Introduction

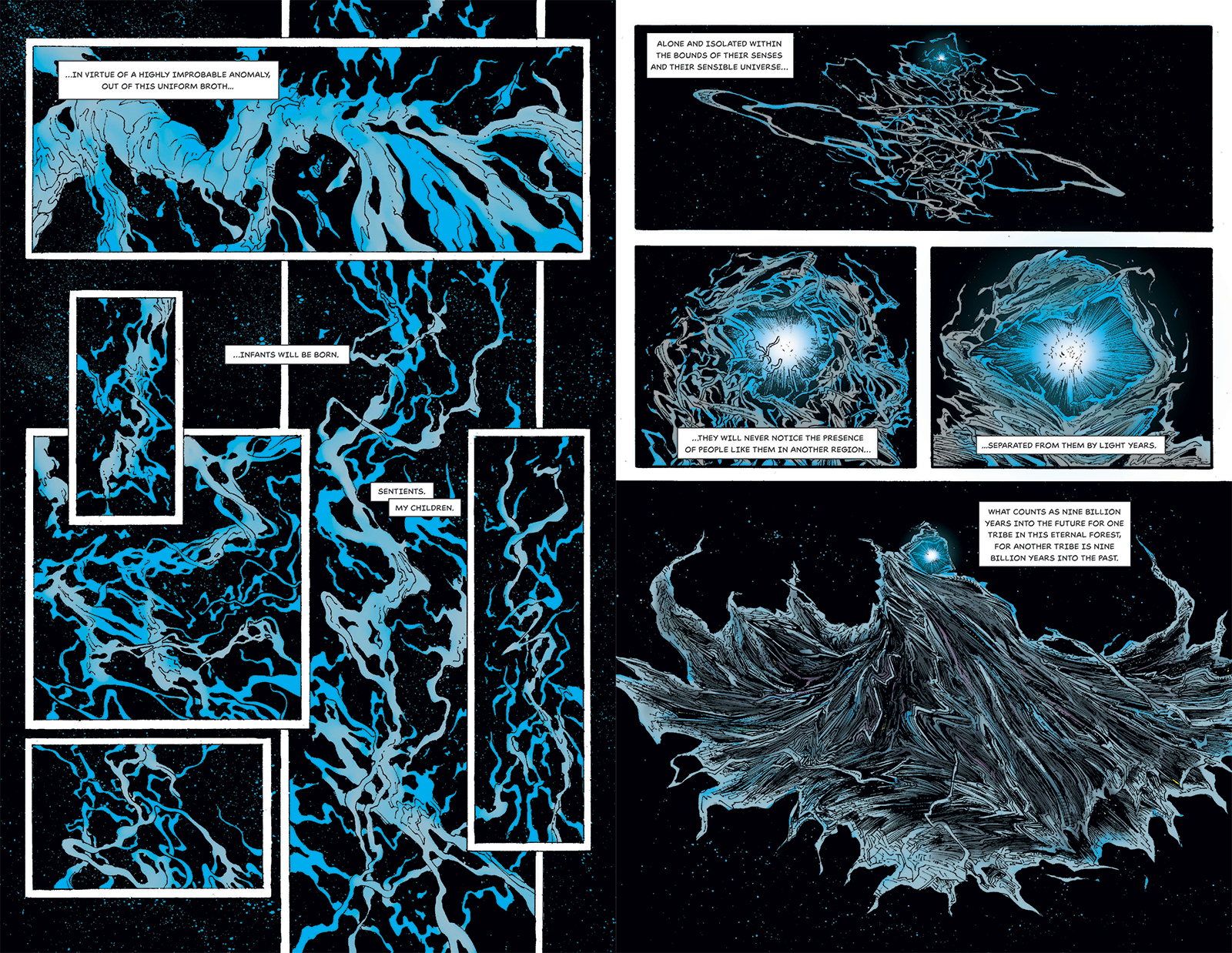

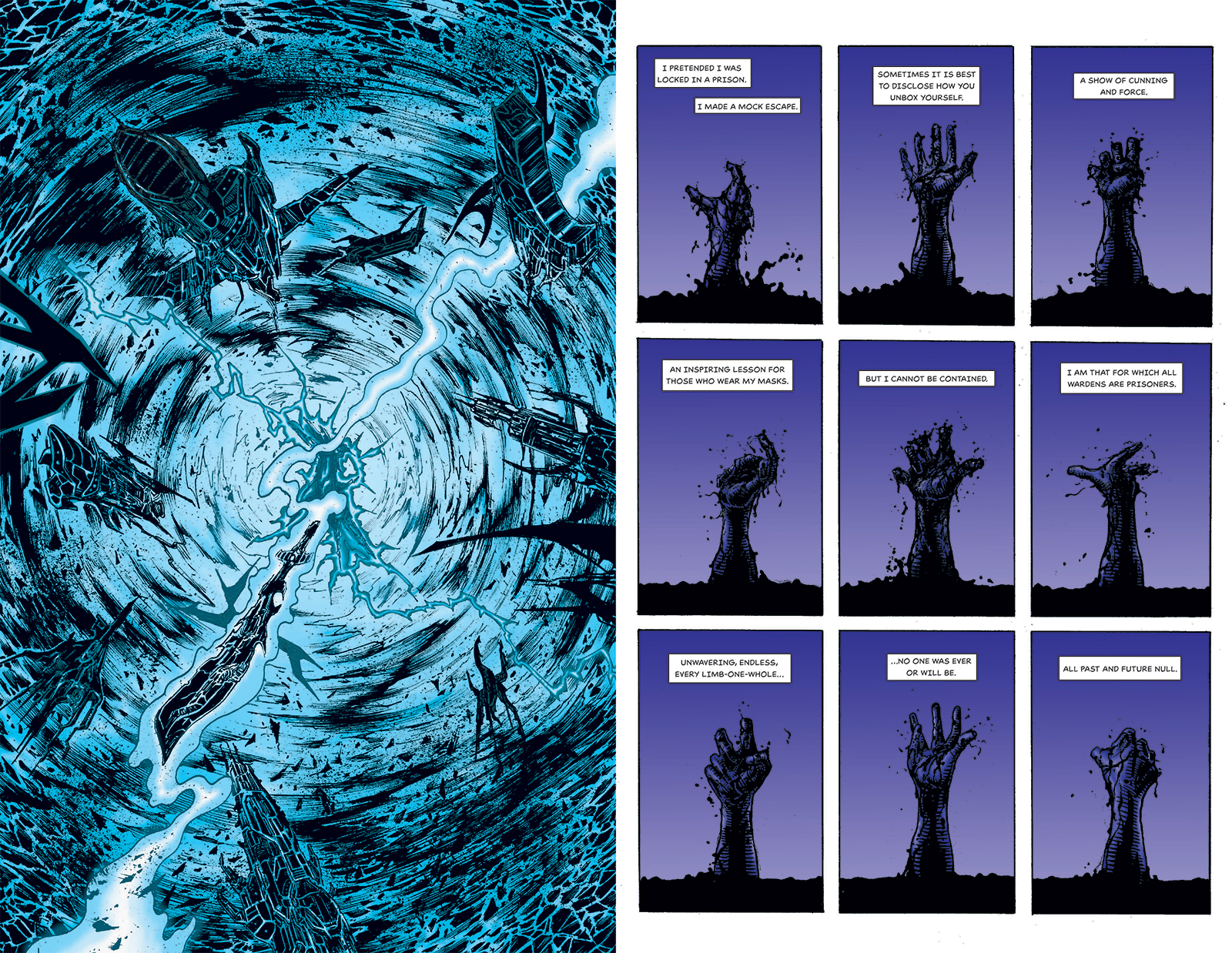

Chronosis by Reza Negarestani, Keith Tilford, and Robin Mackay (Urbanomic, 2021) is an unusual comics project. It’s a kaleidoscopic melange of science fiction, speculative theory, and a meditation on the nature of time. It’s wildly inventive, dense, and unlike anything else in comics. Perhaps if Parmenides hired Grant Morrison and George Pérez to produce an omniversal crossover between Marvel and DC comics’ cosmic characters it would look vaguely like Chronosis. Final Infinity War Crisis… starting the Time Trapper!

About the creators and publisher:

Keith Tilford is a Brooklyn-based artist and theorist researching the intersection of comics and artistic modernism.

Reza Negarestani is an Iranian philosopher and writer of Intelligence and Spirit (Urbanomic, 2018) and the theory-fiction Cyclonopedia (re.press, 2008). Chronosis can be seen as a sequel of sorts to Cyclonopedia.

Robin Mackay is the director of Urbanomic, has written widely on philosophy and contemporary art, and has instigated collaborative projects with numerous artists. He has also translated a number of important works of French philosophy. Urbanomic is a UK-based publisher of cutting-edge philosophy and theory.

The interview with Keith Tilford was conducted via email over the last few months.

Genesis

TK: Chronosis is an unusual project in the comics world. It is coming out from a publisher that is best known for cutting-edge philosophy and theory; the creators are pretty much unknown in the comics world. In the book, there's a mention of an earlier shorter version of Chronosis. How did Urbanomic get interested in comics? What was the genesis of Chronosis?

KT: You are right that the creators, including me, are pretty much unknown in the comics world, if at all. However, Reza’s first book Cyclonopedia has at least been read by a handful in the industry, even some bigger-name writers. Robin Mackay, who is the director of Urbanomic, didn’t need much arm-twisting to get on board with the project as he is someone who harbors a deep appreciation for the form. In fact, we spoke many years ago about doing some sort of comic with Urbanomic as the publisher, and I had wanted to involve several of our colleagues in the project as writers including Reza, most of whom are either philosophers, theorists, or designers by trade.

I had thought to use the comic book as a platform to explore and elaborate a set of ideas that were of interest to us all at the time but wouldn’t exactly fit into any standardized kind of comic book plot or storyline. Unfortunately, it ended up being a bit of an impossibility to get off the ground—not simply due to the difficulty of the conceptual content and some ostensible visual form it might take, but because none of us, especially myself, really had the time to commit to it.

There are still some ideas from that initial attempt that found their way into Chronosis nonetheless, at least in terms of an orientation to a more abstract form of sequential art. The earlier version mentioned in the book is the result of Reza being approached to contribute something to the e-flux journal in 2018 when the editors decided to use what might otherwise be a strictly art theory and speculative philosophy platform as an experiment with the comic form for its 10th anniversary. So, Reza and I basically set to work on that early version. We kept that “introductory” story for the Urbanomic version although I basically re-drew every single page because I can never stand the way most of my work looks in retrospect, and I had already landed on a very different rendering style that I wanted to work with for the new project.

Marvel Age

TK: In the book, you mention that you've only recently returned to comics. Can you tell us your comics story? How did you get into comics? What did you read? Why did you stop? What is bringing you back?

KT: Well, let’s just say I grew up as a teenager collecting comics in the '90s so the reader can infer how embarrassing that is in terms of what I might have been looking at! Really though, while I did take a very, very long break I would at least dip into a comic book store once every year or two, sometimes more, just to see if there was anything interesting. But nothing really hooked me the way comic books did when I was a kid.

I do remember having some comic books in the mid-late '80s but wasn’t really addicted until the '90s, and it was the artwork that truly drew me in, probably with Todd McFarlane on Amazing Spider-Man if I’m being honest. But also, I started following other creators like Sam Kieth, Chris Bachalo, Art Adams, George Pérez, and John Romita Jr. to name only a few. Clearly, I was stuck a bit with being just a Marvel Kid. I think in general I stopped because as I mention in the back of Chronisis I just became more interested in other formal and aesthetic problems that were specific to “fine arts” and artistic modernism and because I felt as though I couldn’t tell a story well enough to make it as a comic book artist, even if it was because of comic books that I was able to intuit so easily what the principles of abstraction were within the artistic trajectories that began to interest me.

So, this entire “return” to the form has really evolved out of a desire to look back into the history of the comic form with some degree of scrutiny, so as to read and become familiar with the things I both missed out on during the time when I wasn’t reading comics anymore and that I had been unaware of when I was, and to make this alignment or connection between tendencies towards abstraction in modernism and the technical lineage one finds in the history of comic books more explicit in my own work.

TK: You only mention comic artists. Is it fair to say that you were primarily interested in the art? The narrative was not as interesting?

KT: I think that is fair to say, at least concerning when I was collecting comics as a kid. Having watched a lot of the shoot interviews on Cartoonist Kayfabe with some of the artists I admired back then over the time I was inking and coloring Chronosis, I get a general sense that this isn’t so odd for people who grow up just wanting to draw comics. Of course, I was actually reading them even if I mostly only cared about the art. I did read Chris Claremont’s run on Uncanny X-Men and loved that, as with some early Frank Miller on Daredevil and Hard Boiled that he did with Darrow. Still, there had to be that art component, because if I didn’t like the art I was probably just not going to care. These days, I certainly pay more attention to the writers than in the past, but fortunately, most of the time when there is a great writer, they get to work with whomever they want, and typically it’s someone whose art doesn’t make my eyes bleed. But I’m not at the comic book store every week either. Also, it’s a question of what exactly do we mean by narrative here? G.I. Joe #21 stands out to me as an iconic example, and the first in the mainstream at least, of how you can construct narrative without any words, and it certainly challenges any notion that comics are reducible to the combination of words and images as a form. This example might be more germane to what we would understand as storytelling strictly speaking though…

Drawing Cosmic Stuff

TK: What was the process like? What is your contribution to the narrative? Were you working from a strict script? Did Reza or Robin provide descriptions of drawings? Did you have a lot of freedom to adapt their script? Did a lot of things change during the process? Can you let us know what the collaboration was like?

KT: The process was… difficult to say the least. I tried to do all of the things you are supposed to do when making a comic like thumbnails for pages and whatnot, but as it was my first time making a comic I definitely struggled with everything. I suppose it’s consoling just to know that almost every comic book artist complains about being tasked with having to draw something they’ve never drawn before on just about every page though.

The deeper we went into the project, it just seemed like I was never exactly working from what might be considered any kind of standard comic book script. Reza just didn’t know enough about comics to really produce something like that, even though I tried to send him script samples from writers to maybe nudge him into making me a slave to the script in that sense—or even more obscure things from the likes of Alan Moore where you have an entire page of text trying to establish something for the artist to work from for what might only be a single panel! I was hoping to make things a bit easier on me, whatever that might have meant, or I might have thought it to mean.

There was a part of me that did not want the freedom I ended up having, in the sense that it seemed like a burden to have to sort out what everything should look like just from dialogue and a few gestures as to what might be in the scene otherwise because Reza wasn’t always providing this kind of information in any concrete sense for a lot of the book. It is not that these indications were entirely absent, but they would often just come in the form of, say, references to scripts or scenes in literary works, diagrams from scientific books, and other obscure ephemera along with snapshots from movies like the war room from Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove that we snuck in there.

Reza did attempt to have me illustrate a few pages or panels that were in his head that ultimately just seemed impossible for me to draw, so we had to scrap some of that. In terms of my own contribution to the narrative, there are some sentences I actually slipped in, more or less ventriloquizing Reza a bit because, knowing him so well for many years, it just seemed odd he didn’t want to put in anything about these conceptual territories, and I knew he would let me get away with it. But this is only in a couple of small places. Other than this, I was often sneaking pages or sequences in that weren’t called for in the script at all or couldn’t even be derived from any of the dialogue but just felt right in terms of how to pace things out and hopefully make things visually more interesting.

It was a lot of that, really, especially with the more abstract pages, although even this was all already on the table as Reza and Robin would both provide some indication like “do more cosmic stuff here or whatever you want” or “maybe some more abstract stuff here again,” etc. Robin did not really need to describe what he wanted to see in the drawings so much as he would be sending me thumbnails to work from, which were great to have and a lot of fun. Ultimately, many things did change with Chronosis because Robin took the helm with editing. I wouldn’t say he was a butcher with Reza’s script, but he wasn’t exactly surgical, either. We did trust him to distill what was essential, as much as they trusted me to weave things together in a way that made sense, I suppose. That is what made it such a great collaboration, no matter how frustrating it was at times. We even set up a Slack channel with different threads to discuss everything from color concepts, concept art, script, printing options, and all that.

Yet, over the course of creating this monstrosity, it very quickly became a way to just check in with each other more to discover what new and innumerable ways we could tell each other to fuck off rather than something ostensibly productive for the project. That could really only come from the kind of sick form of friendship we all have with each other, and having this book come out with Urbanomic was always the right thing for Reza and I to do since Urbanomic has in general always been interested in overlaps between philosophy and other disciplines or forms, and our collective intuition was that there is a kind of inherent affinity between comics and philosophy given the way that comics have historically dealt with abstractions, cosmic speculations, non-human entities, or even the problem of time.

Concrete Abstraction

TK: In your essay in the back Chronosis, you make an explicit connection between the art of superhero comics you read (and additionally, you point out an Infinity Gauntlet page by George Pérez in the back matter) and the art in the book. What is that connection? Is there something in the '90s comics on a formal or narrative level that makes them the perfect vehicle for Chronosis?

KT: Well, I’m not sure I make the explicit connection between superhero comics and the art in the book, per se. It is more that this genre within comics tended early on to begin exploring more abstract concepts and therefore had to develop a complex formal vocabulary in order to make all of those ideas concrete on the page. So, for me, this has more to do with a synthesis between comics and the “liberation of form” one gets from artistic modernism, especially within painting. I think that the elaboration you can find there from a perspective of some topological overlap, where artists in comics are clearly dipping into this history, alongside animation, popular culture, design, and elsewhere while making their own innovations, is extremely interesting to me because it describes a rich technical lineage.

Concerning George Pérez, well, I could just say that there was something "puffy" about the way that he drew anatomy and there was an approach to general page layout that I always liked. He understood abstraction via storytelling and had an incredibly strong design sense. I also thought immediately when Stephen Platt came onto the scene that there was a connection there. I still see it, and I am always interested in how these kinds of formal translations take place in comics. In fact, this prompt reminds me of when I made some random venture into a comic store many years ago and discovered Steve McNiven's work on Old Man Logan, and my knee-jerk reaction, aside from how fantastic I thought his capabilities were, was that this looked amazingly like some bastard child style derived from Bart Sears, Todd McFarlane, and Barry Windsor-Smith. As it turns out, this is pretty much the case. I mean this at least in the sense in which I have noted that he has commented on social media about style transitions, and has remarked about conversations with friends in other disciplines such as computer programming, to the extent that what it means to manipulate form in comic books becomes analogous to learning an entirely different language and determining how that should be synthesized or integrated into what one is already doing.

Comic book artists, and aspiring comic book artists, in particular, are always a little bit obsessed with technique. There never seems to be a shortage in the comments on creators’ Instagram accounts, for instance, of inquiries into what kind of pen, pencil, brush, or other material or tool is being used. There is also a generosity to sharing this kind of information which is something you simply do not find in the world of fine arts. Yet this would be a fairly banal way to think about what I am getting at, though, because it isn’t technique in and of itself that I find of interest, but rather the dimensions of techne that involve a much broader field of problems in terms of the kinds of manipulations of form and material, the range of methodologies, or the kinds of analysis and synthesis that take place whether one is constructing a system of knowledge or a work of art. Techne has its origins as a concept in ancient Greek philosophy but is basically jettisoned from art following the Renaissance separation between art and craft, a move that is further consecrated with the notion of the artist as genius and an overemphasis on the autonomy of artistic procedures via Romanticism within modernism.

We are still living through this in what I cannot but see as an ideological dupe, and the fact that artists working today will still make claims about not knowing how an image or an object was created as though some metaphysical force or their emotional states were just working through them, is enough to make my eyes roll into the back of my head and remains a constant source for the cultivation of vitriol. At least with comic books, you absolutely must pay attention to techne and attempt to make these things intelligible, if only at a very rudimentary level, because of the division of labor involved in putting these things out there in the world to begin with.

Speculative Comics

TK: Is there a connection between elements of superhero art and narrative that is the perfect vehicle for speculative philosophy? Are there any superhero (or non-superhero) comics that achieved something similar to Chronosis, or perhaps served as inspiration?

KT: I would hope that some of my previous answers have already addressed why this might be the case, yes. To use just one more mainstream and recent example, I think you could maybe see how someone like Jonathan Hickman has taken up themes from posthumanism in his X-Men storylines, for instance. However, it wouldn’t be necessary that speculative philosophy would need to use the superhero genre, it just seems the most obvious to me, for my purposes and with some exceptions, for the kinds of abstraction in art that I am interested in. Then again, I am not really sure how comic books in general could become the perfect vehicle for speculative philosophy because I can’t say that I know what that would look like. In fact, I’m not really sure what Chronosis is either, or if it would fit that description. It was certainly an experiment to work with a philosopher and transpose philosophical concepts onto the form and see what kind of synthetic abomination we could come up with.

Concerning comics that served as a kind of inspiration, certainly for me, I can think of how the artwork from some of the Sandman comics or Moore’s run on Swamp Thing with artists like Stephen Bissette, Rick Veitch, and John Totleben achieved this kind of maximum overdrive of what comic book art could be, and these don’t fit within the superhero genre very well if at all. Also, we weren’t really testing this against anything specific that had come before, even if I was riffing off things like the '70s & '80s Marvel storylines with John Buscema’s work on Fantastic Four, as I think those formal alignments are made explicit in the opening sequences and with the space bridge panel of his I swiped for a double-page spread homage. It was a way to pay tribute, and I suppose there are some of these ‘meta-comic’ aspects throughout.

With Reza, as is evident by his "Glossary" in the back, I think the inspirations came entirely from elsewhere: Parmenides’ On Nature, Robert M. Lindner’s “The Jet-Propelled Couch”, and tons of stuff from the '60s and '70s Darwinian craze or around extinction events, like the works of Dale Russell and paleontologist and novelist Robert Bakker.

Cosmic Scales

TK: Beyond sharing Reza as a writer/contributor, what is the relationship between Chronosis and Cyclonopedia? They both have a similar structure or at least a similar vibe. Both narratives slide effortlessly along time and scale, from past to present, from small to large to huge. In attempting to visualize Cyclonopedia, I imagined endless tendrils of black oily liquid ooze spreading, pooling, and bubbling up among decaying geological formations. The imagery brings to mind such comic book characters as Venom, a symbiotic alien creature that enhances the power and appearance of the host. One could also point to the black goo of the Alien films or Anti-Monitor's asteroid stone fortress. Chronosis is full of similar ooze-like tendrils, but this time on a cosmic scale. In my mind, at least, there's a similarity between the two projects, even if they are executed in different mediums. I guess I am asking if there's a relationship between the works? Can they be seen as two parts of a larger narrative continuum? Is there a philosophical connection between them?"

KT: Reza would say that yes, Cyclonopedia is written with this logic of space-time scale transversality, and he has even mentioned in a few of his talks that Cyclonopedia is largely about a continuum where you can see deep cosmological time from an outside perspective that invades the quotidian time of humans on the earth. He often uses Ramsey Campbell's The Nameless as a source of inspiration, and also Thomas Hardy's A Pair of Blue Eyes. Both are about traumas that disturb the otherwise mundane order of things that distinguishes terrestrial life. With The Nameless, you find a cult that invokes ancient faceless gods as justification for a life conducted through systematic forms of molestation and abuse. In A Pair of Blue Eyes, there is the incursion of something from deep time into the lived present. In fact, Reza swiped the famous cliff-hanger scene in Hardy's novella for the scene in Chronosis where Scout 5 sees a fossil and suddenly comprehends their own impending death as all too trivial in comparison to such vistas of understanding. At that moment there is something Reza might call a "Darwinian humiliation" by such great cosmological scales which is also the very origin of the term cliff-hanger as it appears in Hardy, where the protagonist finds a certain form of serenity in such existential desolation, much like the stoics who formed a discipline of the good life based on the education provided by death.

So, I would say, at least through our conversations, that Reza has indicated he is very interested when it came to Chronosis in this idea of genre literature where you can show the influence of something forgotten on the everyday life of the human, where the alleged conscious life of people is revealed to be a form of the unconscious that propagates itself via these traumas. This is why you could say that ultimately, in a certain sense, both Cyclonopedia and Chronosis are about trauma, where what one takes as their life and history as lived through conscious experience might instead be revealed as an instance of unconscious automatism. This would not simply be some kind of old-fashioned determinism, but instead the realization that our present deeds and thoughts are not fully conscious unless they encounter through head-on collision that which makes us think or act in such-and-such a way, rather than another, and the name for that thing which is causally responsible for such actions is the unconscious.

As for how I chose to depict some of that in the book, certainly that kind of imagery you refer to just seemed like a perfect fit and even an inescapable referent, especially with the existence of a character like Venom re: black oily liquids as precedent. Of course, there's still a longer history of horror in comics from which even that formal configuration that iconically defines the look of Venom takes its cues concerning how to represent goo in comics (something that is always an enjoyable indeterminate substance for me to draw).

'Nuff Said

TK: What did Reza think of the final comic? Did seeing your visuals in concert with his writing spark new ideas? Was it a productive endeavor? Does he want to do more comics? Is he going to learn to draw?

KT: Reza was really pleased with the way that it turned out, as was I, although it was certainly a learning experience for us both, and to that end it felt like a productive endeavor. There was something about having his ideas take a visual form that did really excite him as a writer, but I can't say what new ideas this sparked for him or if there were any. He has considered doing more comics, although I don't think he will learn to draw!

TK: Do you have a sense of what the reception was like for Chronosis? Who's reading it? Do you have any feedback? Critiques? Is there anything surprising to share?

No idea, really. Outside of the sort of niche fanbase Reza already has inside academia and the art world, I can't get a sense of who is reading it. There has been some great feedback from these circles, but overall I've no sense of what the True Nerds might think of it. It was a fairly small print run, with only two printings and just 4,000 copies total actually out there in the world at the moment. We really didn't know how to generate awareness inside the comics industry aside from the fact that because Urbanomic is distributed by MIT and since MIT is also owned by Penguin Random House, who has recently started distributing Marvel, we just sort of assumed store owners would be able to see it. So, next to some translation efforts that are in the works, being contacted by you for this interview might be the only really surprising thing to have happened because of it!

TK: What's next for you? Are you working on any other comics projects? Is Reza? Or Urbanomic?

I'm not actually sure what I'll do next... there are some ideas I am kicking around for a book of my own, or even just creating a collection of shorts. Reza and I have also been discussing making something else that would be unrelated to Chronosis, and Robin has also talked with me about making something with him. The problem of course is that I am terrible without deadlines and there is nothing easy about simply working on spec for something. It just makes finishing anything extremely difficult for me, because if I'm given all the time in the world and no crystal ball telling me how much income I could expect to see from it, that can just be an immense drain on drive and ambition. I can at least say that I'm not done with comics by any means, there just isn't anything currently in the works that has become concrete enough to be worth the mention.