By way of helping to celebrate Black History Month, we take a look at a couple of 30th year anniversaries. Robb Armstrong, it sez here in this promotional blurb, is the first Black cartoonist to have a comic strip with Black characters to run for 30 consecutive years. To honor the 30th anniversary of his comic strip JumpStart, Armstrong held a virtual book signing discussion for Syracuse University, where he created some of his first cartoons.

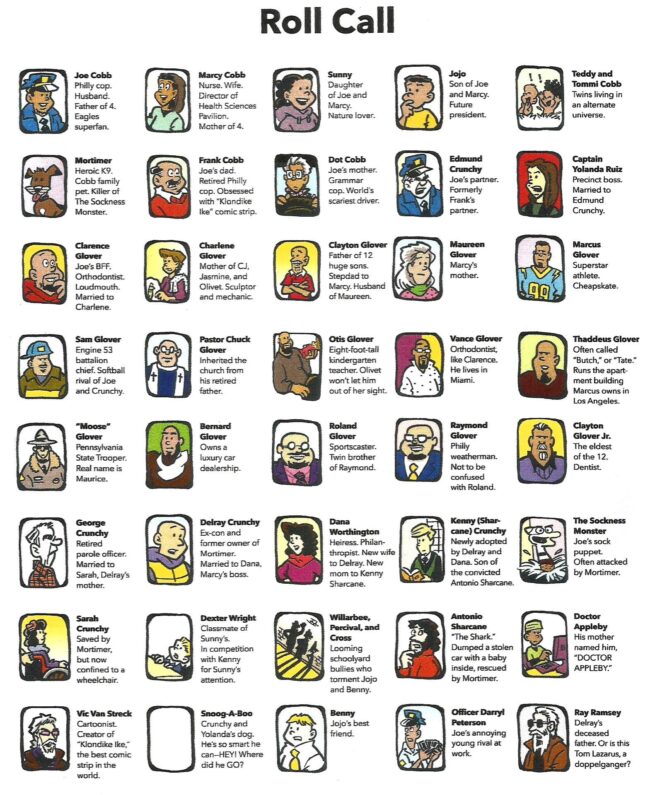

JumpStart tells the story of a Black family that is balancing their careers and raising children. The comic began in 40 newspapers with a “small cast” of characters. Now, it appears in over 300 newspapers and, with over 40 characters, one of largest casts for a comic strip.

But the publicity about JumpStart’s anniversary is arguable. Armstrong isn’t the first Black cartoonist to have his comic strip run for 30 consecutive years.

Morrie Turner’s Wee Pals ran from February 15, 1965 until 2014, the year Turner died (January 25). That’s 49 years. But maybe Wee Pals didn’t run 49 consecutive years. Maybe, I dunno, its run was interrupted for weeks or months somewhere along the line, and it didn’t run consecutively for 30 years.

But Turner had been doing Wee Pals for 24 years when Armstrong launched JumpStart on October 2, 1989. Armstrong tells of the thrill he experienced when he phoned Turner one time to get his advice on how to get syndicated—and that, of course, was before JumpStart started; so Turner, by simple autobiographical math, has enjoyed with his strip a longer run than Armstrong’s three decades.

But that’s beside the point. The point is that there’s more than one Black lives comic strip by a Black cartoonist.

And there’s yet another strip with a Black cast done by a Black cartoonist: Herb and Jamaal, by Stephen Bentley, syndicated now by Creators Syndicate, has been published daily since 1989. JumpStart also began in 1989, but Herb and Jamaal started a few months earlier, in July.

So Armstrong is scarcely the only Black cartoonist to have a comic strip run for 30 years. So far, we’ve named three strips by Black cartoonists about Black lives that have run for three decades or more. And we’re celebrating the anniversaries of two of them in this posting of Hare Tonic. We’ll start with Bentley.

Herb and Jamaal. Bentley’s strip centers on the eponymous friends who run a soul food restaurant together. It is inspired by Bentley’s experience at a high school reunion, and his desire to provide increased representation for Black people in comics. According to Bentley, interviewed by Shel Dorf in Cartoonist PROfiles No.90 (June 1991), "Some of the characters in Herb and Jamaal come partially from myself and people that I know, but the full story is just a fantasy..."

Born in Southern California in 1954, Bentley grew up in the South Central area of Los Angeles. In the late '60s, his family moved to Pasadena, where Stephen attended and graduated from John Muir High School in 1972. After high school, Bentley spent a short stint in the U.S. Navy, wherein, at Balboa Naval Hospital in 1972, he did a weekly one panel cartoon called Navy Life in the Drydock newspaper. After that, he attended Pasadena City College and, later, Rio Hondo College, majoring in Art, English and Fire Sciences.

Once in business as a commercial artist, Bentley worked for various advertising agencies, whose client list included the Los Angeles Dodgers, Wham-O Toys, the Playboy Channel and Universal Studios.

After attending a high-school reunion and re-establishing an old friendship in the late 1980s, Bentley was inspired to create the comic strip Herb and Jamaal.

Says Bentley: “Herb and Jamaal are two Black men who met in high school, and as they grew up, they developed a long-term friendship. Once they graduated from high school, they went their separate ways. Jamaal, a tremendous athlete in high school, continued his education at college and finally got into professional basketball.” His name, by the way, was inspired by another basketball great, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Asked once what Jamaal’s full name was, Bentley, one eye on that basketball player with three names, said: “Jamaal Jamaal Jamaal.”

While Jamaal was playing basketball, Herb went into the gasworks business.

Said Bentley: “After working for many years, Herb got married and began a family. After fifteen years, Herb and Jamaal met again at a highschool reunion [sound familiar?]. They renew their friendship ... they went back to the old neighborhood and found that things weren’t quite the same. ... The ice cream parlor where they used to hang out was no longer there. ... [It was] where their lives had evolved, where they had built their friendship and where they came up with their own personal philosophies. So they decided to re-open the ice cream parlor themselves.

“It was both nostalgia and business,” Bentley went on. “It’s a wonderful way for Jamaal, with his money from professional sports, to have a nice tax write-off.”

About five years into the run of the strip, Herb and Jamaal left the ice cream business and started running a soul food restaurant. Their business together is a tribute to lasting friendships and a reflection on a life well-lived.

“Jamaal is a bachelor,” Bentley said. “His professional life didn’t leave much time for him to be social and plant a firm foundation in his family life. It just wasn’t his desire at the time. He was footloose and fancy-free and needed the time to grow. Now he’s trying to pull together a social life, and it’s difficult for him.”

Another of the chief characters is Herb’s mother-in-law, who lives with Herb and his family.

“She is everything the typical mother-in-law might possibly be,” said Bentley, “—the mother-in-law from hell, so to speak. ... And when he got the ice cream parlor, Herb had to call his mother-in-law to take care of the kids sometimes. What she brings to the strip is her past, particularly her experiences as a Black woman and her role as a nurturer and as a foundation for the kids to learn about their background.”

AT THE TIME that Bentley was conjuring Herb and Jamaal, the newspaper industry was looking for comic strips with Black characters. The Detroit Free Press even circulated a letter to all comics creators asking if they knew anyone who could do such a strip—and also urging them to put Black characters into their own strips.

Through friendships in the Southern California Cartoonists Society, Bentley met Tom Forman and BenTempleton, creators of the Motley’s Crew strip. They were responding to the Free Press letter and trying to put together a comic strip by and about Blacks; they were looking for a Black cartoonist to draw it. They considered others, but settled on Bentley—perhaps because he already had a concept for the strip. Herb and Jamaal was launched July 7, 1989. Once the strip got going, Bentley did the writing as well as the drawing.

At first, Bentley wanted to use the strip to tell readers about the plight of being Black —“what the background was, what kind of problems were involved in Black relationships.”

But his syndicate— at the time, Tribune Media Services— didn’t agree. Said Bentley: “They said the humor was getting a little ‘dark.’ They said, ‘Let’s lighten it up. Let’s make it a little more humorous.”

Then a couple years into the strip’s run, one of the newspapers carrying the strip wanted to drop it because, they said, it wasn’t Black enough.

Bentley was mildly pissed. “Do they want a stereotype Black? What do they see as Black? I would like the characters to come across as, first of all, identifiable to any reader and, secondly, personalities that ring true to the Black reader.”

When he talked to the complaining editor, she said that she didn’t feel that they were Black characters, that the episodes that they were in were the kind that any character could be in, regardless of race.

“Well, this is true!” said Bentley.

It was exactly what he was aiming for.

“What kind of lives are Blacks going to get into?” he said. “They’re going to be doing the things that just about anyone else would do, Black, White or otherwise.

At first, Bentley didn’t see his characters as real, he told Dorf:

“I have to admit that when I first started the strip—and I think part of this had to do with the writing style we were using— these characters didn’t light up for me. I was struggling to build a relationship with them. Now, I know them. I come into this room, and I see these characters, and I say, ‘Oh. Where are they going today?’ I come up with an idea, and generally, if I just come up with an idea, they’ll take me to where I want to go. They usually will tell me what it is that they’re doing. They are real to me now. Very real.”

Although launched by Tribune Services thirty-one years ago, Herb and Jamaal is now distributed by Creators Syndicate and has been for some years.

Today, Bentley, who lives in Northern California, is a deacon in his local Episcopal Church (built in about 1850, it is the oldest church in the valley) and spends three days a week building and repairing bicycles with the underemployed. He has three grown children, two brought into the marriage by his second wife.

We conclude this section of our anniversary celebration with a glimpse of some of Bentley’s recent strips.

JumpStart. Turning to Rob Armstrong’s strip, we start with a look at an unusual autobiography.

Armstrong recounts his coming of age in Fearless: A Cartoonist’s Guide to Life (236 6x9-inch pages; text extensively illustrated with comic strips, cartoons, photos; 2016 Reader’s Digest Book, $24.99), which at times poses as a self-help how-to-draw book. The self-help is delivered in 20 drawing lessons, one at the start of each chapter of the memoir. Through sketching self-portraits or outdoor scenes and even practicing their lettering, readers (Armstrong hopes) can get in touch with their inner artist and embrace their mistakes.

At the end of each chapter, Armstrong presents found-on-Instagram feel-good quotes— "Pay attention," "Try every day to be better"— that urge the reader to move forward with joy.

For a quick run-down on Armstrong’s autobiographical life, we’re quoting (and occasionally enhancing) Elizabeth Wellington, Fashion Writer at philly.com; henceforth—:

At the heart of JumpStart is the perfectly nuclear Cobb family, helmed by Philly cop Joe and wife Marcy, an emergency-room nurse. Marcy and Joe have four children: nature-loving daughter Sunny, snarky son Jo-Jo, and a set of fraternal twins.

You might think the strip family is based upon Armstrong’s own life, and to some extent, that’s accurate. But over-all, the reality is that Armstrong's personal life is nothing at all like the pleasantly Technicolor world of his fictional Cobbs.

Apart from the drawing lessons and happy sloganeering, Fearless includes painful stories of the cartoonist's life. “Armstrong, 58, tells them with humor, aplomb, and at times an ego as big as Kanye West's, but not nearly as obnoxious,” saith Wellington.

We learn from the jump that things aren't easy for the young Robbin Armstrong, the last of five children coming up in West Philly. Their father has seemingly abandoned the family, and Robbin's mother, Dorothy, works tirelessly at a cleaners in Wynnefield. The family is always broke.

Armstrong likes to draw. His first attempts are awkward sketches of Fred Flintstone. And he looks up to his older, adventurous brother Billy.

In 1968, misfortune: the Market Street train closes its doors on 13-year-old Billy's leg, dragging him across the elevated train tracks. Billy later dies of his injuries.

The Armstrongs win a settlement from the city and rent a house in Wynnefield the next year. There, Dorothy becomes a respected community activist. That, however, does not end the bad times. On a walk home one summer night in 1969, brother Mark encounters police who, mistaking him for a criminal, beat his face to a pulp.

Dot Armstrong has had enough. She decides to try to save her last son through education, so she insists Armstrong apply to private school. He is eventually awarded a scholarship to the Shipley School in Bryn Mawr, becoming one of the first boys to attend the former all-girls school. (Later, Armstrong is presented with the Shipley School's Distinguished Alumni Award.)

More struggle. Armstrong must repeat the seventh grade, and his friends in Wynnefield start to ignore him because he's "too white to hang out with." He focuses on his art and realizes he wants to be a cartoonist.

Dorothy Armstrong dies of cancer during Armstrong's freshman year at Syracuse University. After graduating, he takes a job at a local advertising agency and draws his way into syndication with JumpStart. But he hardly had it made.

Life keeps knocking him. He marries, raises one child who has sickle cell anemia and another who has a club foot, watches close friends go to jail, lives above his means, and divorces his first wife. Through it all, Armstrong says, he drew and drew and never gave up.

In the mid-1990s, when he began speaking to children at Philadelphia schools and libraries, Armstrong realized he had a story to tell that went beyond the comics. After a few tv opportunities failed, he decided to write a book. He called it Fearless in memory of his mother.

"I wasn't the one out there slaying dragons," Armstrong says. "She was the one doing that . . . for us."

Armstrong hopes Fearless will inspire those who just can't seem to get it together no matter how hard they try. There is a light at the end of the tunnel, he says. And one day, who knows? Maybe his readers will be able to enjoy lives as idyllic and full of love as Marcy and Joe Cobb's.

THAT’S THE END of the Wellington review. She leaves out a few crucial matters. After his mother’s death, Armstrong was, in effect, “adopted” by two white couples; anticipating her own death, Armstrong’s mother had arranged with them to look after Rob. Together, they financed his college education, but they also supplied emotional support and guidance. Without them, Armstrong realizes, he would not have succeeded at all in any of his endeavors.

God helped, too. Armstrong recounts how, in his junior year at Syracuse University, he found God. Just in time. One of his supporting couples, the more religious pair, was on the verge of cutting him free. “They’d had quite enough of my arrogant behavior,” Armstrong notes. But his newly acquired spiritual rejuvenation re-established him with that couple as worthy of their attention and support.

Once he’d found Jesus, Armstrong gave up his wild campus capers and became a serious student. Apart from a couple pages reporting his conversion, Armstrong, blessedly, doesn’t discuss his religion. He just gets on with his narrative; probably a good choice.

The chapter that begins on page 123 describes the characters in JumpStart. Slightly over half the book has been devoted to Armstrong’s recital of his growing up; the remainder focuses on the comic strip and, to a greater extent, his marriage, his children, the collapse of the first marriage, and Armstrong’s secondary career as a motivational speaker.

About marriage, Armstrong says: “I was married at twenty-four, in 1986, just one year out of college. For me, this proved to be too early. Others may have different opinions, but I think no one should marry before thirty. Give yourself time to develop a bit more maturity before taking on life’s hardest and most important job—raising kids.”

I think this is a good book. I skipped over the self-help sections and the feel-good sloganeering. The rest of the book, the memoir, is engaging and disarming: Armstrong’s candor and reflections provide insight into his personality as well as the history of his strip.

ANOTHER BOOK, the more recently published (in 2020) On A Roll!: A JumpStart Treasury (208 8x11-inch pages, with color; Andrews McMeel paperback, $19.99), reviews the strip’s 30-year run by reprinting selected strips. Most of the strips are from the last decade although the book’s final, short (50-pages) section, “The Oldies,” goes back as far as the mid-1990s (before Joe grows a goatee).

The format prints 3 daily strips to a page, and it could have gone to 4 without sacrificing any of the quality of reproduction. Sunday strips in color get a whole page to themselves—again, more than generous enough allotment of space.

Taken as a whole, the strips explore family life and professional life (policing and nursing) rather than Black life. Not many of the strips belong in series, although the most engaging strips are from the series showing the Cobb twins in the womb, discussing their own development. They don’t acquire mouths until somewhat later, but they “talk” to each other regardless.

Perhaps the most helpful part of the book is the single page depiction of the 40-member cast. With that at my elbow, I can read today’s JumpStarts and understand what’s going on. I’ve included this page among the samples posted nearby, a few from the very earliest months of the run—1989 and 1990.