[The following text has been excerpted from Peter Schilling Jr.’s forthcoming book on the duck stories of Carl Barks, published by Uncivilized Books.]

Carl Barks consistently referred to “Lost in the Andes” as his finest work, but I would counter with “The Golden Helmet.” “Helmet,” with its almost zen-like appraisal of a peaceful life, its condemnation of greed and avarice (not to mention lawyers), a story that has humor but not too much, that actually takes itself somewhat seriously, is his finest effort, at the very least in terms of writing (though the art is brilliant as usual). Barks’ claimed that the gags in “Andes” were executed perfectly, the repeating jokes of the gum bubbles and the square eggs, etc., and this is true—but “Helmet,” whose themes run smoothly through this story, is less reliant on knee-slapping gags. “The Golden Helmet” isn’t just a story of adventure, a story of humor, or even bravery (though those traits exist here.) “The Golden Helmet” is Barks’ most somber effort, a story of evil, the evil that lurks in everyone. Even children.

Carl Barks consistently referred to “Lost in the Andes” as his finest work, but I would counter with “The Golden Helmet.” “Helmet,” with its almost zen-like appraisal of a peaceful life, its condemnation of greed and avarice (not to mention lawyers), a story that has humor but not too much, that actually takes itself somewhat seriously, is his finest effort, at the very least in terms of writing (though the art is brilliant as usual). Barks’ claimed that the gags in “Andes” were executed perfectly, the repeating jokes of the gum bubbles and the square eggs, etc., and this is true—but “Helmet,” whose themes run smoothly through this story, is less reliant on knee-slapping gags. “The Golden Helmet” isn’t just a story of adventure, a story of humor, or even bravery (though those traits exist here.) “The Golden Helmet” is Barks’ most somber effort, a story of evil, the evil that lurks in everyone. Even children.

Barks’ visual style in “The Golden Helmet” seems to also suggest that we’re in for a more sobering ride. Gone are the crazy splash panels of “Vacation Time” (or any of the other stories mentioned here, almost all of which have a bent panel or two at least). For the opening scene, as with the rest of this tale, there will be not one skewed panel. Splash panels vanish until twelve pages in, and even then there will be only four of them.

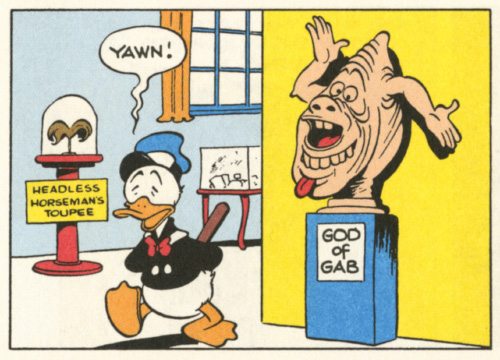

In fact, the opening scene, is one of stasis, boredom. (see Fig. 1) Contrast the narration with the opening of “Lost in the Andes.” Both feature Donald working at a museum: in the latter, Barks wrote, “It is morning of a day destined to live long in history! At the Museum of Natural Science the third assistant janitor is giving orders to the fourth assistant janitor!” This joke just brims with energy. Donald has a huge smile on his face, even as he holds a feather duster.

Here, the narration box simply reads, “Donald is the assistant guard in the Museum at Duckburg!” A guard strikes me as a more intriguing position than janitor, and yet in “The Golden Helmet,” Donald leans against a sculpture of a strange looking “prehistoric cow” (as the placard reads), his eyes are almost closed, and he’s bored beyond belief. Donald’s opening line? “Ho hum!” The Museum doesn’t even have a name—the “Museum at Duckburg?”—and gone is the joke about multiple assistants, even though he’s an assistant guard.

A Viking ship will play a large part in this tale, as Barks foreshadowed his plot points as usual—there’s a big Viking ship in the background, with a large placard describing the thing. Banality wins out: “Old Viking Ship” (there’s no more descriptive term than that?) And this: “This ancient hulk was dug up in Herring, Norway, where it was buried by the Vikings about 920 A.D.” “Hulk” suggests that this ship is merely junk, and the bland sentence communicates simply the most rote facts, and even those aren’t all that interesting.

In this opening page, Donald wanders the museum (as a guard must do), alternating between yawning and bemoaning his fate, a fate of having nothing to do. The museum offers a collection of history’s detritus: the Headless Horseman’s toupee, Lady Godiva’s laundry bag, and, perhaps most telling, a morose statue with a long face, titled “Joy.” At the close of the first page, and over the next few, Donald has circled back to the Viking ship, where he muses over how soft modern man has become. So here the theme asserts itself: the boredom of modern man. The vessels and castoffs of history’s bravest people are trapped in these four walls and behind glass, while we simply wander about, dazed, gazing upon them. At this point, a fat, myopic man with Coke-bottle glasses asks where to find the butterfly collection, leaving Donald shaking his head. And when an effete fellow with large eyelashes says, “Mister Guard, where is the lace and tatting collection?” Donald cannot help but actually climb aboard the “hulk” and pretend, in his words, that he is a “he-man.”

It is while he’s playing this game of the imagination that Donald stumbles across the villain of the piece, Azure Blue, a craggy, goatee’d sourpuss who’s breaking the ship apart looking for a map. Donald shoos him away and then, of course, discovers the map that will transport him from Duckburg to the high seas.

This is quite a find. No mere treasure map, it is, instead, a “log of that old Viking ship!”, as the museum’s curator points out. The curator is a friendly soul, balding, bushy beard, but oddly enough he will never have a name other than “The Curator”. The scene that follows is reminiscent of the opening (though not the prologue) of Raiders of the Lost Ark: in The Curator’s office, we learn that the map reveals that the ship was helmed by one Olaf the Blue, and that in the year 901 landed on the coast of North America, “years before Eric the Red!” (The man who truly “discovered” America.) To prove that he landed on the shore of North America, Olaf buried the eponymous helmet, and the map points to exactly where this thing is located. Excited that the Duckburg Museum has proof of exactly who discovered America, the Curator spins Donald around, happily shouting, “You’ll be famous! The museum will be famous!”

Ready to dispatch an expedition to retrieve the prize, the Curator is suddenly interrupted by Azure Blue and his lawyer, Sharky, who spouts a weird Latinate legalbabble. They demand the map, claiming that Blue is the descendant of the original Olaf, and that by owning said helmet Azure will, in fact, become the King of North America.

Barks concocted a wonderful historical mini-backstory, suggesting that during the time of Charlemagne the rulers of the world agreed that whomever discovers a new land shall own it, unless he claims it for his king. Olaf claimed it for himself, so now it goes to his distant relative, Azure Blue. “How can you prove he is Olaf’s nearest of kin?” The Curator shouts, to which Sharky replies, “Flickus, Flackus, Fumdeedledum!”, and then: “Which is legal language for, ‘How can you prove that he isn’t?’” And with that, they grab the map, and head out the door to retrieve the Golden Helmet.

What’s interesting is that this is essentially an adventure of attitudes. Whereas, say, in Raiders, Indy is out for adventure, but he’s also going to help stop a menace that is physical—the Nazis will use the Ark of the Covenant to literally destroy other, freedom-loving armies. With the Ark, they could (had their faces not been melted off and heads exploded) ruled the world against everyone’s will. Here, this is a threat of perception: if Azure Blue gets the helmet, he will own North America, but his control over the continent depends solely on whether the population as a whole actually believes him to be so. It depends on armies of lawyers and politicians, each one, we imagine, angling for whatever advantage they can get from Blue. Such is the power of this “law” that it will even dissolve boundaries—notice that the owner of the Golden Helmet is not king of America or Canada, but North America.

This is what modern man has come to: if someone says they’re the king of North America, we won’t fight, but merely hope that politicians and lawyers can get us out of this mess.

Even before we can get this story rolling, we need to see the worst of people, this time in the kids. Donald races home to find his nephews stupidly shooting marbles in the living room, bored, eyes half closed, making one wonder if kids back then were as challenged to get out and about as they are today. So ignorant of geography that one of them asks if Labrador is a coat, Donald runs headlong into a wall out of exasperation. But soon they’re on their way, taking an all-night flight to Labrador (with a nifty fold out queen-sized bed in it—man, travel was awesome back then).

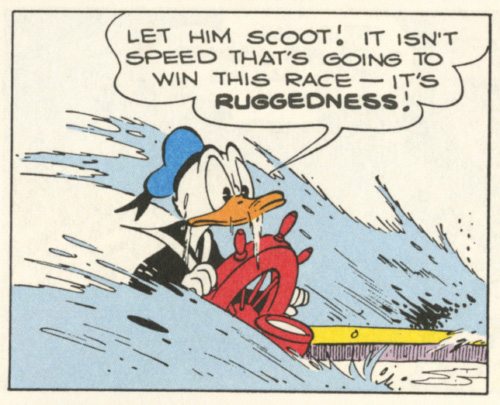

The chase is on. And we notice that the sea excited Barks more than any other landscape. Inspired by the richly detailed newspaper comic strip Prince Valiant, Barks played not only with the breathtaking visuals of a turbulent sea, but also with a rocky coastline that is as inhospitable as Mars. This is a bleak, unforgiving world that encompasses this chase, and Blue is ready for it, with his yacht, filled with reporters (to verify his finding the helmet), and a warship (strangely numbered ‘313,’ same as Donald’s jalopy) for protection. On the other hand, Donald will give chase in a smaller boat, tossed about by the waves. “It isn’t speed that’s going to win this race—it’s ruggedness!” he says, as a cold spray blasts him at the wheel of his boat. (see Fig. 2)

Again, Barks revealed Donald’s impressive skills through action: he’s adept with a sextant and compass, knowing exactly where he’s going with both. Like the fire scenes in “Vacation Time,” he presses forwards, even as scores of puffins sail by in the opposite direction, away from an impending storm. Eventually, things get so rough even the destroyer turns around, and Azure’s ship is crashed upon an iceberg.

We know this because Donald spies the crew of Blue’s ship, and its passengers, in lifeboats heading back south. And he is not the least bit interested in seeing if he can help, or even radioing for help, and in fact the boys dance a little jig, celebrating their victory. The race for this helmet has already stripped our heroes of their humanity.

Of course, it cannot be this simple, as the luck of Azure Blue demands that, in a thick fog, he accidentally encounters the ducks and steals their boat, leaving them to survive in a life raft themselves. But they’re equally fortunate: discovering the wreckage of Azure’s boat, which includes a sail, they’re able to jerry-rig a mast and shoot across the sea and up the coast just like Vikings, and in hot pursuit.

Azure reaches the coast first, the location of the helmet, and yet cannot find it, thus prompting Sharky, his lawyer to sneer that Azure should “sue somebody—anybody.” This particular comic was written in late 1951 or early 1952, during or just after the time when Barks was involved in an awful divorce from his alcoholic second wife. Lawyers no doubt left a bitter taste in his mouth, and thus Sharky provides a constantly negative (and at times tiresome) dialogue, suggesting, again and again, that Azure can sue for every setback life sends him. (see Fig. 3)

But Sharky’s important, at least in the way that this odd story is constructed: Azure can only make his claim through the power of law, which Barks seemed to believe was eminently pliable, provided you had a good lawyer. Without Sharky, this adventure loses its power, a power that becomes seriously warped as the story progresses.

Donald is able to withstand the worst the sea has to offer, and though the kids endure this as well, they do so with a lot of complaining. Up and down the headland they go, vainly seeking the cross-marked spot, to no avail. Finally, Azure and Sharky literally crash into Donald and the boys yet again, this time ramming their boat and sinking them

offshore.

But this helps our heroes. Washed ashore, one of the kids realizes that the cross-shaped headland would in fact erode over time—and it turns out they’re standing right by the mound that contains the Golden Helmet. (And ensconced beneath a puffin’s nest—when Donald goes to retrieve it, he gets a “golden helmet” of smashed eggs on his head. Again, eggs!)

Looking through binoculars, Blue sees that Donald has the helmet, and in the one mediocre plot twist, steals it back from Donald by… sneaking up and taking it from him. After Blue sneers and proclaims victory, as they march toward his boat (where the Ducks are to become his slaves), the Curator drops a stone on Blue’s head, and takes the Helmet yet again. With the evil prize safely in his possession, the Curator demands they board the ship and sail into deep waters, where he can toss the thing into the ocean.

And now comes the dark heart of “The Golden Helmet.” As they sail deeper and deeper into the Atlantic, which becomes as bleak and depressing as the desert in “The Magic Hourglass,” the backgrounds become sparse, languid. The seas have waves, but the ship moves in a straight, flat line across each panel. Gone is adventure, gone is the turbulence (and beauty) of the Atlantic, and what remains is pure avarice.

For the Curator, on Sharky’s advice, decides to keep the Golden Helmet. Since Sharky has proven that anyone can be Olaf the Blue’s kin, the Curator has as much right to be the owner of North America as Azure Blue, or anyone else for that matter. “Everybody will have to go to a museum twice a day!” he proclaims, and then proceeds to list off all the museum-friendly things that will occupy the lives of North Americans under his rule.

But the Curator is exhausted. He collapses, and Donald grabs the Helmet. Midway to tossing it into the sea, Donald suddenly has a vivid image of himself, clad in ermine, sitting atop a gold throne that reads KING of North America. Sharky leans in, whispering, and tells our man that a good lawyer can finagle the legal angle.

Donald’s full of life now, shouting, “I won’t take a thing away from them!” as the Helmet, which he’s wearing, comes down over his eyes. When Sharky inquires about what Donald expects to possess, he sneers that he’s going to force people to wear meters on their chests and pay him for the very air we breathe. (see Fig. 4)

Leave it to Donald to take this to its farthest point, even growing paranoid and depositing everyone—including his nephews—on an iceberg when he thinks they’re trying to steal back the Helmet. But one of the kids sneaks the compass from Donald, leaving him, on a cloudy day, unable to read the stars to determine where he’s sailing.

After a polar bear lands on Donald’s ship, devouring all their supplies (Sharky has joined him, of course), the Helmet and its power do little to feed either of them (much like the conclusion of “The Magic Hourglass”). Suddenly, through the fog we see a Viking ship—Huey, Dewey and Louie took an axe and shaped the iceberg like the old hulk in the museum (and well done, boys).

Donald is so happy to see his nephews that he renounces ownership, which of course makes Sharky grab the Helmet and proclaim himself owner, but by now everyone’s tired of the joke (and besides Donald was the best, evilest owner, anyway.) One of the boys grabs a fish and hurls it in Sharky’s face. The Golden Helmet flies from his hand and down, down into the depths, never to be seen again.

So we come around full circle. Donald’s had his adventure, even had a close up look at the worst instincts in his own breast, and is back to work at the museum. The laywer is back to his job, we presume, the Curator back curating. “That rugged life had its points—but I don’t know—“ Donald says, staring again at the Viking ship. His ruminations are interrupted by another effete gentlemen, with giant eyelashes and weird pursed lips, who asks where to find the

embroidered lampshades. As Donald begins to give directions, he gives up, choosing instead to take the man there. “Darned if I ain’t interested in embroidered lampshades, myself!”

What is the message here? Was it simply to tell people not to question their peaceful lives? The opening scenes of “The Golden Helmet” suggest a world of total banality, of boredom. But by its end the notion that the adventurous life is worth living—even if it’s not financially rewarding—has vanished, with the final panels, suggesting that this life, this comfortable life in America, is worth living, dull though it may be. Barks was no doubt sick of lawyers, but perhaps “The Golden Helmet” is a note to himself, a suggestion to give up any dreams of wealth, to celebrate simply working as a Disney artist with its meager pay. Is this Zen-like resignation to the nature of our prosperous banality, or Barks giving up on life? I don’t know, but I do love the bitter aftertaste of “The Golden Helmet,” which remains, to me, a startling concoction even by Barks’ often dark standards.

Peter Schilling Jr. is the author of The End of Baseball, and writes about film and the arts for a variety of publications. He has been reading and studying Carl Barks’ entire catalogue since he was a child.