To mark the release of Chris Ware’s decade-in-the-making Building Stories—a box of fourteen print artifacts ranging from cloth-bound volumes and newspapers to broadsheets and silent flip books—The Comics Journal is featuring a series of essays from the contributors to the 2010 volume The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking (University Press of Mississippi). Each contributor is revisiting the argument they made in that edited collection two years ago in light of the newly released work, speaking to the ways in which Ware’s comics have either transformed in that time or are returning to the themes of his earlier publications. We hope these first thoughts give rise to a spirited discussion about a novel that will shape conversation in the medium in the years to come.

In Chris Ware’s Building Stories, loss saturates. The work is described as a “graphic novel” on the large box that contains the 14 separate comic strips, bound books, stapled pamphlets, and newspaper-sized pages that make up Building Stories, a work that moves well beyond the singularity implied by the term. Its major and minor characters dwell on and experience loss in a variety of forms: the loss of family members, pets, relationships, and limbs, as well as the less abrupt processes of losing romance, sex, weight, jobs, even home equity. Loss means a lot of things in Building Stories, and, in keeping with the text's complexity, loss is something that Ware’s characters dread, fight against, and fear, yet also something that they occasionally desire.

Building Stories finds a curious paradox embedded within loss. In one large, newspaper-sized component of the text, "loss" describes both the death of a close friend, and the triumph of shedding a few pounds; one of these losses is tragic, the other desired. This duality gives Building Stories a complexity that is rare and profound. Loss in Building Stories is a condition of life, yet it is never complete. That is, no matter who dies or what is removed, every loss leaves behind a remainder in Ware’s world. This is perhaps most visible in Building Stories’ female protagonist, who loses the lower half of her leg as a child in a boating accident. While the leg is gone, it remains as an absence on the three inter-related large drawings of the protagonist’s body in a hardback book within Building Stories. The reader cannot help but notice the leg as absence, and the absence registers, itself, as a presence, a marker of individuality. What is lost, remains.

Building Stories finds a curious paradox embedded within loss. In one large, newspaper-sized component of the text, "loss" describes both the death of a close friend, and the triumph of shedding a few pounds; one of these losses is tragic, the other desired. This duality gives Building Stories a complexity that is rare and profound. Loss in Building Stories is a condition of life, yet it is never complete. That is, no matter who dies or what is removed, every loss leaves behind a remainder in Ware’s world. This is perhaps most visible in Building Stories’ female protagonist, who loses the lower half of her leg as a child in a boating accident. While the leg is gone, it remains as an absence on the three inter-related large drawings of the protagonist’s body in a hardback book within Building Stories. The reader cannot help but notice the leg as absence, and the absence registers, itself, as a presence, a marker of individuality. What is lost, remains.

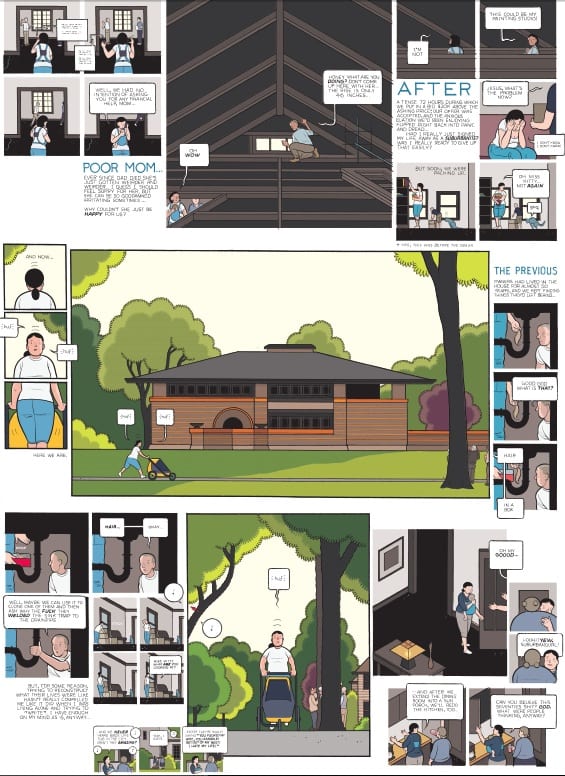

In The Comics of Chris Ware, I wrote about the Building Stories comics collected in ACME Novelty Library Number 18 and Ware’s collaboration with Ira Glass, Lost Buildings. In that essay, I wanted to demonstrate how the melancholy that Ware’s work dwells on and explores can lead to a heightened sense of history. By making a building into a character, Ware asks us to think about our lived environment on a different historical scale than we might normally do. I still think that this is true of Building Stories, though what I found different in this complete collection is how the building didn’t figure into many of the comics. Instead, we see our female protagonist before and after her residency in the apartment building that she gives voice to in cursive script. In the long newspaper-sized comic that I mentioned above, the protagonist lives in Oak Park, Illinois, a neighborhood with strong ties to modernism: it is the site of both Frank Lloyd Wright's home and studio, and Ernest Hemingway's birthplace. In Oak Park, Building Stories' female protagonist resides in a house that is not sentient, yet the house nonetheless figures prominently in the narrative. Even though the suburban home does not think in cursive, like the apartment building, the house still has a character, and an ominous one at that: death seems to close in around the protagonist in the house—her best friend from college commits suicide, her cat dies, and she flushes a baby mouse down the toilet, a moment that resonates with the character's complex feelings about an abortion during her college years.

It is clear in Building Stories that loss is not something that happens to individuals alone. Instead, loss is a kind of collective condition, and it simply exists in the world. Loss isn’t a momentary event or unfortunate occasion. We inhabit loss, like it’s a building. What this means, of course, is that loss outlasts all of us. If anything remains of our civilization, Building Stories seems to claim, it will be loss, a sense of dashed hopes, unhappy romances, missed opportunities, and all-too-fleeting joys. But, these losses themselves are records of potential and, even, happiness.

It is clear in Building Stories that loss is not something that happens to individuals alone. Instead, loss is a kind of collective condition, and it simply exists in the world. Loss isn’t a momentary event or unfortunate occasion. We inhabit loss, like it’s a building. What this means, of course, is that loss outlasts all of us. If anything remains of our civilization, Building Stories seems to claim, it will be loss, a sense of dashed hopes, unhappy romances, missed opportunities, and all-too-fleeting joys. But, these losses themselves are records of potential and, even, happiness.

In the comic originally published by McSweeney’s for the ipad as “Touch Sensitive,” glass-helmeted people from the future watch the second-floor residents of Building Stories' central apartment building, a couple on the verge of breaking up, with the aid of technology that can read "memory fragment[s]" from an "area's consciousness cloud." This is, I think, less a whimsical comment on the future than it is an articulation of Building Stories’ fundamental worldview—that our lived experiences and habits, understood generally as a sequence of losses, will outlive each of us. Loss remains accessible to others, just as buildings do after their current inhabitants move out or pass on.

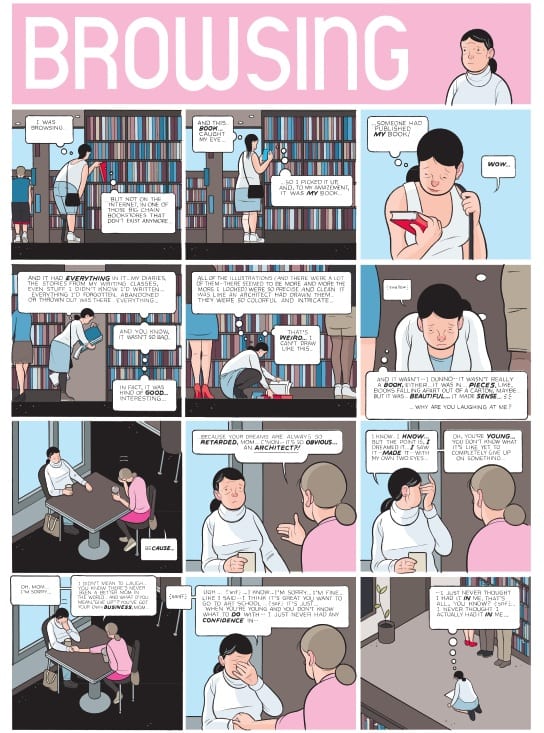

In one moment, the female protagonist is trying to decide what book to bring on a flight. She discards a number of canonical works and authors, Moby-Dick, Ulysses, Proust, Dostoevsky, and Nabokov, thinking, "Fuck! Why does every 'great book' have to always be about criminals or perverts? Can't I just find one that's about regular people living everyday life?" Ware is trying to represent that reality, it seems, going so far as to invoke Building Stories itself in the text. In a different part of the text, the female protagonist describes a dream in which she stumbles upon her own book in a bookstore: "And it wasn't—I dunno—it wasn't really a book, either…it was in…pieces, like books falling apart out of a carton, maybe…but it was… beautiful…it made sense." The main character in Building Stories dreams, and even writes, the very book that we are reading at that moment, encountering her own life in a way that is filled with recognition and admiration, yet also, ultimately, loss, as the page concludes with the female protagonist on the floor of the bookstore, sobbing, "I just never thought I had it in me."

In one moment, the female protagonist is trying to decide what book to bring on a flight. She discards a number of canonical works and authors, Moby-Dick, Ulysses, Proust, Dostoevsky, and Nabokov, thinking, "Fuck! Why does every 'great book' have to always be about criminals or perverts? Can't I just find one that's about regular people living everyday life?" Ware is trying to represent that reality, it seems, going so far as to invoke Building Stories itself in the text. In a different part of the text, the female protagonist describes a dream in which she stumbles upon her own book in a bookstore: "And it wasn't—I dunno—it wasn't really a book, either…it was in…pieces, like books falling apart out of a carton, maybe…but it was… beautiful…it made sense." The main character in Building Stories dreams, and even writes, the very book that we are reading at that moment, encountering her own life in a way that is filled with recognition and admiration, yet also, ultimately, loss, as the page concludes with the female protagonist on the floor of the bookstore, sobbing, "I just never thought I had it in me."

Yet there is also an optimism to Ware's masterpiece. Even Branford the Best Bee in the World, the star of a stapled pamphlet and a newspaper in the volume, lives on, transformed into Branford the Benevolent Bacterium after he is squashed. Building Stories seems to say that loss is the umbrella under which we can all find commonality, and it is also, paradoxically, the condition in which we are the least likely to look for connections to others.