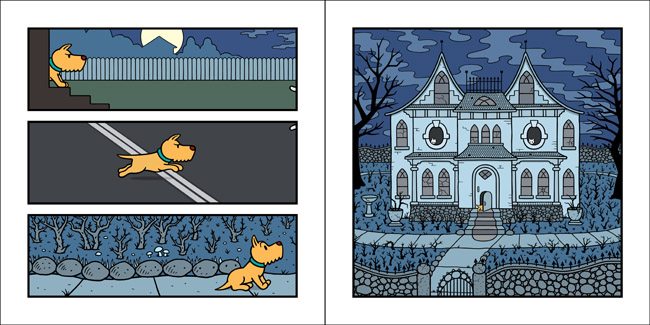

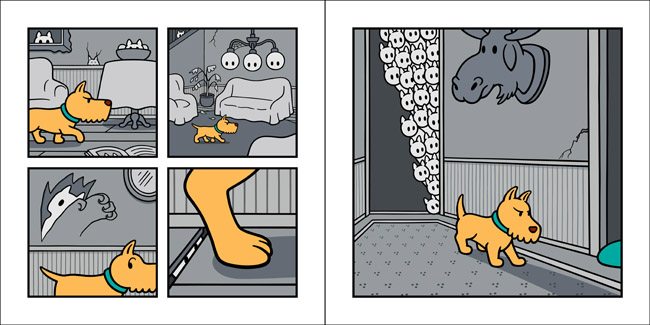

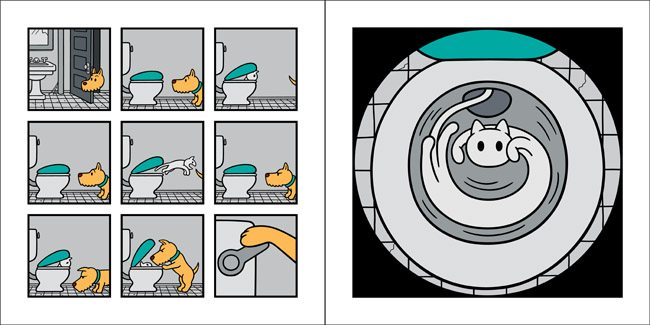

With clean lines, bold colors, and an elegantly precise design, Mark Newgarden and Megan Montague Cash’s Bow-Wow’s Nightmare Neighbors (Roaring Brook Press, Nov. 2014) marks the triumphant return of their intrepid terrier, last seen in Bow-Wow’s Colorful Life (2009). Like Bow-Wow Bugs a Bug (where their canine hero made his debut, in 2007), Bow-Wow’s Nightmare Neighbors is a wordless picture book that speaks the language of comics. Appropriately, the back cover’s cavalcade of blurbs includes luminaries from both picture books (Lane Smith, Mo Willems) and comics (Daniel Clowes, Chris Ware). Today, many people think of these as separate artistic realms, but the histories of comics and children’s books have always been intertwined.

Newgarden and Cash’s Bow-Wow stories remind us of this shared history — that, for example, comics pioneer Rodolphe Töpffer wrote his first comic, Les amours de Mr. Vieux Bois (1827), for the schoolboys he taught. And that, in the first half of the twentieth-century, many popular comics were reprinted as children’s books: indeed, Sunday strips of R.F. Outcault’s Buster Brown and Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy appeared in book versions with one panel per page, which is also a typical picture-book format. Newgarden and Cash’s Bow-Wow books underscore the fact not only that a fair few artists (Crockett Johnson, Syd Hoff, Tove Jansson) succeeded in both comics and children’s literature, but that many great picture books have relied upon the medium of comics to tell their stories: Maurice Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen (1970), David Weisner’s Tuesday (1991), and Régis Faller’s Polo books (2002-present), to name a few. In many respects, Bow-Wow’s Nightmare Neighbors embodies comics and picture books’ century-and-a-half of cross-pollination, and of finding smart ways to tell stories with pictures.

Via email, Cash and Newgarden spoke with me about their latest book, how they work together, their many influences, and how to tell stories without words.

Philip Nel: First there was Bow-Wow Bugs a Bug, and then the six Bow-Wow concept books (2007-2009). Now, five years later…Bow-Wow returns! Where has he been? (Since I know you both, I have some sense of why the long-awaited Bow-Wow’s Nightmare Neighbors [2014] was so many years in the making. However, on behalf of Bow-Wow fans everywhere, I had to ask…)

Mark Newgarden: There were several reasons for the gap between books. First, it took us awhile to come up with another long-form story that we felt was as strong about as Bow-Wow Bugs a Bug. Secondly, our original editor Tamson Weston (as well as the marketing and sales team) left Harcourt when that company was in flux and it made sense to move on to another publishing house. Fortunately Bow-Wow was adopted by Neal Porter and installed at his new kennel in the Flatiron building at Roaring Brook Press/ Macmillan. Thirdly, Bow-Wow’s Nightmare Neighbors grew into a much more involved and time-consuming project than any of our other books. At 64 pages, over 100 images and 0 words, this is far from a typical picture book.

Megan Montague Cash: And lastly, we have had some serious interruptions by some real-life nightmare neighbors. We live in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which now seems to be ground zero for all the new “luxury housing” in the universe. Dealing with a troublesome development project next door stole a great deal time away from our book (as well as the rest of our lives). These problems are a lot worse than Bow-Wow’s and so far, there is no real-life resolution like the one that we were able to imagine for him and the ghost cat mob from across the street.

Nel: I hope your happy ending also involves a long nap.

Newgarden: It will!

Nel: Your Bow-Wow books have a wonderful Ernie Bushmiller/Crockett Johnson/Otto Soglow iconic style, paring everything down to the basic visual language of the comic strip — the fence a series of long-stemmed “Y”s, the bug a black dot, and so on. What I wonder is: how do you get there? I mean, are you able to think in this language? Or do you, say, start with more detailed scenes that you then pare down?

Newgarden: As a cartoonist (and one who has been obsessed with comics and cartoons since early childhood) I think I’m just a native speaker. Before I could even read or write I filled reams of paper with little pictures for the stories I was telling myself in my head.

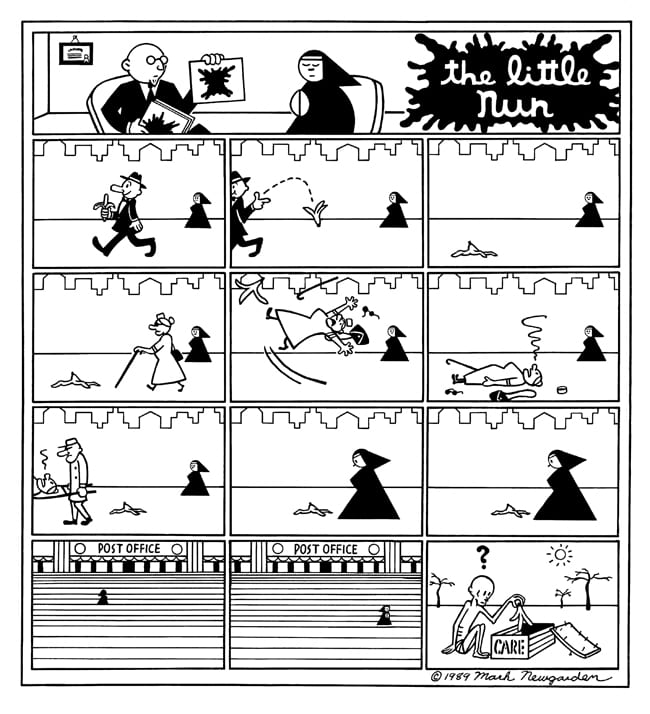

Mark Newgarden, “Love’s Savage Fury” (Raw, Vol 1. #7, 1986)

Back in the early 1980s I experimented with wordless strips for places like The East Village Eye using an ultra pared-down pictogram/international symbol approach. A couple of years later I expanded on that in The Little Nun episodes of my weekly syndicated New York Press strip. And I guess with Love’s Savage Fury, which originally ran in RAW magazine in 1986, one deliberate goal of that piece was that every single line must matter.

Megan has a background in graphic design and typography and her own illustration work often runs in a similar vein. So this was a real common ground where some of our working methods already met and a natural place for collaboration to brew.

When telling a wordless story the images really have to do all the work so they have to be extremely precise with no room for ambiguity. You literally DO write with pictures instead of words. There are natural parallels to the language of the pantomime comic strip and silent film but wordless comics in picture book format is really is its own beast.

Finding the right balance of information to include and how to delineate it is always a struggle. Wainscoting here? An extra ghost hairball there? There is a lot more visual detail in Bow-Wow’s Nightmare Neighbors than it’s predecessors and part of the job was wrestling with the images so those accumulated details and little gags would never distract from the narrative flow, but would hopefully enrich the mood and reveal themselves upon multiple readings.

Nel: Indeed, I wonder if you would be willing to share a glimpse of your process? Do you have earlier versions of, say, a page (or two-page spread) that would illuminate how you develop an idea or scene?

Newgarden and Cash:

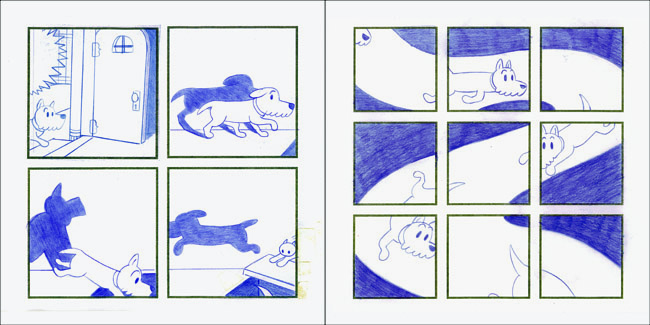

1. These are initial rough blue-pencil sketches for the “loose floor board” spread where Bow-Wow enters the ghost cats’ house and stumbles into an underground passage.

2. In our next draft, this left-hand page revision provided a cleaner, more visually direct solution.

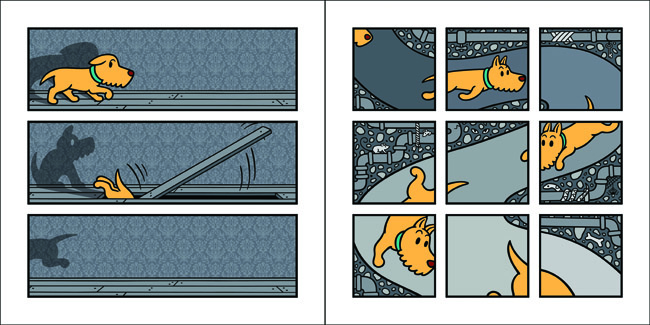

3. This is a tight pencil sketch which now includes some sub-strata “chicken fat” (and an authentic Victorian wallpaper pattern.)

4. And onto our finished work: the spread has been inked, scanned, vectorized, digitally refined and colored.

Nel: I also wonder about constructing the narrative itself. Like Bow-Wow Bugs a Bug, Bow-Wow’s Nightmare Neighbors is a model of storytelling economy, and is (I think) a bit faster-paced than its predecessor. Do you build the book around particular incidents? Does each book start out as a much longer narrative that you then pare down?

Newgarden: Bow-Wow’s Nightmare Neighbors at 64 pages was a more involved proposition than Bow-Wow Bugs a Bug (which was 48) so it’s gratifying to hear that it read at a faster pace for you. That was a goal, but no two readings are ever alike.

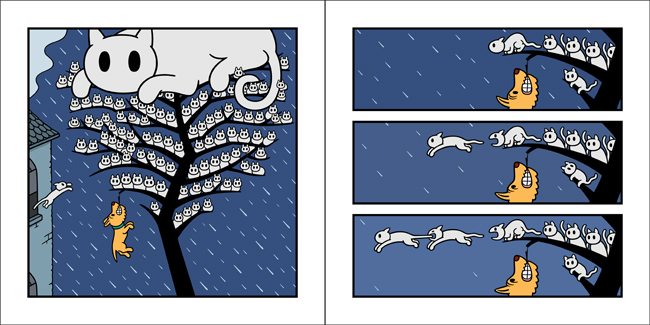

The pace might be inherent in the stories themselves though. In Bow-Wow Bugs a Bug a dog intently follows a little bug around the four corners of a square city block —and comedy ensues. In Nightmare Neighbors the dog is set on retrieving his stolen bed and heads directly across the street after the culprits. Once Bow-Wow crosses the street virtually every image propels the character forward — he is always moving right, pointing the reader towards the next page. The narrative stakes are higher and the reader’s cue to turn the next page is more insistent. It’s essentially a chase and return structure — sort of like Buster Keaton’s The General, except with dead cats instead of the Confederate army.

At a certain point a book starts writing itself and pretty much tells you how long it needs to be. With Nightmare Neighbors our aim was the same 48 pages, but well into the process, like it or not, it became clear that our story really needed an extra 16-page signature.

We had a few false starts in the very earliest drafts but once we got the dog into the haunted house it usually became pretty clear what would happen next. The challenge was to tell the story through successive gags, and to have every gag advance the story, advance the character physically through space and up the ante each time. To solve this we discovered that we really needed to work out the physical space of the cats’ house and plot Bow-Wow’s trajectory from basement to top floor over so many pages. For continuity reasons the space in which the whole book takes place had to be completely solid and plausible and we found ourselves drawing up blue prints and even making a small model of the house to get it all right. There was an awful lot of unseen work that had to happen so this book could be read as clearly and directly as possible. Years of effort went into in a book that, in theory, could be read in 45 seconds!

While Megan and I were working on Bow-Wow’s Nightmare Neighbors I was also collaborating with Paul Karasik on the upcoming How To Read Nancy a book-length expansion of our 1988 essay on comic strip structure. They are different kinds of books and aimed at different audiences but I think both projects inevitably influenced one another. I was doing a lot of focused thinking about how comic strips work best and the kind of profound choices that need to be made in executing the (apparently) simplest of images. Then I had to switch gears, roll up my sleeves and practice what I was preaching.

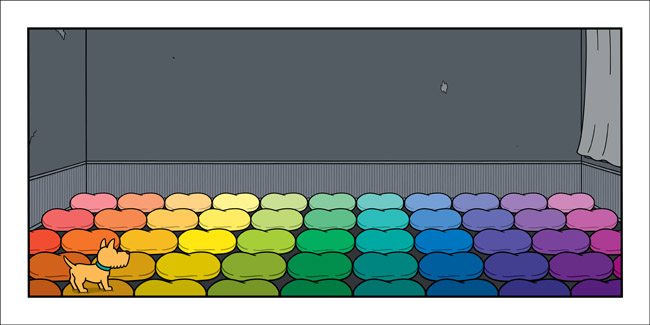

Cash: At one point, we were pretty far along with tight sketches and we were feeling pretty good about the story. But when we started addressing color, we realized we had a problem. The book was feeling too gray and dreary. That’s when we came up with the idea that seems like it should have come first – that Bow-Wow’s teal cushion was the single missing color in the spectrum of the ghost cat’s stash of stolen doggy-beds. A colorful oasis at the end of the grey desert was the right solution at a critical point in our story’s development. With any creative project, you always need to be ready to let go of what’s not working and be open to new ideas.

Nel: I’m so glad you brought up the cushions, which do help provide a warm, happy resolution. I was also struck by the fact that, though the book’s setting is a haunted house, the tone is light, humorous.

Newgarden: We like funny stuff!

Cash: In my sordid past as a freelance children’s book designer, I’ve worked on far scarier projects. These usually involved princesses, rainbows and licensed characters.

Nel: [Shudders.] Now, that is scary! On a happier subject, how do you and Mark work together? Leo and Diane Dillon often said that their work was truly collaborative — they couldn’t tell you what each person’s contribution was. But for other collaborators, the division of labor is a little more clear: Jon Scieszka (words), Lane Smith (art), Molly Leach (design). How do the two of you work?

Newgarden: We fall somewhere in between those scenarios. My background is as a cartoonist and writer. Megan’s is as a graphic designer and illustrator. I do more at the beginning (blueprints and framework). Megan does more in the middle (brick and mortar). Then at the end I become a house painter and as the book’s designer, Megan makes sure the entire structure is sound. But we wind up passing the work back and forth at each stage so many times that individual roles become blurry.

Cash: I think of our collaborative books as conjoined twins with one set of internal organs. We can definitively say that this arm is Mark’s (Bow-Wow’s reaction as an umbrella is pointed directly at his eyeball) or this leg is mine (a haunted house in the shape of a cat head) but then you get to the liver (collaborative work that is inextricably fused) you can’t make a separation. How can you say who’s responsible for the liver? You can’t because it’s equally shared. So it’s his arm. My leg. Our liver. That’s pretty much how I see our book partnership.

Nel: You’re the Chang and Eng of children’s books! Why has no one thought to use this as a blurb, I wonder? (Yes, as a child, I spent far too much time reading the Guinness Book of World Records…)

Cash: Yeah, I was fixated on that book too. Chang and Eng each had a body that was attached by a small band of flesh that joined their livers which were fused, but complete. If they’d been born today, they could have been separated, no problem.

Newgarden: Anyway, our one rule is if we can’t agree on something it doesn’t go in the book. That goes for the big picture but trickles down to smallest of details; the arc of an action line or the angle of a nail in the wall. Collaboration requires a lot of trust and a lot of patience. But the result is a better book than either of us could have created on our own.

Nel: Your different strengths and mutual willingness to cooperate makes the collaboration seamless. I assume, then, that the innovations in Bow-Wow’s Nightmare Neighbors emerged from the process, too? For example, Nightmare Neighbors was more intricate and metatextual than its predecessors (which, I expect, added considerably to the labor of making the book!). There are, for example, more double images: the haunted house that’s a cat’s face, the portrait whose hat and lock of hair resemble (upside-down) the ghost cat on the mat, torn wallpaper that is also a claw, or the Gothic Victorian wallpaper endpapers (featuring awake cats at front, and asleep at back). These add another layer to the reading — and re-reading — experience. It’s not only “let’s count the cats in this panel,” but a visual richness that I really enjoy. What inspired the proliferation of metapictures?

Newgarden: Some of these visual puns are integral to the storytelling. Others are just extra little gags. I think in part we wanted a book that could be read again and again yet still experienced in some new way. Which is a very tricky balance to strike in a wordless piece.

A haunted house that doubles as a cat’s head seemed like the perfect natural habitat for our gang of ghost cats. And of course its first appearance helps tip the reader off that this is not just any old dark house. The upside-down portrait established our running gag of Bow-Wow always mistaking another like-colored object for his stolen bed. To set this up effectively, we wanted to let the reader experience Bow-Wow’s POV and ensuing confusion the first time out. That made it easier for the subsequent confusion gags to register.

As for all of the funny little extras, in MAD magazine Harvey Kurtzman referred to those kind of visual surprises as “chicken fat.” Computer programmers call their versions “easter eggs.” Whatever you call them, they worked with the mood we were aiming at. The iconic haunted house is a traditionally dense, undependable locale and unnatural things naturally happen there. But we were also trying to add something different to our bag of tricks and create a more ambitious book.

As a kid, some of my very favorite picture books went there. I’m thinking specifically about the tree house party in P.D. Eastman’s Go, Dog. Go! and the sequences that pop up in all of Frank Tashlin’s books (for instance The Bear That Wasn’t or The Possum That Didn’t) where a spread is composed as a wall-to-wall panorama of concurrent individual visual gags. Our gag-laden ghost cat parlor is a sort of homage to those I guess- but also a chance to pass down the kind of imagery that excited me as a young reader.

Cash: As an author you only have so much control over how your work is received. You steer the book in the direction you want it to be perceived, but then reader takes over.

When I was young, if I came across a mistake or inconsistency in a book, I was personally offended. I took my picture books seriously and my feeling was if the grown up(s) who made the book couldn’t be bothered to get it together, I couldn’t be bothered with the book. Either the adults responsible for the book didn’t care or they had underestimated their readers’ intelligence. Both of those possibilities completely alienated me. I don’t remember the titles of any of these books because once I discovered an error, the book was basically dead to me. (We’re hoping for the opposite response.)

We heard about one little girl who kept Bow-Wow Bugs a Bug as her “comfort object”. This kid slept with the book and brought it everywhere and eventually it was completely beat to a pulp. That is the highest possible complement from any reader.

Nel: Another thing I enjoy about the Bow-Wow books is that they reveal your deep knowledge of children’s books, comics and early film comedies, but do so very subtly. You’ve absorbed this visual history so thoroughly that someone who also knows some of the history might spot an influence (Ernie Bushmiller! Tex Avery! Buster Keaton!), but most readers will simply enjoy the books, unaware of how all you’ve learned made them possible. Which particular works — from children’s books, comics, or early film — have been most influential on Bow Wow’s Nightmare Neighbors? What did you learn from those works?

Newgarden: I guess my immersion in 20th century pop culture, especially humor culture, is so much a part of my DNA that it’s pretty hard for me to isolate individual strands.

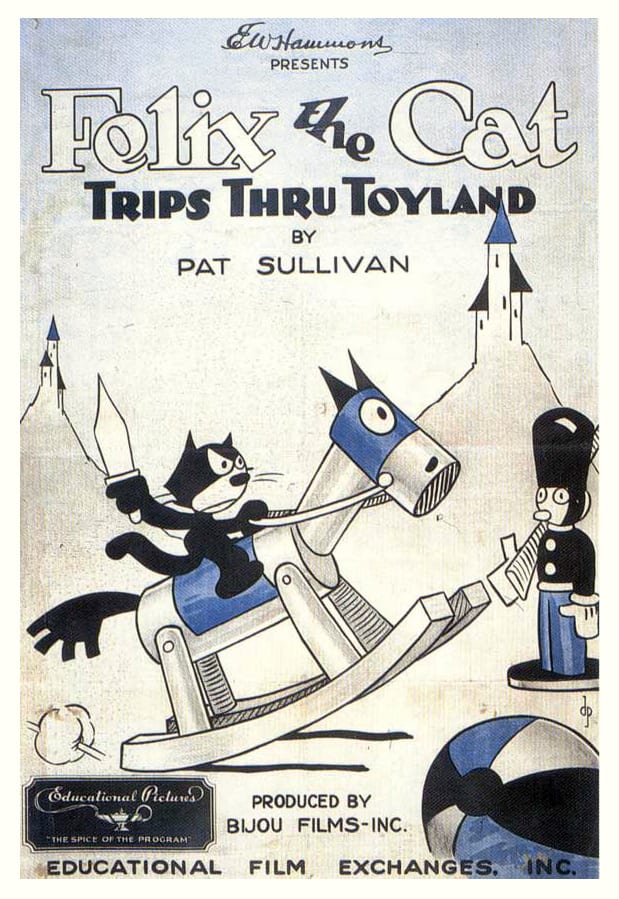

One example I can think of though, is that our alliterative book titles are a little nod to the titles of the original silent era Felix the Cat cartoons— which to me are exemplars of the gag-driven visual narrative. The poster for Felix Trips Thru Toyland has hung on my studio wall throughout all of these projects.

In the early stages of Nightmare Neighbors I did intentionally revisit a number of classic spooky films and cartoons — from Melies to The Three Stooges — to get a refresher course in exactly what elements constitute THE iconic haunted house. One perk of the kids’ book biz is that you can go with the iconic (or even with the cliché) yet it’s all brand new to your readers. And they will always remember where they first saw the hidden panel or the antique portrait with the cut-out eyes! I like to think that of all my stuff contributes to a long, venerable tradition of something or other. But on the design end of things, Megan probably did more actual hands-on research for this project.

Cash: I studied the main title treatment for science fiction and horror movies in preparation for our type treatment. The Wolfman, The Thing, Them!, The Mask of Satan, and She Wolf of London were all in the ballpark of what we wanted. “Tales of Tomorrow (a science fiction TV show from the 1950s that I’d never heard of) came closest to the hand lettering I ultimately designed for Nightmare. (Thank you, Google image search!)

I researched Victorian architecture, furniture and wallpaper. LOTS of wallpaper! Then I had to play interior decorator and figure out which choices worked with our house’s logistics and which didn’t. Clarity and storytelling were always the biggest deciding factors in what made the final cut. And sometimes an object or a detail would instigate a specific story twist that wasn’t there before.

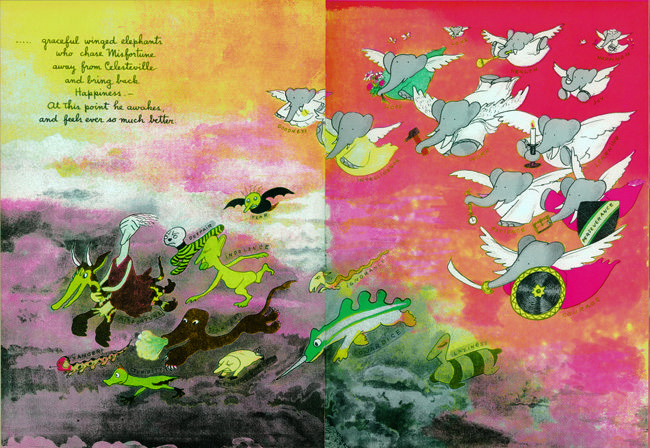

All sorts of visual stimulation are nourishment to any artist. I went back to spooky books that had an impact on me when I was a kid. The terrifying nightmare in Jean de Brunhoff’s Babar the King. The older sister chasing away her little brother’s nightmare in Charlotte Zolotow’s and Garth Williams’ Do You Know What I’ll Do?. And of course Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are falls solidly into that category. Hilaire Belloc’s Bad Child’s Book of Beasts was very dark and went out of its way to insult the reader, but as a child, I loved it. And Tomi Ungerer’s The Three Robbers shocked, then satisfied me.

Nel: Mark, you once told me that, when you and Megan were planning to write your first co-authored picture book, you studied Dr. Seuss. What did you both learn from Seuss? And did his works shape your approach to visual storytelling at all?

Newgarden: To anyone of our generation, Seuss is the dictionary definition of the “perfect” kids book creator. When Megan and I first started to think about making books together I went back to Seuss and really studied the canon- especially his word-to-picture ratio (in the non-Beginner Book titles, that is.) We worked up a series and based our text on that ratio.

To our dismay almost every editorial reaction was identical: “Too many words!” When I explained that I deliberately went to the master for that word-count almost every reaction was equally identical: “Dr. Seuss!? Well if he was just starting out now he could NEVER be published today!” So we both learned that according to the wisdom of the current modern children’s book industry Dr. Seuss did everything wrong!

“Too many words!” led to “OK—Let’s show them something where they can’t say ‘too many words!’” Which led to Bow-Wow. But we plan on getting back to our “too many words!” project. It’s a funny series with funny words and we came close at least three different times before an editor left to become an oceanographic attorney or a publishing house was acquired. Hopefully “too many words!” will be back in fashion in time for our next go-round.

Cash: Some people might think Seuss had too much of an agenda. A lot of current picture book material is so over-sanitized, rigidly formatted, and painfully commercial, there’s nothing left that feels authentic. I mean, our lives are not all pink and sparkly and wonderful. Picture books should reflect a range of human experience. Kids know the difference between being spoken to and being spoken down to.

Nel: Happily, the Bow-Wow books enter a publishing landscape in which comics-for-young readers are being taken more seriously, published on good quality paper in handsome hardback books. Sticking solely to the wordless ones, my favorite contemporary works are your Bow-Wow books, Regis Faller’s Polo books, and Barbara Lehman’s books (The Red Book, Rainstorm, etc.). What are your favorite comics for young readers? They don’t have to be wordless, and nor do they have to be contemporary (I know it can be hard for artists to draw up a list of their favorite artists — concern that omission might be interpreted as a slight, among other reasons).

Newgarden: They should start with the classics. Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy immediately comes to mind. I’m sure that strip is where I learned to read—both words and pictures. Depending on the kid, I’d recommend Peanuts, Thimble Theater and Little Lulu. And if they get hooked, then onto McCay, Herriman and all the rest!

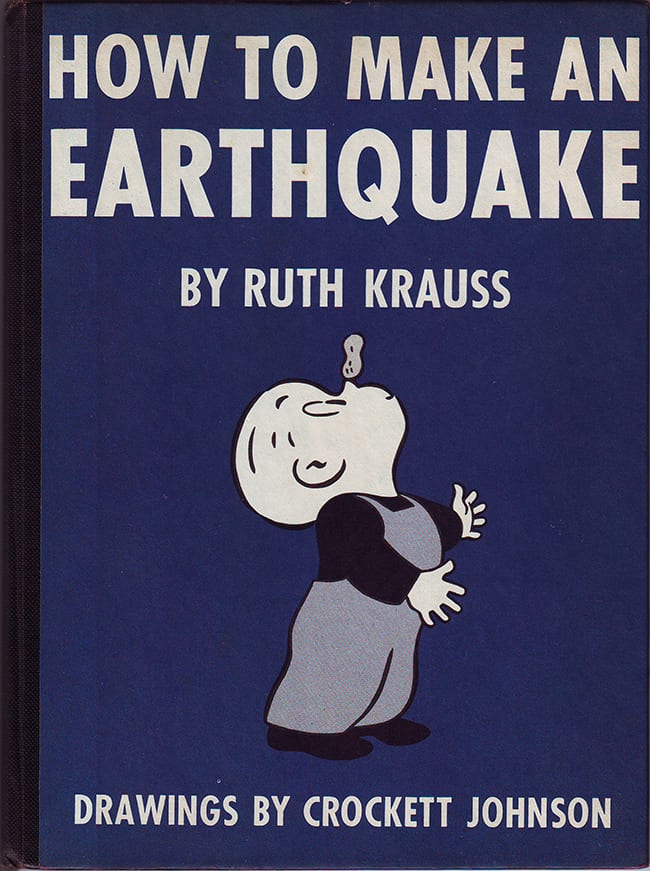

Cash: Mark’s the bigger comics reader. I’m more of a picture book person so I’ll just go ahead and add my two cents on that topic. When I was four I was obsessed with Play with Me by Marie Hall Ets. Anything by Ruth Krauss (and especially How to Make an Earthquake illustrated by Crockett Johnson). Munro Leaf (especially Robert Francis Weatherbee: The Boy Who Would Not Go to School). Books illustrated by Lane Smith and designed by Molly Leach. Books by Richard McGuire. Books by Mo Willems (especially when there’s a pigeon involved). Polar Bear Night illustrated by Steven Savage. The Curious Garden by Peter Brown. Of course there are lots of other children’s books that are essential. But how can I list them all?

Nel: What does the future hold for Bow-Wow? More books, I hope?

Newgarden: We do have another Bow-Wow project in the pipeline titled Bow-Wow’s Curious Comics. It’s a different kind of book, based on the classic format of full-page Sunday newspaper comics. So it will feature many self-contained gags rather than a continuous story.

Cash: As we mentioned earlier, wordless books can take a long time to bring into the world. We’d like to spread our wings with other formats, characters and series. But as long as our books are so well received, we don’t think Bow-Wow will be retiring any time soon.

Bow-Wow’s Nightmare Neighbors will debut at Comic Arts Brooklyn (CAB) on November 8. CAB is held at Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church, 275 North 8th Street in Williamsburg Brooklyn and is free and open to the public from 11:00 AM to 7:00 PM.

Newgarden and Cash will be signing books at table 2 (upstairs).