Centrala is an interesting new publishing concern that's part and parcel of the growing expansion of Baltic and Eastern European comics into English-speaking markets. Indeed, even though most of its artists are Polish, Centrala itself has an office in London and publishes books in both Polish and English. It's also a key player in Ligatura, the annual art-comics festival in Poland. This edition of High-Low will survey Centrala's early and recent output, which ranges from all-ages material to autobio to stuff that's far stranger. While there's a provincial quality to many of these books, they also frequently hit notes that will be familiar to fans of American and other European art comics.

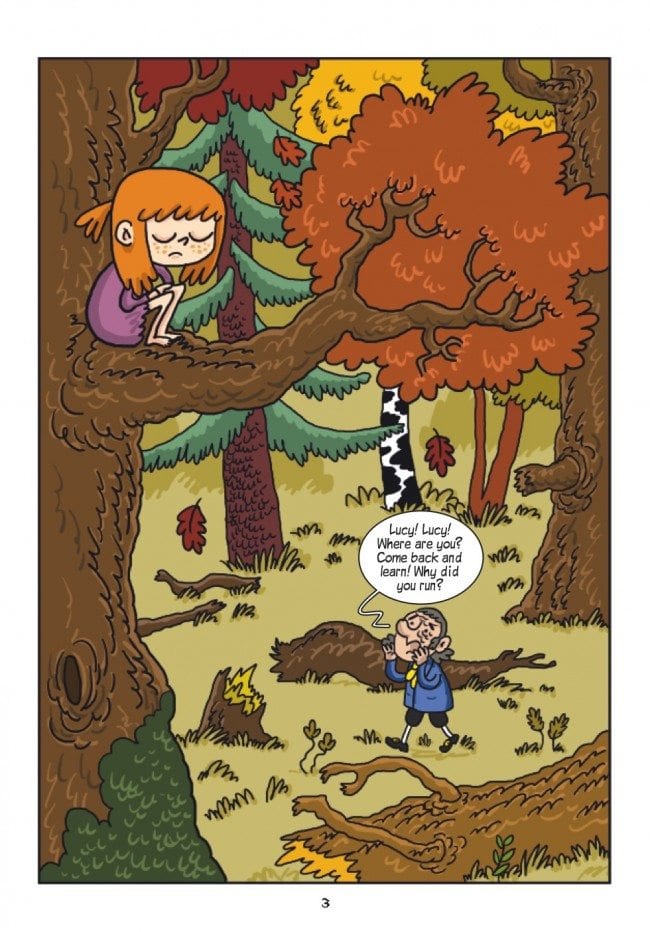

Forest Beekeeper and the Treasure of Pushcha, by Tomasz Samojlik. This is an all-ages book that wouldn't be out of place in Top Shelf's or First Second's library of authors. Set in the late 18th century, it's a story that firmly mashes up myth with history and is drawn in a cute, cartoony manner. It's about the Poles' frequent enemies in Russia dividing up conquered lands; in particular, this book is about a particular pushcha, or forest area. Samojlik goes into great detail regarding the culture surrounding this forest preserve, the beekeepers who lived out in the open and made shoes of bark, and the fables surrounding the enigmatic White Beekeeper and the treasure he guarded. The drawings here are truly over the top; the evil characters look really evil and the good eyes are drawn as cute and cuddly. What sets this book apart is the considerable amount of research into local color and other facts that bind it to Poland's past and present.

It's Not About That, by Piotr Nowacki and Bartosz Sztybor. Nowacki is the artist and Sztybor is the writer in this surprisingly dark story about a servant robot looking forward to its retirement. Nowacki draws in an exaggerated, almost bigfoot style, which is important because this is a silent story. As such, he gives himself license to draw his simple figures with stylized and distorted facial expressions; it's an effective and even amusing shortcut for getting across mood, especially when paired with the bright pastel colors of the book. The poor robot is consistently abused, ignored and/or unappreciated by his "family," and when he learns that his real future fate is not retirement on some tropical island but an ignominious end in a dumpster, that's when the story gets dark and enormously clever. Here, the silent beats and off-panel machinations lead to a remarkable punchline, as the robot manages to retain his job but with no illusions about his future or his role with the family.

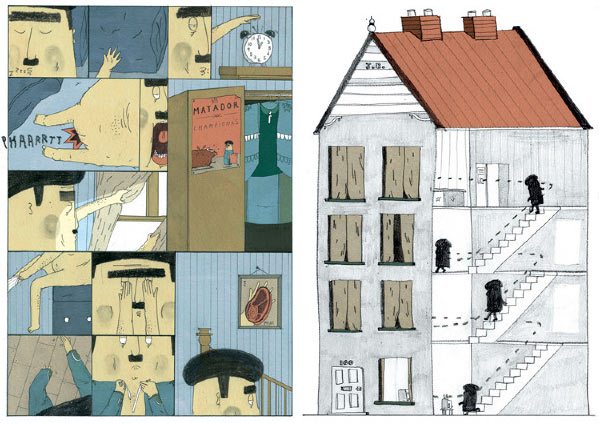

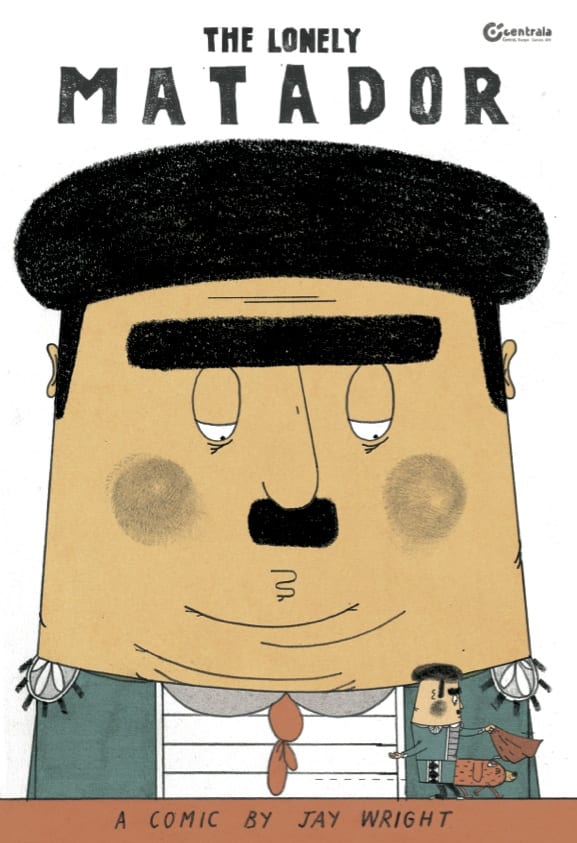

The Lonely Matador, by Jay Wright. This book won the festival prize at Ligatura in 2011 and is a perfect representation of the Anglo-Polish nature of Centrala, as Wright is from Great Britain. The book is a slightly fictionalized biography of the famous bullfighter Juan Belmonte, a brilliant and innovative tactician who overcame deformed legs to become a legend. The story picks up in the early 1960s, before Belmonte's eventual suicide, and it spends a whimsical week with Belmonte and his equally sausage-shaped dog. This is an odd comic/children's book hybrid, as there are all sorts of the gimmicks present in children's books, yet there's a palpable sadness felt throughout the book. The gimmicks work as clever narrative shortcuts. For example, when Belmonte opens up a packet of photos, the reader gets to open up that packet and actually look at each photo (as a series of cards), which serve to offer up a number of narrative clues regarding his life.

Lynch really knows how to work a page's negative space, as in the way he frames stairs as a sort of obstacle and narrative device. He includes inserts like a meat-market circular, a piece of vellum covering up his dreams, and a poster of a long-ago fight. Every page is a series of silent visual problem-solving techniques, which manages to capture the cheeky fighting spirit of Belmonte as he rages against boredom and retirement itself. There are scatological jokes as well, which befits both the book's nature as one for children as well as one that reflects the visceral and sometimes vulgar nature of his life. This is a book where one can see Centrala's painstaking attention to detail and production values.

Blacky: Four of Us, by Mateusz Skutnik. This was my favorite of the Centrala albums. It reminds me a bit of Lewis Trondheim-style autobio (in the vein of Petits Riens), only Skutnik draws himself and his family as gremlin-like elves. The long ears, shadowy features, and intense eyes are simply fun to look at on the page. Skutnik's curmudgeonly wit mixed with a surprisingly affecting account of his interactions with his young daughters make each page a roller coaster of emotional states, from contentment to exasperation (his struggle with a vacuum cleaner) to philosophical resignation (at his father's grave). Sometimes it's simply witty (like his sarcastic musings about his mother and how little she knows him). He drops line after line and image after image on the reader as the book meanders through events like a regular working day, a haircut and a day at the beach. The best page of all is a splash with a demented figure that reads, "And the Old Grandfather Time sits on his branch and goes, 'He he he he he.' Just like any other psychopath." In the end, there's a kind of triumph, a powerful realization that this is precisely the life he wants to lead. This is clearly a work by an artist firmly in the mature part of his career, one with a lot to say and one who knows just how to say it in his own style.

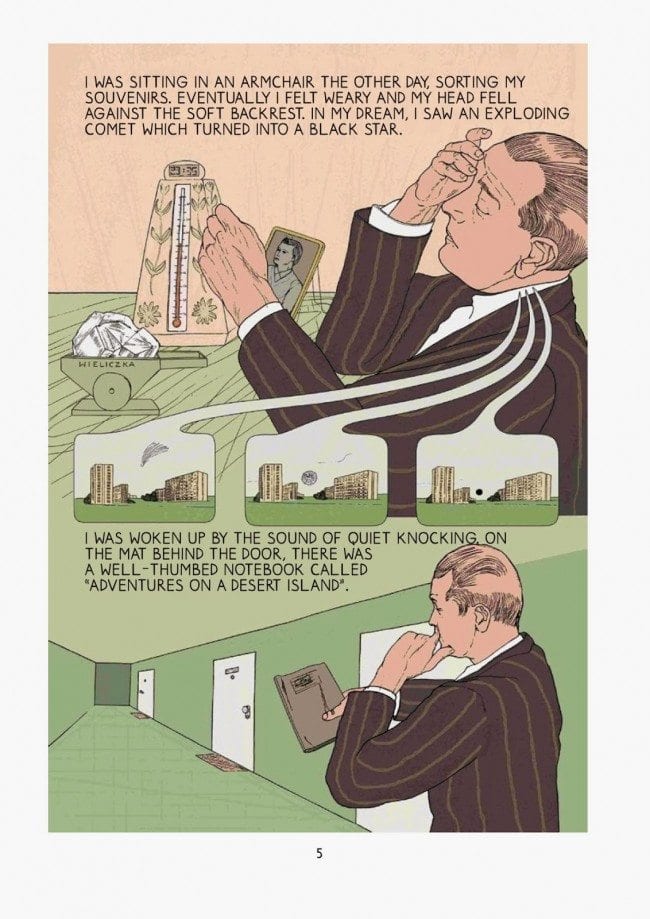

Adventures on a Desert Island, by Maciej Sienczyk. With deliberately stiff and posed figurework and a use of color that is at once garish and unintuitive, Sienczyk's book is by far the most daring and weirdest of Centrala's offerings. It's about a man who is mysteriously given a notebook titled Adventures on a Desert Island, which is about a man's journey on a boat, the boat being sunk by a huge wave, and subsequently washing up on an island and his eventual rescue. That basic plot, though it does have some strange twists and turns, is incidental to the real purpose of the book: characters telling strange stories to each other. These range from the relatively mundane, like one featuring a highly sensitive and emotional man, a sweaty but virile man, and an attempt to find out where money was hidden by a dying grandmother, to more outré tales featuring experiments with telekinesis, time travel, and dead women haunting their relatives for failing to have them buried in a bra. There's a weird slipperiness to this book's stories that makes it feel like a compendium of folk tales and stories overheard at bars, done in the style of an artist like Olivier Schrauwen. The fact that passing along these stories supersedes nearly every other human need in the book (including basic survival!) speaks to our need to spin and control our own narratives; in situations like this, they're almost a form of currency.

Silence 2011. This is an anthology of the entries for Ligatura's "international silent comics competition," published in alphabetical order. Several cartoonists who specialize in silent comics (Tom Gauld, Erik Kriek, Tim Molloy, Andrzej Klimowski) made up the jury that determined first, second, and third place. First place went to Polish cartoonist Marta Dlugolecka's "Bath", which is constructed using sculptures and photos to tell a narrative about a girl in an orphanage who turns into a mermaid. Dutch cartoonist Bart Nijstad's photorealist comic about a man being hypnotized and going through some truly remarkable and strange images won second place, while Brit cartoonist David Peter Kerr's graphically striking exploration of time and space won third.

The anthology is less edited than it is simply laid out, and so the effect when reading it is jarring at times. The quality of the pieces is understandably uneven, both in terms of drawing and storytelling. There are some striking illustrations that don't work as comics and some scribble comics that are difficult to parse. Some of the works were clearly designed to be published at a larger scale than the book's roughly 4" x 6" format, and are hard to read as a result. A couple of artists whose work stood out were the UK's Kripa Joshi (her Miss Mota strips are smoothly well-designed, funny and politically pointed) and Argentina's Jorge Quien, whose comic about a walking mountain reminded me a bit of Mat Brinkman.

Silence 2012. This volume more than doubled in size from the 2011 edition (248 to 523 pages), which points to the increasing interest and influence of Ligatura. Limowski dropped out of the jury but the other three judges remained the same, and the results reflected their interest in a graphically diverse and challenging style with a bit of flashiness to it. Once again, there was a trend toward formal flashiness by the judges. I thought the collaboration between Dzian Baban, Vojtech Masek, and Jan Siller ("The Oysters Of Time") was a worthy winner, with its naturalistic pencil style reminding me a bit of Thomas Ott's horror comics by way of a surreal mirror. John Martz's piece, "Heaven All Day", was later reprinted at a larger size, which made its mad scientist narrative breathe a bit better; it's another worthwhile piece. I did think that the third place piece, Jonathan Savebois's "Cal", was more stylistic pyrotechnics than substance, especially with strong entries from artists like Dunja Jankovic, Emilie Ostergren, and Ludmilla Bartsch. I thought the latter did an especially good job of capturing the spirit of the anthology's theme in its use of all-black speech balloons oppressing a sensitive young girl. Overall, this massive book is a fine example and snapshot of European alt-comics in 2012.