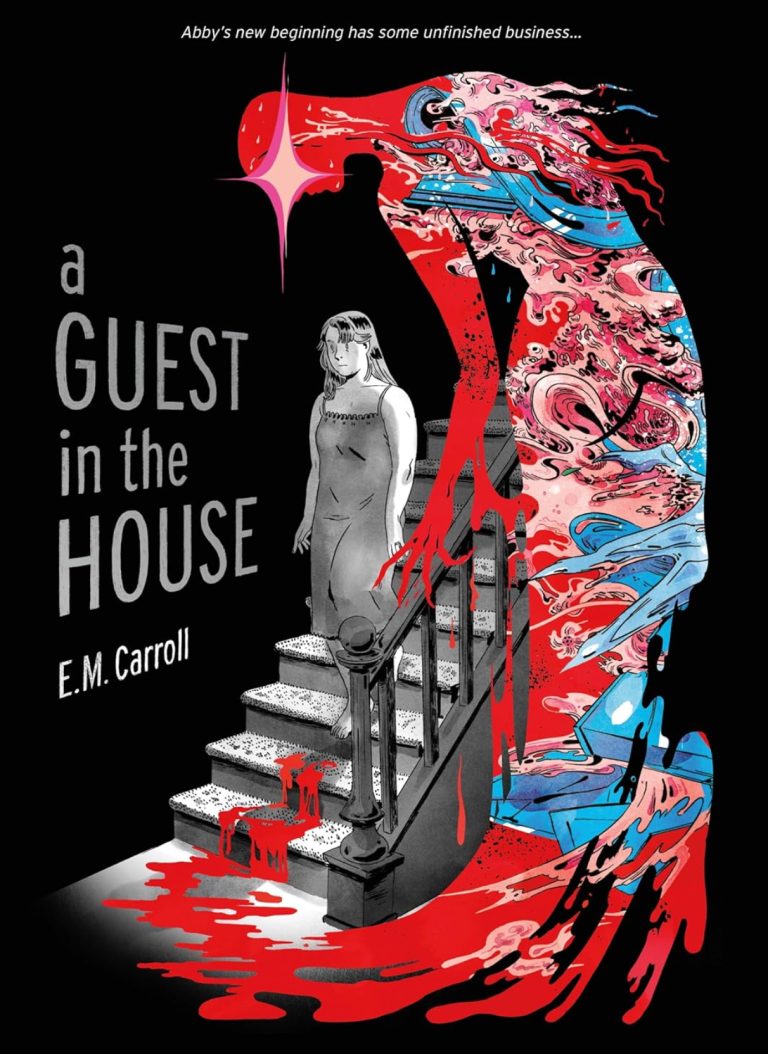

Emily Carroll’s A Guest in the House is a resounding success of horror in the medium of comics. It follows Abby, a woman who becomes haunted by the ghost of her new husband’s late wife as she tries to navigate her new roles as a stepmother and wife. At its most basic description it sounds like a dime a dozen horror stories, spanning from gothic literature to the most prototypical ghost movie, you await the bluebeard’s bride twist and the reveal that Abby has been living with the true monster all along. Carroll goes beyond the many preconceived notions of the genre to explore identity, isolation, what it means to belong, and that perhaps the monster has lived beside Abby long before her marriage.

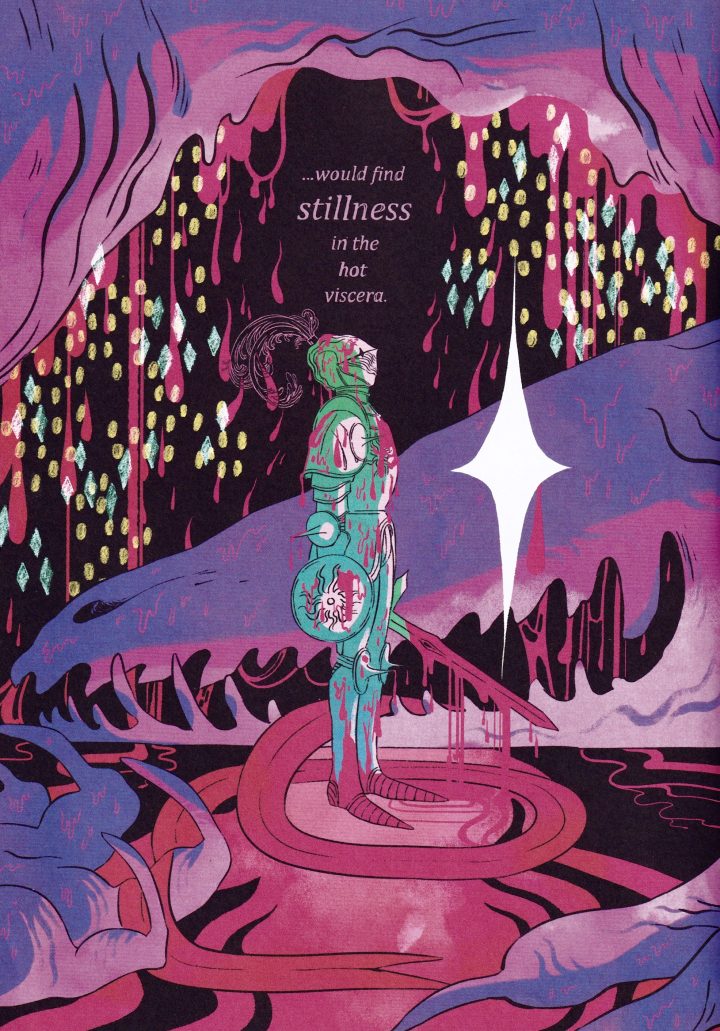

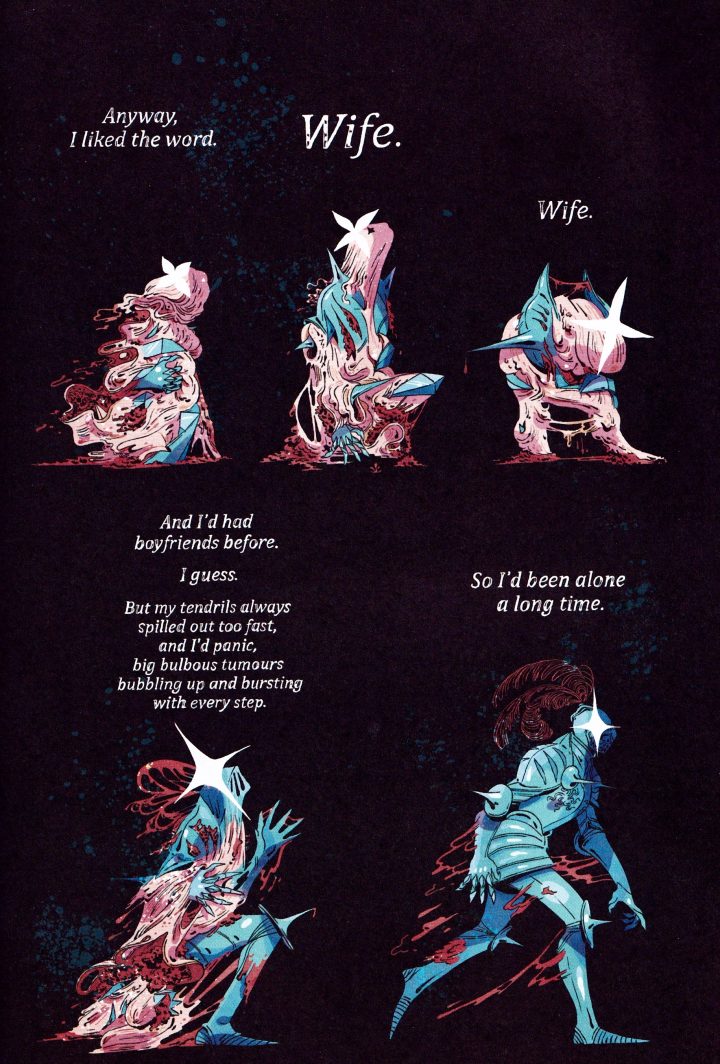

The comic opens with Abby’s description of her childhood dreams, where she is a knight who kills a dragon; displayed in a riot of pinks, purples, and greens, the dragon’s blood rains down on her. As we follow Abby into waking life the comic moves to be almost entirely in black and white. Abby’s reality is neater, with smaller more contained scenes, straighter lines, and devoid of color.

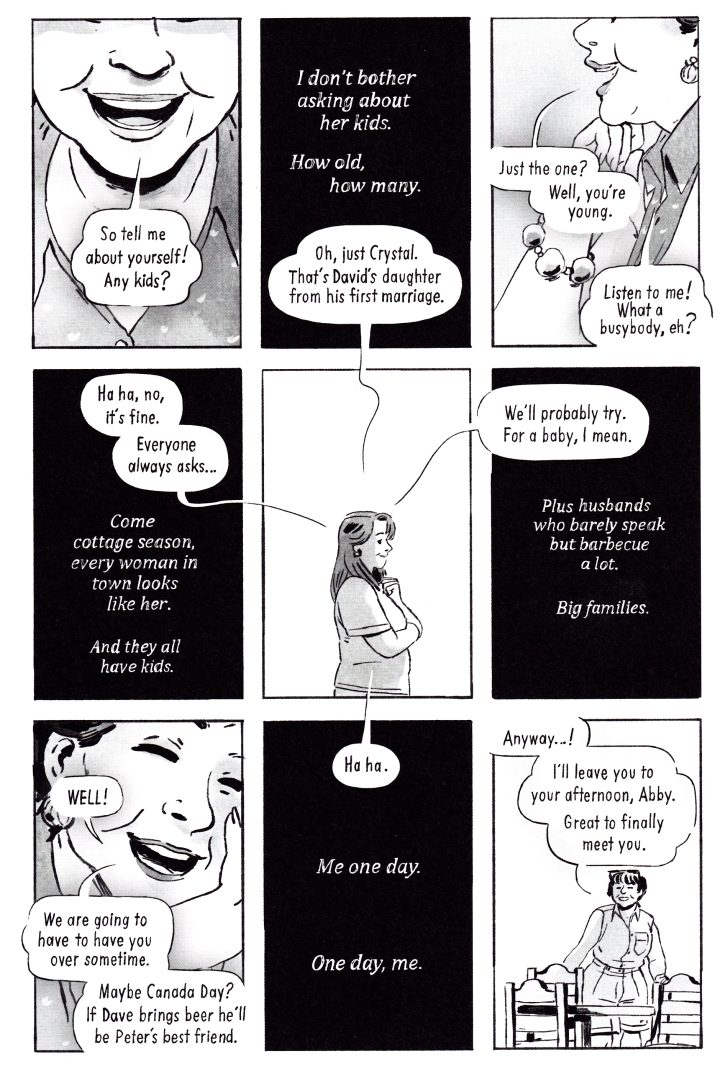

We are introduced to a seemingly ordinary ghost story beginning with an ordinary family. Abby settles into her new home by the lake, musing on her relationship with her husband David and her stepdaughter Crystal, with whom she has not yet managed to form a real relationship. Already we begin to see Carroll’s mastery in how she frames this tired setup. The comic is narrated entirely by Abby, and her internal world is at once poetic and honest. While horror media often focuses on falling short of the ideal nuclear family, this can ring hollow as we watch people who look like models, with only vague personalities, and only plot convenient financial issues, play house. Here we immediately feel Abby’s own fears and inadequacies, learn intimate flaws that are both grounded and extend beyond the immediate situation at hand. She is withdrawn, has body image issues, is insecure in her ability to meet the expectations of being a wife.

Key to bringing home the reality of these characters is not just the prose, but Carroll’s depiction of people who look realistic. Her ability to draw people simplistically, with an economy of lines, yet still imply fully realized characters is another clear strength. Characters have body fat, wrinkles, and unflattering haircuts. These details bring the reader into a story that feels more grounded and family issues that feel less contrived, as well as breathing new life into the ghost story genre. Abby is drawn expressively and subtly, giving us a window into what she experiences beyond the narration.

Abby’s interiority is essential for the story that Carroll presents to us, where horror emerges not from an outside source, but from within. There are elements of horror in these mundane, inescapable roles that Abby finds herself in. Her black and white days are peppered with subtle criticisms at her job, about her housekeeping, and her attentiveness to Crystal. Though the expectations placed on her are oppressive, Abby talks more about her fear of herself, of what she would be without these roles to define her. She talks about being unformed, unconfined to one shape, messy and amorphous in a way that is at least unpleasant if not dangerous. She views becoming a wife as a suit of amour, plucked from her childhood dreams, the role of the amour is not to protect her but to form her into one unchanging shape. Through being a wife she is confined but also given form, a way to move through the world. She is given a script, and others are given an easy way to interpret her.

It is through this conceit that A Guest in the House delves into themes of queer embodiment and repression, exploring the fear of unrealized identity. Abby’s uncertainty in her own identity, and her resulting lack of connection with the world, is a heavy background buzz throughout the grayscale narrative. There is an element of this that is universally relatable, the fear that you are going through the motions, that you don’t understand where your own feelings arise from, that it is vulnerable and dangerous to reveal your true self. But beyond that are hints of Abby’s unrealized desires, and that the container she uses to constrain herself is an aggressively heterosexual one. While during the day she stumbles through attempts to be a perfect wife and mother, at night she envisions herself as a knight trying to save a princess from a tower.

In Abby’s dreams, and nightmares, and hauntings, splashed in vibrant color, she imagines herself as someone powerful, an active narrative force. Unlike the role she takes on during the day, one of listening to her husband, carefully catering to his needs, at night she takes on a prototypical fairytale role, one that involves saving and protecting another woman. It calls to mind some of the most influential lesbian shoujo, The Rose of Versaille and Revolutionary Girl Utena, which play on this role of protector and knight in their exploration of queer romance. Though the woman she is haunted by is the ghost of her husband’s dead wife, she envisions her as a princess, idealized in a way that none of the other characters in the book are. Certainly it connects to the ways in which Abby feels inadequate as a wife, a mother, and a woman. But also it hints at her own desire for this unachievable woman, as someone outside of herself that she could be loved by. This fantasy is dressed up in a childish costume, making it both less real and safer, layered over the image of Sheila’s ghost. Her haunting, when not clothed in fairytale, takes the form of a seduction. She has secret late night talks with the ghost where she is able to confide in her, the ghost comforts her when she cries, and when Abby gives in to the ghost’s desires they share a single passionate kiss.

There is also a certain prolonged childhood to Abby’s experience. Whenever color enters the comic it is associated with fantasies or dreams, and occasionally in the childish drawings Crystal makes. Abby clings to ideas of knights, dragons, princesses, which we discover were inspired by a picture book when she finds a copy of it in Crystal’s room, depicted in full color. We are left to wonder why Abby’s internal life is still so influenced by these childish ideas. Perhaps her imagination of the future is stunted, stuck in an eternal childhood after the death of her older sister when she was young. Perhaps it is this amorphous sense of identity; that with no satisfaction in her adult life she is left rehashing childhood. Either way it furthers Abby’s disconnect from those around her, widening the distance between her internal life and the conversations she has with coworkers and her husband.

This gap between Abby’s internal world and what others are experiencing is where the horror of A Guest in the House truly lives. The narrative walks a path that has been tread before in this regard as well, telling a story where the supernatural might all be a result of Abby’s mental illness. However, I at least am uninterested in prying apart the reality of the supernatural from Abby’s own reality, one that we are drawn into, one that we can’t help but believe. In the final moments of the book we are faced with the fact that the ghost that Abby has been seeing can’t possibly be Sheila; she is alive and well, and has come to try to reclaim Crystal. This moment of realization clarifies many things; her husband had not killed Sheila, he had indeed been lying to her, Crystal may have actually seen her mother outside their house at night. It leaves one key question. Abby turns to the ghost, the one who has haunted her, the one who convinced her of her husband’s guilt, who she sees as both princess and drowned corpse and asks “Who are you?”

This is the question that lies at the core of the story. Who is Abby? Is she the knight or the dragon? Protector or perpetrator? Delusional or haunted? Abby never gets to find out, and with only her point of view we are left to speculate. It would be easy to say there was never any ghost at all. But maybe there was a ghost, one who used Abby’s own uncertainty, one who used the story around it to find its shape – both Abby and the ghost only able to hold their form through the identities they take on.