GROTH: Do you see any way out of this? I mean, obviously you think that totalitarianism in China is wicked, but you also tend to think that the kind of “democracy” you have in England is, in its own way, wicked, too.

STEADMAN: Well, it’s wicked only because it’s insidious. I think it’s wicked because it gives a false sense of security: things are great, and a smart front window is all we need; the shit that goes on in the background is unimportant so long as the Jaguar in the front window is polished everyday by the salesman, but it’s for sale and someone’s going to come by and buy it — on credit, of course — but they’ll buy it. To keep up appearance; appearances seem more important to people than reality. I think we’re heading for something very interesting in the final 10 years of this millennium.

GROTH: I want to ask about the European elections: why do you think a rejection of Thatcher’s economic isolationism would push people to vote for the Greens?

STEADMAN: Well, people have realized that their financial growth, their financial patterns, are unsustainable — particularly in a world that’s choking to death. I think, in a peculiar kind of way, that we’re up against a wall. We’re being quite realistic. This might tend to contradict what I just said about Spitting Image and watching programs that make us forget; it’s slow. It’s still small, about two million votes from us [Britain], but it’s quite a substantial number of people voting Green rather than Labor and Tory, which they probably voted for before. And they took the votes from the middle class, the Liberals and the Social Democrats. It’s a significant move. It’s not decisive yet, but it is at least a move in a direction which we’ve never been in before. So we are aware of something. I mean, two million people are, at least. Probably a lot more, who, when it came to voting — once they got inside the voting booth, they suffer from terminal anxiety, which is what they call that moment when you put a cross on a piece of paper — and they suddenly revert back to the old habits of wherever they used to vote. A lot more people probably would have voted if they hadn’t suffered that particular moment. They just thought, “What the hell, I want the change.” They don’t altogether want it yet. People tend to have strange feelings of nostalgia for things that have been, and things as they were, and part of them hopes it will continue like that, whilst the other part of them demands change but isn’t quite strong enough within himself or herself to allow it. When people get into a revolutionary state of mind, I think it’s at that point that the human mind overcomes physical fear because it’s shit or bust.

Something has to happen, even at the expense of imminent physical danger. It seems that one can’t go on the way one’s going on, so therefore you enter that revolutionary state of mind when you really can’t stomach it any more. I think that’s what’s happening in China. They believed, perhaps, that to be the new order. Our tourists looked so happy and self-assured— a walking advert for Western ways. There’d been such an invasion of Western ways that, unfortunately, they always get blinded by that. I think half the students are talking about a democracy which is a Western democracy and, in a funny kind of way, it’s not really a democracy. Maybe they believe it to be. Maybe it is in relation to their kind of life, but it’s not a wholly fair democracy. In some ways, the fact that we got two million votes — I say “we” because I voted myself for the Greens this time — but I just thought that having got two million votes and no seats doesn’t say much for the democracy or how we run things over here.

GROTH: Yes. Now, can you explain why the Green Party got so many votes and yet didn’t attain any seats?

STEADMAN: We don’t exercise proportional representation; it’s not done on that basis at all. It’s just first past the post. You may get a lot of constituencies which have candidates that get a small vote but beat the others because there isn’t such a turnout, so they get in. It’s not based on the number of votes at all, but only on the number of seats that are gained. So Maggie’s actual majority is practically nil, and yet she exercises a huge mandate over everything we think and do, and she’s done it for 10 years and she doesn’t have to go out, either. What kind of democracy is that? We have no say in the matter. She could stay till the end of the century, probably as long as she can crawl. Since this new European thing has come up, I think it’s begun to show that she’s a kind of a nanny figure that’s rather pre-venting us from seeing what’s on the other side. She doesn’t want to lose control, and she will as soon as we go into Europe proper. I don’t think she’ll have the same kind of influence abroad as she has in her own place. Maybe she will. [Laughter] We didn’t like her throwing her weight around, you know. She has a style: before anyone else says anything, she’s already made her presence felt.

Anyway, this is a terrible subject to speak about on a Monday morning. What else do we need to talk about?

GROTH: For our cover we are using your drawing of the masses worshipping the U.S. Constitution in the shape of a dollar sign. I was wondering if you’d just talk about that for a minute. What line of thought inspired that image?

STEADMAN: I think it was Newsweek that asked me to do something about your Constitution and your way of life, and I thought what your way of life projects more than anything else is a love of your Constitution, but first a love of money in order to live by your Constitution comfortably, because a lot of people can’t live by it comfortably. In fact, a lot of people during the civil rights movement actually found at great cost that it didn’t really work in their favor; they didn’t actually have the rights that they thought they had. But the thing that was in the Constitution’s favor was the fact that it was written down — so with the right kind of civil rights movement, the right kind of pressure, eventually it could come to mean what it says: that everyone has the right to a fair hearing and everyone has the right of equality. The blacks had to prove it, and so did a lot of other people. You have a poverty bracket, haven’t you — a poverty-stricken underclass beyond the Constitution’s effectiveness?

GROTH: Oh, yes.

STEADMAN: It’s not what America projects. I mean, most people wouldn’t think of poverty in America. I thought, “They’re very proud of their Constitution, their written Constitution, provided it’s endorsed with the backing of money and power, wealth, influence — pure capitalism. It works while everybody’s doing OK. Really, that’s what they’re buying into: that’s what they’re praying to; it’s their altar. But it has to be money. You probably couldn’t exercise that Constitution in a poverty-stricken country. It would probably lead to anarchy, and you’d have to restrain it.” Did that make sense to you, what my drawing says?

GROTH: Yes, but of course it leads into the conundrum that if the freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution couldn’t work in a society that didn’t have a high standard of living, we’re not living by the ideals of the Constitution so much as we’re using it as a means toward greater materialism, and worshipping the Constitution for the wrong reasons.

STEADMAN: Oh, yeah. I suppose that one thing leads to the other. We’ve created a Constitution; now we must make our people prosperous, or at least a certain number of them. This is where to me the contradiction is: some people have a better chance than others to realize that dream. The American Dream is really riddled with inequality. It’s that, I suppose, your civil rights movement has been about all these years. And, in fact, you even claim to be a Christian country, and yet you don’t practice Christianity. I don’t mean in a religious sense; I mean in a fundamental sense: helping one’s neighbor, brothers all, that sort of thing. It really is raw human nature that works best in America. All the devices, all the wiles and cunning of human nature work best in America.

It’s the structure of the way your economy works, the structure of your society, that doesn’t much allow for people to be kind and generous and gentlemanly enough to say, “After you.” That’s the same everywhere, it seems to me.

I despair of it ever coming about, but people must think of the next person; I mean on a general level, everyone feeling like that; everyone’s got enough. What a Utopian thought, but it’s never going to happen. I could actually believe it might happen, say, 30 years ago. I believed it. I imagined there was good and bad and all that. I imagined all those things were going to change: “We’re just emerging from the dark ages,” you know, “and it’s all going to be great; the ‘60s are showing us the way.” And then what happens? You get this kind of reversal almost, this back-pedaling to a time which is more like jungle law again. It feels like it. I mean, people talk about it. Generally, it’s in the air. People even worry about it, yet they continue the way they continue because everyone else does, the scrambling up the ladder. You can tell, the way they insist on their children’s school record being absolutely beyond endurance; they pressure their children be like the parents before they’ve even had a chance to be children. That is a sad reflection on our society as well. Children are no longer allowed to be children.

GROTH: How do you mean that?

STEADMAN: I mean that in a way that they start growing them up from an early age to be vocationally-oriented.

GROTH: I see.

STEADMAN: And they develop their children’s interest towards business; they don’t channel their interests toward just what a world it can be, wonderful possibilities of such a world.

GROTH: Yes, instilling that entrepreneurial mentality into the little tykes.

STEADMAN: Right away. Right away. I always thought you could teach a child anything, anything at all — but we teach children the worst instincts. We develop their worst instincts, the ones that encourage intense internecine competitiveness. Within their own kind, they’re competitive and ruthless. They can be friends with someone, and the next minute they can be shitting on them because it’s business. The parents teach their own children to shit on their neighbor or go under. They plant the idea, and the idea leads to the kind of paranoia that drives those very children as they grow up to become little — what were once yuppies now are just capitalists. I suppose, basically, I’m not much for capitalism because I don’t think it’s very productive. It creates a desperate man, you know; it creates a place where the soul dies and life is devalued. It doesn’t say much for it. It may be good for the economy, but somehow that’s the way we’ve chosen to build the economic structure of the whole world: to be without compassion, soulless. And is that the kind of world we really do want? Maybe it is. Maybe it’s got to be like that. Maybe it’s the law of the jungle of sorts, but it’s an economic jungle.

We’ve done it now, and I don’t know how we can undo it, because we’ve still got a Third World coming close on our heels that wants the same. I have a hunch that the West will have to go [Groth laughs] to make room for it.

GROTH: Right. Well, there is a problem that the underprivileged in the Third World countries want exactly the same thing that —

STEADMAN: Perfectly. They can see it. I mean, the adverts have got that far, and now they know exactly what it’s like, and they want to taste the fun. Why shouldn’t they have a Porsche, all of them; why shouldn’t they pollute the atmosphere? At the moment, I suppose — along with the things we’re now beginning to phase out, like food with no preservatives and non-biodegradable products like plastic — they want all those sort of things that we’re now beginning to try to overcome and use much more recyclable things. We’re sending the Third World all the rubber cheap things and the rotten stuff with products in them that we wouldn’t give houseroom to, including CFC spray canisters. We’re sending them all over to the funny little supermarkets you find in places like Acapulco. They’re probably all finding their ways to Third World countries right now. They’re getting used anyway, because there were millions of them produced — and can you imagine any one of those companies that produced them going, “Oh, well, we’ll call that a loss, and we’ll start again and produce the environment-friendly sprays,” or, “We’ll recycle them, ship them out somewhere else; they’ll use them in Bali, or generally around Indonesia, and all those countries like Ethiopia,” places where they might have a little store; they’ve got to take anything they can get. So none of that stuff that we are trying hard now to stop using, none of it is going to be destroyed. It’ll be used somewhere else. People will make a bit of money on it elsewhere.

That’s another aspect of how this economic system of ours works. It’s all based on that, really. The morals become the matter of money, really. We shape our morals to the amount of money we’re making, and then we find ourselves locked into the structure. I suppose that attempt in the ‘60s of people to drop out was a very serious attempt to — I don’t know; start an effective movement away from the very economic structure we’re all falling into. I don’t know if you agree with any of this or think it’s all bullshit, but I’m just thinking now of how we find ourselves, and then how difficult it is to get out of it because we are now structured human beings, and we’ve got a Third World straight on our heels, waiting for the same thing. I do, in fact, happen to agree with the main gist of what you’re saying, and — particularly as someone who tries to be mindful of aesthetic considerations while working within a grossly materialistic social context — it’s all the more demoralizing because I have to deal with this kind of Darwinian milieu in a very direct way every day, day in and day out.

It must be demoralizing for anyone who simply does want to go on with life without being a hideous monster. I mean, it’s society turning us all into those mindless creatures. It must have that effect, because if you bring up any creature in any kind of strange or aggressive environment, the creature becomes aggressive. It’s just like bringing up a dog: you can be kind and gentle with it and sort of gradually reason with it. You’ll never quite completely kill its canine instincts, but at least you’ll get it reasonable. Whereas you’re encouraging people to grow up with a certain attitude which equips them for a certain kind of society which unfortunately we seem somehow to be stuck with. It’s just like a lesson in logic to me; Why are we in the state we’re in? Why have we got to seem so disillusioned? We’re disillusioned because we really haven’t got any real, generally spiritual aspirations any longer. Again, I don’t mean this at all in the religious sense. I mean it simply in the general sense of what constitutes a civilized human being.

GROTH: I think the worst of it is that the economic pressures always result in some form of debasement.

STEADMAN: It seems to have to be, by the very way we’ve structured it. What a terrible admission. What a shocking indictment of the world we live in. There shouldn’t be any need for satirists and savage commentators and the like. [Laughter]

GROTH: Right, or at least less of a need for them.

STEADMAN: Yeah, less of a need for them. I mean, the state we are in now, I suppose, is almost a model of satire, isn’t it?

GROTH: That’s right. In reading your introduction to Treasure Island, it occurred to me that you saw the Treasure Island milieu as a metaphor for either Thatcher’s England or the capitalist world in general.

STEADMAN: I don’t think I’m that parochial that I just think of Thatcher’s England; I try not to think of Thatcher’s England. It’s just life generally, isn’t it? We’re on the same planet. There are different states, different circumstances, but somehow basically life is the same. It has the same kind of struggle within it, a built-in struggle from birth to death. If you think on an international scale, a global scale — you have to think like that now because it’s pointless thinking simply of your own backyard; it’s everywhere, somehow. We’re all in this thing, and, as I said earlier about the Third World, it’s got to be coped with; it’s got to be dealt with in a way that might make it possible for East and West to coexist, but I don’t know how we’re going to deal with the tidal wave.

GROTH: Do you think it’s axiomatic that excessive materialism brings with it a certain kind of spiritual debasement or displacement?

STEADMAN: Yeah: a bankruptcy. Definitely. You see, I feel at the moment the world is just beginning to emerge from its first era of true materialism only to find a new one just about to emerge in the Third World, which is going to demand equally and probably more so — who knows? I mean, they will have learned things from the West — a tidal wave of new materialism, which will be the hallmark of the 21st century. That’s probably what we’re about to suffer — or experience; whether we suffer it, I don’t know. So, I think that’s what the 21st century’s going to be: confronting what might be either the last vestiges of the old world of idealism — I’m talking both of social idealism and political idealism: the social idealism perhaps represented by the people we were talking about earlier, the Greens, and the political idealism represented by the old-style, unionized people, union members, union leaders, socialists of the old school. They’re very definitely beginning to display themselves as a different breed. If you stand back from all this and watch these people, you can see them operating on levels and around subjects that are somehow already defunct. The demands they’re making for their members are probably not what their members want at all, but, still, the pressure is there to be the union leader and to go through the motions — and it’s that going through the motions which is so obviously habitual. It’s difficult to tell a dinosaur that he’s extinct: he’s still got to live, hasn’t he? And he can’t retire. Perhaps he’s a bit too young for it; there are a lot of those types around who are still part of the old school. They’re straddled, you know? They’re trying to make sense of a new technological world, and they’re also holding on to what they were brought up to believe as kids, that this new socialism is going to alter everything and make their lives better. That’s instilled; you can’t even kill that with reason and logic.

GROTH: Do you think that socialism has adequately addressed itself to the problem we were talking about, of a cultural and spiritual bankruptcy that stems from our economic emphases?

STEADMAN: No! It simply hasn’t! I think what it’s done is that it’s forgotten the very things it originally stood for, which wasn’t just making money. The main thing it stood for was everyone’s right to a roof over their head and food to eat. That was the basic premise for having socialism at all: a kind of equality; everyone has that basic right, if nothing else. What was then forgotten in the scramble for a better way of life — so far with a small “B” — was the spiritual side of life, the other interests that enrich your life, and, in fact, I haven’t in the last 20 years — I probably never have — heard a union member, a union leader, or even a socialist leader — or any leader of that ilk — speak about the spiritual side of life: that we want more for the arts, for instance, more for what we consider to be our leisure time. Our leisure time has to be an important part of our lives, otherwise I don’t understand what life is about — or, really, it’s just a scramble for more money which only equates itself openly with the rising cost of living as to what it’s worth. So you never actually get any further on, and yet they still play the same game. Everyone in the political field is demanding more, and so everything is cancelled out accordingly.

It’s time to enter politics! [Laughter]

GROTH: Immediately.

STEADMAN: It’s called “The New Age of Reason.” It’s a bloody nuisance. It is a bloody awful thing when you felt you were a socialist at heart, and all you hear is people talking as acquisitively as your rawest capitalists.

GROTH: That’s because socialists are addressing the problems on capitalists’ terms, right?

STEADMAN: Yes, absolutely. But, you see, even in Russia, it became more of problem for those who would think for themselves, and therefore the natural liberties were eroded completely, free thinking was forbidden, and Stalin finally stamped out the opposition, and the place became an impossible place for anyone to live, particularly an artist. It was geared to accommodate the least expectation of the poorest peasant. And whilst that’s laudable, it can’t be the whole of life or what life could be about. Communism’s history seems to have been about denial of any really interesting lifestyle, which is why I think Gorbachev is now at this point making desperate attempts to reassess that, to rebalance it without — hopefully — incurring the wrath of the smaller dispossessed Eastern European. There were those great pogroms, purges to get rid of various Eastern Europeans— mainly dissident Jews, refuseniks, etc. — eradicate them because they wanted to maintain their ethnic roots, and that didn’t fit in with the new communism at all. It simply didn’t because it’s too untidy to have people who think for themselves, maintaining their own traditions. You can’t do it with an ideology; you’ve got to plane off the top and get it down to a standard, get it down to a level. You can’t have bits sticking out all over the place; it won’t work with an ideology. So it seems Gorbachev — although he’s got such enormous old rear guard action pressing on him and then front guard action now from this new ethnic uprising — has got a hell of a job ahead of him. But in fact he seems to me, from what he’s said so far, to be an incredibly enlightened man. He’s having to move slowly, but at the odd moment you see him take a quick, deft move and shift things on. I mean, he’s quite smart at that, so I don’t know whether he’s going to pull it off or whether someone’s going to do for him one day, but I just hope he’s there for some years to come yet.

GROTH: What do you think the chances are of Russia embracing a Western materialistic ethos?

STEADMAN: The Russians are probably intelligent enough to realize that raw capitalism isn’t the answer, but a combination of useful elements: if they’re going to move towards capitalism, they’ve also got to really decide to maintain or re-encourage their ethnic minorities, their ethnic groups. Russia’s a big country; it encloses enormous numbers of weird and wonderful people: Mongols, White Russians, strange persuasions, people from different sorts of cultures, which, if these things disappear forever, will diminish the quality of people’s differences.

GROTH: There’s a conservative theory that you can’t have democracy without laissez-faire capitalism, and you can’t have capitalism without democracy. What do you think of that?

STEADMAN: You can’t have democracy if you’ve got raw capitalism, really, because you’ve always got under-privilege and privilege. You’ve always got that problem: you’ve always got the haves and the have-nots. Capitalism insists on it: there are those who will win and those who will lose. When it’s about winners and losers, you’re not really talking about democracy at all. The basic problem is one of avarice, human nature’s avarice, which is encouraged by capitalism. Call it a quality or call it a defect: whatever it is, avarice is very much a part of capitalism, and once that is encouraged as the basic premise for capitalism to survive and to flourish, then you cannot have the other parts; you cannot encourage the reason and the selflessness that would be required of members of the society who are trying to achieve pure democracy. You’ll never achieve it that way. The two are in conflict. What I’m saying is that it’s not really good for a world rich in monetary terms; it would never appeal to the average American at the moment, most of whom escaped from those very areas that were

stricken by what we look upon as poverty. I mean, the huddled masses went to America for the very reasons that I’m advocating, in that we should try to hold on to these ethnic beginnings, those things that were at one time facts of life, the richer side of life, the richer idiosyncrasies of life. We are entering a world, I suppose, where technology should be evolved and developed to simplify those things we really don’t need to, or shouldn’t have to, trouble ourselves with in order that we can get on with trying to enrich our lives. We’re really turning those into reasons for living, those very things, those objects, those computerized forms of existence; they’re becoming the strength of our lives. They, too, are in conflict with any kind of democratic ideal because they become pools of control. As I mentioned earlier, they’re part of the surveillance mechanism, aren’t they?

GROTH: Can you give an example of what you mean?

STEADMAN: Well, the taking down of names, places, people’s activities, and computerizing them, sending them around to places like banks, American Express offices, for which they can then pigeonhole us for various products and invasion by junk mail. And it’s a kind of controlling mechanism because they can work out our spending habits — and I say “they” because I’m talking about those people who have completely and utterly joined that capitalist hierarchy and are enjoying the manipulation of those others of us who are presumably looked upon as the gullible buying public. And that’s one form of technological control that has really gotten quite clever with the introduction of the circular letter with your name in the middle of it somewhere, as though the letter was addressed to you personally. I mean, that’s quite an insidious development, isn’t it? It’s now an old hat idea, but at least it was one of those developments which gave someone a head start and advantage over another in the attempt to subvert your own instincts or your own inclinations. Their attempt to subvert your inclinations is quite well served by a letter that, in a sense, flatters you and has your name in the middle of it, and in the early days a lot of people must have fallen for that. But at the same time, those names that they’ve got have come from central banks of names and addresses, and they know everything about you. It’s very difficult for people to operate now in a private way because we’re so well documented. It has its good points, I suppose, in times of earthquake and the like, finding out who was a victim and who wasn’t, things of that kind. Technology is good for getting messages to stricken places or rescue operations moving. All this can be done, yet I think there was an Italian town under siege from an earthquake recently and monies brought in somehow got diverted by bureaucratic processes which really are no longer necessary. I mean, so many places still have this bureaucratic bullshit which prevents things from getting done, even though now we boast of a world which is so much smaller now because we can get things done far quicker and can immediately refer to something. All of this could be good, but it is frustrated by this peculiar part of human nature, again, which likes still to hold the reins and make things awkward for others and to not use the technological advantages at all but to pretend to, perhaps.

GROTH: To abuse them.

STEADMAN: To abuse them, yes; to use them for what I said: the surveillance factor.

GROTH: Well, for example, would you object to your books being sold by sending these personalized letters to people?

STEADMAN: In many ways, I would, yes. In all ways, yes. A bookshop’s a place where people can browse and choose for themselves. What I would like to think — if they’re going to use things, they can at least use the methods that they have, these technological new ways to bring things to people’s notice, but not through people’s letter boxes. I do believe in some sort of privacy there. I don’t think circulars of that kind are too good. At least you can do them in magazines where people have the right to either buy or not buy a magazine and see an advert, or even to appear on a television or a radio show and talk about a book that you’ve done. That’s quite legitimate. It allows people the right to switch off or — I would like to see publicity-conscious publishers doing a little more for books and perhaps I wouldn’t mind them publishing less books instead of saying, “What are you doing next?”

GROTH: Oh, yeah, I’m very much in favor of fewer books being published. The forms of manipulation are so various, it’s a difficult to know where to draw the line, but you do know instinctively that the line has to be drawn.

STEADMAN: Somehow. I mean, there isn’t time to read what you want to read, let alone all the other books.

GROTH: All the worthless books.

STEADMAN: Yes, the books for no good reason sometimes. Modern fiction: a lot of it is really nothing at all.

GROTH: Have you seen a British film, How to Get Ahead in Advertising?

STEADMAN: Oh, that’s my favorite. A friend of mine, Bruce Robinson, wrote it. He wrote it and directed it. I’m on the credits even.

GROTH: Oh, you are?

STEADMAN: Yeah.

GROTH: I didn’t notice that.

STEADMAN: I did a drawing for him of it as a good luck thing for him when he started directing the film. It’s a brilliant idea. Would you like a copy of the script?

GROTH: Oh, yeah, I’d love it.

STEADMAN: Because it’s incredibly funny.

GROTH: I very much enjoyed the movie.

STEADMAN: Oh, it’s hilarious, isn’t it?

GROTH: Oh, yeah.

STEADMAN: At the end, I loved the last part, you know, about “England’s green and pleasant land” — “If they want their toothpaste with fluoride, I want them to have it. I want them to have their cows and, by God, they’re going to get their cows.”

GROTH: Yeah. I loved the last tirade.

STEADMAN: Yeah, it’s just a great film. Have you seen the other one by him, Withnail and I?

GROTH: Yeah, I did. I didn’t like that as much.

STEADMAN: Well, I think this one’s perhaps more relevant. I mean, it’s a very English him, the other one; but I think that one, How to Get Ahead in Advertising, should do very well in America. Robinson’s a very interesting guy; he wrote The Killing Fields as well.

GROTH: Oh, that’s right: an excellent film about Cambodia during the Vietnam War.

STEADMAN: It was interesting how he was able to do it, because he hadn’t been there. He’d read and thought about it a lot and got the nitty-gritty.

GROTH: Now let me ask you this: do you think a film like that has any real effect on the audience? Or is it preaching to the converted?

STEADMAN: In a funny kind of way, it does because what he’s doing is advocating a worse world — if that’s what you want. In fact, in some ways it shocks people more, some guy actually advocating worse: more of this and more of the other, more consumerism. You know, he’s actually advocating it, and it makes it funnier. It makes it also more shocking, so in that way I think it could probably work. It makes you feel ashamed.

GROTH: Paddy Chayefsky’s movie, Network, was somewhat similar in its cautionary intent, but I don’t think it had an appreciable affect because it’s now being shown on network television. This movie that criticized television in the most uncompromising terms is now being shown on network television and used to sell dog food.

STEADMAN:[Pause] Well...

GROTH: Sorry. It’s an unpleasant way of looking at things.

STEADMAN: Yeah. I don’t know what Robinson’s doing at the moment, whether planning another movie, or of what kind. He’s forever tortured about what to do. It’s the worst kind of thing in the world, trying to be creative, particularly in a pointed way.

GROTH: We can only hope that he keeps making movies.

STEADMAN: Oh, yeah. I hope so—and also directing his own, because he knows what to do.

GROTH: We’re right in the midst of a summer of absolutely shitty films: mindless, multi-million dollar blockbusters.

STEADMAN: Oh, yeah. [Laughter] A lot of them about.

GROTH: Has England succumbed to Bat-mania?

STEADMAN: I’m afraid it’s happened, yeah. You know, we’ve had the hype, and now the film is coming. Apparently it’s grossed more in a weekend than any film in the history of Hollywood. Is that right?

GROTH: Yes. It’s an ugly phenomenon.

STEADMAN: Yes. It really is back to the tittle-tattle for an escapism, which — parts of it are excellent, but parts of it are pretty hideous. It sort of shows the tackiness of our aspirations right now, to be so desperately keen to see such a thing.

LOSING FAITH, FINDING INSPIRATION

I still find that the line is still the most expressive artform of all: to think that a white sheet of paper can contain so many variations of a line going somewhere, wherever it goes in the system. To me, that’s the most complex computer you can imagine: the white sheet of paper. There’s nothing on it. And if you think a computer could hold within it all the possibilities of a human being, any human being — and there are so many of them who want to draw, coming to that piece of paper and figuring out what’s going to go on it before it appears. It seems to me that that white sheet of paper is the infinite in possibilities. It’s those ideas that are going through my mind as I wonder what the hell I’m going to do next.

The God thing [The Big I Am] is done now. It left me a bit empty. What do you do now? I can’t, for instance, do political cartoons in the newspaper any more, because I feel like I shot past the bus stop and I didn’t stop to see if there’s anything there. I went past the bus stop where I should have patched up. I don’t know if this is an analogy of anything, but it seems as though I stayed on the bus and nobody else got on and I went a bit further, and I’m somewhere else and feel as if I’ve gone somewhere that maybe at the moment it’s difficult to use or harness in some form other than in a book of my own making. I couldn’t, for instance, use God-like drawings — the God style of work. I feel as though it’s the sort of thing that can only be used in the context of the book I’ve done.

In fact, I don’t think I could even draw like that if someone said, “I’ve got this article here; will you do it in the God style?” because it has to be about my subject that brought that out, that way of drawing, because it’s different from the America book, isn’t it? It’s quite a different feel.

GROTH: Well you say you couldn’t go back to political cartooning. How do you mean that?

STEADMAN: Well, I mean that I’m not interested in political figures. I think I’ve blown it with them. I think I’ve shot my bolt. That was awful, but I feel as though I have. I’m not the slightest bit interested in Bush or Dukakis; when I try to look at them, like I looked at them today, I don’t really even want to pick up a pen and draw them.

GROTH: You don’t think it would do any good?

STEADMAN: Yeah; I believe it won’t. It certainly won’t do any good. It did seem to me today when I was looking at those two that I mentioned — it was like they were discussingevents after an accident, and the accident had been the terrible mess the American economy was in, the American foreign policy, the Contra problem, all those things. And these two were discussing their accident as though they were part of it, but that they were really — in fact, George Bush said on this thing today, “If you’ll just forgive me those two things about selling arms to the Contras,” he said, “I’ll take the blame for both those things: Iran-Contra and Oliver North; I’ll take the blame for that if you’ll just give me credit for all the good things I’ve done since I’ve been in office” [laughter] You know: the peace and all the things he mentioned. That’s what he said. Well, it’s such bullshit.

GROTH: You don’t feel compelled to puncture that bullshit?

STEADMAN: No, because I think the more you go for it, the more it seems to lend credibility to these people. I’m sure it does. I’m sure it’s wrong to criticize these people in such an important way, to give them the benefit of your attention.

GROTH: But isn’t there a sense that you’re giving up?

STEADMAN: Well, maybe I am, but maybe I’m trying to find something else to do. You think, “What should you do with the other part of your life?” I’ve done that for 30 years, and the world’s in a worse state now than it was when I started. I’m supposed to have been able to put the world right, and it’s worse.

GROTH: Of course, it could’ve been even worse yet.

STEADMAN: That’s right: I could have sort of held it up a bit. You’re one of these goddamned optimists.

GROTH: [Laughter] That’s the first time I’ve been called that. You went through a crisis of faith vis-a-vis cartooning several years ago.

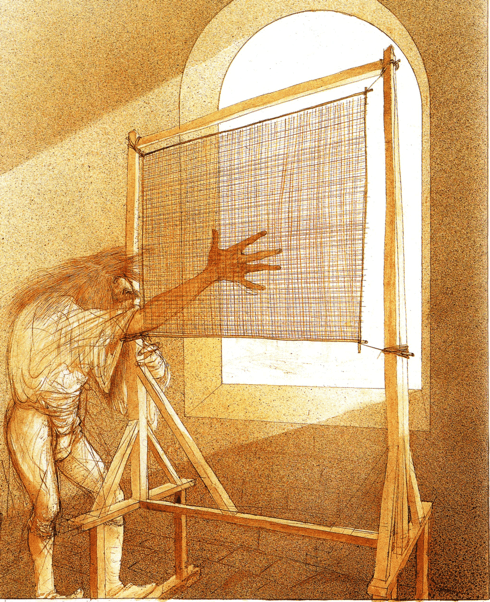

STEADMAN: I’m always doing it. The self-doubt is shocking. I’m continually doubting my ability to draw; I’m continually filing a project that is sufficiently stretchy to get involved in, and actually stretch myself to the point of inspiration. And if there isn’t any of that in it, I can’t draw any better than anyone else. But if I get that thing that gets me going like Leonardo did — and the God thing has as well, and some of the American drawings in the Scar Strangled Banner, and also the original America, and some of the things Hunter and I have done together — stretch my mind in a certain way that I was able to draw like a bastard. It just came out, something which I couldn’t create everyday. And that’s a bloody situation to be in because you’d love to be able to go into your studio every morning at nine and know that by five o’clock you’ve got a thundering good piece of shit on your board, something that really laid it on the line so that you’d had the feeling that you wanted to fill a space every day, every day was a thunderer, a real son of a bitch that really gave people a bad time. It’d be marvelous. But I know it won’t, because I haven’t got that kind of interest or desire to do it. I mean, maybe it’ll disappoint a lot of people that may consider themselves to be some kind of fan: “Aw, shit, he’s given up.” But it’s too bad in a way because it’s no good going on repeating yourself. I’ve felt I’ve done some good stuff now. You see, if I lay off it for a while, maybe I’ll get interested in it again, when I’m curious. So I’ve literally laid off cartoons for a while and invented this whole idea that I only want to lay off it because I want to ignore them because it’s better for me. So, that’s my invention.

GROTH: Considering how much you’ve done and how much of your career has been political, it’d be hard to believe you could stop doing it.

STEADMAN: Well, stranger things happen.

GROTH: And it’s obviously a passion for you.

STEADMAN: It was, partly because I believed things could change. I believed there was a cause worth fighting for. But it doesn’t seem like that; I think everything’s been squashed again. And everyone was self-satisfied and smug in America in the ‘40s and ‘50s — you know: America was great. Fifteen years after the war must have been a wonderful time for Americans. They were so full of themselves; he was working, everyone had a car — you know: American Graffiti. It was a time of happy days, full of a sort of very American smugness. And it was working until somebody decided to see the cracks, then the time of change of the ‘60s which led people to believe that it was going somewhere. Unfortunately, running parallel to that was the stickier involvement in the Vietnam War. Foreign policy wasn’t giving them such a good time. They suddenly became an imperial power in the sense that they’d got themselves stuck in a place that even not many Americans knew where it was. You know, suddenly they find themselves involved in it. Suddenly, they found their lads going out to this godforsaken place — probably a nice enough place for a holiday for two weeks, just a change of scene, not when you’re suddenly stuck there. And that’s harrowing: the American sense of well being. At the same time there was this extraordinary rebirth coming in the form of flower children and hippies and of course Kerouac and that crowd — Ken Kesey. Of course, then you get bloody prophets like Timothy Leary, who made everyone think that all you’ve got to do is turn on — simply, purely as an escape. It won’t solve any problems. And these people were somehow running the show.

Yet the kids were so hopeful that it was for a real purpose: commune living, free love. Of course it was super: no responsibilities, rock ‘n’ roll, turn on — and forget. Just forget. Get involved in your own thing.

As the Vietnam War got uglier, the rest of the world began to exert itself as the media seemed to increase its clarity and objectivity: people could no longer turn away from things; they were looking at TV screens that were giving them information that they never had before — there was a world out there. It’s like inventing the H-bomb: you couldn’t suddenly say, “OK, let’s uninvent it.” You couldn’t uninvent the media, either. You couldn’t uninvent the fact that we got to know about things. You couldn’t suddenly forget it: it was too clear. And no matter how much we kept saying, “Well, you see these people blown up and you see all this happening and so forth, you see the poverty and the terror and everything else happening,” you get used to it after awhile and your mind switches off. But in fact you can’t completely deny it. So, it’s a trouble in the back of the mind. Then you find people going down weird streets to try to pretend there’s a purpose to their existence, to appease their sense of guilt, and gradually it eroded away this free-thinking where, “Hey, man, everything’s OK.” You saw the young beginning to talk about responsibility again. I think that came from this other strange awareness that things were not good abroad so therefore maybe we should clean up our own moral act, try to become morally conscious again, develop a new code of behavior.

But of course it was no accident, I suppose, that that started to happen at the time that the AIDS scare came. Our moral turpitude has become apparent over the last two or three years. Some find themselves unable to be as free and easy as they thought they could be before, and it’s then reflected in things like smoking. People don’t like people smoking anymore; drinking is getting to be a problem; and there’s all sorts of little attempts, I find — pathetic attempts on the part of a rather disillusioned generation to pretend they’ve got a genuine good purpose in life. They’re structuring their lives to attempt to face the truth of the 21st century. I’m rambling a bit, but I’m trying to get to the point of something: that perhaps makes me not want to do cartoons any more because I don’t believe that it’s going to change anything, and I also believe we are beginning to enter the last years of something which is damn near over. Well, we know we are; we’re just about to enter the last decade of a millennium — a thousand years! The party’s over, in a sense, and funny things happen to people in the end of centuries or periods. There was a little more hope I should think at the turn of the last century because most of the world hadn’t got anywhere; there was still a lot to do, and we somehow have spent this century exploring this world of ours and realizing that we’ve gone around in a circle and that we’re also destroying the bloody place, too.

So what are we going to do about it in the 21st century? Is it going to get worse? Technology: is that the answer? You can’t go on forevermore. They’re cutting down the rainforest because they need the land for developing and they need the wood for paper, more media print, more magazines, more this, more that ... And all these things are exacerbating our attempts to create a better world. Now, a politician wouldn’t talk like that. A politician would say, “Hope for the future! We must all pull together.” Bush was saying all these things today, and I was thinking, “Bullshit!” But am I wrong to think like this because I’m being utterly and hopelessly pessimistic? But unless we change, I don’t think we are going to get any better; I think it is going to get worse. At the moment, I see a kind of blackness beyond the year 2000. It’s either a lip or a stone wall — I’m not sure what is at the end of a century, and I can’t quite see over the top. I don’t know whether you have a mental picture of a century. Can you see 1910? Well, I have a mental picture of those periods. It would be interesting if one could draw that mental picture. I mean, we try to draw other things ...

GROTH: To encapsulate it you mean?

STEADMAN: Well — ”This is how I see it; this is what it looks like.” And if you could put in the bits that you can see in your mind, try and put them in a position so that when you finish you have a panoramic view of the century.

GROTH: Do you see the ‘60s and early ‘70s as a period of hope?

STEADMAN: I was full of it; I thought people were getting nicer. Well, they were getting nicer.

GROTH: What did you think was going to happen?

STEADMAN: I thought we were all going to get into a marvelous time when all the old values of pious self-righteousness were going to disappear and people were going to he honest with one another; people were going to generate goodwill amongst themselves because they were beginning to trust each other and they weren’t going to tell lies and they weren’t going to cheat and swindle and shit on everything. But it didn’t happen. People have now become as acquisitive and as greedy as they probably ever were, if not more so, because the opportunities are there to turn every one of us into these beasts of acquisition. I know I sit in here; I live in a big house. But as a matter of fact it’s a modest big house in a funny sort of way because it’s not opulent; it’s not dripping with anything because I haven’t got anything. What we’ve got is very modest. It just happens that I luckily got this house because nobody wanted it; I bought it cheap. Any reason that I’ve got any money is that this house is worth something now in terms of real estate, but I didn’t say, “I’m going to get the house and make a killing” I thought, “What a place to do Leonardo da Vinci! I have a lot of space here so I can fiddle around, build a flying machine and test fly it in the garden.” That’s what I wanted to do. I think so many young people today think they can make money out of nothing. That is, they play the market ...

GROTH: Some of them are making money out of nothing.

STEADMAN: I know they are.

GROTH: What social mechanisms did you think should be put in place that would forestall the inevitabilities that have overtaken us?

STEADMAN: Well, I think there’s too much emphasis on repression again, and I think we feel that if we repress people who smoke, repress people who break rules and regulations, that we’re going to have a better society. I think we’re going to have a sicker society on that basis. We’ve got to start teaching in the schools — that’s where it begins — a little more about the understanding of coexistence, how you’ve got to live with somebody next to you; you’ve got to appreciate that person’s desire for freedom as well as your own desire for freedom, and that if you take something of his that doesn’t belong to you it’s not just dishonest, it’s painful to somebody. It’s got to be made quite clear to children — and it can be made clear to children — you don’t do that kind of thing. Particularly, at the nursery school, kindergarten places — that’s where it really starts, you see them going for toys: you’ve got to try and teach them you can all have a turn here.

GROTH: You want to institute a different kind of repression — you want to repress certain acquisitive appetites?

STEADMAN: Would that be what I’d be doing by trying to get everyone to say, “We can all have a turn here if we just work this out”? “What we’ll do is we’ll have a hat with numbers in it and you’ll all get a go — you’re first, Johnny.”

That’s what my wife Anna’s doing in a book she’s writing called The Vanishing Estate, using her experiences as a nursery school teacher teaching kids under five years of age, from three to five. And she finds that they’re like little grown-ups in a way, but it’s raw: if they want something, they want it; they go and get it. Well, that rawness is part of adult life. If people want something, they just go and get it by any means; it doesn’t matter what means, and that’s so prevalent now that it can only be wrong; there can only be something about it which ultimately will cause pain somewhere. For instance — I’m talking about Britain now — Maggie Thatcher has almost exploited that sense of acquisitiveness and greed. It seems as though this government has created a climate where it’s necessary to be like that, and I don’t believe that is right. I think there are simpler moral values which we’ve got to reacquaint ourselves with. That’s nothing to do with rules and regulations; it’s just simple restraints on our appetites.

GROTH: Thatcher’s social philosophy, I think, is that by encouraging the impulse of greed the country creates a greater abundance for everybody.

STEADMAN: Yeah. Well, that’s what she says, but what she does is create a rather unpleasant attitude in people. I think that comes first, and I think it’s an un-Christian attitude, though she claims to be one. Now, I’m not talking about Christianity in the religious sense; I’m talking about it as a moral outlook, a moral yardstick. In her society there is no question of right or wrong: she has created a society of winners and losers; privilege can be bought and money is the only passport recognized. The rich and poor have widened and the have-nots are finding it increasingly difficult to improve their lot because the stakes are higher, the game more ruthless and the attitudes therefore brutal and desperate. To be a failure is, in fact, to fail in a financial sense, personal integrity does not enter into it. As one young man put it, she has made us aware of success. He meant that financially. What kind of human being he may be is immaterial. There have been some pretty good ideas about how to overcome our basic desires — not repress them, not deny them forever — but develop some kind of ability to restrain ourselves at certain times. Maybe that could be taught. Does that turn one into a repressed person? I ask you because I’m only talking about it. You may say, “This is a bunch of shit; of course you can’t get people to do this kind of thing because it’s just not human nature.” We’re also born with this extraordinary bunch of forces within us like nature itself: the sexual urge: the desire to eat and therefore to become greedy, greedy in all ways, they’re all there. They’re actually unharnessed, all of them — a baby just cries out for this when he’s born. So, unrestrained can get completely out of hand. If you know Lord of the Flies ...

GROTH: Well, it was actually a conservative political philosopher, Burke, who said something to the effect that we can become prisoners of our own appetites.

STEADMAN: Yeah, well, this is what’s happening now.

GROTH: Which is actually more repressive because they are pursued and sated and pursued and sated at the expense of the other, higher, more fulfilling values.

STEADMAN: Particularly when you suddenly find that you can’t get these things satisfied; that is the prison, isn’t it? It’s practically like the graph on the progression of a drug addict: the more he takes, the worse he feels.

GROTH: It’s a bit of a paradox, because conservatives are usually pretty big on limitations, like sexual or social constraints, but they place no restraints on the economic life.

STEADMAN: Well, maybe they channel it all to that, to the hunger for money: all the sexual appetites become money, they become placebos for money, money placebos. That’s probably what it is. I know that for some reason they don’t like the arts, anything that smacks of an uncontrollable freedom —that is, one that they cannot put a regulation around. You see, they cannot put a regulation around imagination. It seems that the one place we can still expand in this world is in the mind.

GROTH: That’s because they know the price of everything and the value of nothing.

STEADMAN: Yes, that’s right. Yeah. Is that Oscar Wilde?

GROTH: If it wasn’t, it should have been.

STEADMAN: I think it was, actually. He said a lot of lovely things. Somebody said recently, “I suspect that Oscar Wilde was always right.” [laughter]

GROTH: How absolute a critic are you of capitalism?

STEADMAN: Well, I realize it to be necessary to have some kind of healthy competitive economy, but I do believe it should be based on producing something rather than making money out of nothing, speculative money-making, which is just playing stock markets. We’ve created an emptiness were people claw their way around and make fortunes and lose them. This empty thing — I suppose it’s a graven image. I see it as a land of a weird dripping ball, like an obelisk or something, some land of spice which you can’t quite get to the heart of because it hasn’t got a heart. It hasn’t got anything inside it.

GROTH: [Laughter] Well, since we’re talking about Thatcherism, tell me: how do you think it’s possible for someone to earn more than he deserves in a free-market economy?

STEADMAN: Well, by getting away with selling rubbish, whatever rubbish is — tacky crap. People buy and sell the cheapest stuff: muck. They make their living out of it. There’s lots of toy adverts on television I see — selling ridiculous garbage for kids. You can imagine that the person behind it is some fat, greasy, suited individual who’s making a lot of money, doing cutesy things, creating cutesy things that make you go “Yuck!” and they’re making a lot of money out of it, and they’re giving kids false values with that — pink donkeys and things that are too cutesy for words, and they’re so awful. Funny how we don’t even know why they’re awful.

It’s interesting to look at houses in England, and they still make houses with roofs and two windows and a door down below; regular house; the kind a kid draws. They were making those a long time ago, last century and before, back in Tudor. They may be unpractical but they’re so superior to some of the modern ones — but I always look at the modern houses and say, “What makes them so bad?” Where has that atmosphere gone? Something has disappeared. They bring the window to the front of the wall, rather than leave it set back: that presentation of the window gives a sense of importance to the wall. The window set back into the wall, from the weather point, weathers better. Those are very simple things, but now they bring the window to the front of the wall for some reason. It’s an architect’s daft idea, and it does something that’s wrong. I don’t know what it is that makes it wrong, but it’s wrong.

GROTH: It occurs to me that conservative and capitalist economists or apologists don’t take into account the kinds of value formations that you’re talking about.

STEADMAN: No, because it means less profit.

GROTH: But it also puts people such as yourself at a grave disadvantage, because everything you’re talking about is not provable, in any empirical sense.

STEADMAN: No, because you can’t prove — you’re not going to convince a man whose interest is money. What you’re suggesting would be better for the people he’s milking it for, because he’s going to make less profit. What he’s thinking about is profit margins.

GROTH: That’s right, because you can’t quantify your argument.

STEADMAN: No, not at all. But I think, ultimately, if one did carry it out, if there was such a philanthropic man around — if he was making lots of houses for lots of people, he could create new communities. Communities these days, as a rule, are horrible. They have no spirit, no soul, no center, nothing, just laterally placed. And we get nothing but basic necessities, at quite a price. There should be — one day there will be — a philanthropist who would like to prove that you could build cheap houses for people and have a pleasant feeling. Some nice things. You could landscape the place and make people want to live there. You could ask 99 percent of the people why they like living there and they’d say, “Well, it’s just nice.” They wouldn’t know why. They wouldn’t realize that what they’re doing is exercising an aesthetic judgment, naturally, native. It’s like the animal’s instincts.

GROTH: But that isn’t likely to happen insofar as people are quite content living in prefab houses, is it?

STEADMAN: Well, I don’t think they are. They got no choice, that’s all.

GROTH: But middle-class America doesn’t seem terribly displeased with living in suburbia.

STEADMAN: No, but if you give them a choice, they’ll adapt to something much more aesthetically pleasing. I think they’re equipped for it. People don’t have any choice really now.

GROTH: Now, why do you say that?

STEADMAN: The things we’re talking about: the unpleasant, the normal, is the standard; the standard is rather low. The standard is being accepted more and more, in a broader and broader sense, by everybody. More and more people are putting up with less, and by putting up with less, they are conditioning themselves to accept that.

GROTH: Do you mean less spiritually or materially?

STEADMAN: Aesthetically. Spiritually. It’s difficult. I can’t divorce the two sometimes. And if you have to ask me what spirituality is, or aesthetic response is, then I can’t tell you, because you have to ask the question.

You know: it’s like asking what it’s like to express jazz. It’s the same kind of thing, and I think all animals have it, because why do various animals have certain habitats? They have it because it suits them. If the rat likes living in a sewer, it’s because it suits him aesthetically; the sewer’s a perfect place for a rat.

GROTH: Would you disagree with the proposition that people seem to feel fully compensated for the absence of the spiritual by greater material gain?

STEADMAN: Well, yes, but they’re not, are they? And they know it. They get unhappy; they get divorced; they give their fat kids a bad time; they somehow seek other kinds of pleasure at the expense of their kids.

GROTH: Yes, but they muddle through.

STEADMAN: Muddling through is one way of living, isn’t it? Is that how far we’ve come in how many thousands of years of civilization, to muddle through? I know there’s no slavery, but there is in a way; we’re all slaves in that sense. But if that’s how far we’ve come, then that’s not saying much. And although it’s no counter-argument, people seem pretty content with that. I just think people shouldn’t stop there; they should be constantly striving for something else. Aspiration is about the only thing we’ve got to maintain some forward movement.

SPIRITUALITY IN ART, and MORE POLITICS

GROTH: Two pieces in your book Between the Eyes were acute criticisms of capitalist civilization. One was “My Drawing Grouch,” and the other was “Money, Money, Money.” I’d like to ask you about them. In “My Drawing Grouch,” you wrote, “We” — meaning “we artists” — are declaring ourselves non-rational beings, i.e., people who intuitively act upon impulses without rhyme or reason.” You go on to say, “We are only necessary when we as artists can be seen to be exploiting an intangible flare in a way that brings us gainful employment within the system.” By which we’ve already agreed that you meant that artists are seen as gainfully employed once they lock themselves into the utilitarian economic system.

STEADMAN: They do so when it’s needed, on a very practical basis. The spiritual side of any person’s output is completely disregarded as an unimportant factor. It may be that people will indulge us: “How very sweet.” They give you a pat on the head: “Pretty line,” or “Pretty color you put there; how nice that is; that’s sweet; I like that.” But they forget the spiritual, the motive side of color, line, and the way it’s put together, and the effect it can have on that inner being. That’s the most important thing, but people forget that. Actually, they are evaluating everything in terms of money. If it doesn’t have a price on it, they can’t figure it out; it makes them nervous. They need to feel the practical effect of money on something; they need the necessity of a figure that seems to give them an idea of how much they’re going to like something, and how much they’re not going to like something. So it’s always a funny thing, but it’s better to charge a hell of a lot more than you think anything’s worth for people to get their value out of that — say, if you have a piece of paper and you think, “Well, I’ll say it’s $5,000.” Well, if you think I’ll pay $5,000 for that, that’s some piece of paper; it’s pretty special. It’s only worth a pound-two dollars — for a sheet of paper, which it is in fact in the utilitarian society. Whatever price you’ve got on it a piece of paper is worth two dollars. That’s what I mean if I’m looking at things from a monetary point of view. It’s simply by that measure; that’s all we think of things: how much it’s going to cost.

GROTH: Can you expand upon what you mean when you refer to the spiritual?

STEADMAN: I don’t mean it religiously, except in the primitive tribe, yes, “spiritually” meaning “religious.”

GROTH: But you don’t mean it in a precisely religious or theological way?

STEADMAN: Well, not in a theological way; I don’t mean the state and the church combination. So you’re referring to the spiritual almost in secular ways. Or is that a contradiction? No. Spiritual can be the feeling you get — I mean, it’s the difference between good and bad. That good feeling you get is a spiritual feeling, isn’t it? It’s not just a physical one. Sometimes you feel very good just because you really achieve — you’ve reached out, aspired to something and perhaps achieved it — and you can’t necessarily measure it, you can’t quantify it by giving it a nine out of 10. It’s just something you feel because you set out to convey something, to communicate something. And what you’re really doing is communicating a spiritual feeling about something. When I did the Leonardo book, I tried to communicate a sense of the man, his soul, his being, the way he felt, how he was, and watch the world from his point of view. In some respects, I feel I succeeded, and the measure I put up is how good I felt when I’d done it. That’s how I know I can measure it. I can’t say, “Because it made me x-thousands of dollars” or something. That wasn’t it.

GROTH: I assume you would contrast this feeling you’re talking about with mere happiness. You’re not talking about being happy.

STEADMAN: Well, in some ways it is. It’s a terrible thing to be depressed. I get depressed a lot.

GROTH: But it’s more than that.

STEADMAN: Oh, yes, it’s more than that. It’s that thing we’re trying to disregard with our monetary way of looking at things. It’s something very personal to each of us, but that we are denying in ourselves. As the red Indian said, “The white man is fucked. He doesn’t believe in anything any more” — because the red Indian still believes in certain powers of certain objects, in animals, in places that have spiritual meaning; it’s to do with himself and his position in nature — just as the aborigine doesn’t own the land, the land owns him. And it’s a very spiritual relationship. So they have this respect for certain places, where they identify with a particular animal, and that animal they will not hunt because they identify with it. And I find that’s just what we have lost.

GROTH: Do you have a theory as to how the spiritual has been usurped by the economic?

STEADMAN: Greed. Pure greed. Raw greed. We decided that we can get more happiness out of buying a crate than we can by going and taking a walk in the woods, or buying a pool sweep. [Laughter] I’m part of it too, you know, but I know how much of a temporary thrill it is buying anything, buying a new tape recorder. For a while, it’s a toy and you enjoy it, but after a while it just becomes a tool you use. It’s good when you get to that position: you buy it because you want a tool to use, for work. And I like machinery for that reason: it’s useful to me. But it’s usually got to be for an expressive reason.

I feel very strongly about that. I will impress upon you that there are only expressive reasons for having anything: it’s for communicating with the outside world. Your particular stance is expressed this way, whatever it is. You might be a good shoe salesman, and you express yourself by selling shoes in a way that gives people pleasure when they go to the shop. They actually don’t just buy a pair of shoes, but they actually had an enjoyable passing of the time of day when they were with the shoe salesman. He is doing a good job of that. A good waiter can express himself marvelously; he enjoys telling you what’s on the menu; he goes through the whole spiel for you, telling you what’s coming, and there’s a great sense of selfless joy in that. They want that. It’s not just saying, “I’m charging you $5.95 for this, and $6.00 for this.” That goes without saying: the price is there; the extras are the things they do for their pleasure as well, and — are the spiritual things. I mean, the good atmosphere. What is an ambiance? What does it develop as you walk into a room and there’s an ambiance, an atmosphere? Why is it that sometimes you’re very unhappy in it, and sometimes you respond to it and love being there? Why does it put your mind at rest, suddenly? And why is it not sometimes, when you’re somewhere else? Like at LAX [Los Angeles International Airport] or something, standing waiting for the cab, or you’re waiting to get your baggage back — and how bad you feel. You feel threatened and generally unpleasant, because there’s nothing else there to reassure you; it’s a brutal scramble to survive. And so, I think, they’re all spiritual experiences, and that’s why I believe it’s in everything we do.

If we have to have these utilities — which we do — there’s no reason why we can’t buy them for what they are, and get pleasure out of them sometimes because they’re new. But then it’s what you use them for ultimately. It’s lovely when you get a nice drink; there’s something aesthetically pleasing about that, or about putting a glass into the freezer, getting it cold before you put the cold drink in, too. The Americans are great for doing that, but that is an aesthetic reason, you know; it’s something —

GROTH: All things aesthetic turn into commodities, though.

STEADMAN: Well, that’s OK, but people are then beginning to deserve the monetary success that comes with doing it the right way: the nice shop, the right atmosphere, the right kind of things, the service that comes with it, the good products. There’s nothing wrong with that at all. I just think that for their own sake they are wrong, when they’re the be-all and end-all of life, of all things. So then that denies every other consideration, aesthetic or otherwise, once it starts with “how many, how big” and how rich you got.

GROTH: In your article, “Money, Money, Money,” one of the things that you say is — well, of course, the common wisdom is that we use money. But you turned that on its head, and said money uses us. How did you come to that formulation?

STEADMAN: Just by reversing everything, like Lewis Carroll did in Through the Looking Glass — reverse everything and it takes on a sort of extra meaning, because she’s gone through the mirror, she finds that she has to run twice as fast to stay in the same place. It changes the meaning entirely, you know, when you run away from a mirror. That’s a wonderful thought.

GROTH: It’s almost an obvious insight, but it’s an insight that people are resistant to.

STEADMAN: I don’t think people like to be looked at as greedy or feel as though they are greedy. You can say to someone, “You’re a greedy pig.” They are, you know, but they don’t like to do that; it’s kind of an insult. But they are being exactly that, and the people that drive up here [to the St. James Club], a lot of them you could go up to and say, “Good morning, sir, you greedy pig; you’ve got more than you deserve.” If you said that outside the St. James Club, you’d probably end up with some kind of fight. But it’d be the truth — even if I’d walk up to everybody actually. In restaurants, they’ve got far too much on their plates, as you do in America. You could just say to everyone, “Good morning, greedy pig. Have a nice day.”

GROTH: You mentioned Lewis Carroll. You illustrated Alice in Wonderland in 1967 and Through the Looking Glass in ‘72. Did those works have a special significance for you?

STEADMAN: I’d never read Alice in Wonderland, never had it read as a child or anything, and so I read it and found it to have such extraordinary parallels with present-day society — I mean ‘60s society as I thought then — that I decided to make it a kind of a transplant and look for present-day parallels so that the White Rabbit became the modern commuter, the crazy-eyed commuter going to and from work every day on trains, worrying about time, going nowhere in particular. At the time, it was a very English parallel; it wasn’t really a universal one. Let me see. Well, some of them could be American. The Mad Hatter to me was a TV quiz game show host. You know: “Come back and make a fool of yourself next week!” — that kind of character. The Cheshire Cat represented the TV announcer who smiled a lot when he said anything, and whose smile remains after you switch the television off. We had one called Cliff Mitchelmore whose smile seemed to be there when you switched off — very strange kind of thought about it; so that was the Cheshire Cat. The cook with the Duchess was a sort of Fanny Craddock, a TV cook.

Things that we look at, new imagery, seem to relate to some of the characters that Carroll invented himself or found himself in Christ’s Church, which is what he wrote about in the book.

It was really for me a move from doing Private Eye cartoons, which were sort of social comment, to using the same approach in the illustration of a story. So that was the real beginning; that was the real reason for it. I realized that illustrating books didn’t have to simply be a secondary role for an illustrator: it could become an important aspect of the book, an integral part of it, so it was always with me from me the beginning. I was bugged by the idea that the writer always got the best position. I wondered why that was, and it’s mainly because the illustrator has always simply filled the odd space to relieve the text. That’s been his fundamental role, not really to enlighten or to add another dimension — I mean, a thoughtful dimension. It seemed to be something which left me feeling rather empty and ill-used, shortchanged. I felt that there was more to it than that because drawing is so expressive: “Why can’t I use the words merely as a springboard for my own ideas?”

GROTH: So you saw it more as collaboration?

STEADMAN: Yes, that or merely use the words — particularly a classic. If you wish to illustrate a classic, use the words as a springboard for your own ideas: “I agree with those ideas in the text; how can I express them?” Then I did Alice Through the Looking Glass. At the time, I was living in a flat in Chelsea, and it was full of mirrors: there were about 20 mirrors in the house. It gave me the whole feeling for that reflective quality that Looking Glass is all about, and I used the book itself as a kind of mirror image of itself: halfway across the page would be the change in the image. Then, of course, it evolved into a desire to write my own words and express them visually as well. So, writing began slowly, and in a little bit of time I did a few things like “Gardening Notes” and the like in Rolling Stone and I realized I quite enjoyed writing. I thought I could be a writer, but somehow I’ve been told that I wasn’t a writer because I hadn’t declared it early enough, so therefore my pigeonhole was to be an illustrator or a cartoonist or something, who had to by the state of things adopt a minor role. It sort of bugged me a bit; I thought, “What is so special about writers?” I’ve met some who are real assholes, you know?

GROTH: [Laughter] Right.

STEADMAN: And yet they’ve got a better status than me because they’re called writers and I’m only a cartoonist, and there must be lots of cartoonists who feel the same as me. They’ve got a kind of intelligence, and yet they’ve been shortchanged all the time by social position in the scheme of things, even something as bland as that. Somehow in people’s minds you associate a cartoonist with someone who either does it in his spare time or didn’t get a very good education and therefore scribbles and does a few gags, and cartoon magazines are very down-market. I thought, “Well, fuck this. This is just what they like you to think.” So I really found all those things irksome to me, and, really, ever since I’ve gone out of my way to be arrogant about the nature of cartoons and its true stature. And I’m not talking about rubbish; I’m talking about the best and the best of it in all fields including lots of the things that you cover in The Comics Journal, which are not necessarily my cup of tea, but I realize their skill and their intention.

GROTH: Now, do you think that the best cartoonists rank with the best prose writers?

STEADMAN: Yes, I would say in many cases. I think you’d have to start thinking about the Goyas of this world, the Daumiers, and perhaps the Groszes and Steinbergs and people like that. I think there’s a relevance that’s equally potent. The problem about its durability might have a lot to do with the fact that in many cases it’s untranslatable into other media. It’s not like writing, which is constantly translated into pictorial terms, a film or a play. Written ideas can be often be enough in themselves to be developed into something more ambitious. A drawing may contain a germ of a larger idea, but in-variably it’s overlooked as invalid. Writing is the acceptable form for plot description; only occasionally are cartoons transformed into full productions, like Superman and Batman. Another problem is that whenever comics are turned into films, they look even more ridiculous than they do when they’re comics. And they’re also aimed at children. I think that’s rather important, and, in fact, half the children who go see them are about middle-aged.

GROTH: [Laughter] Yeah. That’s right. There is something about cartooning and comics that is untranslatable into any other medium.

STEADMAN: It might be that it’s self-inflicted, and that’s what I think I’ve been trying to get to. It’s the thing that bugged me, and I think it’s probably just that: we’ve almost made our own pigeonhole, and we’ve somehow refused to come out of it, and we still continue to act like insurance salesmen, and think like them, too.

GROTH: Do you think that might not be a positive aspect of cartooning, because it actually underscores the uniqueness of cartooning?

STEADMAN: Yes, but we’ve got to try to help people understand and accept it as a serious art-form. Unless we make efforts to do that, until we get more arrogant, more self-pride, then we’ll continue to think we’re just dashing off a couple of sketches, that we do this because we can’t really draw, or we can’t really think. It’s very pervasive, that, in the general mind, that’s what we are about. We are a bunch of people who are quite quaint and unique and strange, but we’re only there like the court jesters, to take the butt of everything, to be on the bottom, to be the one who can actually call the king an asshole and get away with it, but really never to go any further than that. Once you get any power, you’re out.

GROTH: Do you think that today’s cartoonists don’t have an accurate sense of their own worth?

STEADMAN: Very much so! I think newspapers have made it that way. They prefer it that way: keep the newspaper cartoonist under wraps. They use them to sell newspapers, but they keep them in a minor role, and they keep them in a supportive role. They don’t give them that kind, if you like, of dignified importance that they might give to their lead political writers. Whether “dignified” is the right word — I don’t think it is, really. They have no status that can be considered a relevance to what people call the real world: they’re the light relief, the space fillers. It suits the newspapers very well to keep it that way because they don’t have to pay so much for them. It’s really time for a cartoon revolution of this kind. It’s the sort I’ve been advocating because I don’t want to belong to the cartoon world which keeps us all in a pigeonhole. People say to me, “Ah, but you’re becoming an artist now.” No, I’m a cartoonist just trying to extend my boundaries to include all things, but now I require a more expressive point of view because it’s another form of cartoon activity. Writing a play can be a form of cartoon activity. If the playwright is using expressive word-forms to make a point, he’s really exaggerating the situation in order to make his point. Well, that’s a cartoon form as far as I’m concerned! It’s a very important area to consider. In fact, I think all basic expressive impulses are cartoon impulses. Any coordination of lines, any configuration of lines, any sort of sudden movement of lines in different directions express something which is limitless. And it’s the same impulses that gets a playwright or a writer out of these very deadeningly rational spots they write themselves in, and there’s something weird! It’s almost like leaping out into the darkness with a crazy thought, just like a cartoonist getting a wild idea, suspending one’s disbelief and allowing the mind to accept the impossible. The same applies to painters who prefer to paint in just what they choose to call the fine art world; they are very often using cartoonist techniques to solve their pictorial problems. Well, that’s plunder, as far as I’m concerned, if we are not going to enjoy any of the benefits of being called “fine” artists, too. What is the opposite of fine, but coarse? So we’re the “coarse” artists? Why do they call themselves “fine” artists? What is so fine about it? Often painting is very earthy and pithy. So it’s hardly “fine,” is it?