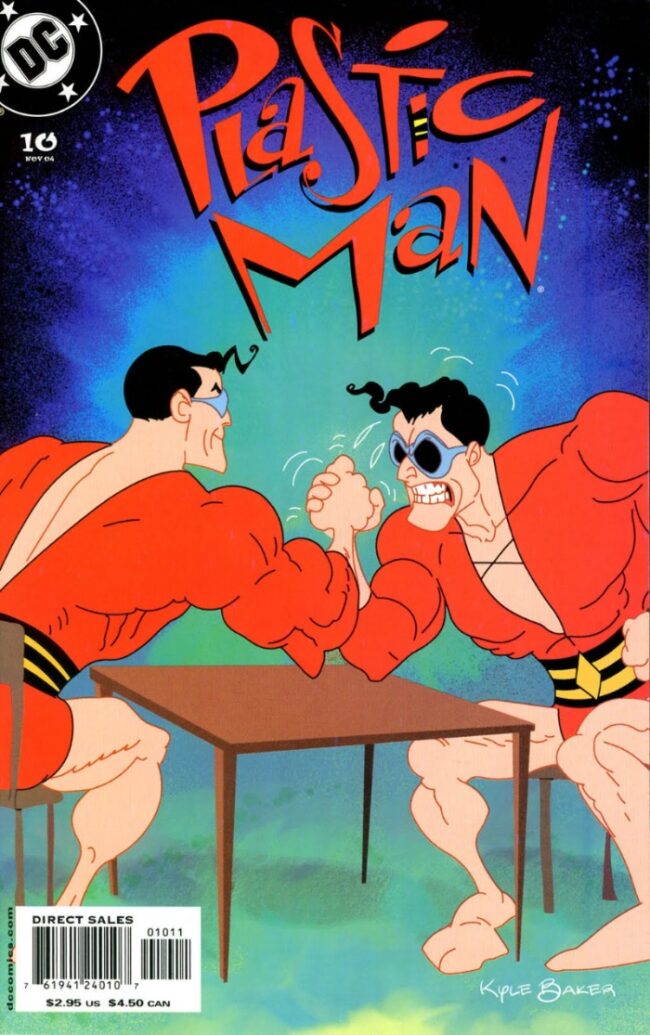

Kyle Baker's Plastic Man is coming back into print. Over fifteen years after its original publication it will soon get the omnibus treatment, a hardcover collecting all 20 issues of the run. It's more like 18 actually, as two issues are drawn by Scott Morse (and though they are not ‘bad’ per se they still feel like a fill-in). That the run gets an omnibus treatment is not surprising, that it took DC for so long is. After all, the series is of that rare breed of DC comic-book – the critically acclaimed type. It nabbed no less than five Eisners (despite only lasting two years). That’s a lot of awards, and yet the series languished in publication limbo like the red-and-yellow covered stepchild that it is.

Maybe I shouldn’t be too surprised? Ever since acquiring the character, when original publishers Quality Comics went bust in 1956, DC has never seemed to quite know what to do with him. There were several series and mini-series (the last one in 2018) but none of them has left much of a mark. The character has been forced into the central stage in the pages of JLA and Justice, later into various crossover events. All of these appearances only highlighted how ill-at-ease Plastic Man feels amongst all these self-serious characters, especially when drawn in the mode of pseudo-realism brought into vogue in cape comics in our post-Neal Adams, post-John Byrne, post-Jim Lee age. Plastic Man should feel out of place: he’s a man in yellow and red shorts with no understanding of proper pants length. But in mainstream superhero comics he’s the wrong type of out of place. He's slapstick creature in the midst of a bunch of epic operas.

Of course, it’s pretty clear why DC doesn’t know what to do with him. Plastic Man wasn't a character made and liked for his rich inner world and iconic symbolism – he was made as a vehicle for the skills of a particular artist, the character’s creator Jack Cole. Cole has long been admired among his golden-age comic-book artist brethren; said to own artistic skills on par with the more renowned newspaper artist of the period (Cole actually left the comic-book industry for a lucrative illustration job in Playboy, which showed his more illustrative qualities). Indeed, one of the alleged reasons Cole left monthly comic-books was the pace they required; for Cole, sacrificing the quality of his work wasn't an acceptable compromise.

Cole was the subject of a fawning article by Art Spiegelman in the New Yorker (April 19, 1999). These were the halcyon days - before Chris Ware was engineered in a lab to bring the word of comics to New Yorker readers like the Silver Surfer heralding Galactus; the idea of doing a fawning feature about comics, and a jokey cape comics at that, might have been shocking. Spiegelman’s usual self-deprecating shtick is stretched to its limit (“I’m embarrassed to confess to being in love with a superhero comic, but Jack Cole’s “Plastic Man” belongs high on any adult’s How to Avoid Prozac list”), but his appreciation of the work is genuine. He (and designer Chip Kidd) later expanded it into the book Jack Cole and Plastic Man: Forms Stretched to Their Limits. As Spigelman says, without really saying it, the success of Plastic Man was heavily dependent on Cole’s style. He wasn’t a Batman or a Superman that could flower under different artistic control. Plas was Jack Cole’s world, and without him the series waned.

Spiegleman’s article was correct in its appreciation of the formalistic brilliance of Jack Cole – here was an artist who took full advantage of his creation’s malleable shtick, transforming both character and comics in radical ways; wallowing in his playful style in a manner, with every string its own tiny celebration of creativity. His stablemates in Police Comics (Firebrand, Agent 711, the Mouthpiece) were all of a type, and equally dull in their stern-faced no-nonsense slugfests (though some occasionally reached brilliance in their straight brutalism). You could switch the titles and masks around and no one would notice. Not so with Plastic Man.

In a story featured in Police Comics #15 Plastic Man takes on a scientist using a weather control machine to freeze Mexico. While most series would present this already-rote idea in the expected manner, Cole instead portrays the character of the North Wind as Greek Chorus throughout the story, looking over the folds of panels and commenting on the plot as Plastic Man stretches all over the place. The story continues its fourth-wall breaking until the machine is triggered at which he point the North Wind his unnatural need to cast cold on the warm region. It’s a completely unnecessary flash of creativity that enlivens an otherwise prototypical mad scientist typical story.

In another story in Police Comics #8, Plastic Man faces a criminal gang using a strange machine that launches gigantic guided billiard balls throughout the city. The story starts strong enough, with a title page in which the letters of Plastic Man’s name are tilted as if they’ve just been struck while a ball goes through three buildings in a row – selling to reader the scale of destruction. Below this presentation is a three panel stretch depicting the device which ends with our evil mastermind so delighted by his own capacity for evil that he blows smoke from his nostrils like a dragon. The rest of the short story is likewise filled with inventiveness, one panel demonstrating the magnetic forces of the speeding wrecking balls by depicting a cowboy sitting on a fence as his gold coins escape from his wallet and back pocket carried on the wind; his nearby friend crying as his gold-fillings likewise fly freely from his mouth.

That story is like a great Mad Magazine piece in many ways - a cloth-line to hang the gags on. Every part of the story, every page and panel, should be crammed with humor and movement, nothing wasted. Still, despite the sheer anarchy, Cole is surprisingly in control on both his art and his story; the great touch that make his Plastic Man stories age so gracefully is that Plastic Man himself isn’t a comedian, he’s a fairly serious character reacting to a crazy world by changing himself to fit every situation.

The mistake made by creators following Jack Cole, and I include Kyle Baker in this bunch, is to miss that seriousness of the character is essential part of the gag. A good straight-man can make or break a comic-routine. Instead, the minute he bounced into the DC universe Plastic Man became ‘the funny one’ often written by people who don’t really know how to write good gags and artists whose style fails to convoy the right sort of energy. Like CC Beck's Captain Marvel, Plastic Man lost something when he was taken out of his own whimsical universe, defined by extremely idiosyncratic creators, and forced into the wide open sandbox of shared superhero universe. There’s a flattening effect going on with the DC universe version of Plastic Man.

That being said ,Kyle Baker’s Plastic Man does two things (the things that matter most) right: first, it puts the art in the center. As described in Modern Masters: Kyle Baker (in which includes Baker predicting he’ll never get a positive review for something like Plastic Man in The Comics Journal) Baker saw the malleable character as a chance to experiment and try different techniques, especially when the book was given extra life beyond the initial six issues (explaining the Scott Morse fill-in story). The first story arc being completely digital, two issues drawn with no outline, pages modeled after original Jack Cole art, painted scenes evoking Alex Ross etc…it’s Baker spreading his already considerable wings, and doing so in a manner meant to entertain.

My favorite is issue #14, which doesn’t pretend to be anything other than a series of Loony Tunes-esque gags, with Plastic Man hunting down a terrifying home invader – a mouse! It’s just one joke after another: Eel O'Brian reaches his long hand into the mouse hole and gets bitten, he turns himself into a mouse trap and nabs his own fingers, he transforms into a sexy-lady-mouse and finds himself leaving the mouse-hole (supporting an extremely befuddled look) accompanying several mouse babies. There’s even an eyes-pop-out-of-their-socket joke – with the eyes actually breaking glass.

The other important aspect is that the book is funny, and in that it’s critic-proof. Whatever other criticism I’ll have it could always pull the trump card – it made me laugh. Having accomplished that, everything else is of little consequences. I’m not sure there’s an artist besides Baker who could do the series justice nowadays. There’s always been something quite rubbery about his characters, a certain squash and stretch sense to way they moved, an extra step to the movement, as if the muscles are threatening to burst of their own skin. Even in his brief run on The Shadow, you see this trend manifests as the Shadow towers over terrified villains, popping out of nowhere, like Bugs Bunny out of one of his holes.

Plastic Man might not be Baker at his artistic zenith (Why I Hate Saturn is probably superior in terms of writing, and King David in terms of craft) but it feels like the type of thing he always meant to do – the place where he can express himself most freely. For a DC title it’s surprisingly loose-limbed, not just in terms of its relation to continuity but in the complete control he was given over the title. Baker writer, draws, colors and letters; besides Joey Cavallari's editing credit, otherwise it is a solo project.

Look at the page above – simple in terms of structure, and relatively static in appearances. Yet Baker nails the proper responses while playing with two shape-shifting characters: the plastic child preserving the sad face as he transforms into an octopus, Morgan’s delayed response as the realization dawn on her, Plastic Man’s slight metamorphosis as the pressure applied to him for several different directions. It’s a reminder that Baker can often find comedy both in the sitcom formula while going all out as a cartoonist.

Cole was idealistic, which manifested itself in his dedication to his work and within the work itself; his Plastic Man is almost naïve in his good-naturedness. Always trying to save wayward souls, like he himself was alleged to be. Baker was always more cynical (or is ‘knowing’ a better term?). Once he recalled his father (a professional artist) warning him beforehand about the perils of the comics industry: “I would say, “Gee, dad, I sure would like to be an artist when I grow up. I wouldn’t mind being like Jack Kirby.” And he’d say “Well, Jack Kirby didn’t make a dime.”” (Modern Masters: Kyle Baker). You can sense a certain remove in Baker’s work, as if he looks at the characters from above (especially if they are corporate-owned).

This isn’t much of an issue in Plastic Man, a book whose approach is wholly cynical from the go and whose use of feel-good sitcom tropes is in the service of self-annihilation. The idea that you might feel emotional attachment to these idiots is itself a joke. Yet, despite how cynical he is about the business of comics Baker’s Plastic Man project feels artistic; like a cartoonist testing his limits. Sometimes he oversteps them, issue #11 in particular feels flat and weightless – the design makes the characters feel like blotches of color squashed against the background. Baker understands mass, after all, so this feels like an experiment gone wrong.

Plastic Man might be DC’s character but in these comics, it is Baker’s vision being expressed. There’s a lot of joke at the expense of modern DC comics, and I mean a lot. A good quarter of the series, spanning the last story-arc, is about how inappropriate the grim and gritty melodramatic tone of superhero comics with basic design and ethos of these character.

I both like this and hate this. Like, because (as mentioned before) Baker is really good at delivering jokes – a scene at superheroic funeral signed by a row of female character standing with their large breasts pointed forward like they’re in a Russ Meyer production. It’s a perfect encapsulation of all the terrible self-serious trends, death of beloved childhood characters as shock, dark atmosphere as cover for inane writing and the restless sexualization of female characters, even when pretending to be solemn. What can I say – it’s all true! Hate, because it’s also a soft target (even in 2004 and especially now), and one Baker keeps going at. It’s tiring, especially when it stops the more physical aspects of the comedy.

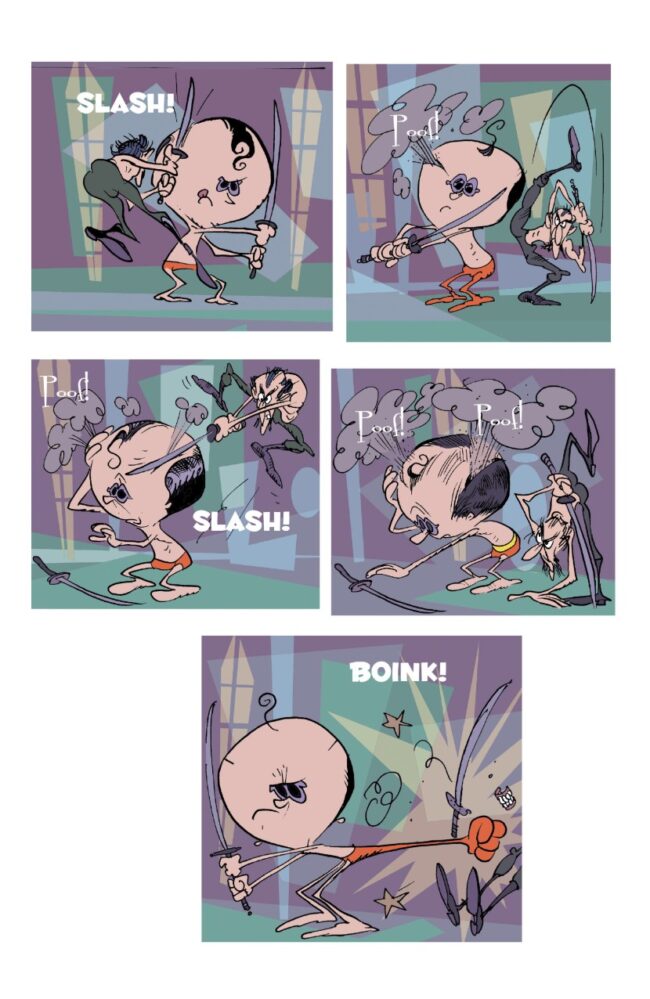

The problem of the series is the parodic elements begin to dominate after a while, overshadowing the more fanciful and pleasurable cartooning. Baker is still bringing his A-game, there’s some top-notch fight scenes, especially the ones directly aping Neal Adams, with the story constantly finding excuses to keep Plastic Man occupied in holding the ashes of his departed family (don’t ask) while holding back a dozen ninjas and a shirtless Ra's al Ghul. There’s so much stuff happening on the page, and it is to Baker's credit that he can keep all straight while keeping his character malleable.

Cole’s Plastic Man was a fairly serious story adorned with gags, and Baker went for madcap from the get go – everything is crazy and pretty much everyone is stupid. It’s probably for the best it only lasted for such a short while, as there’s limited shelf life in bunch of morons running around getting on each other’s nerves. (Ed. This is inaccurate.) Still, for all its faults, for the try-too-hard and the try-too-little moments, Plastic Man still uses his butt to open a door, which, to me, is the highest measure for art.