First, a reminder that this column is exploring the comics of the Event. What is the Event? Read the introduction to get a broad outline of the project.

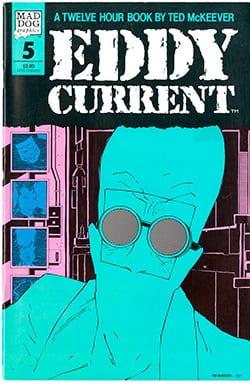

I never read Eddy Current (Mad Dog Graphic, 1987) when it first came out. It remains one of Ted McKeever’s best known creations. I read and liked his later Plastic Forks (Marvel/Epic, 1990), though I could not afford to complete that series, due to its then-astronomical cover price of $4.95! I’ll write about Plastic Forks another time. Like most comics from the Event, I became aware of Eddy Current secondhand: through bios, interviews, or the occasional ad I’d stumble on for the comic. I managed to acquire a few random issues over the years, but I never read them. As an inveterate collector, I always wait to complete a series before I read it. When I recently stumbled on the Eddy Current Trade Paperbacks (Atomeka, 2005) I jumped at the chance to read them.

I never read Eddy Current (Mad Dog Graphic, 1987) when it first came out. It remains one of Ted McKeever’s best known creations. I read and liked his later Plastic Forks (Marvel/Epic, 1990), though I could not afford to complete that series, due to its then-astronomical cover price of $4.95! I’ll write about Plastic Forks another time. Like most comics from the Event, I became aware of Eddy Current secondhand: through bios, interviews, or the occasional ad I’d stumble on for the comic. I managed to acquire a few random issues over the years, but I never read them. As an inveterate collector, I always wait to complete a series before I read it. When I recently stumbled on the Eddy Current Trade Paperbacks (Atomeka, 2005) I jumped at the chance to read them.

Gritty, deliberately grotesque, messy, and challenging; these days you don’t see comics like Eddy Current[1]. Many comics from the time of the Event had this quality. It was a deliberate distancing from the dominant styles established between the 50’s and 70’s, from the tight, abstract, dynamic pulp modernism (Kirby), and the elongated slickness of pulp neorealism (Neal Adams). In the 80’s, McKeever—along with his peers from that era, Kevin O’Neil, Bill Sienkiewicz, Kyle Baker, Howard Chaykin, Keith Giffen, and others—were developing new stylistic innovations that mapped closely to what was going on elsewhere in culture and art: postmodernism. Many comics of the Event share many qualities with this much maligned & misunderstood movement (whether intentionally or not). This pulp postmodernism (for lack of a better term) was still redolent of pulp and serialized entertainment, but it questioned all established comics hierarchies.

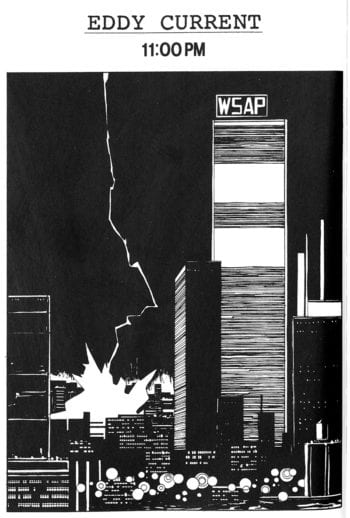

The story of Eddy Current takes place over the course of 12 hours. Each issue of the 12 issue mini-series corresponds to a single hour between 6 pm and 6 am. Since Eddy was serialized it still contains nods to pulp-style continuity. Each chapter/issue ends on a cliffhanger. But it is one of the many forerunners of the Graphic Novel that were published during the Event. It was conceived as a complete narrative, not intermeshed with any other continuities and it was intended to end after 12 issues. The characters would not live on forever in serialized publication. Of course there are other examples of mini-series that predate Eddy Current, but most were simply ‘spotlighting’ a character from some larger continuity. A complete self-contained narrative was still a relatively rare sight at that time. Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen predates Eddy by only a year. Even today, in the age of the Graphic Novel, McKeever is asked why he never wanted to draw continuing characters. The ongoing, never-ending, character franchise is still seen an an ideal for many. Any departure from that model is seen as anomalous.

The story of Eddy Current takes place over the course of 12 hours. Each issue of the 12 issue mini-series corresponds to a single hour between 6 pm and 6 am. Since Eddy was serialized it still contains nods to pulp-style continuity. Each chapter/issue ends on a cliffhanger. But it is one of the many forerunners of the Graphic Novel that were published during the Event. It was conceived as a complete narrative, not intermeshed with any other continuities and it was intended to end after 12 issues. The characters would not live on forever in serialized publication. Of course there are other examples of mini-series that predate Eddy Current, but most were simply ‘spotlighting’ a character from some larger continuity. A complete self-contained narrative was still a relatively rare sight at that time. Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen predates Eddy by only a year. Even today, in the age of the Graphic Novel, McKeever is asked why he never wanted to draw continuing characters. The ongoing, never-ending, character franchise is still seen an an ideal for many. Any departure from that model is seen as anomalous.

Eddy Current is a child of the black & white boom that swept the world of comics in the 80s to the mid 90s. Collectively, Black & White (B&W) boom comics (comics printed cheaply in black ink only; think Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Yummy Fur, Love & Rockets, Concrete, Cerebus, etc.) constitute a broad critique of what then constituted the mainstream of comics: the monthly Marvel & DC (the ‘big two’) titles. Looking back, many (the majority?) of titles in the B&W boom are actively critiquing, revising, parodying, weirding, extrapolating, intensifying the comics published by the big two. Very few titles veered into new narrative territory (Maus, Love & Rockets, Bone) to create a new space for themes and genres not previously explored by the big two. The B&W boom comics had largely a parasitical relationship with the big two publishers, and were enabled by the (then) new direct distribution model. The 80s as a whole could be characterized by superhero revisionism. Beginning with Alan Moore’s Miracleman, the success of the these new revisionist takes on the classic superhero inspired many imitators and innovators. Eddy, like many of the other B&W titles, was a revisionist superhero.

The story hits the ground running, introducing many of the main protagonists in fragmented and interwoven stories. The structure of the story has many hallmarks of postmodern storytelling: revisionism, the unreliable narrator, multiple narrators, fragmented storytelling, & metafiction.

The story hits the ground running, introducing many of the main protagonists in fragmented and interwoven stories. The structure of the story has many hallmarks of postmodern storytelling: revisionism, the unreliable narrator, multiple narrators, fragmented storytelling, & metafiction.

In the beginning, the comic has a clear parodic tone. Eddy becomes a hero by ordering his ‘Dynamic Fusion’ suit from the back of a comic book, making him a proto Flex Mentallo[2]. It’s a sly and meta way to indicate a 2nd generation hero—inspired by the classic bright, wholesome, modernist heroes of old—but born into our current degenerate postmodern world, which seems to no longer have use for the super-heroics of old. We learn that he’s inspired by The Amazing Broccoli, a ridiculous vaguely Frank Miller-esque, cancelled comic book. In a meta narrative moment, we get to read the issue that contains the ‘heroic’ death of the titular hero. Later, the comic book becomes holy scripture.

A number of characters remind us that heroes don’t exist anymore. A diner owner mourns the lack of real heroes in the world. But when Eddy shows up (a true hero in his own mind), half naked, in his vaguely bondage-gear-of-a-suit under a trench coat stolen (er borrowed) from a robbery victim wearing a pair of Converse (a reference to Mage by Matt Wagner?) he’s promptly kicked to the curb. He’s not welcome here in the ‘real world’. He’s an anachronism, an anomaly, an impossibility, or maybe he’s just crazy. In another scene, two criminals discuss heroes: “He as sure wasn’t helpin’ that bum outa the kindness of his heart.” “Shit. Those kinda people don’t exist anymore.” “Do They?” Right on cue, Eddy crashes (Frank Miller’s) Daredevil style through the window… only to be tossed out the same window a few panels later. Eddy’s super heroics are hapless and aimless, and yet he unerringly finds evil wherever he goes.

Eddy never abandons his mission however. He’s going to save the city, whether it wants to be saved or not. In that sense his mission is not very different from the villains of the book: a vague cabal of women (a stand in for the nanny state?) bent on broadcasting a signal that turns people into obedient, wholesome zombies (Marvel Zombies?). Both of their missions are to cleanse the world of ‘filth’ though that is ill-defined. Their leader is a gigantic morbidly obese woman (what was it about morbidly obese women villains around that time? I’m reminded of Ma Finn in Helfer & Baker’s The Shadow and Byrne’s Pink Pearl in Alpha Flight among others). I assume that these are probably vague references to Margaret Thatcher or Nancy Reagan who were both concerned with moral decline. Eddy teams up with a nun, a religious fanatic. She comes to believe he’s the second coming of Christ. They repeatedly talk about saving the world, “to rid this world of it’s cesspool antics. To teach anew the difference between right and wrong. To shed light where there is only darkness”. In the beginning this reads as parody, but over time it acquires an unexpected seriousness. The story becomes increasingly interrupted by biblical quotes, the tone begins to verge on millenarian, anticipating an apocalyptic ending. This is not unlike other comics from this era. Think of Cerebus, which started as a parody of Conan The Barbarian, and relatively quickly grew into something that took itself very seriously.

Eddy never abandons his mission however. He’s going to save the city, whether it wants to be saved or not. In that sense his mission is not very different from the villains of the book: a vague cabal of women (a stand in for the nanny state?) bent on broadcasting a signal that turns people into obedient, wholesome zombies (Marvel Zombies?). Both of their missions are to cleanse the world of ‘filth’ though that is ill-defined. Their leader is a gigantic morbidly obese woman (what was it about morbidly obese women villains around that time? I’m reminded of Ma Finn in Helfer & Baker’s The Shadow and Byrne’s Pink Pearl in Alpha Flight among others). I assume that these are probably vague references to Margaret Thatcher or Nancy Reagan who were both concerned with moral decline. Eddy teams up with a nun, a religious fanatic. She comes to believe he’s the second coming of Christ. They repeatedly talk about saving the world, “to rid this world of it’s cesspool antics. To teach anew the difference between right and wrong. To shed light where there is only darkness”. In the beginning this reads as parody, but over time it acquires an unexpected seriousness. The story becomes increasingly interrupted by biblical quotes, the tone begins to verge on millenarian, anticipating an apocalyptic ending. This is not unlike other comics from this era. Think of Cerebus, which started as a parody of Conan The Barbarian, and relatively quickly grew into something that took itself very seriously.

Both Eddy and the villainous women hate the state of the city. Eddy’s naive super heroics mirror the ones we are accustomed to: a costumed character physically beating the shit out of criminals. It deals with ‘bad guys’ not by fixing underlying structures that produce them, but by punishing them for the things they will inevitably do again and again. The women want to control our minds. They want to turn us into the perfect subjects: obedient, god fearing, and mindless. Both Eddy & the women despise the rabble, but their methods differ. Neither is willing to change the world.

Both Eddy and the villainous women hate the state of the city. Eddy’s naive super heroics mirror the ones we are accustomed to: a costumed character physically beating the shit out of criminals. It deals with ‘bad guys’ not by fixing underlying structures that produce them, but by punishing them for the things they will inevitably do again and again. The women want to control our minds. They want to turn us into the perfect subjects: obedient, god fearing, and mindless. Both Eddy & the women despise the rabble, but their methods differ. Neither is willing to change the world.

The deeper you proceed into the book, the more confident McKeever gets in his own skin. McKeever’s art rapidly changes from issue to issue. This might have not been as noticeable during original publication, since the reader would have to wait for at least a month between issues. But, collected in a single book, the differences really jump out. The first couple of issues are executed almost entirely with a clean line, but by issue 3 it morphs into blotchy, inky shadows with a marked heavy influence of Muñoz (one panel has a sign for Joe’s Garbage, a clear reference to Munoz & Sampayo’s Joe’s Garage). I’d be curious to know what else Ted was looking at back then. I detect homages to Frank Miller, Kyle Baker, Sienkiewicz, among others. But he absorbs these influences fairly quickly, and a style that is recognizably McKeever begins to shine about halfway through the story.

The superhero genre is an urban phenomenon. Most heroes require cities to function. The archetypes are: Superman, with his gleaming futuristic, hyper-modernist Metropolis, and Batman, who stalks a darkly gothic, spiked, crime-infested Gotham. The two heroes reflect the American attitude about cities. On the one hand, the city is Metropolis: a place where you can make it, re-invent yourself, and become a sophisticated cosmopolitan; a gleaming city on the hill full of hope and promise. But America is suspicious of cities, so Metropolis is also Gotham: a crime-ridden slum, where souls get lost and turn to crime, drugs and sex. It’s the antithesis of Smallville, the small town, a wholesome rural community; a place that doesn’t need heroes. That’s why Superman has to go to Metropolis. Only there can he help bring about the Utopian promise of cities. Wayne Manor is located outside of Gotham. It’s a suburban aristocratic mansion. This is where Batman returns to be himself: Bruce Wayne, an insane wealthy industrialist. Cities are sites of crime, danger, and political radicalism. The superhero is the avatar of that fear of the city… which can only be tamed by superhuman efforts.

The superhero genre is an urban phenomenon. Most heroes require cities to function. The archetypes are: Superman, with his gleaming futuristic, hyper-modernist Metropolis, and Batman, who stalks a darkly gothic, spiked, crime-infested Gotham. The two heroes reflect the American attitude about cities. On the one hand, the city is Metropolis: a place where you can make it, re-invent yourself, and become a sophisticated cosmopolitan; a gleaming city on the hill full of hope and promise. But America is suspicious of cities, so Metropolis is also Gotham: a crime-ridden slum, where souls get lost and turn to crime, drugs and sex. It’s the antithesis of Smallville, the small town, a wholesome rural community; a place that doesn’t need heroes. That’s why Superman has to go to Metropolis. Only there can he help bring about the Utopian promise of cities. Wayne Manor is located outside of Gotham. It’s a suburban aristocratic mansion. This is where Batman returns to be himself: Bruce Wayne, an insane wealthy industrialist. Cities are sites of crime, danger, and political radicalism. The superhero is the avatar of that fear of the city… which can only be tamed by superhuman efforts.

Cities also provide the critical infrastructure for super heroic acts. Leaping a tall building is a lot more impressive in Metropolis than in Smallville. The power and wealth of cities is matched by the destructive power of superheroes. They need the immense infrastructure of cities—skyscrapers, bridges, subways, sewers, highways jammed with cars, and countless blocks of curiously empty warehouses—to show off their powers. Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, and countless others, all live and ‘work’ in cities. How would Spider-Man get around without tall buildings to swing from?

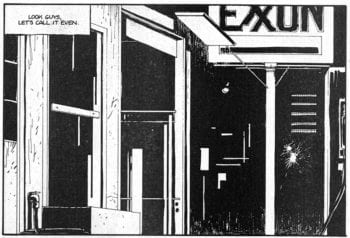

As required by superhero conventions, Eddy lives in a fictional city with a ridiculous name: Chad. The city resembles New York, especially the New York of the 80’s: grimy, with underfunded infrastructure, populated by lowlives and criminals, and loomed-over by gleaming towers of the ultra wealthy ruling elites. Chad is Metropolis and Gotham in one. This is where McKeever really shines. His keen eye really brings the city to life. He finds moments of stillness and quiet beauty in studied depictions of abandoned warehouses, gas stations, desolate alleys, and diners. Clean lines, attention to detail, exquisite framing. These moments make Eddy stand out from other comics of the Event. The anecdote told by Dave Gibbons in the introduction explains it. When Ted was visiting England, instead of taking pictures of local tourist attractions, his attention turned to other things: “In a little used children’s playground, some swings had their chains wrapped around their rusting support framework, whilst they were repaired and repainted. Ted took fifteen photos of them. In a corner next to them, some concrete had been broken up and fractured rubble lay across some mossy grass. He finished his roll on that. If there’d been any pictures left, the look of triumph and rupture on Ted’s face would’ve made a perfect memento for me.” This is researched rust, dirt, grime and dust. This tendency would be heightened to new levels in his future work.

As required by superhero conventions, Eddy lives in a fictional city with a ridiculous name: Chad. The city resembles New York, especially the New York of the 80’s: grimy, with underfunded infrastructure, populated by lowlives and criminals, and loomed-over by gleaming towers of the ultra wealthy ruling elites. Chad is Metropolis and Gotham in one. This is where McKeever really shines. His keen eye really brings the city to life. He finds moments of stillness and quiet beauty in studied depictions of abandoned warehouses, gas stations, desolate alleys, and diners. Clean lines, attention to detail, exquisite framing. These moments make Eddy stand out from other comics of the Event. The anecdote told by Dave Gibbons in the introduction explains it. When Ted was visiting England, instead of taking pictures of local tourist attractions, his attention turned to other things: “In a little used children’s playground, some swings had their chains wrapped around their rusting support framework, whilst they were repaired and repainted. Ted took fifteen photos of them. In a corner next to them, some concrete had been broken up and fractured rubble lay across some mossy grass. He finished his roll on that. If there’d been any pictures left, the look of triumph and rupture on Ted’s face would’ve made a perfect memento for me.” This is researched rust, dirt, grime and dust. This tendency would be heightened to new levels in his future work.

Most of the comics industry of the time worked on an assembly line model. Each comic had a separate writer, penciller, inker, letterer, colorist, and editor. Most of the comics of the Event (and at most other times) were produced that way. Eddy Current is different. McKeever is the sole author of Eddy Current. He wrote and drew everything. This was probably less by design, then by necessity since he was not an established talent at the time. Eventually McKeever would do work for the Big Two, and participate in the assembly line method of production, but this gives Eddy Current even more unique auteur-like flavor. The story and the art align seamlessly into a gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art. This is not to say comics Auteurs didn’t exist within the Big Two (and elsewhere), but it was a relatively rare occurrence.

Most of the comics industry of the time worked on an assembly line model. Each comic had a separate writer, penciller, inker, letterer, colorist, and editor. Most of the comics of the Event (and at most other times) were produced that way. Eddy Current is different. McKeever is the sole author of Eddy Current. He wrote and drew everything. This was probably less by design, then by necessity since he was not an established talent at the time. Eventually McKeever would do work for the Big Two, and participate in the assembly line method of production, but this gives Eddy Current even more unique auteur-like flavor. The story and the art align seamlessly into a gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art. This is not to say comics Auteurs didn’t exist within the Big Two (and elsewhere), but it was a relatively rare occurrence.

In the back of the first issue, there’s a short excerpt of an interview with McKeever, where he explains the origins of Eddy Current. He says, “why not put together a character who is psychotic but whose view is probably more realistic than the sane guys?” By saying that Eddy’s views are ‘more realistic,’ McKeever admits that heroes can be real, but to exist in our ‘real’ world they’d have to be insane. It’s a trope that has been mined endlessly since then, especially in Batman. Eddy Current is an interesting artifact from the Event. It prefigured many later developments, and proved its staying power by having been repeatedly re-issued. It makes me want to revisit other later McKeever comics.

Next: Batman: Son of the Demon by Mike W. Barr & Jerry Bingham

[1] We seem to be on the brink of a new mainstream. This mainstream is formulated and created mostly outside of the Marvel/DC umbrella. It exists across multiple genres and publishing houses. The inspiration is Manga, Anime, and modern American cartoons. It’s exemplified by clean lines (a kind of return to Ligne Claire of the TinTin era?), and that certain cartoony roundness of characters. It’s deployed across all genres. Superheroes, fantasy epics, existential teen age dramas, to anti-establishment zines, LGBTQ bildungsromans, etc. These days comics take more inspiration from the bubbly and clean lines of animation.

[2] Flex Mentallo was created by Grant Morrison in Doom Patrol 35 (08/1990). He becomes a hero by answering one of the most famous ads found in old comics: the Charles Atlas body building ad, in which a scrawny teenager trains to become “Hero of the Beach”.