My first “Grid” column for the new TCJ is the result of an experiment. I often find that when I have a negative reaction to a comic after a first reading, my judgment will change—frequently becoming more positive—after repeated re-readings.

My first “Grid” column for the new TCJ is the result of an experiment. I often find that when I have a negative reaction to a comic after a first reading, my judgment will change—frequently becoming more positive—after repeated re-readings.

Initially, I was unimpressed with “Bianca,” the first story in Moto Hagio’s celebrated A Drunken Dream and Other Stories. It seemed burdened by an over-reliance on tropes of sentimentality, both thematic and visual. So I decided to conduct an experiment: I would re-read the story (and no others in the collection) many times over the course of two weeks, to see if my reactions changed as my understanding developed. Then I would write up an analytical reading that reflected whatever insight I gained during these re-readings, regardless of whether or not I came to view “Bianca” as artistically successful. And after I finished, I would explore online writing about Hagio’s story to see if it affected my interpretation or judgment.

(The kind folks at Fantagraphics, who published A Drunken Dream, have put a PDF of “Bianca” online; feel free to read it before you read my commentary below.)

***

I first saw “Bianca” as a conventional sentimental tale, exploring such familiar themes as “the sanctity of childhood” and “the power of art.” And many online writers, regardless of their aesthetic evaluation of its merits, seemed to concur. Some found its sentimentality beautiful, others found it excessive, but all agreed it needed little explication. Had I read it only once or twice, I would have agreed, too. Yet re-readings revealed to me a far different, and far more compelling, surface and depth. Its sentimental idealization of the child is driven by what we could call a psychological “gothic revenge plot,” one that’s carefully formulated by Hagio against adult/older characters.

What’s most interesting to me is the way Hagio carefully sets up the story to appeal to child readers, in this case, young girls. The central tension that animates “Bianca” is found throughout children’s fiction, especially fairy tales: hostility toward authority figures, such as parents, other adults, and even older children or siblings. Within the logic of such tales, the young child is often an innocent under assault by the actions and beliefs of manipulative older characters. Such stories dramatize a wish-fulfillment fantasy for the reader, who is imaginatively allowed to punish an authority figure, occasionally even committing fantasy patricide or matricide. We see this in tales such as “Hansel and Gretel,” in which the evil step-mother, who had abandoned the title characters in the forest, mysteriously dies at the end, just in time to be deprived of wealth the children had taken from the witch, the step-mother’s doppelganger. Identifying strongly with the abused child characters, the reader (who likely resents authority figures who control her) might experience the death of both women as a fulfillment of a kind of revenge fantasy. In “Bianca” revenge is the real theme, enacted, as we will see, on Bianca’s cousin Clara.

Based upon the binary character groupings and symbolic oppositions, the story invites an allegorical reading. “Bianca” is a parable about childhood—more an abstract representation of concepts than a story with human characters. In this way it resembles children’s fables such as “The Ant and the Grasshopper," in which the anthropomorphic title characters stand for the opposing values of industry v. idleness. In “Bianca”, it is Bianca v. Everyone Else, which is to say The Natural Child v. The Cultured Adult.

As the counterpart to its hostility toward elders, “Bianca” expresses a kind of Neo-Platonic celebration of the young child. She is a pure soul, whose innate innocence reflects her divine origins. But as a child ages, the accretions of materiality—the trappings and productions of culture—drag her down. Wordsworth famously expressed the Neo-Platonic trajectory of an embodied soul’s degeneration in “Intimations of Immortality”: “Heaven lies about us in our infancy! Shades of the prison-house begin to close upon the growing” child. The prison-house of culture is the enemy of the young child and of the natural world she represents. Growing into an adult means being burdened by beliefs, rules, possessions, houses, clothing, etc. And most significant, adults deceive, lie, and withold:

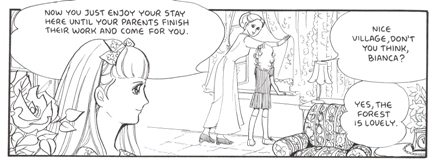

Many of the key elements of this parable are in play on its first page:

Bianca (on the left) has a hair style that’s more natural than Clara’s. (Bianca, which means “white” in Italian, encodes this natural purity.) The collar of her dress is rimmed with leaves, and what appears to be an epaulette is made from a branch of oak leaves. These unpretentious natural artifacts are almost a part of her; she is, as a character says, “almost a dryad,” a mythological wood nymph associated with oak trees. Clara, on the other hand, wears a symbol of culture in her hair: a bow. At first, the flowers she holds might appear to bond her, like Bianca, to the natural world. But that’s not how it works. The roses are held, not woven into her clothing like Bianca’s leaves, and most importantly, they are cultivated by her family, not grown naturally in the wild, and the petals are already falling off, an early sign of her decay. Like the roses she is often seen with, Clara has been domesticated: “I was raised in a country home with a rose garden.”

I’m not sure if Hagio intends this image to look sinister, but it does—a child oppressed by the prison house of culture:

In the title image, Bianca and Clara look to be the same age—they could be sisters, twins, or even the same person. But it becomes clear that readers must not confuse them. Clara tells us she is two years older:

In the title image, Bianca and Clara look to be the same age—they could be sisters, twins, or even the same person. But it becomes clear that readers must not confuse them. Clara tells us she is two years older:

And throughout we see that she is tainted by her alliance with adults (even though her mother treats her like a child). The older Clara, who fears nature and says she prefers to be inside, is the house,

and the younger Bianca is the forest:

Hagio creates a programmatic narrative in this way. Nearly every element reinforces its central premise: the older you get, the worse you act, and since there’s no way around aging, short of dying, you resent those who represent the horror you must become (older people are versions of the fairytale's ogre).

Hats play a key role in this premise. Symbolic of adult culture, they signal the adult’s desire to control and protect the child from things that really don’t threaten her, such as her body and nature.

When Bianca first arrives, she holds a hat but doesn’t wear it:

Clara, acting on behalf of adults (and saying something to Bianca that surely had been said to her) tells Bianca what's best for her:

In the story’s first narrative climax, Bianca goes to the woods and sheds the burdens of adult culture, namely most of her clothes. Hagio barely puts the hat on Bianca so we can have a dramatic scene of Bianca undressing, with nature's help:

In the story’s first narrative climax, Bianca goes to the woods and sheds the burdens of adult culture, namely most of her clothes. Hagio barely puts the hat on Bianca so we can have a dramatic scene of Bianca undressing, with nature's help:

The long panel showing Bianca’s feet offers a little tease of “the forbidden.” For a second, young readers can imagine the unthinkable: that Bianca is naked in the forest.

The long panel showing Bianca’s feet offers a little tease of “the forbidden.” For a second, young readers can imagine the unthinkable: that Bianca is naked in the forest.

Earlier, Clara had suggested the possibility that Bianca might engage in something forbidden while insulated from the adult gaze:

Free from surveillance, the young child can undertake acts of self-pleasure, which are condemned by those adults who want children to act in accord with their beliefs. Clara’s expression as she watches Bianca signifies the guilt she feels in seeing something “the authorities” don’t want her to witness: expressions of innocence and liberation that tacitly challenge the status quo.

Immediately after Clara sees Bianca in the forest, our dryad is confronted by an adult: her father. The visual/narrative transition reveals the connection between Clara and Bianca’s father, both of whom have violated Bianca’s innocence (Clara by mocking her, and her father by admitting the family is breaking up). So naturally, when violated, Bianca dies, as sentimental heroines so often do. In the story’s second climax, she runs into the forest and falls off a cliff, clutching the twigs that we saw in the title image. Death, then, is the only way to preserve her purity from the corrosive actions of elders. So, the first climax is Clara’s forbidden pleasure, and the second climax is her death. (Is the child being punished for a kind of metaphorical sexual act?)

On an interestingly composed page that employs many shading styles, Clara faints after learning of her cousin’s death. Hagio draws Clara’s mother as a series of swirling lines of different weights, and I assume this visual style mimics Clara’s impaired perception: we are “seeing” the mother through the eyes of the fainting girl. Yet these thick black lines give the mother a demonic aspect—and demonic is the deep nature of adults in Bianca’s world, who only appear to be friendly. Coming at a key moment, this visual approach amplifies my reading of the story’s intense antipathy to aging and adult culture:

***

All of the scenes I’ve discussed take place within “Bianca”’s embedded narrative, a sequence of events that occur when Clara is twelve years old. The story opens and closes with a narrative frame, in which Clara, now in her sixties, talks with a man about her paintings of Bianca. We could read the narrative frame as directing us to interpret the story as a künstlerroman (a story about the making of an artist), or as an endorsement of the sentimental artist’s need to be in touch with “the child within.” But the fantasy that “Bianca” plays out for the young reader might be something less sweet. Clara acted like an adult—she misunderstood and mistreated Bianca (and was even a co-conspirator in her death)—so she needs to suffer. And suffer she does. Hagio condemns her to feel perpetual guilt, to return via her art to the young child she hurt and whom her adult comrades killed. Bianca will haunt Clara as a ghost haunts its killer; she will be her primary artistic subject for life.

“Bianca," then, is a revenge fantasy: the wounded child (or wounded adult artist) desires that her oppressors will always remember the pain they caused: Clara's art is a sign, not of her love, but of Bianca’s “curse.” Nearly every time we see the adult Clara’s face, she looks depressed; is this an expression of her guilt? So Hagio and Bianca get their revenge. Bianca is sacrificed to affirm the fears of wounded child readers: adults really are out to get you.

Yet Clara’s paintings also seem false: every one idealizes Bianca, turning her into a cliché: a perfectly posed dancing ballerina. Clara caused her cousin considerable pain, but she avoids representing any pain in her art. Perhaps Clara learned nothing from her short time with Bianca. Decades later, she still sits in the house (its imprisoned gothic victim?), creating paintings that are a whitewash, that erase all signs of her guilt and complicity. Is Hagio aware that Clara’s art shows none of the complexities and none of the darkness that “Bianca” does? As an artist of the child psyche, Clara is a charlatan compared to Hagio.

***

Commentary on “Bianca”:

Katherine Dacey and many writers see “Bianca” as a “story about artistic expression,” in which the title character functions as a benign muse for Clara. She also says it’s “unabashedly Romantic,” and this is true—but it depends upon which kind of Romanticism you mean. At the surface, it’s Wordsworthian Neo-Platonism, but as a narrative about an artist driven by guilt and crime, it’s far more Byronic. When you paint the same person over and over, there must be something intense motivating you . . . My first reading aligned with Katherine’s, but later readings diverged, making the story more interesting than I first thought.

Seeing “Bianca” as a story about inspiration might obscure emotions just beneath its surface: the story’s sentimentalism hides its gothicism. When you idealize something so intensely—in this case the young female child—you tend to demonize anything that threatens it, namely everybody else. This is the logic of high sentimentalism and of the allegorical fable: The Ant does everything right, so the Grasshopper must be all wrong.

Joe McCulloch at Comics Comics writes that Hagio “is not a subtle worker—remember, some of this work is squarely aimed at children, rarely suggesting any poetic image or lingering character motivation that won’t eventually be spelled out via dialogue or narration.” I do think that “Bianca,” at least, buries some of its motivation and doesn’t really spell out the intensity of its hostility and gothic underpinnings. Joe notes that it’s written for children, and earlier I tried to unpack the ways it addresses the target audience’s concerns and desires: it’s interesting precisely because it’s aimed so intensely at the psyches of its readers.

Also at Comics Comics, Nicole Rudick notes that “mirrors also appear in “Bianca,” as an entrance to another world . . . particularly as a doorway between worlds, life and death . . . . Though the forest seems to claim her in death, implying a sinister aspect, Hagio never makes it clear which world is more humane—the forest that “kills” but in which she can behave as a free being, or the real world, where she is betrayed by her own family.” I see Clara’s idea that the forest kills or absorbs Bianca as a lie that disguises Clara’s role in Bianca’s death; what she says about the forest as a killer, she is really saying about herself and adults. Culture killed Bianca, not the forest. I think Hagio uses the forest as a straightforward symbol of Bianca’s natural innocence, which she sets against the house and village, the real sources of horror. If the forest does absorb her, it does so as the only way to keep her from a descent into adulthood, the beginnings of which we see in the judgmental young Clara.

When Bianca looks into the mirror, she looks into an adult-free utopia in which the soul always sees its eternal sunshine reflected back at it. To look in the mirror is to look backwards, a nostalgic glance to the soul’s original perfection. The mirror tells us, “The world would be a child’s paradise if only all of those old people would stop screwing it up.”

Noah Berlatsky: “Hagio’s style is delicate and pretty; layered on this delicate and pretty narrative, it just makes the whole thing so precious it’s hard not to gag."

“Bianca” now seems equally sentimental and sinister.

***

Well, the experiment’s results? As I mention above, the story became more interesting each time I reread it; it has many complexities that I initially overlooked. The nature of “Bianca”’s many oppositions (nature/culture, young/old, inside/outside, etc) and the ways they are dramatized with various images (such as hats and flowers) show the hand of a careful artist.

The story works hard to present the cartoonist as an adult who identifies so fully with children that she dis-identifies with all of her older characters. So in a strange way, “Bianca” seems pessimistic: despite its sentimental surfaces, it’s a bleak vision of a young reader’s future: what lies ahead is either death or moral corruption. But Hagio’s real concern is not with the future, but with feelings that may haunt a young reader’s present: “You are right to want to punish those who do not understand or appreciate you. I understand you.” It’s a sentimental-gothic fantasy that plays into a child’s paranoia about elders. And it’s fascinating.