If you were reading Japanese comics in translation around the turn of the millennium, and you are now logged onto this site without a gun to your head, there is a high likelihood that you were obsessed at some point with Bakune Young. First published stateside in VIZ's beloved 'mature readers' manga magazine Pulp in 1999, and collected in three softcover volumes in 2001 and 2002, Bakune Young is the sort of comic one never forgets: beginning with a man going mad in a pachinko parlor and ending with a lamentation of the faith of people in nations and leaders, it is a work of intense, undulating cartoon sensation animated by extremes of anger and sadness, despite being hugely funny. Writing in The Comics Journal #247 (Oct. '02), MVP manga critic Bill Randall described the series as a work of social conscience portraying the grotesqueries of conflict - that it does this while retaining the check-your-breath verve of the best action comics is an achievement not lost on Randall, myself, or anybody who's read it.

The author, Toyokazu Matsunaga, was never published in translation again. In fact, by 2005, he had stopped publishing in Japan as well. But he had not stopped drawing - every so often, for much of the '10s, you would be reminded online that 'the Bakune Young guy' was serializing a massive webcomic, PaperaQ, completely separate from the professional manga apparatus. And then, during the pandemic, I learned that not only had Matsunaga finished this project—totaling over 3,000 pages of new comics—but purportedly made arrangements with an independent translator to prepare a pay-what-you-want English edition. It also turned out I was familiar with the work of the translator in question: Carlo Vanstiphout, a Belgian writer on cult film, who had participated in the wild west of unauthorized seinen manga 'scanlations' in the '00s. This, however, was an official, one-on-one endeavor, with the majority of the financial proceeds going to Matsunaga.

PaperaQ is a formidable thing - what begins as the sad story of a young boy with an infectious mutating disease becomes a decades-spanning saga of imperial ambitions, genetic revenge, and living lonely among others online. In the interests of further exploring this unique saga, I asked Vanstiphout to write something about Matsunaga's work and the origins of the PaperaQ translation project. In addition, TCJ has solicited the first-ever public comment from Matsunaga on the English-language project; many thanks to A. Degen for his translation.

-Joe McCulloch, Editor

* * *

In a sense Toyokazu Matsunaga and I go way back. I’ve never officially met the guy, but the internet is a funny place. I first learned about him roughly 15 years ago via a little thing called scanlations, and this group I used to volunteer for called Mangascreener where the goal was to only ever do “ethical” scanlations. As soon as something got picked up by an English-language publisher, it was quittin’ time and on to the next project that the world wasn’t ready for yet. Examples of said projects that later got picked up for official release: 20th Century Boys, Children of the Sea, Beck, Ciguatera, Goodnight Punpun, Sexy Voice & Robo, Vinland Saga, Bokurano: Ours, Love Roma, Nijigahara Holograph, Me & the Devil Blues, etc. It was a pretty cool outfit, and for a very long time my main gateway to the elusive world of atypical manga. It taught me a lot when other outlets were failing me by catering to the lowest common denominator.

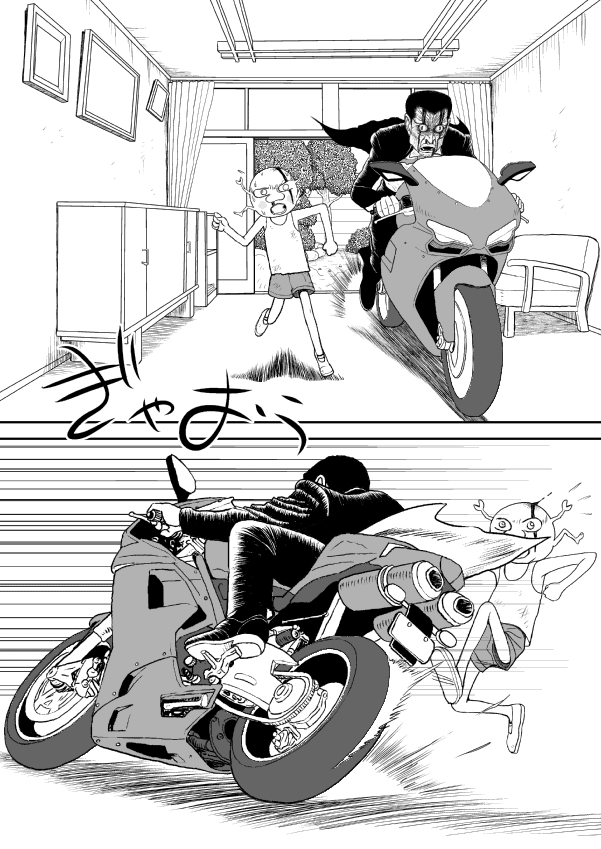

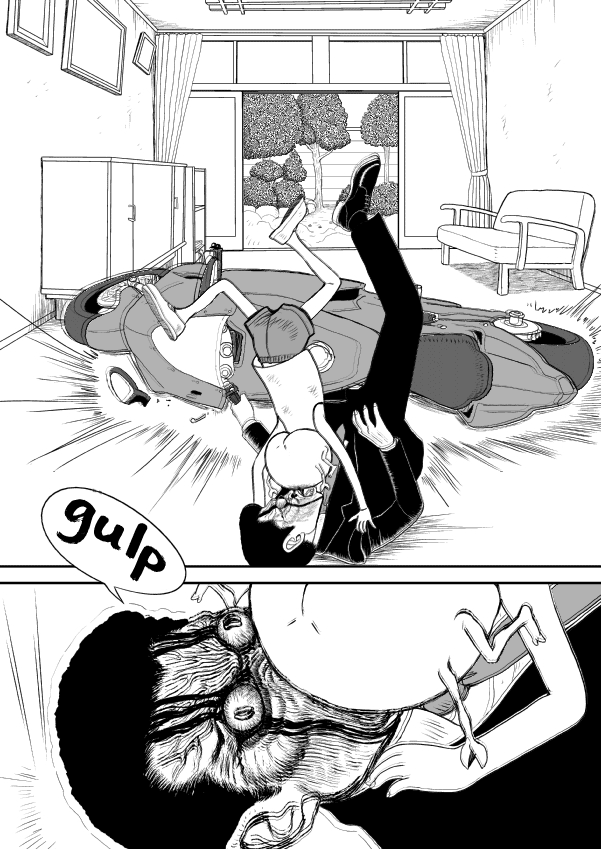

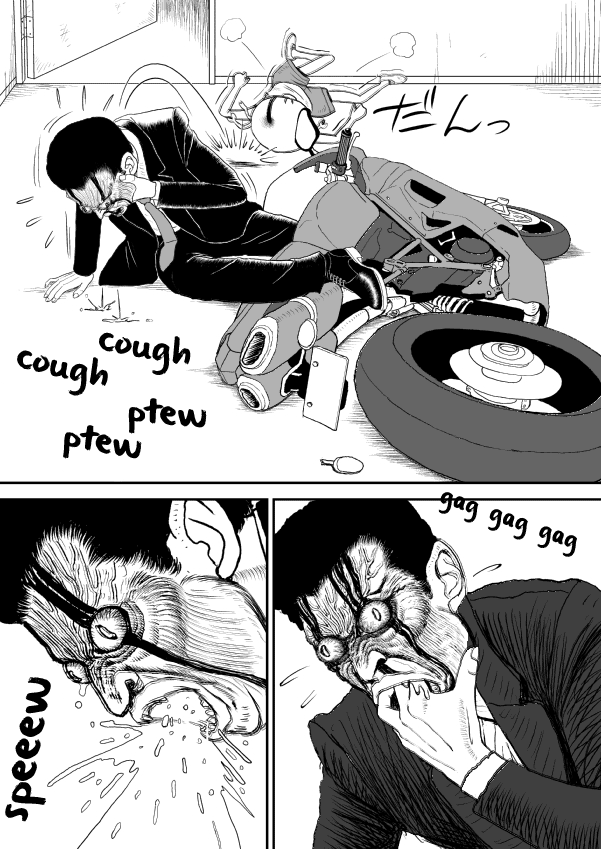

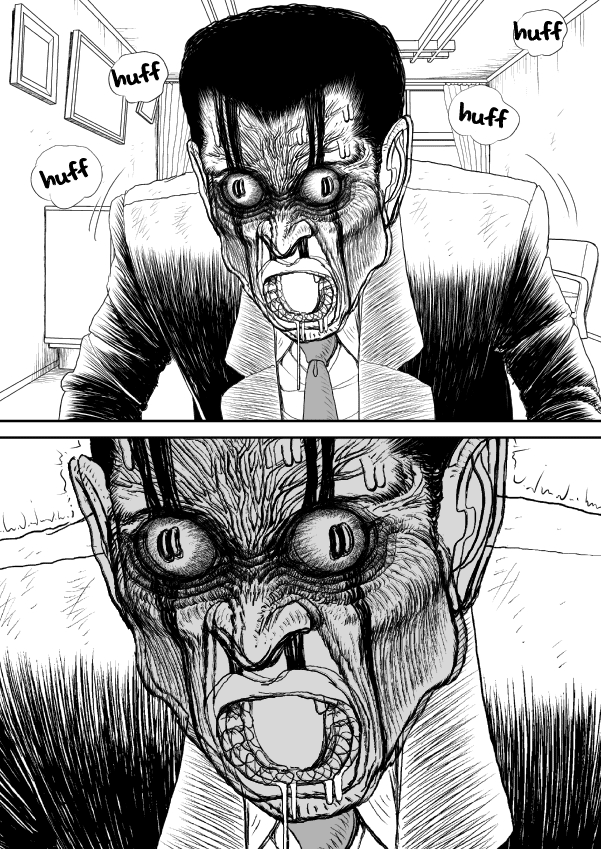

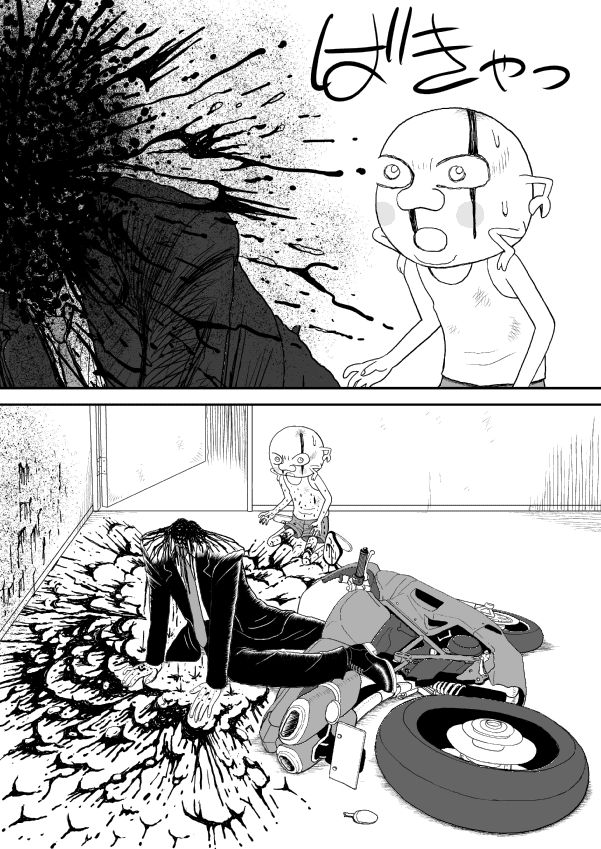

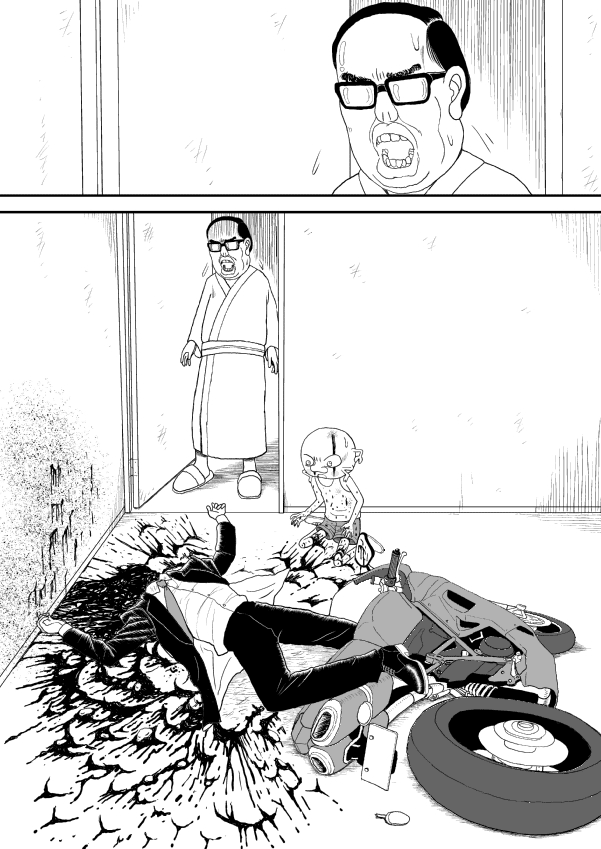

I’m not claiming I was instantly hip to the unique and obscure world of Toyokazu Matsunaga, but coming into contact with a fan-translation of Ryūgūden (2002-05), and later finding out about VIZ’s release of Bakune Young (1993-97, 2000) definitely helped shape and subvert my sensibilities both as a reader and an artist. The one thing that hits you when you read one of Matsunaga’s works is the fact it’s drawn in a way that is almost defiantly un-manga-esque. Bakune Young looks more like something you’d find in a moldy copy of Heavy Metal your dad forgot he had tucked away underneath a box of Steely Dan CDs in the basement: grotesque, impossibly detailed, and animated in a way that emphasizes character. It’s so bursting at the seams with commitment that the mere experience of reading it can be exhausting if you don’t know what you’re getting yourself into. It’s anarchy in a world where tropes and shortcuts are the norm. It’s the highway out of your comfort zone.

Explosive, and disinterested in playing to the crowd. Punk in a world where that barely means anything anymore. My impression is that Matsunaga’s failure to turn his talent into a prosperous career is, at the same time, why his fans talk with such reverence about Bakune Young. You want to share your love for this freak existence, but who other than people who draw will understand what it takes to create certain images? Who has the time for stories that aren’t regurgitations, other than people who spend most of their time in the confines of their own mind, pushing those membranes back far enough to allow the mental space to read some sweet bullshit about two teenaged brothers wearing bunnysuits who hop on a dick-shaped train and battle fish mutants through time and space in an underwater brothel? It’s lowbrow by choice, done to perfection.

I’ve been in touch with Matsunaga ever since he hesitantly started self-publishing a webcomic, PaperaQ, in 2011, and with my (at the time) adequate knowledge of Japanese, I recall reaching out to him via social media to tell him how big of a fan I was, and that I looked forward to his return to manga serialization. It had been five years since he wrapped up Ryūgūden in Shōgakukan’s “too cool for a long life” IKKI magazine, and he confided in me that the lack of sales had made a lasting dent in his confidence. For context: IKKI was never intended to compete in the big leagues, and thus it had historically low circulation numbers. So I can’t imagine it being a case of having misguided expectations. It wasn’t exactly a place where you’d become the next Akira Toriyama, and no one needed it to be.

The world, and Japan in particular, isn’t necessarily open to people who are too individualistic. Be confronted with that reality enough times, and anyone will start to crack a little. There’s also the reality of what it means to be a manga artist on a deadline, and for the first time you can see Matsunaga succumbing to using visual shortcuts with Ryūgūden. Backgrounds are sparse, and character models are recycled wherever justifiable. Yet while there’s a sense of compromise, it doesn’t feel compromised because Matsunaga is an experienced artist who knows how to use empty spaces to his advantage. At once he’s figured out a way to dose his efforts, while at the same time allowing the narrative and the visuals to breathe more. Sadly, the gravy train never showed up for Ryūgūden and Matsunaga.

A large part of creating is not over-thinking things, and PaperaQ is a rear window into the mind of an author who is slowly regaining his self-confidence as he finds meaning in not just the process, but also by extension the story he wants to tell. When I asked Matsunaga what the title "PaperaQ" stood for, he said it was "just some made up word from my childhood that got stuck in my head." It's an answer that embodies how much of an unguided missile it may seem at first, which will no doubt turn most people off for good. We currently live in a world of serialized prestige dramas, where consumers feel entitled to 'purpose' and larger-than-life conflict. Everything has to be 'grounded' in human emotions, and have the highest production values, or we skip to the next thing with a push of the button. And all of that, with the obvious exception of said production values, is present in PaperaQ. Tragic deaths, political intrigue, generational conflict, tales of redemption, songs about makin' a dook in the river. It's all there baby!!!

But hey, if you don't need any convincing then don't worry, he's still the same artist you already love. Sharp, original, not one to romanticize. While his works have always existed on the fringe of commercial publication, more than ever PaperaQ was Matsunaga's very own personal playground, where he got to try out all of the ideas he's toyed with in this lifetime. While Matsunaga's inner child tends to come out in the form of crude jokes and over-the-top violence, his adult brain, which is capable of critical thinking, presents us with themes of karmic retribution, and how the only way to break a cycle of injustice is forgiveness. Visually it might not be as exhaustive as a Bakune Young, and it lacks the whimsy of a Ryūgūden, but thematically it is as clear-eyed and generous as anything he's ever put out.

Toyokazu Matsunaga concluded PaperaQ in the Fall of 2020 after nine years of diligently putting out 30-some-odd pages every first of the month. No assistants nor revenue to support him, but no one looking over his shoulder to limit his artistic freedom either. I’m not sure how many commercial manga you’ll be able find that not only reference but use Japan’s past war crimes and notorious Unit 731 as a major plot point, but it was a first for me. It's not exactly the kind of material they teach you at school, so as someone who's interested in both the good, the bad, and the ugly of Japan, I'm grateful that some manga about a disease that makes your head explode with crab limbs also taught me a thing or two about a thing or two. It's nice when it's not JUST empty calories.

My own life and journey to Japanese fluency took some turns during the past 10 years as well. For a long time I was forced to drop the ball that is an author-sanctioned (and as close as you’ll ever get to an official) English version of PaperaQ. But sometimes you just need some distance from the things you love to remember. And when I saw that PaperaQ had wrapped up in the Fall of 2020 at 110 chapters, I said to myself “What the hell, it’s the pandemic and I know way more Japanese now. Let’s put this baby to rest.” I’ve now posted translations of the entire series online where you can grab 'em all for a “pay-what-you-want” scheme in 10-14 chapter increments, with the bulk of the proceeds going towards Matsunaga in support of his unrecognized talent, and the rest towards myself as an agreed-upon translator fee. The first part, which is also considered the “childhood arc” of PaperaQ, is entirely free to download. So please give it a try and take it from me: what seems like something that was drawn up on a whim quickly evolves into an epic of historic proportions. No hyperbole. Okay, maybe some hyperbole.

* * *

TCJ contacted Toyokazu Matsunaga for additional comment. This was his reply:

The English version of [PaperaQ] began thanks to the kindness of Carlo Vanstiphout. I had been serializing the comic on my own personal site, and Carlo found it and got in touch with me. For someone like myself, who is not affiliated at present with any publisher, who had been making the comic for no monetary compensation, to have the ability for my work to be in English and therefore reach the world was very encouraging.