Comic book adaptations of movies weren’t new in 1984—Marvel Comics had already had success with its Star Wars series, as well as comic versions of Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and Krull (1983).

But the comic book adaptation of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi epic Dune, brought to the screen by David Lynch (not yet famous for Twin Peaks and Blue Velvet), was special.

“There was so much hype for Dune,” remembers Tom DeFalco, then executive editor at Marvel. “We were hoping that it was going to be another Star Wars.”

The Dune adaptation also marked a turning point for artist Bill Sienkiewicz, who was finishing up his run on Moon Knight and was beginning his seminal, career-defining run on New Mutants. In Dune, Sienkiewicz would embrace a mixture of Ralph Steadman-like gonzo inks while also exploring geometric shapes inspired by American painter Richard Diebenkorn.

It was a rare adaptation that was as bonkers as the movie, and an artistic triumph on its own—that seldom-achieved successful crossover of artistic vision, commerce and dynamic storytelling. But it wasn’t a particularly easy project to publish, given tight deadlines, tensions with the studio and a script that wasn’t fully baked.

Three editions of the project were published, the original Marvel Comics Super Special: Dune #36, a three-issue mini-series and, finally, a full-color pocket-sized paperback. On the eve of director Denis Villeneuve’s new film version of Dune, TCJ revisits the first comic book adaptation to tackle Herbert’s epic story about interstellar politics, ecology, power and the foundations of religion.

Here, the creative team talks about this strange, unforgettable adaptation of a troubled movie and a beloved book.

* * *

Ralph Macchio, writer: I was a big fan of the Dune books, and I definitely wanted to write it. I bought the paperback back in 1965 when it came out, and I still have it. And I just fell in love with the Dune universe. There was just something about it...the fascinating world that you lose yourself in, like the Marvel Universe or Middle Earth.

Bill Sienkiewicz, artist: Macchio was going to be the writer, and he was a really good friend of mine. And so why don’t we do it together? And so that was really kind of how it started. It was really a passion project...which is an odd thing to say about a movie adaptation.

Tom DeFalco, executive editor: Dune was a property that a number of us liked, because we’d read the books and were excited about the movie.

Ralph Macchio, writer: There was a lot of buzz about doing adaptations because these were usually movies that we thought were going to be big, maybe blockbusters—and Marvel being a part of it—that was fantastic. There was another Marvel adaptation of a movie called Meteor, which starred Sean Connery. Gene Colan drew it, and I wrote it. It was about a meteor that just happened to hit New York City. We had a choice between doing that or Alien, and Marvel picked Meteor because of the visual idea. No one knew that Alien would be the incredible hit that it was, and that it would spawn a franchise that exists to this day.

Bill Sienkiewicz, artist: I’d seen a lot of other movie adaptations, and kind of a thankless gig because you’re really being relegated to the level of a Happy Meal — one more cog in the merchandising to carry the film. You’re dealing with rights, and with likenesses and everything else. Sometimes I feel like what comics can offer...a lot of that creativity is actually overlooked.

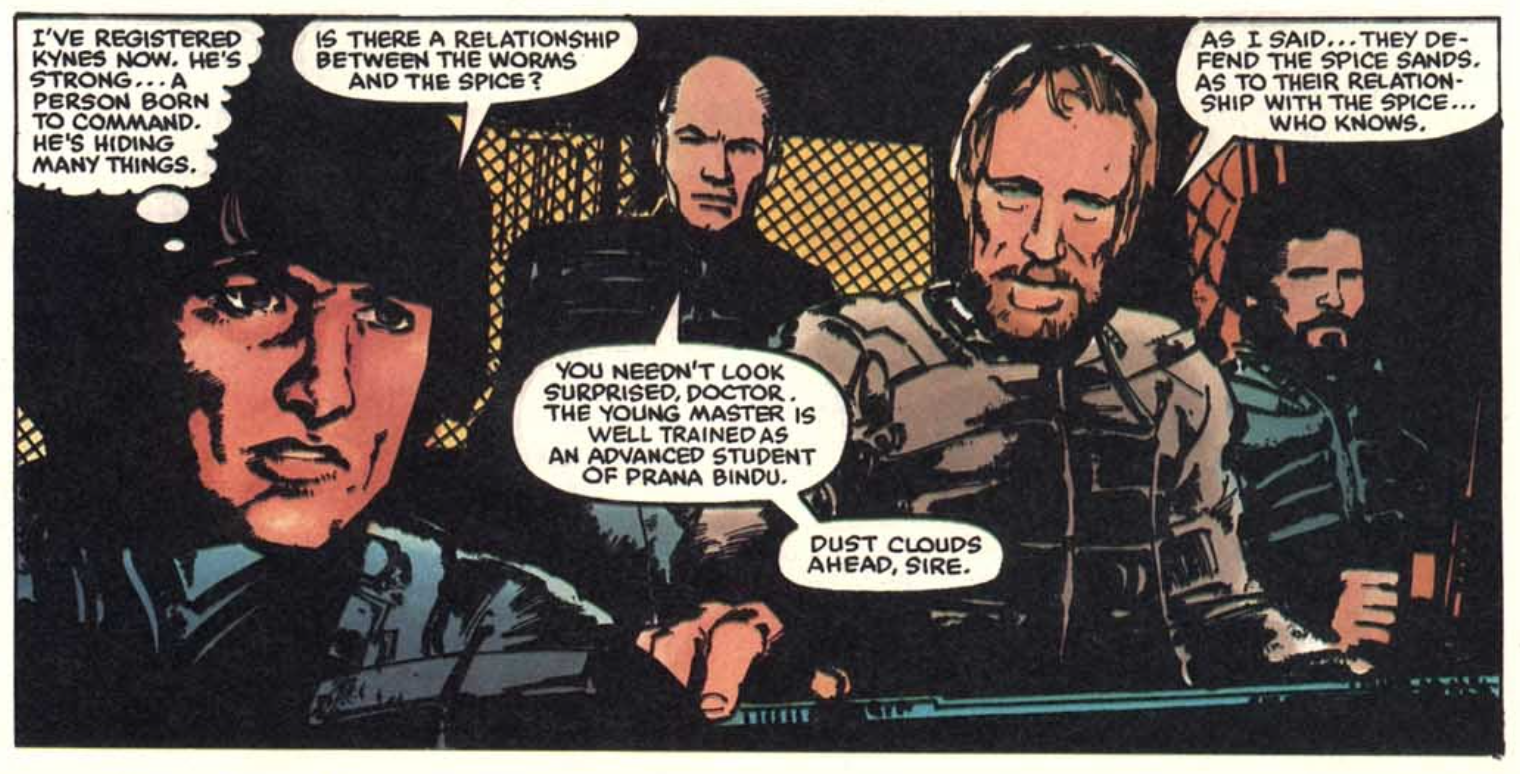

Bob Budiansky, editor: We’re doing this months in advance of the movie premiering. Movie studios really don’t want to release advance copies of their movies to anybody. They want to keep it top secret. But usually movie stills are more than enough and if you’re working with a good movie studio, they’ll be very cooperative. They’ll get you anything you need—if you need a shot of this character in the scene, they’ll find it, you know?

Bill Sienkiewicz, artist: I flew out to California and met with some PR people. The movie was in production, but we needed to get a head start on it. So they gave us a bunch of color Xeroxes. They gave some images of the actors. But it was a constant struggle to keep getting the references we needed. And that’s always kind of a thankless task.

Christie Scheele, colorist for the Super Special: Bill Sienkiewicz was really my favorite comics artist from when I first arrived. And I was coming from a fine art background. I was always interested in people who were working in a more stylized way. Not everybody loved his work, and especially among the old guard, but I just loved it immediately. He was one of the few people in comics who I could have a conversation with, artist to artist, because the other ones—they just didn’t connect with the kind of fine art issues that were going through my brain. So when I was assigned to the project it was really just amazing. It was not only working on top of Bill Sienkiewicz, but it was also working in full-color on top of Bill Sienkiewicz, so that was what really stands out in my memory as a project that I really enjoyed.

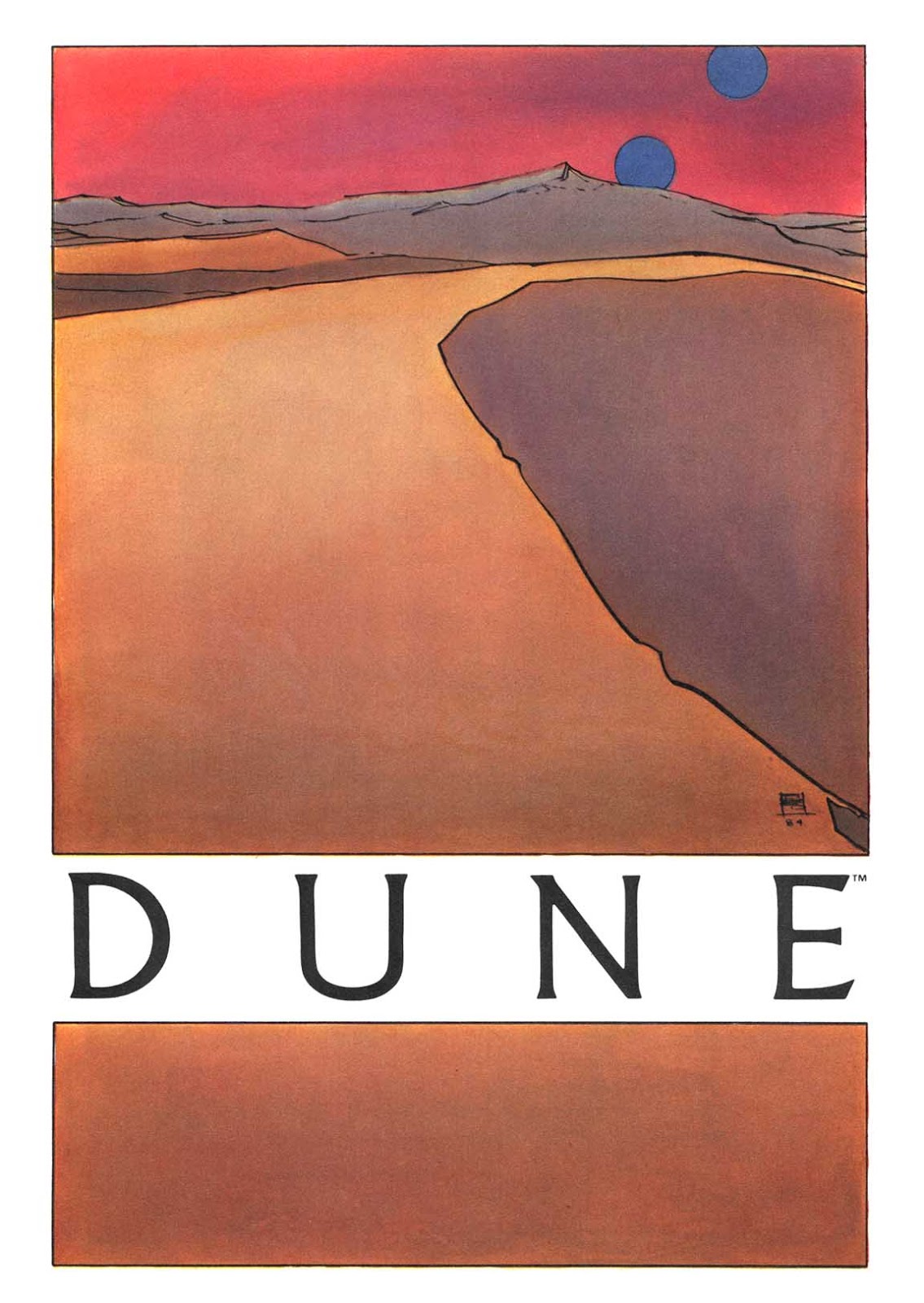

Bill Sienkiewicz, artist: Dune is sort of where my style evolved, because I was trying out a bunch of different pen points. Part of it was an artistic, stylistic choice to break things down into shapes. I remember that I did several versions of the opening page of the desert, I did one with the sandworm on the horizon, and another, which was just the moons and an actual dune.

What I did on that one page, I realized, there was a simplicity to it that I really loved. It just felt really austere. I like the crispness of the more geometric shapes, but also partly because it was different pen tips I was trying. I realized that I could actually approximate a circle or a curve by making a series of slow, short, sharp hash lines. The angular aspect was something I really found appealing. I also wanted something that would allow a decisive stroke.

Christie Scheele, colorist: Bill hoped to color it himself. A lot of times when comics artists want to color their own projects, they’re terrible at it. But Bill started, and he did a couple panels, a couple pages. They were absolutely glorious, because Bill is a painter as well. I could see why he quit too, because he was turning every panel into a fully blown painting. And I couldn’t measure up to that, as he realized he himself couldn’t measure up to that and do it in under a year. But it was a nice way to launch it, for me to see what he had done first.

Bob Budiansky, editor: There are always deadline problems, especially dealing with movie studios, where you have to get the work done on time, then you have to get their approval, then they say, “We want these changes. And you have to rush the artists to make these changes.”

Bill Sienkiewicz, artist: It was such a compressed and full deep dive into dealing with Hollywood at the time. It was a really special project because the buzz for it, and the expectations for the film, were pretty high.

Ralph Macchio, writer: I didn’t have to do too much in the way of rewriting. I know there were things they definitely wanted. They were certainly sticklers, but I don’t remember it being absolutely horrible. I wanted to please them, they were the client, and I approached any of these projects that way. I always tried to be professional. And even if things were fraying at the edges, I wanted to be the guy who was the team player still and came through.

Bill Sienkiewicz, artist: We had a conference call with the studio liaison, where it was Budiansky in his office and myself. So I was sitting on the sofa with the coffee table to my left. Bob was sitting next to me, and we had the phone on speakerphone.

And we were going through all the pages. Bob would just hand me the page and offer any tidbits. And at one point, I was ready for another page, and there was no page coming. And I just remember feeling this weight on my shoulder. What happened was, his eyes glazed over so much from all of the minutiae from the liaison, that he actually fell asleep against me. Bob is a trooper, and he was great to work with. I would have probably done the same.

Bob Budiansky, editor: The studio was real sensitive about character depictions, making sure that Bill got the likenesses right. There might have been a couple of conversations about Kyle MacLachlan, what he was supposed to look, etc., but I had those kinds of conversations in every book I edited. But Bill was very cooperative. He did have to redraw a couple things here and there.

Bill Sienkiewicz, artist: There was this back-and-forth about the villain, Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, and how I drew him. The studio liaison told me, “You’ve put way too many pustules on his face!” It became this bizarre kind of haggling with the liaison. I said, “Look, I’ll remove the pustules from one side of his face, if you allow me to draw him 200 pounds heavier.” It became literally that kind of negotiation.

Tom DeFalco, executive editor: We sent it to the producers for their approval. And they were very discombobulated by it. They said we hadn’t followed the story. So, I remember a group of us went up to their offices to try to figure out what the problem was. Because Ralph Macchio, who was known mainly as an editor, really was a meticulous writer.

They start talking about these scenes that we did not have in the comics—and scenes that we did have in the comics that were not in the movie. I was just completely befuddled, because you can’t do every scene, you’re doing an adaptation, you know, not a direct translation.

Bob Budiansky, editor: You want to be able to capture the feel of the movie. The writer is writing based on the script. But there’s an economy of words in a comic book. You have to be able to boil it down so that the narrative is carried through visually and add the words without clogging up every panel with reams of dialogue. You need to allow the panels to breathe a bit. So you need to have a writer who knows how to read a script, and pull out what’s important so that the story is told as the comic book moves along. That’s the synergy.

Tom DeFalco, executive editor: We pulled out our script, because we brought it with us. And they looked at it. They said, “Where did you get that script from?” As soon as they asked me that question, I knew there was a big problem.

I said, “We got it from you!” And then they pulled out another script, which we were looking at and comparing…and it was almost like it was two different movies.

And they said to us, “OK, but this isn’t the current script anyway.” They had another script, where they had written all over the script—which indicated to me that even they weren’t done with it. They basically said to us that they were rewriting the film in the editing room and would never go back to the script.

I said, “If you want us to try to get closer, give us this script, and we'll make whatever corrections we can make. Because the clock is always ticking, especially in those days. We basically had a two- to three-week window to sell these comics, so we had to make our printing deadlines.

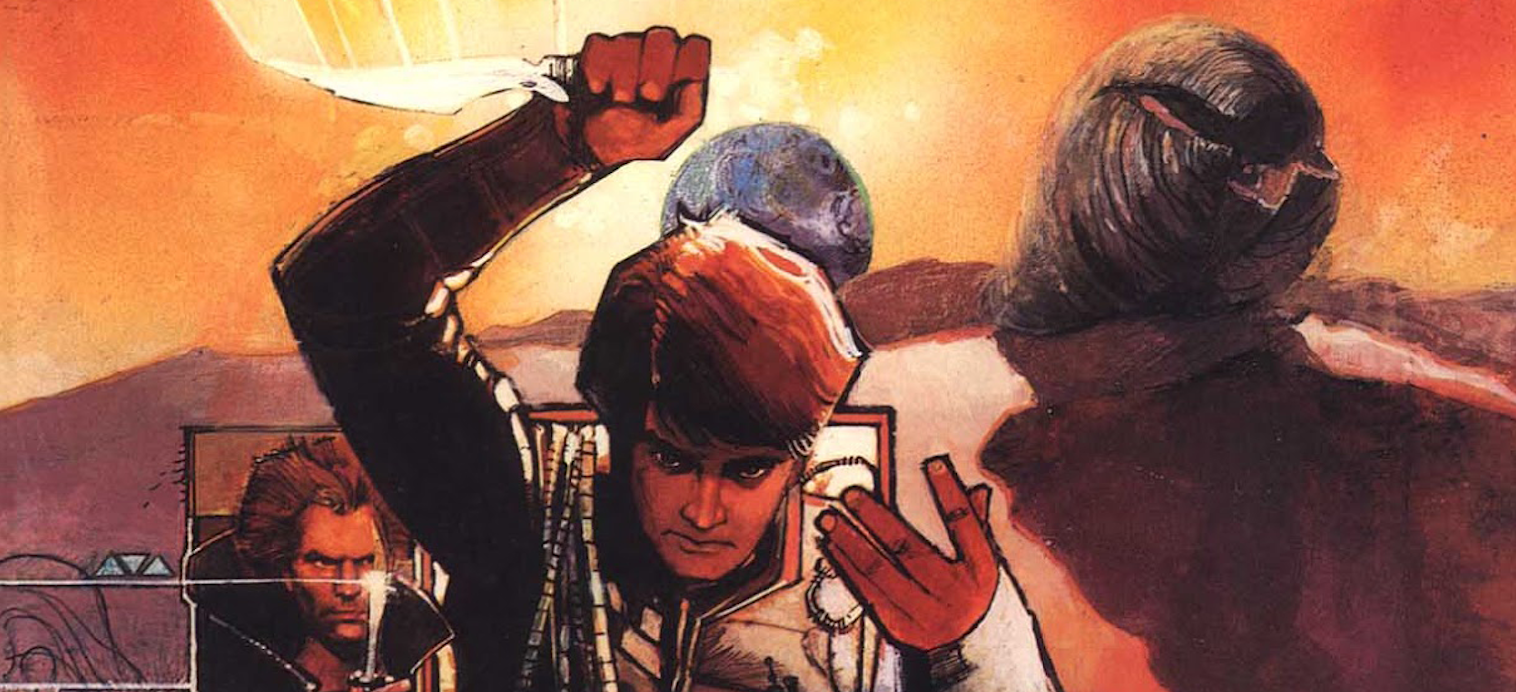

Bill Sienkiewicz, artist: I remember sweating razor blades over the Super Special cover; it just wasn’t coming together. I just hated it. I was pushing more into some of the design elements of the movie poster. When I turned it in, I felt like it was an absolute train wreck. It was one of those pieces that when you look at it later, you realize “Oh, OK, that was kind of a transitional piece.” It was actually much better than I thought.

You forget about all the sort of recriminations and accusations that you go through when you’re in the process of creating. Something where all you see are the failures and the fight. I also did a couple of versions of the paperback cover because they wanted me to move a couple of things. Again, because this is pre-digital, I had to paint a brand new piece to make any kind of changes.

But when I look back at it, I think this actually works pretty well.

Bob Budiansky, editor: Bill did a good job of capturing not only their likeness, but he turned them into Sienkiewicz characters. It’s this really amazing sort of alchemy that he pulls off. He made them very dramatic and there’s a gravity attached to them. Bill did some of the most amazing covers.

Bill Sienkiewicz, artist: The toughest part of the whole experience was going to the premiere. My girlfriend was with me; I think Chris Claremont was also there. And I was super, super excited. The hair on the back of my neck stood up because I’d been involved with this project for months and months and months. And I had so many high hopes for the film, loving Lynch. When the film opened there were things about it that I absolutely loved and I still love. But it was a mixed bag. It’s not perfect, but I have a bias in favor of the film.

Tom DeFalco, executive editor: I really don’t recall the actual film. To be honest, I’m not even sure if I actually ever saw the actual film.

Ralph Macchio, writer: There may have been some flaws in the film. But it was something I was able to pass over. I thought the film was just visually very striking. And I have to say, I thought they did something very, very, very interesting with it.

Bob Budiansky, editor: The people who worked on the book, including myself, went to the preview of the movie, before it had been released to the public. I think we all came out thinking, “Well, our adaptation works a lot better than the movie did.”

Bill Sienkiewicz, artist: I felt that I accomplished what I set out to do, which was to show that comics could do film adaptations as opposed to just simply being the latest Happy Meal or Slurpee cup. So much of the project was about the battles, but to know that you’re working with professionals who have a similar vision and have your back—they’re the people who make it all worthwhile. I am still incredibly proud of it.

* * *

Robert K. Elder is the author of 15 books, including Hemingway in Comics.