Comics historian, author, editor and curator Maurice C. Horn passed away on December 30, 2022, at the age of 91.

Horn studied at the Faculté de droit de Paris and earned his law degree in 1952. After graduation, he worked as a clerk for a Parisian law firm. Unfulfilled by legal work, he collaborated with writer Claude Moliterni under the joint pen names Karl von Kraft and Franck Sauvage, writing genre novels and scripts for radio plays. In the late 1950s, on advice from a literary agent, Horn emigrated to the United States. Although his English language skills were not sufficient to earn him gainful employment as a television writer, he was offered a job as an escort interpreter with the Department of State. He continued to work for the US government in this capacity until 1974, and served the United Nations as a freelance interpreter through the 1990s.

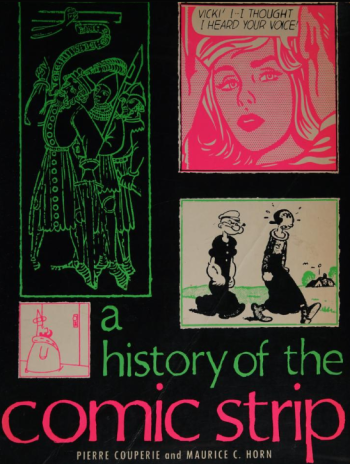

He would often return to France, and in the 1960s he joined two groups, the Club des bandes dessinées and SOCERLID (Société civile d'études et de recherches des littératures dessinées), that treated comics with a seriousness accorded to the established arts. It was during this era that Horn assisted curators Pierre Couperie and Moloterni with a major exhibition for the Musée des Arts décoratifs in Paris: "Bande dessinée et figuration narrative", which was on display from April 7 through June 12, 1967. An English translation of the exhibition catalog was released by Crown Publishers in 1968 under the title A History of the Comic Strip, with Horn and Couperie as the cover-credited authors among several contributors. This book “helped inspire a new wave of comic art exhibits in museums and university galleries in the 1970s,” Munson tells The Comics Journal. “In some ways, I think that book was more important than [Horn’s subsequent] encyclopedia, because it was the first book to provide curators with an intellectual analysis of comic art and how it works.”

Couperie had conceived of the original book and written five of its twelve chapters, as well as most of the book’s chapter notes. Horn’s contributions included chapters on American comic strips and global developments, as well as, crucially, securing an American publishing deal. “His cachet, minimal except as a duck in a rather small pond of comics scholarship, was being this European–an automatic patina to culturally provincial Americans–didact,” recalls Rick Marschall, who was just beginning his own career as a comics historian when he first met Horn at a convention.

Horn’s subsequent curatorial efforts included "AAARGH! A Celebration of Comics", on display at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London from late December 1970 through early February 1971, and "75 Years of the Comics", which was featured at the New York Cultural Center in the fall of 1971. A book accompaniment to the latter exhibition, also titled 75 Years of the Comics (Boston Book & Art, 1971), was notable, observes Janocha, as “a 'first attempt' at reprinting full page Sunday treatments, before Bill Blackbeard's Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics effort a few years later.”

“The group of scholars and analysts represented by Couperie, Horn, and Moliterni, were the pioneers of a movement,” says Marschall. “Contemporaneous manifestations cherishing the ‘Ninth Art’ appeared like puffball mushrooms on a dewy lawn, in conferences, magazines, university studies, and conventions.”

Charismatic and enthusiastic, Horn became a familiar figure to comics enthusiasts on both sides of the Atlantic in the late 1960s and early 1970s. He was immortalized as the suave and sophisticated recurring character M’sieu Toute–the sound effect “toot” was an obvious play on the name “Horn” to those in the know–in Milton Caniff’s comic strip Steve Canyon in the summer of 1968.

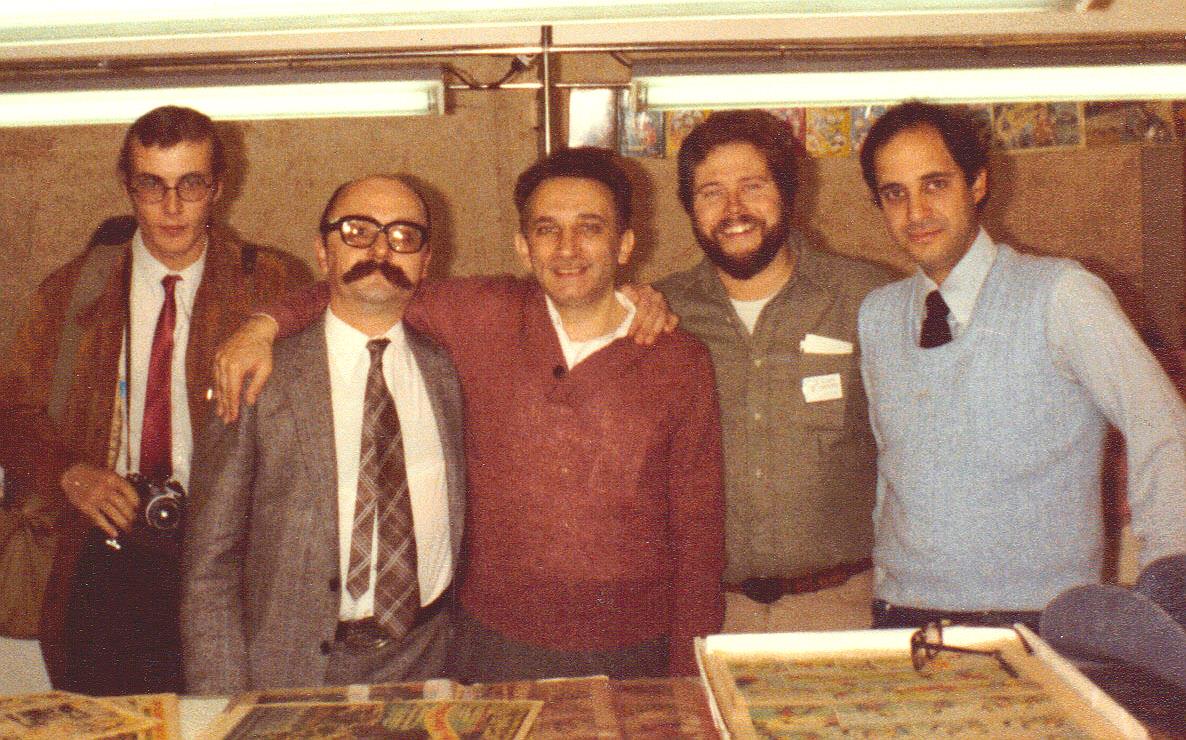

Horn was present at many of the earliest comic book conventions in the United States, and was highly regarded by fans, retailers, and comics professionals due to his status as a comics historian and published author. The outgoing intellectual become a focal point of several aspects of the comics world, and enjoyed facilitating introductions between his friends and colleagues.

In 1971, at Phil Seuling’s New York Comic Art Convention, it was Horn who introduced underground cartoonist Denis Kitchen to The Spirit creator–and early proponent of comics as legitimate art–Will Eisner, with whom Kitchen would collaborate extensively over the years. “I was a delirious fan on the floor of the hotel’s dealer area, riffing through white boxes, when a man with a French accent interrupted me, asking if I was Denis Kitchen,” recalls the artist. “He introduced himself as Maurice Horn. I recognized Maurice's name immediately because he had co-curated a groundbreaking exhibit of comic art in Paris a few years earlier, and I had the catalog. In those days there were very, very few books about comics. My catalog was well-thumbed.

“Without digressing, he went right to the point. ‘Mr. Will Eisner would like to meet you,’ he said. Of course I also knew of the legendary Will Eisner but there was no reason whatsoever that he would want to meet a young cartoonist/publisher from Milwaukee. I assured Maurice that he must be mistaken, but he insisted, and asked that I follow him. He proceeded to take me to Will Eisner’s hotel suite. After introducing us, Maurice exited, and, aside from some scattered correspondence, I don’t recall that we ever met in person again.”

But Horn also locked horns with members of the cartooning community. Marschall recalls the first of these feuds originating during the "75 Years" exhibition. “He fell out with the Newspaper Comics Council, which in essence was a lightweight trade organization with few scholarly pretensions or even ambitions,” says Marschall. “I recall that the Comics Council had expected to be the sponsor and organizer of the exhibition, and its rejection earned Maurice the enmity of Alfred Andriola of the Comics Council–and therefore the latter’s intimate friend Milt Caniff–as well as with Jack Tippit of the National Cartoonists Society; and many, many others in the field.

“There was a widespread perception that [Horn] had hijacked the exhibition project, but it would have been akin to a class project at a neighborhood mall if the Comic Council had been in charge. I do know, however, that some cartoonists who cooperated–a number of underground and alternative cartoonists whose first ‘establishment’ recognition was afforded by the show–were, sadly, needlessly offended in various ways and had problems with, for instance, the return of their artwork.”

“Some people are bridge-builders by nature,” Marschall continues. “Maurice was a congenital bridge-burner.”

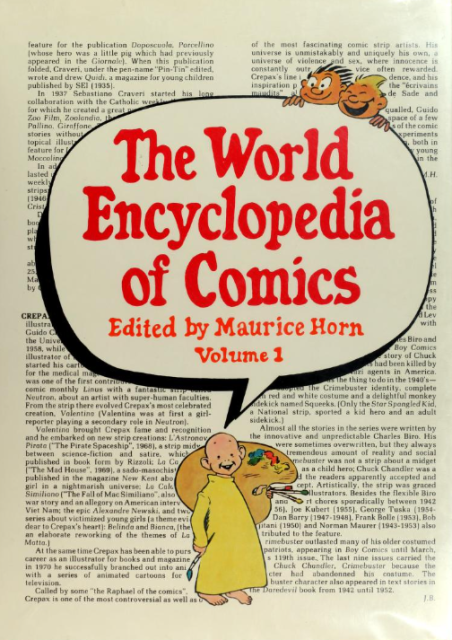

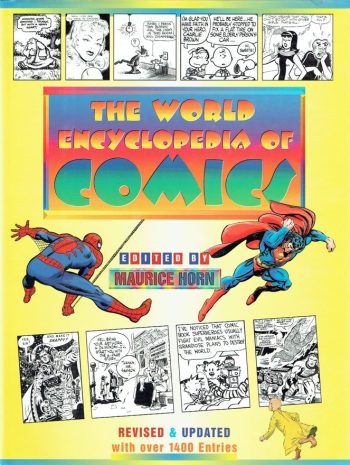

Upon its publication in 1976, The World Encyclopedia of Comics was heralded as a foundational work and a cornerstone of all future comics scholarship. “When I was in my teens, and interested in the history of comics, you could make a shelf about three feet long of historical books,” says International Journal of Comic Art editor Michael Rhode, “and Horn took up about a foot of that.”

Author and publisher Malcolm Whyte cites Horn as an inspiration for his decision to found San Francisco’s Cartoon Art Museum, less than a decade after the publication of The World Encyclopedia of Comics. “As a beginning original cartoon art collector I found Maurice Horn’s Encyclopedias, one for cartoons, the other for comics, invaluable,” says Whyte. “They opened my eyes to the breadth of the art form. It was so exciting. There was nothing like it at the time.”

Cartoonist and historian Brian Walker, who served as chief curator at the Museum of Cartoon Art in Greenwich, Connecticut, when his father Mort Walker established that institution in 1974, appreciated Horn’s efforts in comics scholarship at a time when few were making the effort to document the history of the art form. “His encyclopedias were an invaluable resource for me when I first started doing exhibits at the Museum of Cartoon Art back in the 1970s,” says Walker. “There weren’t many other books to use for research. I always had a problem with them, however, since they were called ‘encyclopedias’ but many of the entries were highly opinionated.”

Horn had, in fact, encouraged his writing team, which included American historian Bill Blackbeard, to editorialize as they saw fit. Many of the older writers leapt at the opportunity to air their long-held opinions, while the younger contributors, including Mark Evanier and Rick Marschall, tended to strive for more fact-based encyclopedia entries. Marschall notes that his own copy of the Encyclopedia bears an inscription from Evanier that proclaims, “you and I are oases of accuracy in a sea of errata.”

The contributors that Horn recruited represented a mix of both experienced historians and promising newcomers, including Manuel Auad, Gianni Bono, Joe Brancatelli, Wolfgang Fuchs, Luis Gasca, Denis Gifford, Peter Harris, Orvy Jundis, Hisao Kato, Ervin Rustemagić and John T. Ryan. “To be chosen for a pioneer work destined for libraries and the bookshelves of aficionados was an honor, even at 10 dollars per entry, paid by checks we were required to endorse while signing away all subsequent rights,” says Marschall. “Maurice adjured to be critical, claiming ‘in the manner of Diderot, father of the concept of the Encyclopedia.’”

Later scholars questioned the accuracy of many entries in The World Encyclopedia of Comics, which required an unprecedented amount of research into comics history at a time when very little had been formally collected or documented. One of the most glaring errors in the first edition is in the entry for George Herriman’s classic comic strip Krazy Kat, mistakenly illustrated by a parody comic by underground cartoonist Bobby London. “Back then, many mistakes were made,” says retailer and historian Robert Beerbohm. “Most were well-intentioned, but [Horn] had too little to go on at the time.”

Horn gave his contributors a loose rein, recalls Marschall, and credits him with never demanding that they adopt his own pugnacious approach. “He would suggest commentary, and his own entries were filled with derogatory references to drawing styles; the quality of work, for instance, by successors of creators, perceptions of originality…. Ironically, in his own machete-swinging entries and choices of illustrations, Maurice committed many errors that laid him open to criticism. The Encyclopedia was, and remains, a valuable resource but, as I am suggesting, could have borne the subtitle Horn’s Compendium of Unforced Errors.”

The success of The World Encyclopedia of Comics was a watershed moment in the study and preservation of comics history, a fact acknowledged by even Horn’s critics. “I grew up on these books and respected them as treasures of massive and obscure information, even if at times imperfect,” says Janocha.

“Horn and Couperie got guys like Bill Blackbeard and Rick Marschall up off their ass!” says Beerbohm. “As Americans they thought they needed to reclaim our heritage from the French. This was at a time when jazz and comic strips were being recognized as the two truly unique American art forms.”

“The arguments over what was proper factual history were legendary in their time,” continues Beerbohm. “It caused Americans to formalize and dig out the actual history, a quest that the next generations are still continuing. For many, it began with A History of the Comic Strip.”

Subsequent editions of The World Encyclopedia of Comics, which was published regularly in hardcover through the late 1990s, included corrections, revisions, and additional entries and contributors. Not content to rest on his laurels, Horn edited The World Encyclopedia of Cartoons in 1980 - an attempt to create a comprehensive history of animation as a companion volume to his comics history. “I just pulled my copy of The World Encyclopedia of Cartoons and found myself stunned by the volume and scope of what Horn brought together as editor of the pioneering compilation of material,” observes editor and historian Maggie Thompson. “Have you opened it recently and imagined what it would have taken to pull it together in 1980?”

The success of the encyclopedias gave Horn the financial stability and clout to write about other comics-related topics. Books such as Comics of the American West (Winchester Press, 1977), Women in the Comics (Chelsea House, 1977), Burne Hogarth's The Golden Age of Tarzan, 1939-1942 (Chelsea House, 1977), and Sex in the Comics (Chelsea House, 1985) proved commercially successful enough to warrant multiple printings and new editions over the course of several decades, but none had the lasting impact of The World Encyclopedia of Comics. Marshall laments that too many of Horn’s later works “essentially were rehashes of his pioneering books, brought out in multi-volume editions to enhance library-sale profits, or justified by anniversaries of the business.”

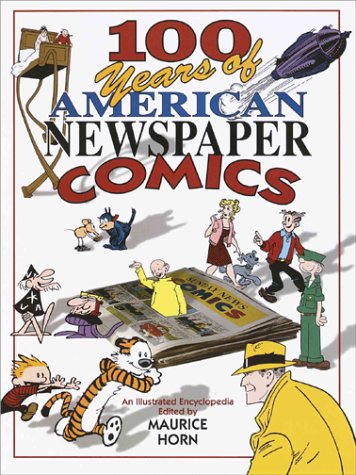

100 Years of American Newspaper Comics was Horn’s final new book, although he continued to collect, study and discuss comics art and history for the rest of his life, and often discussed his wish list for future books and other projects. Interviewed by Kim Munson for her 2016 International Journal of Comic Art piece, he talks about wanting to write a history of European cartoonists, updating research he did for Heavy Metal magazine in the early 1980s.

Even Horn’s critics acknowledge his indelible contributions to the study and appreciation of comics as an art form. “Horn's books weren't without detractors, but by God, they showed a young man in New Jersey that there was a lot to the world of comics that was worth seeking out,” says Michael Rhode. “And the bigger books at least were everywhere in the 1970s so you didn't have to work to seek them out. I lost my copies of them in a basement flood a few years back, and hadn't looked at them for years before that, but I still feel a tug of nostalgia when I think of them and have to stop myself from ordering replacements. The world of comics scholarship got big, but I'm not sure it's bigger than Horn and his fellow French enthusiasts hoped and expected.”

Horn was a complex individual, with one historian offering up the concise summary of his legacy as “pioneering but problematic.” Maybe that was exactly the kind of person that comics, dismissed by academics and even many in the field as a subject unworthy of respect, needed when Horn entered–and, in many ways, created–the study of comics history and comics appreciation. “Perhaps Maurice Horn was born with a chip on his shoulder, or was simply a rebel with an independent streak. In any event a large ego was never hidden, nor in doubt,” says Marschall. “In a brief period he alienated the National Cartoonists Society, the Comics Council, major syndicates, and myriad cartoonists, and never betrayed regrets. In fact, he often started conversations or meals with an almost enthusiastic question, ‘what are my enemies saying about me?’ It seemed anything but paranoiac. The joy he took in alienating, even betraying and losing friends surely hurt his professional advancement, and affects his legacy.”

The legacy he does leave, however complicated, paved the way for historians, curators and aficionados; modern comics scholarship owes a great debt to Horn and his passion for the art form. “Possibly Maurice traveled in higher circles and was better respected during the years before I came across him, when he seemed to me oddly to be someone 'passed over,' and relegated to the fringe of the industry and only semi-welcomed,” Bill Janocha says. “I feel he should truly be remembered for his trailblazing work as a historian and collector.”

* * *

Special thanks to Kim Munson and Rick Marschall for providing biographical information and their personal recollections of Maurice Horn.

* * *