Do you feel that the book format is a more successful format for the material?

Well, I’m the last one to judge that, but my intent was to not just do the easy thing, which would have been to collect the twenty strips in order and slap a cover on it and say “Here are those strips I did for The New York Times Magazine.” I wish I could have done that, because it would have saved me five months of work, and it probably doesn’t matter to anybody, but I wanted it to be an experience that was a book. I wanted it to justify being in a book.

I thought of it in the way that you might re-edit a film. You might have two editors that would approach the exact same film in two different ways and think of the story differently. I thought of how David Lynch took an hour-long pilot for Mulholland Dr. and turned it into a feature film. I’ve seen the pilot, and it’s very similar and it’s got all the same scenes, and yet it’s very, very different from the final film. Just these tiny little things—he’d shave off a little bit of a scene, or extend a scene, and all of a sudden it had a completely different effect. I was really inspired by the idea of being able to do editing in comics, being able to play around with the time structure of the story and make it work as a single-sitting experience.

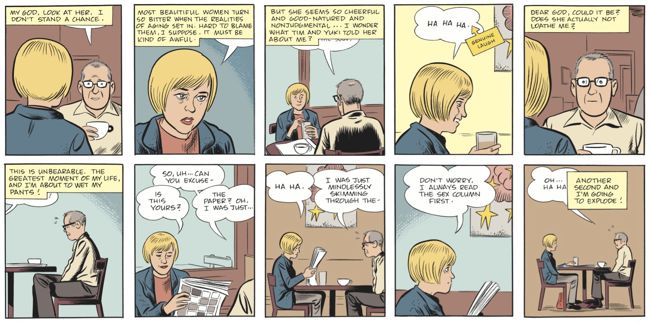

One of the most noticeable differences between the two formats is that because the original pages have, for the most part, been split in half and placed on opposite sides of a spread, with occasional new material spliced in between, the punchline/cliffhanger construction of the original has been diluted. When I first read the story, that set-up had an effect on me as a reader: “Ah, this is really funny! It’s really vicious! He’s a jerk, he’s self-absorbed.” As time went on and more was revealed about him, I softened somewhat. But in the book, maybe because it doesn’t hit so hard on the yuks at the end of every page, he’s more sympathetic from the start.

I think there’s something to be said for that. Also, certainly, if you read Wilson after you read the Mister Wonderful strip, Marshall’s a Boy Scout compared to Wilson.

[Laughs] Exactly!

He at least has some self awareness. Or he’s trying to be polite, in some scenes. [Laughs]

Do you feel that you lost anything in going from the single-page strip format to the way you arranged it in the book?

Not really, because as you say, the thing I did was soften the punchlines. To me, the punchlines were just a device to make it work in the weekly strip format. I wanted to have a certain rhythm, where you got to the end of something that was also promising more in the next strip. That’s really a gimmick, in many ways, or a trick. It was fun to try to play with that, and to imagine somebody actually reading the last panel and saying, “Boy, I can’t wait to see what happens to Marshall next week!” Which I doubt ever happened. [Laughs] But the story itself doesn’t need that, and it’s not about that. So I’m much happier with the book version. But I’m a book person, so that’s always the ultimate goal: to get it right in book form or comic form.

Along with rearranging the original strips, you also added some new material, much of which comes in the form of big single-image spreads. Those make a big impact. That big close-up on Marshall’s eyes as he says, “Oh my God oh my God oh my God!” for example. Have you ever worked at that scale before?

No, not at all. It was a very weird format to work in. [Laughs] I do the originals a little more than twice as big as the printed pages, and that one, you couldn’t even really tell what it was up close. You’re just looking at these orbs and shapes. [Laughs] Then you step away, and it’s like, “Oh, it’s a human face.” It was a very strange way to work. I’ve never done anything like that. The idea was that to do this weekly strip where I was trying to tell this somewhat substantial story, I had to use every square inch that was available to me. I was squeezing panels in where they absolutely didn’t fit, and adding an extra word balloon here and there where I could, trying to get everything in there. To me it felt…not exactly claustrophobic—I was trying to at least give enough of a setting that you felt like you knew where you were—but it felt like there was a lot of density to those pages. The chance to do this book was a great opportunity to open up the space and give it breathing room, and establish the world, and not feel like you’re so cramped inside those tiny panels.

Many of those big spreads really do have this rhapsodic, spectacular impact when you reach them. Since they tend to come at important turning points in the narrative, they really took me aback and hit me, almost, emotionally. Which is kind of funny, considering how neurotic Marshall is about all his emotions.

[Laughs] Right. They’re really replacing time. I’m trying to use this space I’ve been giving to replace the time there was in between reading each of those strips. When I was writing the original strips, I was imagining a week in between the last panel of one strip and the first of the next. That’s not necessarily easy to recreate when you can’t force the reader to…“Can you please put down the book and wait one week and then read the next strip?” I felt like I had to work at it to give that space. Then you’re stuck having to depict something within the moment between two panels or two thoughts that may be absolutely contiguous. Somehow you have to divide that space and not interrupt the flow of the story. It was definitely challenging, and I went through a lot of different permutations. I cut up a lot of New York Times Magazines trying to figure out how to make it work. [Laughs] There’s actually several of them I don’t even have copies of anymore, because I had to cut up so many different versions and try out so many different things.

There’s also an emotional range to what’s accomplished in those spreads. The first thing I saw when I opened the book was the giant image of the “6:09 PM” digital clock readout.

[Laughs]

I found myself irritated by it! It was just oppressive, like when you look up at the clock when your alarm goes off and you’re like “Aw, Jesus.” But then there’s the spread of Marshall after Nathalie ends their date, and he’s isolated in darkness against these brightly colored, geometrically abstracted windows and lights, like he’s in a noir and this is a montage of him stumbling down the street drunk during his lost weekend. It made me laugh, just as parody. And then there’s the spread where he walks into a room and discovers an unpleasant scene, and it’s awkward and uncomfortable. An awful lot is accomplished with that one tool.

Yeah, well…thank you. [Laughs] It was challenging. To me, the hard part was restraining myself. I’m someone who likes to fill up every inch with stuff. I always feel guilty having a blank page. Some of those things…there’s one where I just had the sound effect of a car over two pages. I had all kinds of complicated stuff over that, and it didn’t quite work. I wanted what felt like a sound overlap in a film; that’s what I was trying to make the reader think of, where you hear the sound in a scene where it’s not quite appropriate and then you figure out what’s going on. You don’t know that he has this crappy car at that point. If you’re reading that having never looked at the book before or read the strip before, you wouldn’t have any idea what that sound effect is. But ultimately, I ended up cutting out all my other brilliant ideas and just sticking with this sound effect. That kind of thing is really hard for me to do. I don’t wanna ever look like I’m not doing the work that’s necessary. But that seemed to work much better than anything else.

A couple of years ago, Tom Spurgeon interviewed me about Craig Thompson’s book Blankets, and I said that the openness of the art style is what made it possible for many readers, especially those new to comics, to even contemplate reading a graphic novel of that length. By way of comparison I said that while Tom or I might flip out over a 600-page Dan Clowes book, for many other people the density of the art would make picking up a stack that size intimidating.

[Laughs] It would be fairly unbearable, I think. Although Jimmy Corrigan’s pretty close to that. That’s over 300 pages. Of course, no novice is going to pick that up and dive right into it. [Laughs] It takes some preparation to fully get that one.

That may have been the first alternative comic I really read, and I actually had to make diagrams for myself of how to follow the panels. Not that it’s not clear once you figure it out, but when you’ve only ever read comics with really straightforward layouts…

It’s very clear. He figured it all out beautifully. But it’s not something I would just give to my grandmother. [Laughs] “Here, read this!” You’d need to prepare them: “This may be a little difficult, but it’s worth it.”

So those big spreads make reading Mister Wonderful as a book have a more immersive, easy-to-read flow.

You haven’t gotten into this yet, but in the next few years, you’ll be reading many, many children’s books. That’s something you see occasionally in older children’s books: You’ll see the standard one big illustration per page with minimal text, and then all of a sudden there’ll be a few images on a page to further the story along. Maurice Sendak does it occasionally. Having read thousands of children’s books to my son, it seeped into my consciousness as I was working on this. That’s really where that came from. It’s one of those things: It seems against the rules to combine big single images with comics. For some reason, it seems like something you can’t do. Children’s books are always doing stuff that…they’re guys who don’t worry about that kind of stuff. They’re just trying to tell stories, and they’re not usually trained in storytelling and doing comics and things like that. I was inspired to see that stuff, especially when it was an abject failure, in a children’s book, because you started to think, “Now, how could this actually work?” You started to analyze it and figure out that there are potentials to these things that they’re doing.

I think those rules may be breaking down somewhat. For the longest time it seemed that there was a bias against making comics that way, and even looking at them.

It’s always interesting to think of what “doesn’t count” as comics. There’s lots of children’s books that really are comics and just aren’t included in the list of comics. [Laughs] Things like Edward Gorey, and a lot of the stuff that ran in National Lampoon…there’s stuff that somehow just doesn’t qualify. Yet.

I wonder if we’ll get there. There’s a bit of a movement right now toward one-panel criticism, where critics will write at length about an isolated image. And while I have nothing against Scott McCloud or Understanding Comics, you hear a lot fewer people using that: “Well, it’s not more than one image, so it’s not comics.”

That’s true. That was all the rage for a while, but it seems to have died down a little bit.

I also think it has to do with the Internet: It’s so easy to post a single image and talk about it, that people mix and match between comics and illustration, sequences and single images…people are more comfortable looking at it all with the same lens.

Oh yeah. And people like me and Peter Bagge and the Hernandez Brothers, we’re just like clip-art files for every guy on the Internet. [Laughs] We’ve done a panel for every subject you can think of, that’s appropriate for every point you’re trying to make.