From The Comics Journal #49 (August 1979)

Masters of Comic Book Art

P. R. Garriock Images Graphiques, 1978

Trade paperback: $9.95

The single image is the vital component of the comics medium, just as the single note is the vital component of music, the single frame the vital component of film. Yet, like the note and the frame, without its dozens of peers preceding and following it, the single illustration means nothing in the context of comic art. The essence of the medium is in the succession of images, in the dynamic tension between one frame and the next. If this dynamic tension is not maintained in a series of illustrations, one does not have comics; and if one extracts a single illustration, one has nothing.

Some of comics’ finest artists eventually drop out of the medium to concentrate on single illustration; in fact, two of them — Corben and Windsor-Smith — are represented in the book about to be reviewed. The pundit would probably attribute this migration to greed and laziness — after all, where the comic artist has to knock off scores of illustrations to finish just one job, the illustrator has to produce but one. On a slightly more serious level, one might suspect that the artist is trying to escape the ghetto of “comic art” with its attendant stigma by branching out into a more legitimate field. (There is also the matter of economic pressure — comics are notorious for not paying well.) In addition to this, the artist eventually realizes that the comics medium demands certain sacrifices in terms of complexity and completeness of the individual panel for the sake of legibility and continuity; those whose tendency is toward over-illustration eventually become frustrated with the required simplification and stylization. Whichever of these reasons is dominant, many outstanding comics end up illustrators and, as far as the medium is concerned, it’s a damn shame.

Masters of Comic Book Art was unfortunately compiled by someone who suffers from a similar obsession with the illustrative rather than the narrative. The result is that the book, which seems intended to be a compilation of the finest comics work by the finest comics artists, is in fact a compilation of the finest illustrations by the finest comics artists. The result is not necessarily a poor book in terms of the quality of the individual pieces, many of which are flawlessly reproduced (with, perversely enough, the exception of the only two complete strips reproduced, which are not shot from the original pages but from the comics in which they appeared). However, it fails totally to represent and illuminate the medium we all know and love, namely comics. From the word go, then, Masters of Comic Book Art, with its scores of luscious, full-color paintings and splendid line illustrations by the likes of Moebius, Corben, Wood, and Windsor-Smith, is a failure.

The structure of the book is irritating. It comprises ten chapters and ten portfolios, each devoted to one master of comic book art. This is a reasonable enough balance of material; unfortunately, the chapters are written as a continuous article and do not always end on even pages, so there is a jump line at the end of every chapter. For instance, after the Corben chapter — just before the Corben portfolio — there are three paragraphs on Barry Windsor-Smith, then a jump line cheerfully proclaiming that the text is “continued on page 54.” Magazines and newspapers have excellent reasons for imposing this sort of mental hopscotch on the beleaguered reader, all of them having to do with expediency. Books have no such excuse. It is an irritant that makes one feel unfriendly toward the book from the beginning.

As for the selection of the ten “masters,” I would have felt a little more comfortable if Garriock had not let his obsession with illustrators get out of hand. The ten selected are all worthy — or at least unique and famous enough to make a legitimate stab at worthiness — but with the exception of Will Eisner and Harvey Kurtzman, there are no storytellers — no Adams, no Steranko, no Kirby, and no Kubert. The only reason I don’t cavil at greater length about this dearth of storytellers is that most of them have been talked to death elsewhere and, relative merit aside, an article on Druillet or Moscoso is certainly more apt to yield valuable information to the American comics student than one on Steranko or Adams. Thus, though the selection of artists is skewed, it is a beneficial skewing as far as the public it is intended for is concerned.

Unfortunately, the bias weakens the book severely in terms of the selection of the works presented. What Garriock has done is go to absurd lengths to dig up each artist’s most illustrative work, even though it may be only marginally representative of his oeuvre. Several portfolios are nothing but selections of paintings, and pretty as they are to look at, they’ do not contribute one whit to the study of the comic book work of the artists in question.

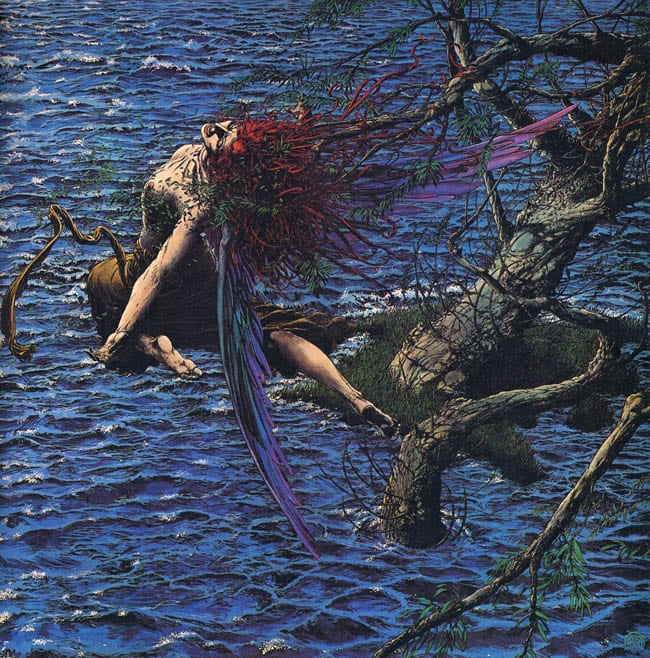

Undoubtedly the worst chapter is the one on Barry Windsor-Smith. Smith rose to fame in the early to mid-’70s not only for his highly illustrative approach to comics and his tremendously effective mood in Conan and a handful of other books, but also for his unique pacing and continuity (involving, in particular, successions of high, thin panels), derived in part from Steranko. The book communicates none of this. Smith’s entire comic book career is encapsulated in two comic book panels (which aren’t even in sequence); then, having done his duty by establishing Smith as an artist who once worked in comics, Garriock proceeds to offer what looks like a catalogue for Gorblimey Press, all posters and prints and paintings. This is absurd; while the latter are undoubtedly better in terms of draftsmanship and polish, they are utterly irrelevant to the comics medium.

Wally Wood’s portfolio is not much better. Garriock does present a whole Mad strip (“Sound Effects”), which is not particularly striking or representative (and printed in teeny-tiny format from the original comic book to boot) and a page from the Pipsqueak Papers, and then it’s posters and prints all over again. What is particularly odd is that the text on Wood contains an elaborate description of one of Wood’s most famous stories, "There Will Come Soft Rains," yet not so much as a single tier of that story is reproduced in the portfolio.

Giraud’s and Corben’s portfolios are much the same: each features two panel progressions (Giraud: a page from Lt. Blueberry and a page from Harzack; Corben: a superb page from Rowlf and a passable one from “Going Home,” probably one of the weakest jobs in terms of technical quality of the separations Corben has ever done) and then gobs of paintings. One of them, the gorgeous cover of Fever Dreams, is printed with the top third lopped off; presumably, this is means to preserve the integrity of the piece by eliminating the logo, price, and such (given Garriock’s predilection for un-comic booky illustrations, I wouldn’t be surprised if that were his reasoning), but it in fact unbalances the illustration, which was specifically designed to include the logo on top. The same trick is pulled with a Kurtzman Mad cover. For that matter, the Kurtzman portfolio is very strange: it contains no EC story material, but a lot of one-page gags, which are by no means Kurtzman’s most significant contribution to the medium; in fact, once one gets past Kurtzman’s remarkable drawing style, they are unpleasantly frenetic and self-conscious. Curiously enough, Little Annie Fannie is not represented. One would think that Garriock, with his thirst for splendiferous color, would have gone for that like a hawk; perhaps Hef was balky about the reprint rights? (In fact, from the dearth of EC material other than Mad, it looks as if Bill Gaines might have sat on his art when queried by the publishers; this would account for some of the book’s problems, but by no means all.)

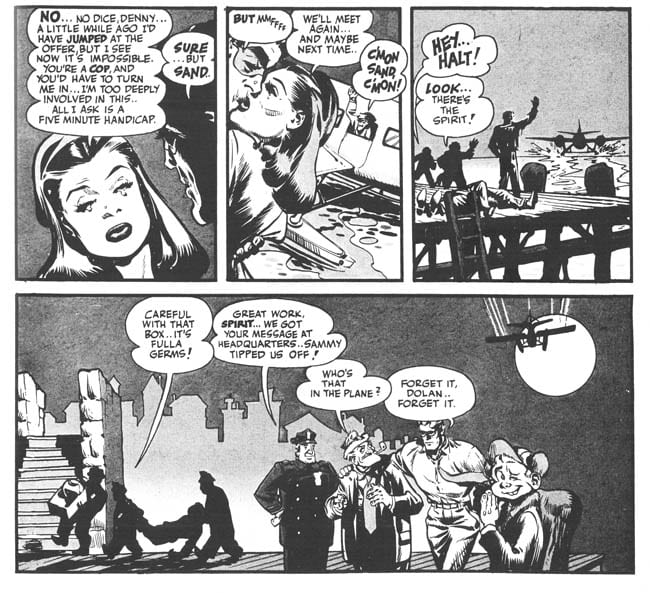

Robert Crumb’s portfolio is a little better, but very hackneyed (it includes “Meatball” — one of the few Crumb pieces I have grown to hate — and the “Truckin” page); the editors obviously shied away from risqué material, consenting only to a picture of a man savagely punching a woman’s abundant buns. With Eisner, whose legacy includes no illustrations to speak of (although I’m surprised none of the Spirit Portfolio showed up), Garriock seems to have capitulated to the inevitable and thrown up his hands in disgust, presenting a seven-page story sans commentary. It’s too bad, because one can get seven Spirit strips every month from Kitchen’s Spirit magazine (and with much better reproduction — this one looks as if it were shot from the Warren reprint). Here, a careful, annotated selection of Eisner’s most memorable continuities and shticks would have been invaluable. But Garriock remains obstinately mum; perhaps he’s sulking because there are no pretty, full-color paintings to gush about.

Coming around the bend, I find only three portfolios satisfactory: Philippe Druillet’s is representative; Victor Moscoso’s, interesting; and Frank Bellamy’s, fascinating. In fact, the chapter on Bellamy alone makes the book worth buying, since the corresponding text is also chock full of information and an invaluable primer to England’s most remarkable comics artist.

The text, as a whole, is readable, a competent introduction to most of the artists included. If you’re familiar with these artists, the text will yield little or no new information; if, on the other hand, you know as little about them as I did about Bellamy, you will find the book a treasure trove.

But Garriock can be sloppy, and much of the book is, presumably because of the scarcity of space devoted to text, written in a hurried style that suggests a master of speech because the guests are eyeing the roast hungrily. (Garriock is not, however, averse to wasting space on such odd diversions as the elaborate plot description of "There Will come Soft Rains" and a pocket summary of the pop-artification of comics, both in the middle of the Wally Wood chapter.) Eisner’s work, for instance, is said to "exemplify the transition from newspaper strips to the more complete narrative of the comic book." How can Eisner’s work exemplify any such thing when he started out as a comic book artist, and, in fact, never worked regularly on a daily newspaper strip? The Spirit is said to have failed to attain universal fame because “Eisner preferred to probe the ironies of justice rather than depict caricatures of righteousness,” viz., Superman. Oh? Perhaps with some elaboration, such statements could stand up; isolated, they’re as worthless as... a single panel from a comic book story. Garriock also pulls a blooper or two, such as claiming that Jules Feiffer and Wally Wood inked a lot of Spirit stories, whereas Wood inked only three and Feiffer was mostly active in writing the strip.

Garriock’s chapter on Druillet is particularly embarrassing. He hurls out adjectives at random ("at once brilliant and chaotic, inventive and obscure"), lapses into horrid clichés ("a symbol of modern man, imprisoned in his individuality..."),’ and even unintelligibility (on Druillet’s working habits: "The text is added [after the picture] within the content of the picture, and the story is then deduced by studying the picture as a whole."). Garriock also seems to be a bit of an auteur-ist, and those artists whose work is very much a collaboration with other people are given most of the credit for their collaborations. There is, for instance, no doubt that Jean-Michel Charlier contributed significantly to Giraud’s Lt. Blueberry, or that Roy Thomas’s vision was an integral part of Barry Smith’s Conan; one would not suspect it from reading this book.

When all is said and done, it must be admitted that the book’s good points make it an excellent buy. The portfolios, unrepresentative as they are, are gorgeous; the chapters on foreign artists (and Moscoso) are valuable and informative, and the bibliographies at the end are outstanding — they can also be read for amusement value, as they include such esoterica as “Lee, S, ‘There’s Money in Comics!,’ Writer’s Digest, Nov. 1947.”

On the back cover of the book is what at first glance looks like a recommendation of the book by Harvey Kurtzman; on closer inspection, it is a recommendation of the artists whose work is included therein (or rather, nine of the ten; Kurtzman expresses coy confusion over who this Kurtzman fellow is). Whether or not it was Kurtzman’s diplomatic way of providing a quotable quote to a severely flawed book without compromising himself, the sentiment behind it is dead on target: buy the book for the artists it features, not for the book itself.