Sometimes an artist unleashes a character no-one saw coming. In 2013, that was Steffen Kverneland’s portrait of Norway's Edvard Munch. His graphic biography Munch shows “The Scream”’s creator to be a demonic party boy, an angry son and faithful nephew, a youthful nihilist and a tireless self-promoter.

Now, finally, you can make his acquaintance in English.

Its story zips around in time but its action is anchored in 1890s Berlin. There, Kverneland plunges you into a sexy, bohemian hothouse. Thanks to years of research, all the speech you hear is real. But best of all, the book is a visual fiesta. Munch steals from Munch, from portraiture, from punk, from early silent films and 19th century salon painting – not to mention a whole parade of isms: Impressionism, Cubism, Symbolism, Expressionism, Secessionism and more. Although its touch is light, this is art of erudition – made by a fan of Hogarth, Turner, Schiele, Caravaggio, Grosz, Matisse, Freud and Bacon.

Kverneland even writes himself into the tale. Here he's accompanied by a friend, cartoonist Lars Fiske. The pair pop up frequently to conduct a tipsy argument about how the Munch story should be told.

To find out how he pulled it off, I tracked Kverneland down in Oslo. There, well before Munch, he was famous for his series Classics Amputated (that title is a pun on the Norwegian version of Classics Illustrated). But… let's turn the history over to him.

Many new readers will meet you through the English version. Give us just a bit of background…

I come from Haugesund, a medium-small city on the west coast of Norway, and even before I could read I was into comics. Actually, I learned to read from Donald Duck. We also had Batman, Superman and Tarzan. Later, I got some French-Belgian comics in a weekly magazine: it had Tintin, Asterix, Lucky Luke, Comanche and Blueberry. Heavy Metal was also sold in the Haugesund kiosks and, thanks to that, I read about RAW in Lou Stathis’ column. Then, in my twenties, I moved to Oslo where I came across the anthology Read Yourself RAW.

RAW made everything seem possible in comics – there were no limits to how far you could go artistically. In my career, getting to know RAW was probably the single most important influence.

I started Classics Amputated back in the 1990s, when I was part of this Oslo literary milieu. It was mostly students and they started a highbrow literary magazine called Vagant. They asked me to do some illustrations and comics for that. At the time, I was into modernism, absurdism, Beckett and William Burroughs cut-ups. But discovering RAW had made an enormous impact on me.

Why was it such a turning point?

Until I discovered RAW, I tried to pursue three separate careers simultaneously. I was a fine artist making paintings and drawings, an editorial cartoonist doing political satire for the money, and a comics artist. I did both commercial work – like the Norwegian MAD – and my own experimental comics. Then it dawned on me that I could combine them all, in clever highbrow comics with radical graphics.

So I did some cut-ups from literary texts, mixed them up and drew some naked politicians uttering all these mashed up fragments, just subversive, anarchistic stuff like that. It was all very spontaneous, improvised and great fun to make. Later, I approached one of the big Norwegian newspapers and asked if they wanted to run my Classics Amputated series. They gave it a full page in the Sunday literary section.

This meant I had to work my ass off. But, with this great new audience, my work became increasingly refined, controlled, and less nonsensical. But I had a doctrine, a Dogme 95-style vow of not cheating with the quotations. They always had to be accurate.

My credo was that every fragment of text, no matter how trivial, could be turned into a comic – and I did a great variety. There were literary classics like Dante's Divine Comedy, which I set in Las Vegas and which was "played" by Frank Sinatra (as Dante), Dean Martin (as Virgil), Bettie Page (as Beatrice) and Elvis Presley (as God). I also did pulp romances, interviews with politicians and novels by contemporary Norwegian authors.

How did Classics Amputated lead you to Munch?

One day the editor gave me a copy of Rolf Stenersens’ 1946 Munch biography. It's this first-hand story of the young author’s meeting with the old painter-genius. It’s absolutely hilarious, but still sort of accurate – and it was perfect for me to pick out the funniest anecdotes and "amputate" them. From the very first panel I made, there was just no doubt: Munch would be perfect as a comic book character. This was during the late ‘90s. Then, in 2004, I illustrated a Munch biography for youth. He also made cameo appearances in some of my other work during the ‘90s. But, in terms of me making Munch, the Classics Amputated were central – both in choosing him as a character and in the rules to use proper quotations, credit all the sources, etc.

Your fellow artist Lars Fiske is also important. In the book, everything starts when you two hit the Munch Museum and start decrying the painter’s “myth”…

Since the mid-‘90s, Lars has been published by the same guys as me, so we would meet at parties. Later, we were both guests at a Norwegian comics festival. We hated it; the program was just too commercial and lowbrow for us. So we snuck off to drink beer and talk about art, music and comics. It was so much fun we began meeting up back in Oslo. Then, in 2002, I invited Lars to contribute some panels and a comic-essay for my book Slyngel (Rascal). It was a book of two autobiographical comics. One contained childhood memories, but the other one had a story about Fiske and me at the boring festival. That became the prototype for all the nerdy, gonzo docu-comics we’ve been making since.

In 2004, we released the collaboration Olaf G. It’s a graphic biography combined with a sort of gonzo travelogue. Its subject is the Norwegian master Olaf Gulbransson who, in 1902, was headhunted by the excellent German satire mag Simplicissimus. In search of his story, we went to Munich and Bavaria, then we wrote and drew the book together. That collaboration became really successful and it was published in Norway, Sweden and Germany. It was supposed to come out in English from Fantagraphics, too, until the tragic demise of Kim Thompson intervened.

Lars and I kept on working together. In 2006, we published the first volume of KANON – which was meant to be an annual book with new work from each of us. No. 1 had Lars’ first chapter from what became Herr Merz, his graphic biography of the German Dadaist Kurt Schwitters. My contribution was Munch’s first installment. We’ve put out five numbers of KANON but, over the last few years, Lars and I have worked more separately. However, we plan to revive it in the not-too-distant future.

Once you decided to tackle Munch, where did you begin?

One thing was for sure – I did not want to do a linear, strictly chronological, cribbed-to-death biography. That’s a terrible structure, probably the worst you can choose. It's highly predictable, it obliges you to include a ridiculous amount of boring transitional scenes – and it always ends with the death.

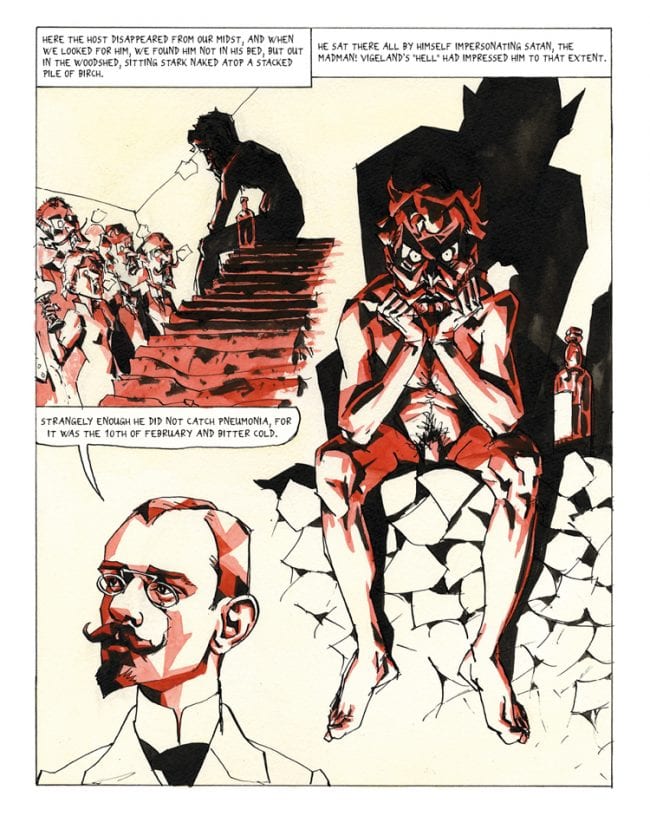

It’s puzzling to think of now but the key scene for me, this scene I was longing to draw, came from this story about a party at the villa of a poet, Richard Dehmel. It's where Munch’s buddy Stachu Prszybyszewsky finally goes nuts. He takes off all his clothes, goes out to the woodshed in the middle of a winter's night and starts posing as Satan (Munch, page 128-130). It was as if this fairly unknown anecdote, hilarious but also shocking, was simply beckoning me to make its comic adaptation. This was not part of the Myth of the Holy Genius Munch as we all knew it.

This Polish writer – a heavy drinker, a Satanist and a sexoholic – who was a close friend of Munch’s, he really intrigued me. So, of course, did Strindberg who I also looked forward to drawing and learning more about. Plus there were the women, like the mysterious Dagny Juel. She marries Przybyszewsky and gets shot to death at the age of 33. What was her story? I already knew that, during those feverish years in Berlin, Munch made practically all of his best-known works. That was when he became the Munch we know today.

So I decided to do a comic strictly about his Berlin years. That wouldn't take forever to research, write and draw, but it would still make a strong, unified composition – maybe a hundred pages, tops. The title was going to be something like “Munch – Berlin”. It would begin with Munch's arrival there and end with his departure; simple, logical and no-nonsense.

That was the initial plan?

Yeah, so I started buying all kinds of Munch books and reading everything about this relatively limited period of his life. I took notes of all the anecdotes and scenes, all that stuff I wanted to include. For me, the genesis has to be unpredictable and I have to be really engaged in the process – getting excited when I discover a good scene or anecdote I didn't know, and able to start drawing those things right away. Of course, this meant I sometimes had to redraw whole chapters, or at least scenes, because I would suddenly stumble across a source superior to the one I had used. Maybe it would be closer to the subject, or funnier, or more detailed.

The real problem was that Munch's life just didn't follow a strict chronology. He would jump around all over his “timeline”. His credo "I do not paint what I see but what I saw" says it all. When he was in his early thirties in Berlin, for instance, he was painting about his first love and losing his virginity. Which had happened ten years before, back in Norway. So I was forced to expand my story immensely.

But you stuck with historically accurate dialogue and descriptions?

But you stuck with historically accurate dialogue and descriptions?

I did, but it became increasingly harder to make this giant jigsaw puzzle fall into place. Often the story line would demand I get from A to B, yet I wouldn't have any sources to make the transition. I finally solved this problem with three storytelling "crutches". One, I would use radical jump cuts and then trust the reader to piece things together. Two, I employed what I started to call my “time-machine": the scenes where Munch lies in his bed, drinking or smoking and remembering exactly when and where I needed the story to go. My third "crutch" was introducing the meta-level in which Lars and I appear to comment, digress and drink – but where we also take the reader from one scene to the next. That way, things never become predictable. But I assure you it was hard; often, it felt really impossible.

Did you have a Munch-like Dark Night of the Soul?

When I was doing the final editing of the story, I lost faith in it. I was alone in my summer place over a few weeks’ time. I was sitting there shuffling printouts of all those pages that, during the six preceding years, had appeared in KANON as five neat chapters. “A piece of cake”, I was thinking, as I sipped my whisky and started trying to organize them into a book. Only: it just didn't work. Taken out of their context within each issue of KANON, the chapters seemed impossible to unite, they wouldn't speak with each other. They didn't connect. "Oh fuck", I started thinking, "There's no story in here. It's just a pile of unconnected scenes. I've wasted seven years of my life!"

This went on for a week or two and it was truly horrible. But, eventually, I was able to see some possibilities. If I made some new pages here, cut the entire sequence there, added a whole new intro in this place and a splash page in another one, moved certain scenes from the beginning to the end... and so on and so on until, at last, it kind of worked and made sense.

All your main characters – Strindberg, Munch, the Polish Satanist – are each portrayed in very singular styles. All of them resemble the real historical figures, but you also visualise their actual psychologies… especially with Strindberg. He's clearly both a poet and a total madman.

When I designed the different characters, I would gather as many visual sources as I could: paintings, drawings and, hopefully, lots of photos. I would print them out, spread them around me, then start sketching. First I would sketch realistically, explore and get to know their faces. Then, gradually, I would try and exaggerate distinguishing features, break them down into simple, almost abstract – but, hopefully, easy to recognize – comic characters.

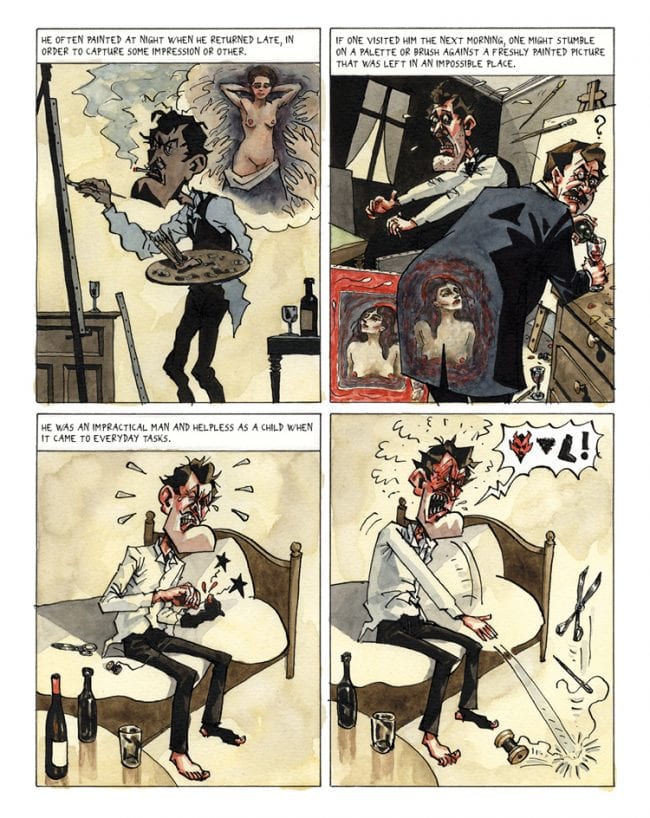

That process was very important because often I needed that level of abstraction. With Strindberg, for instance – and also with Munch himself – I had to go as far as I could. Because each of them had such an expressive character and temperament, and Strindberg… well, he was sometimes just plain crazy. When he went ballistic, I could be consciously inspired by expressionistic Cubism, adding a few dashes of emotional abstraction via the likes of Ralph Steadman and Peter Bagge.

My main problems came from minor, less famous, characters, for whom there were few or maybe no photos. In one case, all I had was a single caricature. I couldn't even know if it was actually good or bad, it was just all I had. There was the same problem with their hangout in Berlin, the notorious Schwarzen Ferkel bar. All the written sources have to say about its interior is that the walls were filled with shelves – and they were crammed with bottles of booze. I just had to invent it.

Colors and styles I use in different ways for various reasons. For instance to indicate different points in time, as when full color indicates the "present", i.e. Berlin during the 1890s. Brown paper signifies flashbacks to childhood and youth; the black-and-white "photo-realism" historic documentation, like when Munch's older self remembers his younger days. The sketchy line drawings on white paper are hasty notes, as if they were “made in the field” when me and Lars are out and about.

This freedom to change styles didn't exist in comics during the ‘80s. It wasn't even an option, nobody did it because it would be wrong, a “mistake”. The most important thing a comic artist had was his personal style. In terms of this, my first epiphanies came from Stray Toasters and Elektra Assassin by Bill Sienkiewicz. In those, he seemed to change styles just on a whim or whenever he felt like it. And it worked! If the script was tight, I realized, clearly you could draw with any style you wanted. The reader would still connect; it was no obstacle to the story. This apparently total freedom deeply impressed me, and I’ve been taking the same liberties ever since.

With Munch, did you have to stay flexible until the end?

Yes because reality never ceases to surprise you. Unlike fiction, it’s totally unpredictable. What surprised me most – although it was a blessing – was Munch's own character. The myth about him is this black hole of a man, a suffering, haunted genius, starving, misunderstood, half-mad and always sad. But there were many more sides to him; just like the rest of mankind, he was a lot more complex.

For instance, he was known by friends to be a very funny guy who told jokes, wrote them hilarious letters and like to draw crude caricatures of himself on picture postcards. He was always surrounded by both friends and supporters. Munch had an enormous amount of self-confidence, too; when it came to promoting himself, he was really aggressive and inventive.

Of course, none of this was news to the academics and experts. But in general, with films, documentaries, novels, articles and the like, the same old myth is still being hammered home. I was actually interviewed in a recent documentary, Let the Scream be Heard, by Indian filmmaker Dheeraj Akolkar. He was and still is a big fan of my book – and yet he edited out everything I said that contradicted all the old myths. I was furious! But it just shows, those myths will always be there.

Graphic bios are really trendy – but a lot are just flat failures. Munch is something totally different. For one thing, it really shows how creativity works, the roles played by accident, friendships and chance discoveries.

To me, the great advantage of comics is their ability, when they’re done right, to show instead of tell. This applies especially to graphic bios of artists. Comic artists often know a lot about how paintings and drawings are conceptualized and made, so they can often visualize the process instead of merely trying to somehow “describe” it.

However I think there are three major traps. One is indulging in the myth: the starving, lonely, misunderstood, tragic genius. Two is the predictable, repetitive recounting of the artist's life as seen from a great distance. Just transmitting information is, in terms of a graphic novel, really extremely boring. Three is adding irrelevant and banal "artistic" elements, most often elements of magic realism, to your story. It shows you don't trust the project and never should have started it.

Kim Thompson would be over the moon having Munch in English. Almost every other language beat us to the punch!

Being published in English was my ultimate ambition or maybe I should say “hope”. I think it's the wet dream of every comic artist. An English translation is your key to the rest of the world, you can really send it to any publisher anywhere. This is where the loss of Kim is enormous.

I hope no one forgets what he accomplished and all the bridges he built.

Even before it (even) came out in Norway, Kim told me he was going to publish Munch. He wanted to translate it himself, so we were having email discussions about that. For instance, I suggested that my own Norwegian dialect become a Southern drawl. But Kim felt that would make me sound too stupid. Instead, he decided to give Lars this kind of posh 'Queen's English' voice. He was such a great guy, it's so terribly sad he died.

In 2011, you know, he was a special guest at the Oslo Comix Expo. There, from the stage, he announced that Fanta was going to publish Olaf G. Which, of course, was thrilling for Lars and me to hear. Afterwards, we all ended up in a little neighborhood bar. Just Kim and his wife, Lars and his wife, me and Liv. We had a really great time. All of us were fans of the HBO series "Deadwood" and the weird eloquence of that character Al Swearengen. So we ended up all using the foulest language we could manage… We all appreciated a little break from comics-as-business.

Munch by Steffen Kverneland is now available in English from SelfMade Hero