Cathy, Cathy Guisewite’s eponymous chronicle of one woman’s struggles with the “four guilt groups: food, love, family, and work,” ends not with a bang, but a simper. She visits her mom, claiming to have news. Mom shores up the strip's feminist bonafides: “You’re an incredible woman from an incredible time for women! You have to know anything’s possible!” She is visibly anxious. She is preparing for the worst. But there is no need to worry: Cathy, hand on belly, is pregnant. The fetus emits a single, pink “Aack” from within the womb. At last, she has it all.

Cathy, Cathy Guisewite’s eponymous chronicle of one woman’s struggles with the “four guilt groups: food, love, family, and work,” ends not with a bang, but a simper. She visits her mom, claiming to have news. Mom shores up the strip's feminist bonafides: “You’re an incredible woman from an incredible time for women! You have to know anything’s possible!” She is visibly anxious. She is preparing for the worst. But there is no need to worry: Cathy, hand on belly, is pregnant. The fetus emits a single, pink “Aack” from within the womb. At last, she has it all.

Despite this attempt to encompass both domestic bliss and feminist ambition, Cathy’s 2010 end seemed to please no one. In a piece for The New Yorker entitled “The Demise of Cathy,” Meredith Blake lamented that, like Family Circus, Cathy is “hopelessly out of fashion.” “Perhaps Cathy spoke to the women of the seventies and eighties,” she allowed, “but nowadays the strip feels, well, cartoonish. The facile jokes about feminine neuroses are the essence of everything that people have come to dislike about chick lit.” Over at The Frisky, Jessica Wakeman was markedly more positive, deeming the strip “groundbreaking” and remarkable for validating the lives of single women. But still, she protested: “I’m not saying the “Cathy” strip was particularly feminist, because it wasn’t: the character was obsessed with finding a husband and watching her weight.” It is “kinda outdated… and certainly it’s still stereotypical and annoying.” The Los Angeles Times criticized Cathy for “starting to feel a bit old,” and compared it unfavorably to Sex and the City, Melissa Banks’s The Girl’s Guide to Hunting and Fishing, and Jennifer Weiner’s Good in Bed. Feministing.com was more measured, recalling that “from what I heard, during her inception in the 1970s, she was actually a breath of fresh air.” But still, the boom was lowered: “I don’t know what happened. It seems that Cathy went from Everywoman to a giddy, whiny, chocolate-eating woman that seems to have no sense of self.” Even the Jezebel community mustered little fondness: The top comment beneath “Cathy’s Last Act Ack” excoriates Guisewite for undermining the strip’s message with a comfortably patriarchal ending.

Beneath this intellectual crust, however, lies the bubbling magma of Cathy-anger. The Observer chronicled the GoComics.com commenters who cheered the end of such a “neurotic wimp,” the Democratic Underground forum threads “for all those who hate the comic strip Cathy,” the blogs that replaced Cathy’s captions and word balloons with expletives and fat jokes. The roundup remarked, with a blinkered sort of innocence, “people really hate this comic!” Look up #WaysCathyShouldEnd on Twitter, and you’ll find a snapshot of 2010 vitriol: “Hoarding experts arrive too late to find Cathy flattened under a heap of diet aids, cats and dating books,” “In a fit of self-loathing, Cathy performs at-home liposuction with a carving knife and a dustbuster; dies of sepsis,” and, perhaps most emblematically of all, “just like Sylvia Plath did.”

No one mourned for Cathy. Her strip collections have not become perennial movers, as with Calvin & Hobbes, Zits, Big Nate, The Far Side, or even Garfield. She has not taken her place among the great works of feminist fiction, or even the sort-of-okay ones. She isn’t fondly remembered by those doyennes of today’s “relatable” comics, who operate most squarely from within her shadow. She is too pitiful for feminism, too female for the mainstream. She is, plainly, lame.

But Marmaduke is also lame. Beetle Bailey is lame. Family Circus, as previously mentioned, is profoundly lame. Yet none of these strips invite the fury that Cathy does. Sure, you get an Eldritch Family Circus here, a Garfield Minus Garfield there—some of which merely enjoy the juxtaposition of the depraved against the wholesome, some of which have more nakedly critical points in mind. They do not, however, inspire the kind of hatred The Observer was so struck by. They do not spur a wailing and gnashing of teeth over just how massively they have failed their audience. They do not end up on Saturday Night Live, played by Andy Samberg, reduced to jokes about how unfuckable and lonely they are.

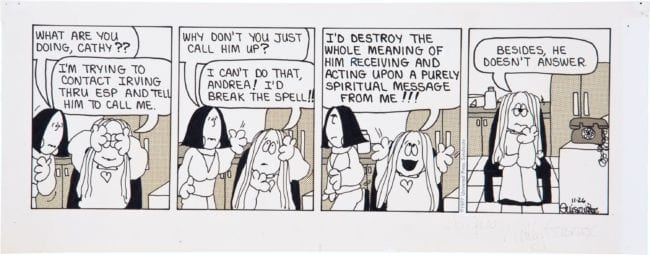

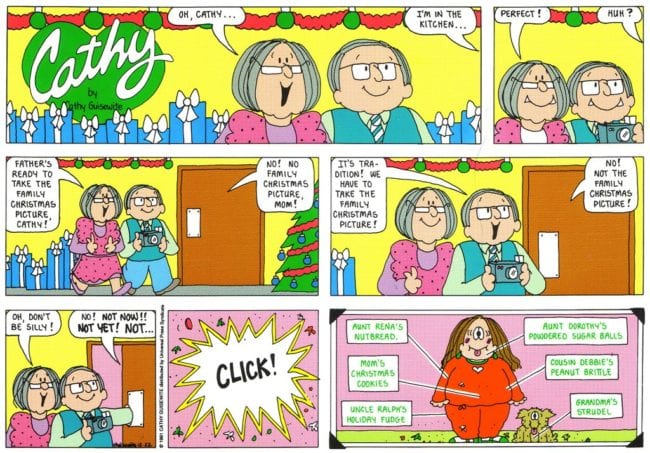

It is not enough, really, to say that Cathy is lame. Cathy is not lame the way your math teacher’s car is lame, or the way a megabrand on Twitter calling something “on fleek” is lame, or the way a middle schooler threatening to murder you over Overwatch voice chat is lame. No: Cathy embodies all of that disparate lameness—all that mundanity, all that impotence, all that visible effort—and makes it female, which is the lamest thing of all. Cathy is sad, but not in a way that is elegant. Cathy is angry, but not in a way that is sexy. Cathy hates her thighs, but loves chocolate, and so she is at fault. Cathy laments her boyfriend’s inadequacies, then rushes to fulfill his whims anyway. Cathy strives to be a good employee while excoriating the drama and pettiness of her office. Cathy is one long, decades-spanning whine; a caterwaul instead of a clarion cry. She is not beautiful, nor, by the end of the strip in 2010, even particularly young. Cathy is your mom, and your mom’s lameness, in its symbolism of all that you struggle to leave behind, is the most dreadful normie lameness of all. Her abjectness, then, cannot be embraced. It can only be refused.

It is not enough, really, to say that Cathy is lame. Cathy is not lame the way your math teacher’s car is lame, or the way a megabrand on Twitter calling something “on fleek” is lame, or the way a middle schooler threatening to murder you over Overwatch voice chat is lame. No: Cathy embodies all of that disparate lameness—all that mundanity, all that impotence, all that visible effort—and makes it female, which is the lamest thing of all. Cathy is sad, but not in a way that is elegant. Cathy is angry, but not in a way that is sexy. Cathy hates her thighs, but loves chocolate, and so she is at fault. Cathy laments her boyfriend’s inadequacies, then rushes to fulfill his whims anyway. Cathy strives to be a good employee while excoriating the drama and pettiness of her office. Cathy is one long, decades-spanning whine; a caterwaul instead of a clarion cry. She is not beautiful, nor, by the end of the strip in 2010, even particularly young. Cathy is your mom, and your mom’s lameness, in its symbolism of all that you struggle to leave behind, is the most dreadful normie lameness of all. Her abjectness, then, cannot be embraced. It can only be refused.

So really, the Cathy-hate makes sense. To the everyman, it’s a dumb chick thing. Everyman thinks Elena Ferrante and Octavia Butler and Stephenie Meyer all create basically the same work, so fuck ‘em. And even to the educated everyman, who prefers Updike to Cussler, Cathy is—well, if not something he’d outright deride as a “chick thing,” something he finds somehow ineffably worthless. He doesn’t have a problem with women’s art really, it’s just, he’s never really loved anything a woman has made and if you get a few glasses of scotch into him, he’s a got a rant ready on how feminism has sterilized the lusty truth of man’s genius.

Womanhood is mundane, is what it comes down to, and Cathy operates squarely within what we understand “womanhood” to be. Women’s work is diapers, typing, cooking, and data entry—Cathy dwarfed by stacks of anonymous paperwork, celebrated for her diligence but never innovation. Woman’s play is frivolous, superficial, distracting, and materialistic—Cathy enjoying a chick flick, a cute stiletto, an evening in with a friend and some ice cream. Women’s sorrow is only poetic if it can become a symbol that means something to a man—Cathy cries most regularly over her inability to become that symbol. Her frustrations at work, including an episode of sexual harassment from her boss, could never be considered powerful in the manner of The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit or Death of a Salesman. Her play is goofy—and the strip itself is, of course, an artifact of women’s play. Her sorrow is to be mocked. “Ack!” Samberg screeches, as the twitterverse cackles on about sepsis and lipo. So, no, she will never be lofted into the ranks of the comic strip heavens. No one remarks, going on a decade since the strip’s end, about the expressiveness of Guisewite’s line. No one discusses the artfulness of the interplay between Cathy, largely ambivalent to Feminism-with-a-capital-F and her more openly political friend, Andrea. The consciousness of this choice—as Guisewite once remarked, embodying the position of women “launched into adulthood with a foot in both worlds”—will not be lauded. Attempts to praise such things are met with a wrinkle of the nose, and a suggestion that comparing Cathy to say, Calvin & Hobbes or Terry and The Pirates is absurd, regardless of whatever point is made. I know this rebuttal well because it sounds in my head even as I write this paragraph. I mean, okay, it sneers, but it’s Cathy. This voice is silent as I impress male colleagues with my ability to find things to praise in the thong-fest that is 1990s Wonder Woman. It is silent as I argue for the need to appreciate the artistic lineage of the absolute dregs of early-2000s gamer-dudes-on-couches webcomics. It is silent as I appraise the strengths of Hogarth’s A Harlot’s Progress, a work of sequential art that openly loathes me. But it sure has a lot to say when I apply the same approach to something as mommish and embarrassing as a quantifiably groundbreaking chronicle of late-20th-century female anxiety.

So yeah. Guys, and the little guys that live within the hearts and minds of women, hate Cathy. Duh. But what of the feminists? Why is there no defense from them? How has Cathy managed to fail them so utterly?

So yeah. Guys, and the little guys that live within the hearts and minds of women, hate Cathy. Duh. But what of the feminists? Why is there no defense from them? How has Cathy managed to fail them so utterly?

She is, as they state, not a role model. And though the need for female role models is real, so too is the use of this argument towards patriarchal aims. I’m not the first to suggest this; criticism of the Strong Female Character has become widespread in the last few years. Everyone’s seen and laughed at Kate Beaton’s satire of them. But it stands to be stated again, plainly: though women need figures to aspire to, so too do they need figures to empathize with, especially created by women. We need art to help us reckon with being neurotic, angry, and helpless as much as we need art that inspires. Because we are human, not hothouse flowers.

But beyond this, there is a certain reproach in the tones of Cathy’s female critics. A frustration: why couldn’t you do better? How could you fail so visibly? It is an anger at her imperfection that reveals an implicit understanding that Cathy’s circumstances are not fair, that her stumbling weighs more than a man’s. It is a criticism born from fear of censure—what might Cathy’s weakness bring upon us? What happens if we cannot be the Angel in the House, the Woman Who Has It All, the valedictorian with a great ass and a scholarship to MIT? What if we are people—fallible, cellulite-ridden, and frustrated as any man has ever been?

In Backlash, her landmark study of the post-Second-Wave era, Susan Faludi pays particular attention to the patriarchal reversals of the 1980s. Over and over again, she finds the establishments of media, psychiatry, entertainment, and politics identifying misogyny and placing the blame for it on women. You’re right, cosmetic companies learned to soothe, the world is unfair to you as a woman. Good thing you can empower yourself with your right to well-lined lips! Gosh, mental health professionals chirped, violence against women had really spiked—it must be because of Women Who Love Too Much. Unhappiness, violence, low wages: all of it was real! And all of it was women’s fault!

Over and over again, Faludi highlights the success of this approach. It’s one-two punch is unbeatable: the illusion of empowerment followed by the same old call for feminine self-improvement. All the consciousness-raising in the world couldn’t blot out the little voice that sounds in a woman’s ear from birth, telling her that her problems are actually her fault, and that if she just tried harder, she’d get everything she wanted. Sure, Andrea Dworkin had a point or two, but wasn’t it also just as likely that maybe she was a dumb fat bitch who needed to get laid? Wasn’t it tempting to be beautiful again, to enjoy a man’s smile, to expect nothing from him and escape disappointment? Misogyny, it turned out, was women’s fault—one more burden to carry, one more thing to swallow, one more revolution averted.

The Backlash era is Cathy’s era. There are comments, here and there, scattered across forums and message boards, from women who remember its debut in 1976. How fresh! How funny! But they are drowned out by the feminists of my era, who feel most intimately how irritating Cathy is and how entirely that is her own fault. She is weak. She is whiny. She is what we are terrified of becoming. I get it; I spent years of my life pretending to prefer Transmetropolitan to Peach Girl. Being a woman is okay when it means jiggling d-cups but not so much when it means enjoying things that might alienate men. Cathy was, and is, a liability. She reveals us as victimized. She reveals us as creatures that do not exist for men. She reveals our effort. Sometimes we are sad, because we ate with a heedlessness we are not allowed. Sometimes we are angry, because our bosses keep cornering us after hours. Sometimes we are anxious, because what we saw in the dressing room mirror made us cry, and the fact of our sadness—our horrible, mortifying, pitifully female sadness—is as sad as the feeling itself. We are Cathy and Cathy is human and there is nothing less ladylike to be.

And so we must repudiate her. There has always been a problem of continuity in feminism, a tendency, stoked by the patriarchy we swim in, to slash and burn our past. How often do I hear people who describe themselves as feminists recall bra-burning that never happened, positively or negatively? How often do we reinvent the wheel, because whoever did it the first time has faded into some boring old lady who we must not become, who we surely will avoid becoming if we just ignore her as hard as we can? Cathy, whatever her origins, has become that woman. And beyond everything I have just argued, it comes down to that. Cathy is old, and old women are expendable, and even we feminists are in a hurry to be rid of them.

And so we must repudiate her. There has always been a problem of continuity in feminism, a tendency, stoked by the patriarchy we swim in, to slash and burn our past. How often do I hear people who describe themselves as feminists recall bra-burning that never happened, positively or negatively? How often do we reinvent the wheel, because whoever did it the first time has faded into some boring old lady who we must not become, who we surely will avoid becoming if we just ignore her as hard as we can? Cathy, whatever her origins, has become that woman. And beyond everything I have just argued, it comes down to that. Cathy is old, and old women are expendable, and even we feminists are in a hurry to be rid of them.

So I have a proposal: fuck that. Cathy is important. And beyond all of that? Cathy is good. Yeah. Cathy is incisive and funny and clever. Cathy takes the slop of my life, the shame and the pain and the work of it, and manages to find it funny without diminishing it. All those women who taped up Cathy comics to their refrigerators and cubicle walls? Their appreciation is just as meaningful, multidimensional, and significant as your love for Calvin & Hobbes, Pogo, and Life in Hell. Cathy managed to make women laugh about the circumstances of their lives without blaming them for those circumstances. Cathy doesn’t make you feel like a shitty feminist for hating your thighs, Cathy just wants you to know that you’re not alone in feeling that way . Cathy bridged the divide between the second and the third wave, the origin of modern feminism and the backlash against it, the baby boomer and all who came after with gentleness and panache. And if you’re not personally into it? If Cathy still doesn’t make you laugh, make you sigh, make you sit down and appreciate its charms? That’s fine. You don’t have to like it. But you can respect it the way you respect the myriad of work by men you do not personally enjoy but understand mattered.

“I am not stopping the strip because I think anything has been resolved,” Guisewite remarked in 2010. “When I see my daughter and her generation, I see that a lot of the games between men and women, the fixation on fashion—‘I’ll die if my hair doesn’t look right.’ And I really thought we could have lost that in the last 30 years. But I guess we haven’t.” She’s right. We haven’t gotten there yet. In a lot of ways, we’ve slid further from where we’re trying to get to, where we might be able to be human at last: fucked up and failing sometimes, but still worthwhile. Until we get to that point, I’ll keep reading Cathy. I’ll keep hoping that someday, it won’t ring so true. I’ll keep laughing as I recognize my own struggles, my own frustrations, and my own joys. And for a while, I won’t be alone.

“I am not stopping the strip because I think anything has been resolved,” Guisewite remarked in 2010. “When I see my daughter and her generation, I see that a lot of the games between men and women, the fixation on fashion—‘I’ll die if my hair doesn’t look right.’ And I really thought we could have lost that in the last 30 years. But I guess we haven’t.” She’s right. We haven’t gotten there yet. In a lot of ways, we’ve slid further from where we’re trying to get to, where we might be able to be human at last: fucked up and failing sometimes, but still worthwhile. Until we get to that point, I’ll keep reading Cathy. I’ll keep hoping that someday, it won’t ring so true. I’ll keep laughing as I recognize my own struggles, my own frustrations, and my own joys. And for a while, I won’t be alone.