by her expressionistic character designs. For example: Cecilia has two heads, one on top of the other. The two heads talk to each other. The other characters notice this – one of the kids asks “Y do u have 2 heads?” on a piece of toilet paper passed under the door. But it doesn’t seem any more unusual than the fact that the kids are ladybugs. Hui’s style doesn’t always work that well in some instances. It’s hard at times to follow precisely who is who when, from a distance, the children can appear as angry squiggles.

There’s a fussiness to Hui’s work that occasionally works against the story. Sometimes designs which seem interesting in isolation can read as oppressive or confusing on the page. It took a few reads to get the plot because of this. Cartoonists who largely eschew panel border in favor of more wide-open compositions that lean heavily in the direction of montage, as Hui does here, need to make sure their storytelling is clear enough to overcome the noise of crowded and colorful pages.

There’s a fussiness to Hui’s work that occasionally works against the story. Sometimes designs which seem interesting in isolation can read as oppressive or confusing on the page. It took a few reads to get the plot because of this. Cartoonists who largely eschew panel border in favor of more wide-open compositions that lean heavily in the direction of montage, as Hui does here, need to make sure their storytelling is clear enough to overcome the noise of crowded and colorful pages.

Before all is said and done the remaining children will take flight (that’s not a metaphor, as they really know how to fly) and the mother will finally take the opportunity to come to peace with her loss. One of comics’ great strengths is the medium’s ability to illustrate altered or distorted states of being. Hui’s character designs stretch the limits of legibility, but her skill with color and composition means that the book looks beautiful even when you find yourself spending a minute staring at a page that stubbornly refuses to cohere into narrative.