You probably do not know Charles Johnson for his cartoons. These days, Johnson is primarily heralded as an academic, novelist, short story author, and screenwriter. His fictionalized slave narrative, Middle Passage (1990), earned him a National Book Award, and his Being and Race: Black Writing since 1970 (1988) was an important early tome in Black Studies—both of which no doubt contributed to Washington University in St. Louis acquiring six decades of his papers in 2021. Another underappreciated figure in the tradition of Black comic artists, Johnson worked as a cartoonist, primarily during his high school, college, and grad school years. He had an outsized presence in the Black press of the 1960s and ‘70s (Ebony, Jet, and Black World), although he was never syndicated; and, as he often points out, he also published in mainstream venues like the Chicago Tribune.

If in 1939, E. Simms Campbell, the artist of Cuties, became the first nationally syndicated American Black cartoonist, it did not necessarily lead to a sea change in the wider cartooning field.1 Graphic representations of Black people in the 1930s-1940s remained dominated by racist tropes based in blackface minstrelsy via characters like the Young Allies’ Whitewash Jones (a friend of Captain America’s sidekick Bucky Barnes) and the Spirit’s sidekick Ebony White - both of whom, as their names imply, left much to be desired. As scholars Frances Gateward & John Jennings point out, however, Black artists were increasingly representing themselves, in the Black presses of the 1930s-1950s (like the Pittsburgh Courier) or in comic book anthologies like Orrin C. Evans’s one-off All-Negro Comics (1947).2 Jackie Ormes’s Patty-Jo 'n' Ginger (1945-1956) was so successful it spawned a pioneering hard plastic toy doll. By the 1960s, the civil rights movement had begun to reverberate in newspaper comics, with the debut of Morrie Turner’s strip Wee Pals (1965-2014) and Brumsic Brandon Jr.'s Luther (1969-1986). Brandon’s daughter, Barbara Brandon-Croft, would later create the strip Where I’m Coming From (1989-2005), making them the only father-daughter pair to both achieve national syndication.3

While the work of Brandon and Brandon-Croft has been collected and published over the years, Johnson has not had the same treatment. Many of his cartoon works would be doomed to obsolescence, especially one-off books like Half-Past Nation Time (Aware Press, 1972), published by a soon-to-be-defunct Californian outfit, if it were not for the new collection All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End (New York Review Comics, 2022) which tracks his life as a comics artist, especially from 1965-1975. This volume not only resuscitates albums like Black Humor (Johnson Pub. Co., 1970) or the unpublished Lumps in the Melting Pot (1973), but reconstitutes the humor of a specific historical moment: the height of second generation of civil rights activists, in the Black Panthers Party (1966-1982). The volume is an important cultural and political corrective to a 20th-century American tradition of political cartoons that long trafficked in racial stereotypes and stoked fear about immigrants, non-white populations, and Black radicalism.

While the work of Brandon and Brandon-Croft has been collected and published over the years, Johnson has not had the same treatment. Many of his cartoon works would be doomed to obsolescence, especially one-off books like Half-Past Nation Time (Aware Press, 1972), published by a soon-to-be-defunct Californian outfit, if it were not for the new collection All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End (New York Review Comics, 2022) which tracks his life as a comics artist, especially from 1965-1975. This volume not only resuscitates albums like Black Humor (Johnson Pub. Co., 1970) or the unpublished Lumps in the Melting Pot (1973), but reconstitutes the humor of a specific historical moment: the height of second generation of civil rights activists, in the Black Panthers Party (1966-1982). The volume is an important cultural and political corrective to a 20th-century American tradition of political cartoons that long trafficked in racial stereotypes and stoked fear about immigrants, non-white populations, and Black radicalism.

Johnson (b. 1948) began his career as a political cartoonist as a precocious high schooler in Evanston, IL, after corresponding with the editor Lawrence Lariar and the New Yorker cartoonist Charles Barsotti. One of the best strips in the volume is a full-page panel from his high school newspaper, the Evanstonian, which encapsulates the ethos of 1965-66: a crowded lawn welcomes predictable comics cameos (Wonder Woman, Spider-Man, Thor, Charlie Brown, and Johnson himself, twice) alongside cultural icons and figures for a postwar society in crisis: a yé-yé-style band (“The Wurds”) butts up against a soldier holding a draft notice and a young man bearing a film reel for Lolita, not far from a “Central Council” door with the sign “Meeting in Progress” (Image 1, p. 10).

The volume is ordered chronologically, interspersing short prose reflections written by Johnson with his vintage comics, allowing the reader to track the artist's work alongside his autobiography. Johnson became increasingly steeped in radical politics after a memorable speech by the author and poet Amiri Baraka in 1969. Johnson was not directly involved in the Black Panther Party but taught student-run courses in Black Studies at Southern Illinois University before completing his doctorate at Stonybrook in 1988; he was tenured at the University of Washington in Seattle. Stylistically, Johnson’s drawing changes little over the course of the volume; his bulbous, black-and-white figures rely on caricature, with exaggerated afros, noses, and breasts, and his comics are almost entirely in single (or the occasional double) frames. His simple shading sometimes allows us to identify a character’s race, but sometimes even this is implied: a single shaded Black figure in the foreground suffices to characterize similarly outlined figures in the background. The chapter headings, which often display book covers or excerpts from newspaper articles, serve as a reminder that many of comics in this volume have been blown up and decontextualized from their original means of circulation. In the new prose segments, Johnson downplays his early political influences by underscoring his turn to continental and Eastern philosophies—especially—Buddhism later in life. The selection of comics itself, however, privileges his radical political cartoons, centering on questions of integration, racism, and Black people’s everyday lives (with the occasional one-off about aliens or newly-invented computers).

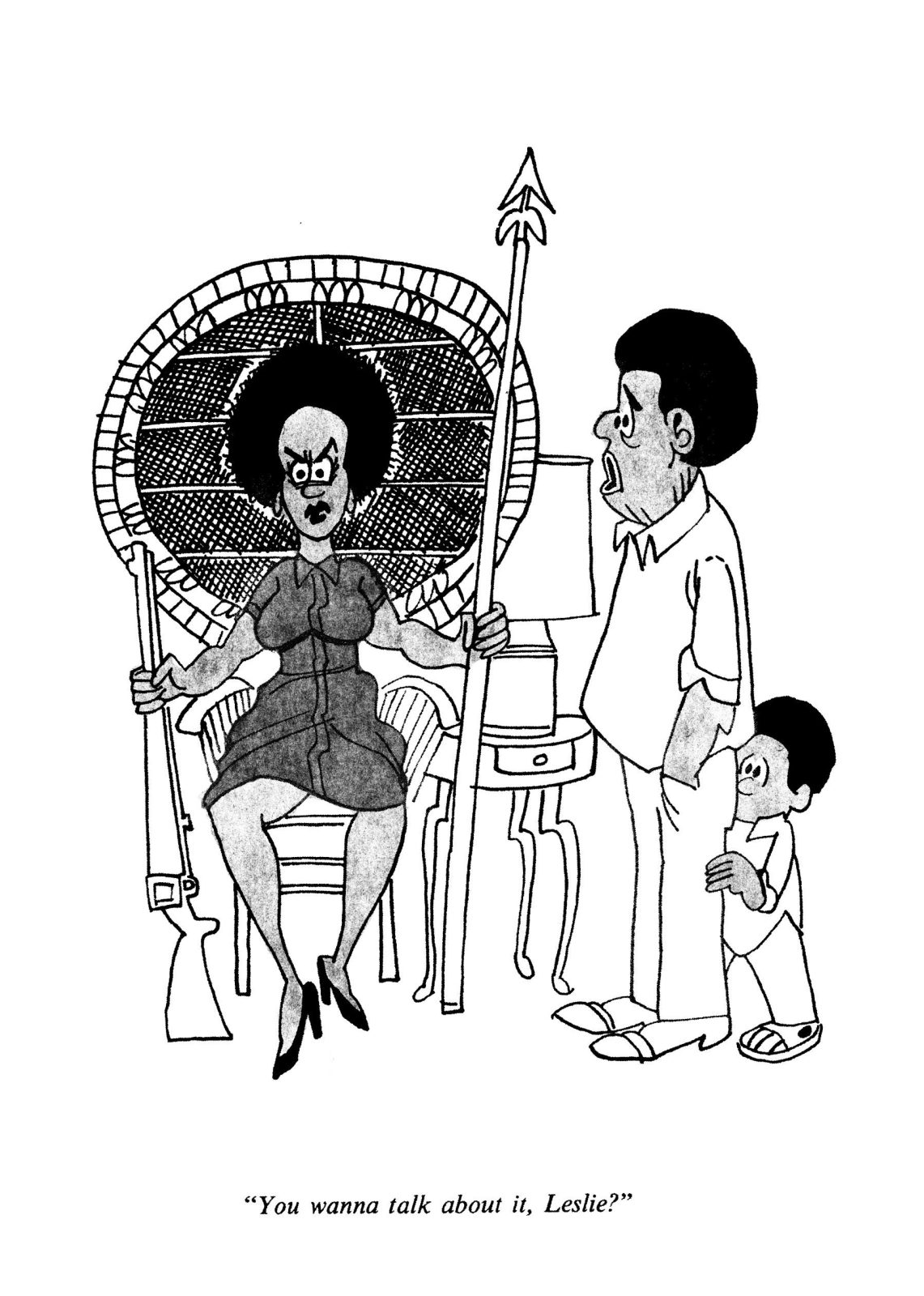

The majority of his political cartoons serve as an archive of a politically and socially situated humor: caricatures of the Black Panther Party. Writing as a non-member from Evanston or Stonybrook, Johnson provides a decentered vision of the Party, far from urban chapters in Oakland, Harlem, Washington D.C., and Chicago, and away from the media spotlight of Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, Kathleen & Eldridge Cleaver, or even Illinois chair Fred Hampton. While many strips share in their activist sensibilities, Johnson clearly approaches the Panthers from a distance, and his humor is directed both with and at them. One of Johnson’s go-to methods of gently mocking the Panthers is to resituate them in a domestic context: if one strip shows a woman refusing the police entry to her home because “the place is a mess,” others invert the patriarchal structure of the Party, by placing a spear-wielding woman on the iconic rattan throne (Image 2, p. 66).

An early and a late cartoon both play with the conceit of a Black Panther telling a bedtime story: one in which the wolf kills all the pigs (an obvious stand-in for the police) or another in which Marcus Garvey “beat mail fraud and moved black folks back to Africa,” a jest that makes fun of the popular enthusiasm for African repatriation (a dream that was nevertheless achieved by figures as important as W.E.B. Du Bois, who ended his life in Ghana) (Image 3, p. 188). This domestic humor is a good reminder that women played a vital role in the Black Panther Party. Women made up around 60% of members and were instrumental in social service programs—like free breakfasts, free ambulances, free clothing, and free busing to prisons—which are an often downplayed or overlooked part of the Panthers’ legacy. In this way, Johnson’s volume is all too timely, appearing alongside new works that seek to finally shine light on the Party’s women, like Ericka Huggins’ & Steven Shames’ Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party (ACC Art Books, 2022), which gathers testimonies from ex-members, alongside archival photographs by Shames. And yet, Johnson’s mockery of Party iconography and discourse reproduces a stereotype of the Panthers with which we are all too familiar: afro-and-beret-topped men often wear (bullet-laden) bandoliers and leather vests. If a woman in bed with a Panther wonders whether being “brothers and sisters” makes their actions incest, several gags delight in the imagery of the upright fist, which is variously wielded by a newborn baby, a cadaver, and several pallbearers (Image 4, p. 16). If Johnson’s strips re-domesticate male members and occasionally represent women as gun-toting Black radicals, in general, the strips reproduce the Party’s sexist vision of women as primarily lovers and mothers.

Some strips do tackle political hot topics surrounding the Party, like the US’s aggressive surveillance of Party members. In one frame, Panthers suspect that an FBI office is located below theirs (it is), and in another, an FBI informant is rumored to be among their ranks (drawn as a single white guy in a row of Black men). Still others upend readerly expectations by inverting racial and political common sense, like when a Black man at a podium addresses KKK members, asking “I suppose you're wondering why I've gathered you all here,” (Image 5, p. 62) or when a police officer willfully misunderstands “Power to the People” as a pro-union stance. Several cartoons anticipate the ongoing reality of police violence and discriminatory policing practices. Johnson even has a running gag where an unsuspecting Black man is mistaken for a Panther or is about to cross paths with police officers, who flank him around a corner.

That said, some of the best jokes take the Panthers’ political militancy seriously, by situating it within the discourse of Third-Worldist internationalism. See, for instance, a comic in which a Black man opens a volume by Frantz Fanon, the Martiniquan psychiatrist-turned-Algerian nationalism militant, only to be greeted with sputtering bullet fire: a straightforward visualization of the power of militant political theory, or of the transformation of theory into praxis (Image 6, p. 74). Or consider another in which a Black man buying matches carries a sign reading “Burn, burn, burn”; the joke hinges on the white shopkeeper’s anxious face and the very real threat of unspecified, possible vandalism. In yet another strip, a Black soldier by the name of “Jackson” shakes hands with a Vietnamese soldier—suggesting that Third-Worldist struggles transcend, and even override, American nationalism and imperialism. Johnson’s cartoon pairs, by which he occasionally revisits an earlier gag and redraws it, drive home this militant trajectory. If an early cartoon features a Black man balking at a white couple who wish to purchase an African safari, a later cartoon jests about Black militants seeking a group rate for flights to Algeria. That said, theorists and historians today would scoff at reducing the Panthers—and Third-Worldists, for that matter—to their advocacy of defensive or anticolonial violence; Fanon’s own endorsement of violence as a strategy for anti-colonial revolution has been overstated, because readers often were more familiar with Jean-Paul Sartre’s incendiary preface to The Wretched of the Earth (1961) than with the volume itself.

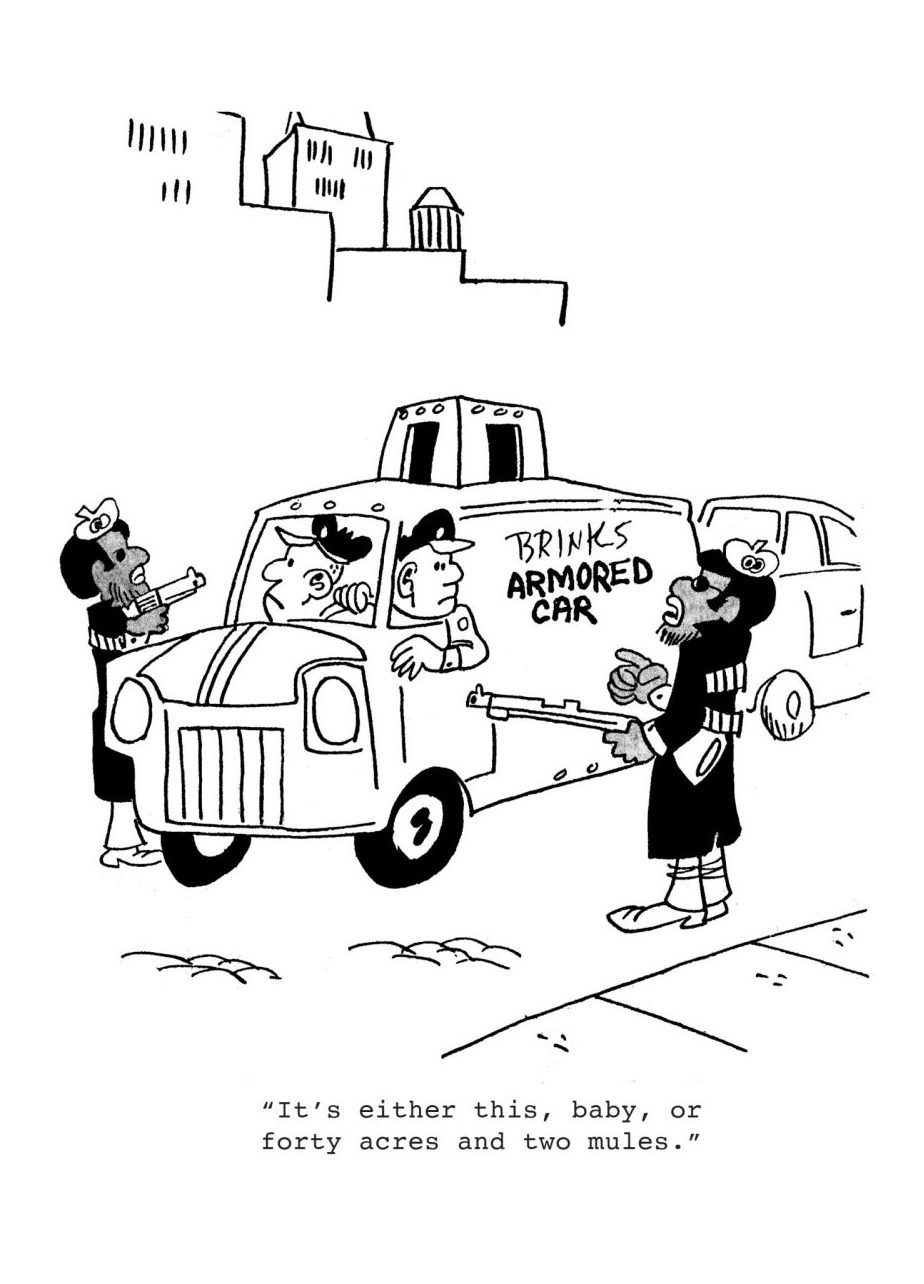

Johnson, in tandem with or anticipation of his literary and academic turn, tends to place his political humor within the longer historical realities of war and slavery. In one comic, set in a psychiatric office, a Black man speaking to a man dressed as Napoleon claims to suffer from a “Toussaint L'Ouverture” complex, referring to the Haitian revolutionary general who was crucial to the creation of the first Black free state. In another, a pair of Black men hold up an armored car, captioned “It’s either this, baby, or forty acres and two mules,” making light of Union allotments to freedmen and growing demands for reparations in the postwar era (and the 21st century) (Image 7, p. 134). What Johnson calls his “black humor” in the double sense of the term—both referring to Black culture and to caustic, bitter irony—shines in these historical invectives. Johnson’s satirical tone, and somewhat flippant engagement with Black nationalism, anticipates Aaron McGruder’s bestselling and controversial strip The Boondocks (1996-2006).

This is not to say that the whole volume has aged well or that it would be legible to readers unfamiliar with postwar America. Several jokes revive a sometimes-forgotten experience of casual microaggressions in newly-integrated workplaces (although enduring workplace racial microaggressions were, incidentally, a favorite topic of Brandon-Croft). The humor generally relies on treating Black people or Black Panthers as a relatively homogenous mass. Jokes about Black poverty (and rats) and Black Muslims mostly fall flat, perhaps because the realities of structural racism and violence towards religious minorities feel too real in the present. Occasionally, a joke disrupts Johnson's racial shorthand, as in a comic where each barber in a barbershop bears a different political position (“black culture,” “integration,” and “revolution”). Johnson’s more cringeworthy jokes are not totally wrong; he depicts white people and white supremacy as opportunistically pulling the strings (like a white man churning out blaxploitation books at home) and sheds light on political hypocrisy (like when a Black speechmaker equates integration with Uncle Tom, only to go home with his white girlfriend). But when Johnson mocks well-intentioned, although misguided, attempts to reappropriate African culture (in the use of Swahili or traditional dress), the joke no longer works, in part because such practices of reappropriation have dissipated or taken new forms in the new millennium.

These gentle critiques come as a reminder that humor shifts over time, but the power of the volume lies in the fact that much remains the same. One cannot but be curious about what Johnson would draw if he should return to comics today, after Black Lives Matter and in light of growing (and increasingly unabashed) neo-Nazi and white supremist movements. His sendups of the KKK resonate uncomfortably in the present moment, as do his jokes about police violence and structural racism. Too much of this volume is too familiar for comfort, a sign that Black lives continue to be undervalued and that we need his humor more than ever.

* * *

- A purist might point out that this excludes George Herriman, the artist of Krazy Kat (1913-1944), born of Louisianan Creoles of color, who had a lifetime contract with King Features Syndicate; Herriman scrupulously passed for white during his career, supposedly donning an iconic hat to cover what his peers took for his “Jewish” hair.

- See the introduction to Gateward’s & Jenning’s excellent collection The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Black Identity in Comics and Sequential Art (Rutgers University Press, 2015), pp. 1-15.

- See Susan E. Kirtley, Typical Girls: The Rhetoric of Womanhood in Comic Strips (Ohio State University Press, 2021), for further discussion of the history of Barbara Brandon-Croft and Black comic artists, pp. 18-23, 187-211.