Zachary Braun's ongoing science fiction webcomic, Nature of Nature’s Art, has been a staple of my comics reading and constant source of inspiration since I was a teen. I met Zach during my mid-teens on an oekaki board, where he gave birth to the first story arc of NofNA, 10%+, a dramatic, high-octane exploration of what it means to be human, the ethics of assigning or taking away that label, and the hostile conflict that ensues among the main cast as ideologies violently clash. I should mention this story all takes place on an alternate-reality Earth, where the main "human" characters in question are actually sentient, psychic animals. The gravitas these stories contain is hard to accurately describe, but imagine if Charles Stross wrote a science fiction version of Watership Down or if Harlan Ellison wrote a psychologically horrifying take on Redwall. These are poor comparisons but Nature of Nature’s Art goes above and beyond in conveying an intricate, realistic world filled with grounded, complex characters even as they engage is fantastically choreographed fight scenes and engage in psychic warfare over the right to be human, sex, the Singularity, and the self.

Slone Leong: Maybe we can start with talking about your background, personal/secular, and then how you got into art and comics?

Zachary Braun: Sure. That's a good place to start.

I can't think about anything special about my upbringing, although my parents were very lenient with me, and later, my sister. They were both hippies growing up in the '60s. I remember my mother telling me about how she and my father made a conscious decision to never hold any kind of a religion over us, to allow us to decide for ourselves. As social media has expanded and other peoples' stories are being told, it's becoming apparent that this might not be such a common upbringing. There are many childhoods with rigid religious confines or other restrictions that did not have this kind of freedom.

My mother was always into the arts, and was very interested in art history, due to her own father being an artist. There were always art books and art supplies around the house. However, I always seemed to be attracted to comics, the charisma of the characters. The mastery of a character of his or her situation. I was not an outgoing kid, so I could be outgoing by living vicariously through these characters. Expressing myself. When I was in elementary school, I created a bunch of snake characters, because they were easy to draw. There wasn't any real story; it was just a bunch of people whose charisma I could play around with. Things became more and more sophisticated the older I became. It was in high school that I started to create characters with stories in mind, although these stories didn't have strong theses yet, like NofNA stories do today.

Interesting! I feel like that foundation of having ideological freedom shows up in your comics a lot — your characters are in society that always encourages independent perspective and innovation. Also those snake characters sound so cute!

What kind of comics were your favorite growing up, or that impacted you notably? And when did you start taking your stories and craft more seriously?

My favorites growing up... I tended to read a lot of manga growing up, from around the age of 17 on. They stood out to me, because the darkness of western comics didn't appeal to me.

Although there was also this large Batman story I also liked, where Robin was a young woman, and all of the panels were the exact same size. The way the story moved was also very interesting. I remember the Joker dying by laughing to death, cracking his own neck. I can't remember the name of this story, but it was strikingly different from what I was used to from western comics. Watchmen was also interesting in this same way.

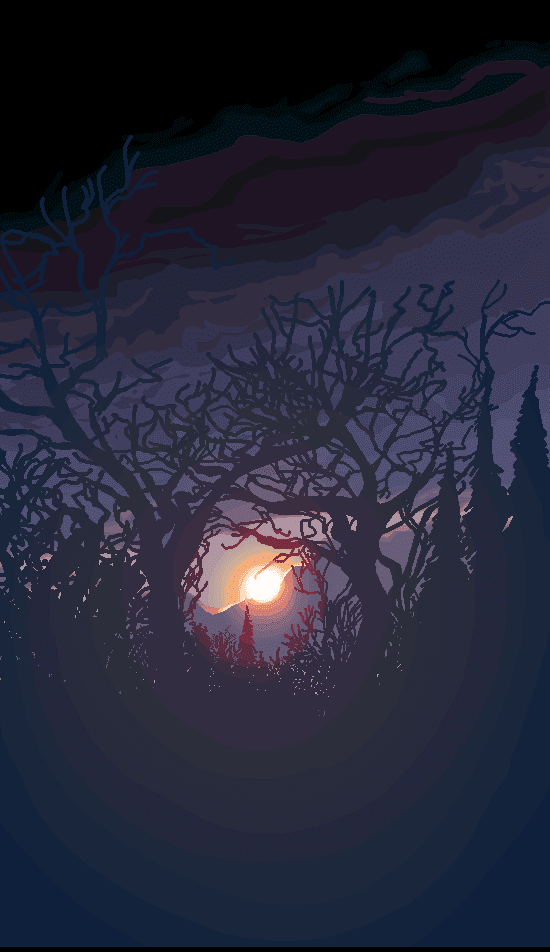

Much later, I discovered Tsutomu Nihei's BLAME!, which was highly atmospheric. I enjoyed that work a lot, because it emphasized this enormous space to the point where it became its own character. From an early age, I was very interested in the juxtaposition between "observing things that are there" and then "those things existing when you aren't there to observe them." The way we make our entire environment a part of ourselves, but, the logical reality of that environment continuing to exist when we aren't there. Meaning, the possession of that environment while we're there to observe it is a delusion; it's its own entity. BLAME! coincided nicely with this.

The above theme of being alone in an environment that isn't really ours is critical to me, even today. This is part of the reason NofNA scenes will have very large backgrounds at points, backgrounds which consume the characters inside of them, standing tall and eternal. They will outlast the characters, and the characters are just temporary players in this play. The meaning of being temporary is part of what makes us struggle against one another, while the eternal backgrounds give us context in a historical way.

This was my main thesis for a long time: things playing out as they were, to their own end. Everything playing out in this temporal theater. This governed the processes behind 10%+, even though the theme for the characters in that story was "attention." It was also the driving force behind Secretary, even though the theme for the characters in that story was "malice." It wasn't until page 16 of Lycosa that I really shifted this philosophy. At that point, I made a full commitment to making the stories more emblematic of themselves. I got rid of the temporal theater and started thinking about how to make the story a portrait of itself.

I feel the same way about BLAME! and I can definitely see that sort of charisma and personality in your environments, especially in Secretary and Solar System. The world the characters inhabit feels like they exist as sentient ‘stone tapes’, dutifully and silently recording the experience of the story.

Making the story a "portrait of itself” is an interesting conceptual goal to me. How have you manifested that in your work?

This concept involved using a lot of metaphor, so that the structure of the story mimicked what was happening inside of the story, or laid meaningful context for the story.

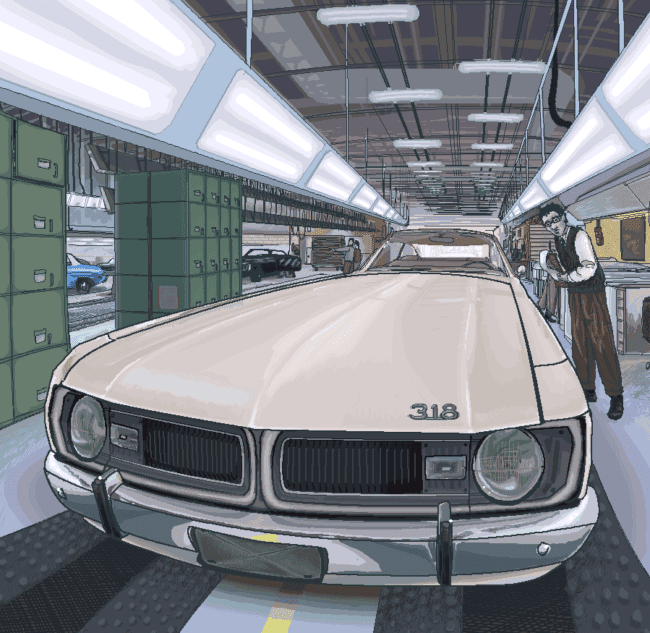

In Lycosa, on that page 16, I had at first chosen random car makes and models to depict all crushed up. I abandoned that idea, because I realized that this was the time to have the page mean something—if not now, then later on, after Lycosa started to ravage the other spiders. Who they were.

My job on that page was to find eight makes and models roughly equivalent to her adversaries, and then have her adversaries perish in the same way that those vehicles did. In this way, the characters become a reflection of the meaning of the story, the junkyards of ourselves.

The employment of that method here might not have been very successful, because it sealed the metaphor behind a specialist subject: cars. Not many people who would read a comic like this know about the intricacies of BMW's identity crisis, or even that the Corvette had a fiberglass body for lighter weight. For later stories, I tried to keep the metaphors more compact, more relevant. I started to use the styles themselves as the metaphor, even the animals' species. If possible, I wanted to have every page mean something to the overall concept of the story, even if that meaning appeared only when thinking back on it.

That’s pretty fascinating, especially not knowing much about cars. Those elements are definitely a deft touch! I think it’s hard to decide when to go more esoteric or more universal and recognizable when creating a narrative's metaphors and symbology. Fun but hard. It would be amazing if you did a director's commentary on your different story arcs at some point.

Now we met in the early '00s, when I was a teen and just starting to explore digital art. Specifically, we met on an oekaki board! What drew you to that little corner of the internet? And at this time, were you pursuing art full time? Did you attend art school at all?

Thank you. I think that it would also be interesting to go over my past stories—the technical construction of them—especially mistakes that I made.

We did meet over on the poor, old, now-defunct oekaki board. When I was growing up, I didn't have anyone else to draw with. Oekaki was a phenomenon which could have only existed at that exact point in time: before social media, but after Java. When I stumbled across that board, I thought, "Hey, this could be fun!" And at that point in my life, I finally had the artistic chops to be able to join. I liked the concept of getting the honor of an archive, which was a challenge.

I was not pursuing art very seriously at the time. I occasionally attended some kind of art class throughout my life, but it was always for fun, or because my parents wanted my skills to be honed. I did not like drawing from life. I wanted to draw things that did not already exist.

Because of this, I had started a few comics before, but they always ended up being abandoned, because I just didn't have a strong sense of purpose. But it was getting later and later into my life and I had to do something. I knew that the older I got, the less energy I would have, and the more financial obligation I would have (and who knows, maybe even medical obligations). I took a brief break from the oekaki board around 2006 to concentrate and finally draw the first NofNA story. It was about two deer who were supposed to be kindred spirits, but one ended up killing the other. It was not executed very well, but it was my very first completed story.

Ah, I would love to read that deer story! And that was the same with me. I was isolated away from any sort of art scene at that time so the oekaki and deviantart were welcoming havens for the things I wanted to draw. I don’t think I ever got an oekaki archive but I definitely loved seeing my friends go all out, practicing and planning in this simple program, trying to achieve something above and beyond.

I don’t know if this is correct, but did you end up becoming a psychologist, or something along those lines? I’m curious as to where you went secularly. You raise interesting philosophical and bioethical ideas in your stories and you have the knowledge of the brain and body to back it up.

Relative to what you said earlier, I would like to bring that deer story back one day and reconstruct in into a modern NofNA story, and show everyone the comparison, which would make all of the mistakes really clear. (P.S. Can't believe you never got an archive.)

I definitely do not have any kind of doctorate (or any degree, for that matter). I was just very interested in how the brain would create all of these psychostructures for itself, and later, how the physiology or neurology would support the psychology. How the physical reality of a glob of interconnected neurons and fat creates the metaphysical. The differences in peoples' opinions, perspectives, senses, all manifest in this one element. It's a big troublemaker. Even identical twins are different, due to the difference in perspective—even if that difference is just the realization of "there's another one of me." And this is our biggest problem! We're a social species, and, we don't have any kind of psychic link. Just empathy, which isn't very accurate with strangers.

Maybe you can talk about your choice of medium for your comics and why you’ve chosen to stick with oekaki. What about the program appeals to you? Why not traditional tools or Photoshop?

The first tool I used to make comics was the Painter software, version 5.5. This is what was used to make that comic with the deer. Painter was good, because it offered a good-looking pencil-sketching tool, and it also had a watercolor tool which worked on its own invisible layer, meaning that you could lay down all of these lines and value with the other tools, and then add more shading and value—and even texture—with the watercolor tool, which was independent from the other values.

Despite this, I started to use oekaki's Paint BBS, not only because I wanted to return to my old stomping grounds, but also because it was much, much faster to simply get an idea out onto the page. Two comic-book-sized pages could be made in a single day. The low resolution was not suitable for printing as it was (that would become another can of worms when NofNA eventually did go to print), but as a comic on a screen, it was perfect for covering a lot of ground in a story in the shortest possible amount of time, while still allowing for color. This emphasis on an application that could work at this speed eventually became NofNA's style, with the low-resolution artwork being integrated into the story.

Occasionally, I would try different mediums, but I would always come back to the perfect mixture of function and speed which Paint BBS offers. I do still use Photoshop for post-processing.

That’s cool you took what worked best for you and your story and made it not only your creative signature but an effective stylistic tool.

Lets talk about 10% which is your first longform webcomic story in the Nature of Nature's Art series and something of a watershed moment for you in your comics career. What was the core seed that began this story? Maybe you can walk me through the process of conception to execution.

10%+ was originally supposed to end with the concept shown on page 17, where the main character's head is on fire after accessing more than 10% of his brain at a time. This story was originally made to clarify the misconception of only being able to use 10% of the entire brain, and I initially imagined NofNA like that: a bunch of vignettes which revolved around different sciences and subjects. But I kept going and going, bringing every plot thread in the story to its logical conclusion. I wanted to try out drawing fight scenes, and there needed to be a good reason for that, and then, the repercussions of such a battle.

10%+ is different from the other NofNA stories in this regard, because I simply had each character play out their interest in this situation to its final scene. I remember the latter section, where the main character was tried, was especially difficult because of this. The readers knew what happened, and every other character didn't, and I had to find a way for them to both figure it out for themselves and get what they wanted in the end. The character Syncope declaring "I can't believe I just proved that" on page 211 was a reflection of my own thoughts. This was before I took notes in a simple text program, and I have a notebook filled with notes on this scene, just keeping track of what everyone knew.

The trial scene is so compelling and intense, I can imagine how difficult it was to orchestrate. Speaking of characters, I find yours particularly captivating (SV and Meander and Quintet are probably my top three favorites, heh). How do you go about developing your characters' voices?

Usually, NofNA is pretty difficult to coordinate, because in each story, there's a theme, and the characters are serving the theme, and everything has to start at these disparate points and then converge at the climax. At least, that's how it should be, ideally.

Character voices are not one of the difficult parts. I just have an idea of how a character would act and run with it. More difficult is realizing what a character would be based on his or her past—how a character would be liable for him- or herself. What shaped the character? How does that psychological profile exist realistically? I spend some crucial time doing character design as I figure out the stories. This isn't the design of the character's appearance—a lot of my characters are very plain and unremarkable—but the psychological design of the character. What ends up making the character act, in accordance with the theme of the story.

One of the things that I strongly dislike about modern character design, is that many characters are engineered to wear their hearts on their sleeve—to be instantly recognizable and evident of their pasts and passions, through both their actions and appearances. This is very good for a commercial product, because it allows your audience to instantly connect with vibrant characters that might represent them. However, it is not representative of real people, and I think that this is a crisis for introducing people to how other people think, especially younger children. People are very deep, and they only become deeper with age, and I don't think a lot of the media we consume reflects that. This might be because we simply don't have the time or money to tell even a single person's whole story, but I feel that we should have media that help to reveal the other sides of people. To teach them that there's probably something more there. This is one of the main reasons I started drawing NofNA: to try and show the depths of human reasoning, and its causes.

I really appreciate that attitude toward character personality and design. I think that’s why I enjoy shoujo so much, the designs are usually simple and not of much note and all focus is on the emotional turmoil the characters go through.

Besides 10%, Secretary is my other top favorite of yours. I find it fascinating that you provided an alternate ending in the PDF version and show different sides of your theses through SV. How was your experience executing this story?

Relative to that trial scene in 10%+, the social interactions in Secretary were much simpler. The difficult part of Secretary was in resolving the main character's thesis, which was very complicated, especially in the way it interacted with other people. Defining "malice" is such a big chunk of the human experience—everything bad that happens to us, that we can perceive as intent. Resolving the technical side of it, how it operated, how he could control it, changed the way I thought about it. And then, how it itself changed, towards the end of the story... and then again, in the alternate ending. This story made me regard "malice," or what a person might regard as malice, as a natural biological process, similar to going to the bathroom. Something that we can't control sometimes, that we just pass haphazardly on to the next person.

In the end, the story had an alternate ending, because some people were disappointed with the original ending, and because I wanted to give those who chose to buy the printed version (which contained the original alternate ending) a good value. A different perspective, just like in the story. I wanted to show how such a small, chance change could bring about a much bigger change later on (the switched tooth). But I'm glad that I got to do both endings, because the scope of "malice" is so broad.

Were you satisfied with the original ending? Or did you enjoy being able to explore the alternate? Malice seems incredibly complex (I'm excited to learn more about it in the Addendum, btw!). Also since we're talking about readers, do you like getting reactions page by page? Is that interaction with your audience, and their theorizing within the their fandom, important to you?

I was satisfied with the original ending, because it was the conclusion of that string of events, that philosophy of malice. It was an animal side of malice. I did very much enjoy exploring the alternative, where the main character did not have his mental faculties stripped away from him, because the other tooth went on to carve a different passage through his brain. This became the more human side of malice, a self-aware side, that could change.

The feedback from readers, like that that I received for both endings of Secretary, is very good just as human communication. When we engage in chat, we don't often get to express complicated ideas, because of the way that chat works. Stories like this are a necessity if you want to offer up a summation of a lot of thoughts that you've been having. It's a point where you can finally communicate with people, and it feels good. Although, there are about 3/4ths of the people reading these stories who do not say anything, simply because they are absorbing it at a piece of entertainment, not as a conversation. And NofNA allows for that. (Readers can even turn off the comments on the main page, if they so choose.)

The reactions from those who do comment are occasionally useful for determining what is effective in the story and what isn't. I've made a few decisions based on readers' comments, like extending a scene for clarity, or making absolutely sure a character's intent is clear in a certain panel in the future.

I find your storytelling quite efficient and clear at conveying your themes yet I feel like you're also very comfortable delving into abstract territory. In regards to your pacing, paneling, and overall layout compositions, you allow a certain amount of indecipherability and this is especially prominent in your fight scenes, where a lot of nonrepresentational visuals are present or figures are depicted in swooshing hatch loose marks. I always find myself especially engaged when these extensive martial arts scenes show up and I feel like your layouts shine the most during them.

How did you develop this sort of visual style for your fight scenes? What do you think about when choreographing those fights and choosing appropriate paneling structures to convey it? What makes you decide to move into abstract territory rather than stay representational?

For action scenes, I just want to convey as much energy as possible. Spilling out of the characters and into the construction of the entire page. If a character is moving quickly, well, we've seen that many times before. In order to not have it be boring, it has to convey all of the energy the character is experiencing at that moment, even at the cost of clarity. After all, when something is moving faster than we can see it in real life, we can't see it.

In animation, there are several ways to convey extremely fast motion or abstract motion sequences, things which we wouldn't normally be able to see. My favorite depiction of these is when the action plays out with all of its energy, acting just as itself, no punches pulled. Then, because of this extremely high energy moment, something happens. It's only when we observe the effects of this happening, the result of this high-energy movement, that we begin to ascertain what has happened. This creates the movement not on the page, or on a screen, but inside the viewer's brain, where it will have the most power.

Not every action is going to be a tour de force of movement. When these high energy movements are rationed appropriately, they can be extremely powerful. Meting these moments out at the appropriate time is very cathartic, and is what drives me through the beginning and middle of the stories.

As to what determines whether it's appropriate or not, it all depends on the story. Inside the story, there's a force called Art, which is the ability of people to connect with one another in a very violent, primitive, immediate fashion. A primal communication, a gateway to another person. The nature of the Art being shown is what determines not only how characters will be depicted to each other, but to the readers as well.

Another aspect that really astounds me in your work is your use of color. What’s your process with coloring and setting up color symbology within the narrative? What goes into deciding when something should be mostly black and white, like Secretary?

For Secretary, the answer is very mundane: this was originally just something simple to work on as I compiled the print version of 10%+, so there was a minimum of color and value, just to keep the work speedy. After I finished 10%+'s books, I then had more time, so I ran with the grayscale theme, and I was able to think about how to use the lack of color. In the end, a completely white background came to represent the main character's sphere of influence, especially his connection with his friend. The presence of value and lack of value was mirrored in the theme of the story, with the lack of value being a world without malice, and the world with value being the real world, where malice exists and was present in the past.

NofNA being what it is, there's a juxtaposition between what's real and what isn't. Characters, strangers interact in reality. I try to keep every panel real, if I can help it, and if I have time for it. When I just don't have the time to make every panel real, I'll use some kind of color theme or pattern that's aligned with the story's theme or the character's emotion.

However, when the animals use Art, they extend their sphere of influence outward, and real colors are superseded by the colors intent in the Art. Occasionally, there will be other meanings for color, such as in Lycosa, where the picture-speech bubbles had their own color language, like green for pain or blue for inquisition, and in Syconium, where the pervasive blue of the labyrinth stands for the adult euphemism of "blue," as well as the electric blue of the "lightning". But the contrast between real color and unreal color will signify the presence of Art—the presence of a person or concept's sphere of influence.

I wanted to touch a little bit on your animation! In Lycosa's story arc, the word bubbles aren't filled with text but tiny drawings and symbols. When you hover over these image-filled bubbles, a caption pops up and often there are amazingly animated grawlixes or punctuation to drive home character's reactions or emphasize dramatic dialogue. What made you depict dialogue this way? And how did you get into animating?

I knew that the dialogue in Lycosa had to be different, because the insect world is so different from the animal world. When I discovered Mr. Erik Bosrup's Overlib Java plugin, which allows for overlays to appear over a webpage, I knew that I could make this possible—keeping the insect world separate from the animal world while also being legible to a human audience.

The animations are an extension of that. Overlib is very flexible, and I was able to place simple and effective animations inside the overlays. The spider world is kind of wacky, and the animations help to drive home how different the speech is. Lycosa, for me, was in part having a lot of expressive fun with these characters whose features can barely emote at all.

Animation in general has always influenced me, because of my interest in conveying energy. When I was younger, I would watch entire animated features using the slow motion feature of my VCR, to see how the animators drew each frame.

So far Solar System is the largest scale story in regards to its setting and one of the most personally moving with its optimistic outlook on humanity’s future. What draws you to science fiction? And what makes you so optimistic about humanity’s future and potential?

To tell you the truth, I'm not optimistic about humanity's future. But Solar System and its conclusion were conducted in spite of this, because it's our responsibility to look up, for as long as we populate this planet. Our main problem as a species is that "look up" means different things to different traditions.

Science fiction is the ultimate escape from this mess. Anything can be possible, even hope. Although, I can't help but wonder if we turn to fantasy to satisfy the impulse to do something, which then quenches that initiative. Too much escape, and nothing will happen in the real world. As a storyteller, my hat is off to those who did get their degrees—via an institution or the street—and are struggling to make a difference.

I think that undeterrable drive in the face of our failures to strive to be better is one of the most heartwarming and encouraging themes in NofNA. It’s self-aware without giving into indifference and cynicism.

Syconium, your current story, circles around the themes of sex, the sublime, idealized bodies, and primal desires. I feel like this story is unique compared to the others NofNA stories, exploring what most people think of as a more... matter-of-fact or “base” side of the human experience, I suppose? Sex is, of course, incredibly crucial to everyone's lives, down to their very identities, but I don’t know if I’ve seen many stories compare those subjects side by side with art and being an artist. Without giving away too much, what inspired this story?

Syconium was inspired in part by the destructive power of sex. It's not an inherently destructive action, what with its principle foundation being a physiological function to create new life. However, we being the social mire that we are, sex has become a commodity, similar to how it persists in the society of the bonobo monkey. Unlike bonobos, we also have a lot of baggage in our social interactions, and this has the potential to make sex onerous. This contrast between the creative power of sex and the destructive power of sex is what I wanted to blaze in the background of Syconium. In the story, I wanted to explore the technical reality of how sex works, and how society has co-opted that to create new meaning for sex.

The other half of my inspiration for the story is I wanted a story in which the main character simply breaks away from this. I wanted her to discover this onus, and then intrepidly traverse it, throwing it off of herself and drawing out her own future, one that she initially wanted. The build-up to this moment is becoming rather long—if it were a printed book, it'd be over 400 pages now—but it's almost there.

On top of all this, I wanted to draw the Chuck Jones Rikki-Tikki-Tavi streak.

Oh no, I’m never going to look at Rikki-Tikki-Tavi the same....

What’s been your favorite theses to explore so far? And what have you learned developing and creating NofNA?

I've learned so much by working on NofNA. Making graphic novels is the most proactive job a person can have while at the same time being the least physically active. There's so much organization and structure to master, so many subjects, and an infinite number of ways to execute it all. I love that this work is so open-ended and requires so much input. What's even more, is the way the subjects change you.

Organizing the subjects for presentation in your story means organizing them for yourself, as well. Secretary, which was my favorite, really changed my outlook on how to approach its dire subject. How important it is to be self-aware, and acknowledging what's at stake. I've even learned things from enthusiastic readers who have left information-filled comments.

Can you elaborate a little more on how Secretary changed your outlook? I definitely go back to that story (and its alternate version) most often and I've formed my own theories around SV's quest to control Malice but it's always great to hear the creator's intent. Also if there's a particular anecdote about your readers' comments that stands out to you, that'd be interested to hear as well!

Secretary forced me to take a good, hard look at what constitutes human aggression, and what can be done to absorb or flow around it. I'd already known that aggression met with like aggression creates an endless cycle of violence, so, I had to wonder about the philosophy required to finally process aggression into oblivion. Just keeping all of these axioms of human interaction in mind—what works, what doesn't—is what trained me to think carefully about my own actions. Before, I was never an aggressive person, but now, I was extra careful. I started to think about what I could do, if I had daily interactions with strangers, in order to stop aggression.

In the story, this aggression is called "malice" because we don't think about other people's motives when we're being inconvenienced by them. We just apprehend animosity. With Secretary, I wanted to hint that there were possibly something more, something hidden, that needed to be thought about. Something that wouldn't occur to you by instinct. A case study of this was shown off in the recently-developed Secretary Addendum, which tells the story of the person who ends up unintentionally helping the main character finish his style.

I don't have any stories about reader comments. One of the best parts of NofNA comments is that everyone is usually willing to discuss things at great lengths in a civil manner.

You've been working on NofNA for 10+ years and sharing it online and also in print through self-publishing. You've also started a Patreon fairly recently. Would you ever be interested in working with a publisher? And what does the future hold for you and NofNA?

I think that I would like to work with a publisher, although I don't know what that would entail. I could certainly lend my newfound expertise in upscaling low-resolution art for the printed page.

For the future, I'm not sure. I have many NofNA stories to tell, but each story takes about two years to tell, on average. I also don't know what my financial situation will be like from now on, or my day-job situation. I've thought about telling the final NofNA story if I felt like I wouldn't be able to work on it in the future. But it's a time of transition for me, and everything is liquid right now.

What are some words of advice for younger artists and cartoonists just starting out? Or people who’ve been sitting on a story idea for a long time but haven’t been able to execute their comic? I really admire your creative drive and your ability to continuously crank out quality work over the years and on a regular schedule! It’s incredibly inspiring.

One of the interesting problems I've had, is, if I have a story to tell, how should I tell it? In the end, I settled on graphic novels, because I loved drawing action scenes, trying to capture the energy of the characters and what's happening. But there's also prose, and now, anyone can make a video game about a story.

Video games are popular, but, they take a much longer time to make, and the element of gameplay can greatly increase the production time of the story. Novels are much more easily accomplished, faster to produce, and more easily accessible by the general public, but the market is somewhat saturated. Despite this, I feel that novels might just edge out graphic novels. The novel allows the reader to use his or her imagination in a way which graphic novels or video games cannot approach. Although, graphic novels are more visually impressive, and video games more impressive still. It's something to think about when aspiring authors have a story to tell.

On advice I'd give on executing that story, I could say something like keep the pace of the readers' reading in mind, which will be much, much faster than the pace of your production. Or, discipline yourself—even when you don't feel like drawing, you need to keep it up until the end. A story is a whole, and all of the parts need to be there in order for it to finally pay off.

But my most important advice is that you aren't going to live forever. I started drawing NofNA because I knew that if I didn't draw it, no one would know the thoughts I was having. The person I was, the communication I wanted to extend to other people, that could only be accomplished by executing my story. I even started the story Solar System earlier than I should have, just because I could feel my time running out. Once you're dead, you won't be able to communicate any longer. Your stories aren't just whimsy you had, they're your will—what you leave behind.