“Brilliant student...Art addict...Romanticist...Little men in raccoon coats” reads the thumbnail sketch of Edward Gorey, budding artist, in his high-school yearbook. We know Gorey as the author and illustrator of a hundred-odd little picture books, entries in a one-man genre: the Goreyesque. Somewhere between ironic-gothic and camp-macabre, it crosses Edward Lear with Lizzie Borden, Agatha Christie with Waiting for Godot, a Surrealist sense of the strangeness lurking in everyday life with the dreamlike atmosphere of Fantômas, Louis Feuillade’s silent serial about an absurdist master criminal. In 1942, though, Gorey was just 17-year-old Ted, as his classmates knew him, a senior at the progressive Francis W. Parker School in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood. Still, he’d already gained a reputation for eccentricity—he once painted his toenails green and went for a stroll, barefoot, down Michigan Avenue—and for his artistic talent, on display in murals for high-school dances, sets for the senior play, and the queer little men who populated his doodles.

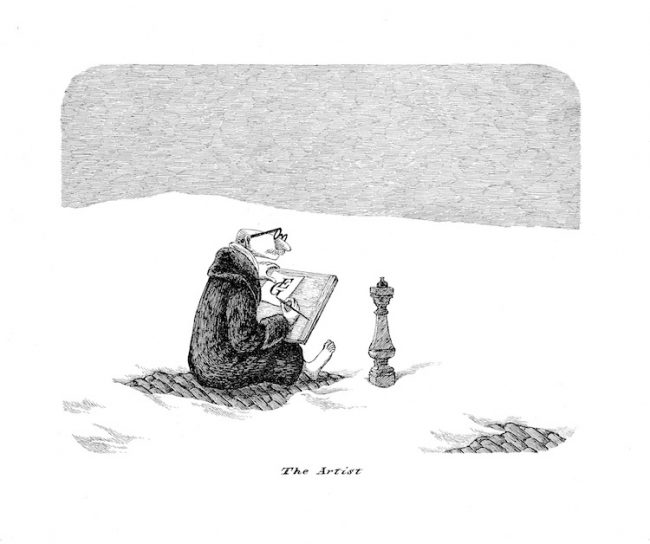

Cartoon alter egos, they personify Gorey’s sympathy for all things Victorian-Edwardian and his affinity for Aestheticism (hence the fur coats, in homage to Oscar Wilde). Their curiously elongated heads give them a whippetlike appearance; their lack of a mouth makes them inscrutable—or would, if their perpetually popeyed expression and furrowed brows didn’t make them look so fretful, or as Gorey would say, in his 1890’s way, “distrait.”

Gorey’s little men proliferate on the backs of his Harvard term papers, striking attitudes in astrakhan coats and Victorian bathing costumes. But it isn’t until his first book, The Unstrung Harp (1953), that they make their public debut in the person of Clavius Frederick Earbrass, world-class neurotic and hopelessly blocked writer. Famously described by Gorey as a “Victorian novel all scrunched up,” T.U.H. chronicles the difficult birth of the titular work as Earbrass mopes around his country manor, Hobbies Odd, “near Collapsed Pudding in Mortshire,” driven to distraction by his tangled plot, tiresome characters, and “the unexquisite agony of writing when it all turns out drivel.”

After The Unstrung Harp, Gorey retired his otter-headed Victorian-Edwardian gent, and with him the more overtly cartoony aspects of his aesthetic. In his grammar-school days, he’d turned out single-panel gags drawn in an amateurish approximation of the reigning style of the day (think: ‘30s strips like Mutt and Jeff, Gasoline Alley). Seven years as a designer and illustrator at Doubleday’s quality-paperback imprint, Anchor Books—from 1953 to ‘60—scrubbed the Sunday-funny jokiness from his style, though his mature work always retained elements of caricature and visual humor (the product, in part, of his passion for 19th-century newspaper cartoonists like J. J. Grandville and children’s book illustrators like John Tenniel).

Now, two decades after Gorey’s death, his funny little men are back in The Angel, The Automobilist, and Eighteen Others, published on April 1 by Pomegranate. Described in the flap copy as an “early collection of distinctive drawings,” it’s an Earbrass family album: 19 portraits of the consternated chap in various guises. (Not 20, as the title promises; chalk it up to Goreyan whimsy. Or contrarianism. Or something.) There’s an Automobilist stopping to contemplate an Earbrass-headed sphinx in a cemetery reminiscent of Mount Auburn (where Gorey, during his Harvard days, used to stroll among the cenotaphs and obelisks, Victorian funerary monuments that would later recur in his work); a Wretch wearing a sandwich board advertising “Evil Communications”; a Suicide seen beneath a cloud-shrouded moon, poised for his leap into oblivion; an ennui-stricken Ennuyé, lounging, improbably, on a pool table; and so on.

The Angel, The Automobilist isn’t exactly the Salvator Mundi of Gorey studies. Found among Gorey’s papers after his death by Andreas Brown, his longtime publisher and promoter, it’s a charming trifle—sketches in search of a story, in the manner of Leaves From a Mislaid Album (included in the Gorey anthology Amphigorey Too). (Gregory Hischak, director of the Edward Gorey House museum on Cape Cod, wonders if the drawings weren’t just “portfolio pieces that he assembled” to land his job at Doubleday.) To be sure, any new Gorey is good Gorey, but The Angel doesn’t add much to our understanding of his work (though it’s a thrilling indicator that the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust, which administers his copyright, is newly invigorated by the appointment of Eric Sherman, Brown’s lawyer, as a trustee).

That said, the book’s family resemblance to those omnibuses of classic New Yorker cartoons resurrects the question of what debt, if any, Gorey owes the comics medium. Are his little “Victorian novels all scrunched up” vest-pocket graphic novels—works of sequential art whose philosophical profundity, psychological depth, narrative complexity, and artistic sophistication elevate them to the status of so-called serious literature?

As a kid growing up in 1930’s Chicago, Gorey was a devoted reader of newspaper strips. (“I get all the Sunday funnies, but I want you to send down the everyday ones,” he urged his mother, in a letter sent when he was staying with his grandparents in Florida in 1932.[1]) He was a fan of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat and of Don Marquis’s Archy and Mehitabel, both staples of the funny pages in his grammar-school years. His juvenilia proclaim the influence of comics and cartoons, especially his anthropomorphic felines, who bear a strong resemblance to Otto Messmer’s Felix the Cat.[2]

Though his style, post-Unstrung Harp, was less cartoonish, Gorey never outgrew his appetite for the medium. In a 1994 interview, he was effusive about the Fox Kids show Batman: The Animated Series, a stylishly dark cartoon whose aesthetic nodded to Deco, noir, and German Expressionism. (Gorey was 69 at the time.) “I really very much admire it,” he said, especially “the dark, simplistic quality of it. I’m not going to say, ‘I’m going to do something in the vein of Batman, but at the same time it’s sort of in the back of my mind.”[3]

His library, at the time of his death, included anthologies of Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes, Gary Larson’s Far Side, the droll caricatures of Ronald Searle, European comics like Astérix and Tintin (Hergé’s ligne claire aesthetic surely chimed, in Gorey’s mind, with the crisp line of his own hand-drawn “engravings”), 12 volumes of Hyperion’s Library of Classic American Comic Strips, Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo, and Wilhelm Busch’s classic Max and Moritz (1865), a black-comedy parody of moralizing children’s literature like Heinrich Hoffmann’s macabre Struwwelpeter (1845). Predictably, his small but carefully curated (as we’re taught to say) collection of original art included cartoons by Glen Baxter and the loopy New Yorker stalwart George Booth. Less predictably, his bookshelves were stuffed, too, with collections of superhero comics, especially Marvel titles: Batman from the 30s to the 70s, Superman Battles the Mightiest Men in the Universe, Bring on the Bad Guys: Origins of Marvel Villains, Marvel’s Greatest Superhero Battles, The Silver Surfer, The Incredible Hulk, and on and on.

Gorey’s fondness for comics and cartoons isn’t proof positive they influenced his work, but Steven Heller, a historian of design and illustration, has no doubt he has a foot in the comic-art tradition. Gorey was “a master of a genre of graphic storytelling,” Heller believes, a genre he defines as “a synthesis of the comic book and the graphic novel”—in short, “a picture book for adults.”[4] Scott McCloud goes even further. Arguing against what he sees as the pervasive unwillingness to call a comic a comic for fear it will stamp the work in question as kids’ stuff, he claims Gorey as one of the medium’s “neglected masters.”[5] “The moment that comics become too adventurous, or too innovative, they cease to be ‘comics’” in the public mind, asserts McCloud. “I heard an interview with Edward Gorey, and the word ‘comics’ never even came up—even though the man has done virtually nothing that isn’t comics! It’s insane.”

The fly in the ointment, of course, is that Gorey never cited comic books or graphic novels as points of reference, whereas he often mentioned silent movies, Victorian engravings, and Max Ernst’s collage novels. Then, too, there are idiomatic differences that set Gorey’s work apart from the comics medium. For example, his world is silent: there are no word balloons, no sound effects. And no cinematic motion: movement is subtly implied in Gorey’s drawings, not hyperbolically depicted with the punch-in-the-face dynamism of superhero artists like Jack Kirby and John Romita, Sr. Most important, Gorey only occasionally uses the panel format that, in the popular mind, is the distinguishing characteristic of comic strips and comic books. This, in turn, means that he doesn’t exploit the white spaces between panels, a device used to stunning effect by masters of the medium like Alison Bechdel.

To be sure, Gorey titles like The Doubtful Guest and The Willowdale Handcar resemble comics in their use of what McCloud, in Understanding Comics, calls “scene-to-scene transitions that transport us across significant distances of time and space.”[6] Likewise, genre-bending Gorey works like The West Wing, a wordless montage of movie still-like scenes set in a haunted house, employ McCloud’s “aspect-to-aspect” transitions, which cast “a wandering eye on different aspects of a place, idea, or mood.” As well, Gorey makes use, in books like The Object-Lesson and The Raging Tide, of the comic scholar’s “non-sequitur” transitions, which offer “no logical relationship between panels whatsoever.”[7]

Maybe we’re overthinking this. Whatever else they are, Gorey’s books are picture books, so why not just call them that, especially since the term “comics” still carries a lot of baggage, at least among art critics and literary mandarins?

Jeet Heer, the comics historian, locates Gorey on the timeline of what he calls the “proto-graphic novel,” a form that includes the wordless yet starkly powerful woodcut “novels” of Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward and the embryonic comic books published by the Swiss caricaturist Rodolphe Töpffer in the early 19th century, humorous stories told in captioned panels. (It should come as no surprise that Gorey owned a couple of Töpffer’s books.)

Mark Newgarden, a cartoonist who writes about comics, doesn’t doubt that wordless novels helped pave the way for Gorey’s little books but notes that they arrived on the heels of a “slew of more aggressively ‘adult’ picture books” such as “the semi-abstract captioned drawing collections” by magazine illustrators like William Steig and Abner Dean, as well as titles like It Shouldn’t Happen (1945) by Don Freeman, “which doesn’t resemble Gorey in the least but does strike a similar picture-book balance between words and pictures. Something was in the air. R.O. Blechman’s Juggler of Our Lady and The Unstrung Harp pop up in 1953.”[8]

He wonders, too, if ‘50s readers weren’t primed for Gorey’s ironic, Victorian-Edwardian style by “the 1920s-‘30s vogue of Victorian-era parody cartoons” associated with S.J. Perelman and John Held (whose books Gorey owned),[9] a “gay-‘90s nostalgia/irony” that by the ‘30s and ‘40s had “found its way deep into the mainstream media”—namely, the funnies, which an impressionable young Gorey, aspiring cartoonist, was devouring, right about then.[10]

But whereas these progenitors gave pride of place to the image, sometimes to the exclusion of the word altogether, Gorey, with rare exception, strikes a perfect balance between the two. What he and other proto-graphic novelists have in common, Heer thinks, is that they “tend to come from a background outside of commercial comic strips or comic books, either from the fine arts, from children’s literature, or from avant-garde literature”; their work tends “to be allegorical or dream-like rather than realistic”; and their books appear, in their moment, as “isolated mutations, freaks of nature” yet look, in retrospect, like part of a “quirky, wayward” tradition that leads, ultimately, to the graphic novel—descriptions that fit Gorey to a “T.”[11]

Certainly, if Gorey’s little books are picture books, they’re picture books of a highly unconventional sort, capable of the heavy artistic lifting we associate with the best comics and graphic novels. Even a bonbon like The Angel, The Automobilist is more substantial than it seems at first bite. Seen as a gallery of alter egos, it sheds light on Gorey’s secret selves.

A master of the frivolous and the nonchalant, Gorey deftly deflected interviewers’ attempts to unriddle the mysteries of his inner life. His enigmatic sexuality, the source of considerable speculation, was decidedly off-limits. Though he lived alone, had only a handful of crushes—all of them same-sex—that never blossomed into full-fledged relationships, and claimed, with typical inscrutability, to be “neither one thing nor the other particularly,” his campy delivery was a textbook example of stereotypic pre-Stonewall gayness, as were his artistic passions and cultural deities: the ballet, Bette Davis, Marlene Dietrich, silent movies, Oscar Wilde, the viciously witty novels of the gay British satirists E.F. Benson, Ivy Compton-Burnett, and Ronald Firbank. The gay subtext of some of his books (The Curious Sofa, L’Heure Bleue) and book covers (for Herman Melville’s Redburn and A Room in Chelsea Square by Michael Nelson) is hidden in plain sight.

Whether Gorey was a closeted gay man, a homoromantic asexual, or simply someone who categorically refused to be categorized was, and remains, a locked room in the Gorey psyche. Even so, his Earbrass Man, as fans have come to call him, offers oblique hints about the hidden Gorey. In The Angel as in The Unstrung Harp, and on Gorey’s holiday cards and the watercolors that adorned the envelopes of his letters, Earbrass and his clones occupy an exclusively male social world, as Gorey did at Harvard and in New York, where his social circles were overwhelmingly gay. Typically, we see the Earbrasses in chummy interactions that imply intimacy (whether romantic or merely bromantic, who knows). When they’re not engaged in me-and-my-shadow routines, each mirroring the other, they’re marooned, like C.F. Earbrass in his mansion, in a solipsistic universe populated solely by Earbrass lookalikes, and where even decorative figurines on motorcars and door-knockers have Earbrass heads.

Are Gorey’s identical-twin couples of Victorian-Edwardian gents a lovelorn gay oddballs’s dream of the perfect match? Or an only child and lifelong solitary’s fantasy of a BFF? Or are his twinned Earbrasses, like the doubles meeting on a shadowy street in the Angel panel captioned “The Doubleganger,” symbols of a double life—a life lived with one foot out of the closet, one in? Or are they Goreyan shorthand for his yin-yang self? The face he showed the world was chatty, insouciant, quick with a witty quip. Yet he was prey, in the sleepless watches of the night, to a piercing melancholy. (“Having got into bed and turned out the light, I quietly burst into tears because I am not a good person,” he confessed, without explanation, to his friend and children’s book collaborator Peter Neumeyer, in one of the letters collected in Floating Worlds: The Letters of Edward Gorey & Peter F. Neumeyer.)

Speaking of yin-yang, Gorey was a devotee of Taoism, the ancient Chinese philosophy that teaches the importance of dualistic opposites in maintaining cosmic balance. In The Angel, the Earbrass Man wears many faces, some sides of the same dualistic coin: sublime Angel/profane Wretch, passionate Sybarite/ voyeuristic Watcher, bored-to-tears Ennuyé/ardent Devotee.

In a downstairs sitting room, in the rambling old house near Barnstable harbor where Gorey summered with his cousins before moving to Yarmouth Port, hang three early Goreys, untitled early studies of the Earbrass character who would later step onstage in The Unstrung Harp. Each set of minutely detailed portraits is a variation on the doppleganger theme, pairing mirror images of baldheaded, quizzical men in turn-of-the-century garb.

Or, rather, near mirror images, because as Ken Morton, Gorey’s first cousin once removed, points out, each Earbrass differs subtly from his mate. “They’re all in opposition, in various ways,” he says. Look closely at the Earbrass in the fur-collared overcoat peering at the Earbrass in the smoking jacket, each regarding the other with the stricken look that all Earbrasses wear, and you’ll see that the one on the left is missing his right foot, while the one on the right has no left hand. In another set of what looks at first glance like identical twins, the Earbrasses on the right have canes and are standing back to back; those on the left have none, and are face-to-face. And so on.

Morton, who knew cousin Ted well, reads the series as a Taoist essay on “the various ways that things can be opposed.” That works. Or did Gorey intend us to see them as incarnations of the spirit of paradox and ambiguity that animates the camp-uncanny aesthetic we call the Goreyesque? Then again, we can see them as Portraits of the Artist as a Split Self—reflections of a man who contained multitudes, had little patience with the binary-minded, and, let us never forget, loved a good mystery.

—Mark Dery is a cultural critic and the author of four books, the most recent of which is the biography, Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey.

[1] http://www.lib.luc.edu/specialcollections/exhibits/show/gorey/education

[2] Gorey’s boyhood collection of Felix the Cat merchandise—buttons, figurines, a Felix watch—is on display at the Edward Gorey House museum.

[3] August 1994 interview with Clifford Ross, reprinted in The World of Edward Gorey.

[4] Steve Heller, “The Whole Gorey Story,” The New York Times, September 1, 1996, Section 7, 7.

[5] Stanley Wiater and Stephen R. Bissette, “Scott McCloud: Understanding Comics” in Comic Book Rebels (New York: Donald I. Fine, Inc., 1993), 10.

[6] Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, 71.

[7] Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, 72.

[8] Mark Newgarden, e-mail to the author, December 23, 2016, 1:39 P.M.

[9] Mark Newgarden, ibid.

[10] Mark Newgarden, e-mail to the author, December 23, 2016, 4:15 P.M.

[11] All Jeet Heer quotes from e-mail correspondence with the author, October 2014, and from Jeet Heer, "The Proto-Graphic Novel: Notes on a Form,” Comics Comics Mag, October 19, 2009, http://comicscomicsmag.com/?p=