Flook, which appeared in British newspapers for over 40 years, may be the greatest unlauded daily strip of the post war age, and is certainly among the most criminally uncollected. The disarming appearance of its title character, somewhere between a piglet and a mole, conceals a world of keenly observed and hilarious high satire that stands complete comparison with acknowledged greats of the field such as Pogo and L’il Abner. Uniquely the strip offers a mainlined, as-it-happens comic strip almanac of British culture, politics and society during that enduringly fascinating epoch of modern history that takes in Queen Elizabeth’s coronation, The Beatles and the coming of Margaret Thatcher. It achieved this thanks to a succession of savvy script-writers and the brilliant work of its sole artist and caretaker Trog, the penname of Wally Fawkes, one of British cartooning’s best-kept secrets. A complete reprint (or a representative collection at the very least) would be an eye-opening read for anybody with an appreciation for the newspaper strip format in its zenith, or who simply fancies a first class tour around the bustling essence of mid to late twentieth century London.

Flook originated in 1949 after the proprietor of the UK’s Daily Mail, Lord Rothemere, took approving note of Crockett Johnson’s Barnaby and expressed a desire for a similar series to run in his paper. Mail journalist Douglas Mount duly devised the story of a young boy named Rufus, whose simple wish for a pet is thwarted until the day that Flook, a prehistoric and chameleonic “small furry creature” literally falls out of the child’s dream. The 24-year old Fawkes was assigned as artist, and drew these formative chapters with a dark expressive line and parochial detail more associated with fine art illustration than strip cartoons. Soon Rufus and his new best friend were embarking on a series of exploits that found boy and creature at turns encountering ghosts in The Tower of London and travelling to a South Sea island on the trail of a millionaires long lost daughter, Flook’s special power to change into anything often playing a key role in proceedings. However, within a few years (and a change or two of scriptwriters), the pair’s daily adventures had started to stray from such strictly storybook escapades into decidedly more satirical terrain.

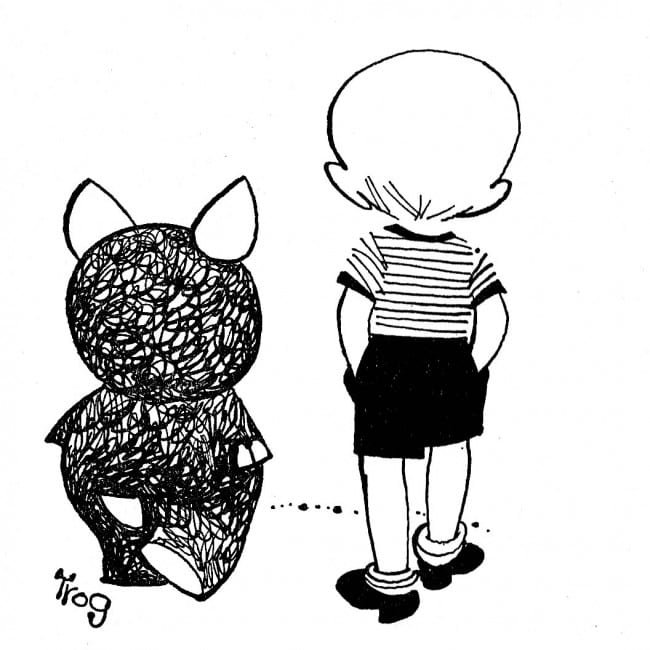

As the strip’s unbroken continuity progressed, Flook gradually outgrew his animalistic attributes (and for the most part, his shape-shifting ability), to make his name and his home in London as a somewhat unlikely figure of considerable cultural and political influence. At once a pro-actively progressive liberal and a bon viveur with paws in every level of society, he always retained enough of the primordial remove of his origins to keep one step ahead of his peers and foes. In contrast, Rufus remained a child; while still Flook’s best friend and enduring foil, he seemed to become ever more innocent and epicene as Flook’s world grew layered with the intrigues and vices of London in the raw.

Indeed, Flook presents perhaps the most acutely observed and complete London ever seen in comics history: over the years the strip accrued a sizable supporting cast; including robust archetypes of every strata of British society, from the rough cut crook Bodger to the multi-purpose establishment man Sir Montague Ffolly, taking in social climber Scoop and his wife Prudence, unscrupulous bar-propping journalist George Jabb, and many more, to say nothing of the numerous parodies of contemporary celebrities and politicians. Each really comes alive in the dialogue, which is infused with a keen ear for the appropriate London vernacular and spot-on cultural reference points. This social veracity was reflected in the strip’s appearance; by the early '60s Fawkes’ art had achieved the perfect mean between stylisation and pin-sharp observation, at once modishly iconographic and richly illustrative. His striking use of real life London locations, filmic compositions, and carefully constructed likenesses lend every three or four panel strip a perfect cartoon realism that is both evocative of the moment and immediate to the modern reader.

With this singular cultural sweep, and the combined guile and lack thereof of its two leads, Flook was well-primed to satirize every trend and concern of the day, throwing up some truly inspired storylines. Sometimes the strips’s blend of the cultivated and contemporary tended merely towards the whimsically ingenious - for instance, when threatened by the devilry of the modern day vacuum cleaner riding witch Lucretia, Flook has the idea of fashioning a mobile magic circle from a hula hoop. In another strip Alice Liddell falls through the looking glass into 1966, and has to re-invent herself as a masked superheroine to prevent a bombastic point-missing movie of her adventures making it to the big screen (if only she’d fallen into 2010...)

Other moments simply knock the reader for six with their joyful anarchy, like the strikingly fourth -wall breaking strip of 1955 where Flook and his rival of that month Mr Sprott are shown playing cards while the Daily Mail is on strike, waiting for their cue to resume their roles.

But the series is at its most affecting when it takes on the allegorical mantle of a great modern fable, such as when Flook moves to a new town, only to encounter racial prejudice towards his small and furry kind, and it takes the populace turning overnight en masse into Flooks for them to change their mind and... start persecuting Rufus instead; or when the duo return to the Stone age and see the cold war stalemate paralled in the impasse of two groups of cavemen; or the moment in a 1961 sequence which sees the senior management behind the purposeless but pervasive mass consumer product “Instant Sludge” revealed, to Flook’s horror, to be literally faceless.

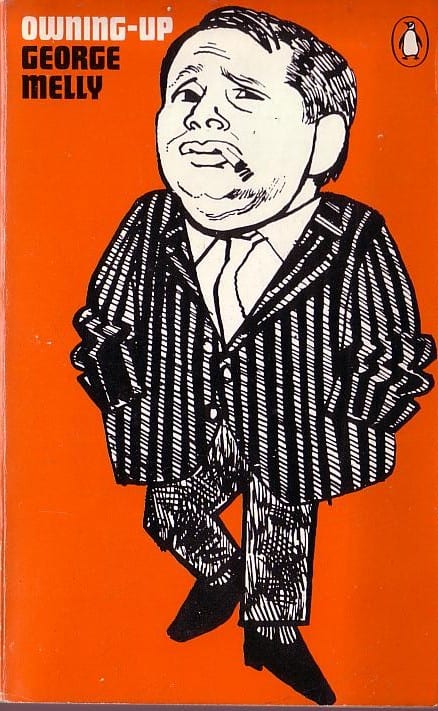

Flook’s distinct invention and cultural depth was thanks in no small measure to the series of scriptwriters who had succeeded Mount; most prominently many of the scenarios outlined above were the work of the gregarious jazz vocalist, pataphysician and surrealist George Melly, who lent the mature Flook much of his own character, interests and favoured drinking establishments. But the roll call also includes the author of Whiskey Galore, Sir Compton Mackenzie, film critic and television personality Barry Norman, Marty Feldman’s writing partner Barry Took, Jazz bandleader Humphrey Lyttleton and Billy Liar author Keith Waterhouse. Of the endeavours of each of these men entire volumes could be devoted (and in most cases have been). But always providing the visual component and steering the strip over its 40-plus years was Wally Fawkes.

Born in Vancouver in 1924 but a resident in the UK since 1931, Fawkes’ talent for illustration was apparent from an early age, and after his work was discovered by the Daily Mail’s political cartoonist of the day, Leslie Illingworth, he commenced his professional career on 24th June 1945— his 21st birthday— initially drawing editorial column breakers before commencing work on Flook. He balanced the first decade or so of his cartooning career with an equal commitment to playing clarinet with several popular New Orleans-inspired jazz groups of the period (including one led by Humphrey Lyttleton), being one of the instigators of what would become known as the British Trad Jazz movement. Fawkes always noted that “the cartoonists know me as the one who plays the clarinet. The jazz people say I’m the one who does the cartoons.” However from the late 1950s onwards, Fawkes focused his professional interests firmly on drawing, and expanded beyond Flook and the Mail into creating political cartoons for more left-of-centre UK papers such as The Spectator, The New Statesman and The Observer, as well satirical magazines like Punch and Private Eye. Renowned by the likes of Raymond Briggs amongst others as one of the UK’s finest caricaturists, his solid, note-perfect likenesses and subtly profound commentaries stand in controlled contrast to the more conspicuously rambunctious work of near contemporaries such as Scarfe and Steadman, and constitute a remarkable body of work in their own right.

After exactly 60 years, Fawkes retired from cartooning in 2005, and at 89 now resides in retirement in the Camden borough of London. He was recently gracious enough to grant me a telephone interview about Flook and his career. -- Adam Smith

Over the years, Flook gradually developed from being a children’s strip to a more adult-orientated satirical strip. How did that come about?

Going from a children’s strip, that happened quite early on... Douglas Mount was the first one who had the idea of the little boy and the little animal who fell out of his dream, which was the starting point; but I wanted it to be more social comment, a bit more reflective of what was going on.

So that’s always what you wanted?

Yeah, and after Douglas Mount we got Bob Raymond; he was Australian, he was a very good journalist working for Picture Post, so he was well up with what was going on; you know, world politics, and we did a story in ’53... that was the big coronation year, and Everest, so we did the Abominable Snowmen, but we made the snowmen actual snowmen, and the fat ones lived above the snowline, and the thin ones lived just beneath the snowline, and Flook had to sort of make it more even; so he told the thin ones to insult the fat ones, and they all got angry and threw snowballs at the thin ones. They lost weight and the thin ones gained weight; that was pure communism! But the Daily Mail didn’t seem to notice the implications. That was the first political one.

And did you carry on in that vein for then on?

Yeah; well you know, it wasn’t always as loaded as that... and then, the Daily Mail wanted to increase their sales in Scotland, because there was a noticeable shortage of Daily Mail readers north of the border, so we got Compton Mackenzie in, and he did a re-write of Whiskey Galore.

He must’ve been quite old when he worked on the strip.

Well he seemed old... how did he still get about? He was 70. That seemed so old then, but now, I look back on 70 as... well, not the first flush of youth, but certainly, the prime of middle age! You know, you’re approaching your peak at 70.

Did you meet a lot to work or was it done through letters?

No, I’d meet Compton Mackenzie, he’d come to the house; and then, he invited me down to his place in the country...but the amount of whiskey we got through!

It’s not very conducive to drawing, is it?

Woah, I was shattered the next day! But it was all in his stride. And then Humph [Humphrey Lyttleton] came, because I was standing next to him on the bandstage... he was the nearest person! But that was good, we got back to Flook going back to caveman days, and they invented the club, but with a nail through it, which was the equivalent of the atomic bomb... so Flook tried to make them outlaw it, or it would be the end of civilisation as they didn’t know it!

Did you find it a challenge to draw a week’s worth of Flook strips while regularly playing jazz gigs?

Keeping the playing and the drawing together, that really became more difficult. There was a time in ’54 when I had an offer to go to Geneva to play with Sidney Bechet with a Swiss band, and to produce a stockpile, because that was about three or four weeks, everybody was filling in--I was doing the outlines, and everybody was filling in, like Neb, [Ronald Niebour]. They all got together and supplied me with a stockpile of strips so I could go away to Geneva and play with Bechet. Then from about ‘55, our band became more and more successful, the touring increased, there were continental tours, and I was heading towards a nervous breakdown, the strain of it all was just too much, and I knew what I had to do. I knew I wouldn’t make any money out of playing; unless you’re a bandleader, you just don’t. And to keep the music, which I loved, safely on one side and really concentrate on the drawing. Which was a very good decision. So I left Humph in ’56.

Have you toured since then?

For a while I had a band called the Troglodytes. We did the occasional tour up north; it wasn’t really touring, just the occasional weekend, like a Saturday night gig. The Trad Jazz of Chris Barber was sweeping, and you had to have banjo. We got a bit tired of that noise, and we were trying to move away from that painting-by-numbers school of music. Gradually it came back to the pub, and I’ve spent the rest of the time playing in pubs. The occasional concert, but now I’m not really playing at all--I decided to quit while I was still at the bottom!

Then we get to George Melly, who took over from Humphrey Lyttleton...

The different writers brought different things to it. Well, Flook became George.

I thought that.

Did you?

Yes, very much… the way he acts in those strips, he’s a kind of social butterfly, appearing on tv…

And going to all George’s clubs... you know, Muriels on Dean Street, and the French Pub, Wheeler’s restaurant; all of George’s circle of watering holes.

Did you see him a lot socially during that period?

Oh yeah, he was my favourite character in fiction! Because we were so different. Whereas I found it difficult laughing out loud, George could smile out loud! A tremendous outgoing personality.

That is quite often considered to be the peak of the strip, the George Melly years.

Yeah that was when it created most attention I think.’56 he started, and by the early '60s, there’s the Profumo affair...

“The Clip-On Bowtie Affair”...that was the Flook version -

Oh yeah, that’s the one.

He did it right through to ’71. So he did the whole of the '60s.

Yeah.

Particularly with those strips, you were able to tackle such adult themes, but it was still a children’s strip, it’s very cleverly done, it’s like a fairytale.

Yeah, I think we wanted to amuse the parent as well as the offspring.

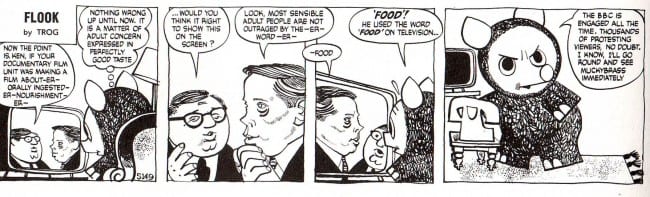

There’s the strip about Kenneth Tynan, [Critic notorious for being the first person to use the F-word on British television] where they ban “Food” as a 4-letter word... do you remember that? Flook becomes a food critic on TV, but he sees all his co-hosts being gluttonous, and they turn into pigs before his eyes, so he decides to have a moral crusade against food, and the 4-letter word “food” is banned. Then Kenneth Tynan is on TV, and he uses the 4-letter word “Food” and creates an outrage... I thought it was very clever the way children could read that, and it was also a very adult satire.

Well, that was tremendous. George was very sharp.

Another quality I love about Flook is how the reader can build up a vivid picture of the times and places featured when reading the strips, especially London in the '50s and '60s... I was wondering if this kind of reality was particularly important to you, and how much real life research you would do for the stories.

You’re talking about location, and I did, I got a huge amount of pleasure , whenever they cropped up, and suggested a real place, I’d get on my bike and draw it. Y’know, of little churches... there’s one little church just outside St. Pancras station, a very pretty little church, and I remember drawing that , to give it interest, so people could say “Hey! That’s our church” or “that’s our pub” and make them real places. There’s a pub called the “Hooray Henry” which is really The Castle near Baker Street, so I went and drew the outside of that.

Does that still exist?

Yup.

Okay, I’ll have to do a Flook tour of pubs!

Not many of them, but yeah, the Windsor Castle does.

That attention to detail really lifts the strip - with a lot of newspaper strips, especially humour ones, you look at them and they don’t have that depth; with Flook you really feel it’s a whole world of London you can step into...

The reason for that is, I was more of an illustrator than a cartoonist, certainly in the early days. I used to see Punch, and then The New Yorker, but I was really much more interested in illustration. That’s what took me to Camberwell to dig stuff like John Minton, whose drawings I loved.. his paintings weren’t quite so fantastic - well they were brilliantly done, but his pen drawings I thought were fantastic.

I can see the influence in the pen drawings with your backgrounds. I was also wondering if you were influenced by any fine artists... some have also said the backgrounds look a bit Cubist, or Georges Braque-

Errrr, that would’ve been perhaps influence without being aware of it. The Picasso type, I never got into that. I was more interested in what was going on outside my mind rather than what was going on inside... they became more and more psychological and Freudian. I think it was Robert Benchley, or Thurber, who wrote a book called Leave Your Mind Alone, which I thought was marvellous, you know, good advice. I liked the Americans, you know, Charles Addams, Steinberg...

So it was the New Yorker kind of cartoonists you were influenced by?

Not necessarily, because I was influenced by some of the English ones, like Emmit, and Pont. I learnt an awful lot from Leslie Illingworth, who was my fairly godfather!

You can see his influence not so much in the earlier stuff, but in the later caricatures...

You gradually develop. How Rufus and Flook developed, it wasn’t a conscious thing at all, but they did, just by doing it, doing it, doing it, so many many times, they both became simpler, more rounded...

And they changed because, at the start, they were on the same level, best friends, whereas later, when Flook became more of this George Melly type, he would sometimes leave Rufus at home. I felt a bit sorry for Rufus.

Yeah... I think now, if I was doing it now, I’d spend a lot of time with Rufus trying to explain away to the immigration people, how he came to the country: “where’s he from? Where are his papers?” - “Well he fell out of my dream!” - “Oh yes, Oh yes, a likely story”... you could have a lot of fun with that. But there weren’t those problems then. We were inviting boatloads of people from the West Indies, to run our London transport and hospitals.

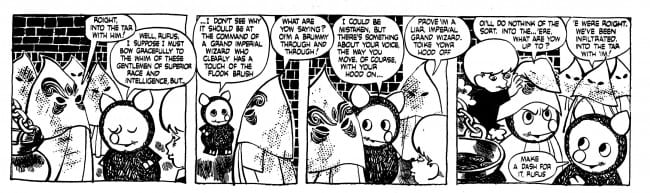

That reminds me of another story... in “Flook For A Neighbour”, where he moves to the north, and Flook is shunned for being small and furry, but then Lucretia visits, and she turns everyone small and furry overnight; you’ve got the Klu Klux Klan in there, because all the villagers have been turned into Flooks, but they think they’re the superior race..

Well the Daily Mail then was a much more liberal paper. It had people writing on it who were sort of liberal left: Bernard Levin, and Alan Brian; the critics were definitely of the left...

When would you say it changed to being more right wing...

Well, the very day in 1971 when David English took over as editor and he got rid of all us lefties. Because I was doing the political cartoon that I’d inherited from Leslie when he retired in ’68, he got rid of me as a political cartoonist— he thought I was trying to bring politics into it! He got Mac in, who was nice and safe; he amused the suburbanites.

He’s still doing it, isn’t he?

Yes, he’s still doing it. And Barry Norman went, cos he was a friend of [Mail journalist] Julian Hollands. They cleansed the stables in one fell swoop.

Now 1971 was the same year George Melly stopped writing Flook: I assume that wasn’t a co incidence?

No, It was un-connected: that was the year George Melly decided to go back on the road again as a singer, so he fled off, so, cheekily, I was thinking who I should I get after George - and there was Barry Norman who’d just been fired! So I asked him to do it, so they had to re-employ him again, and that didn’t go down at all well. They tried to bring in Auberon Waugh, who was a right-wing satirist from Private Eye, and I said “no I’m happy with my friend Barry”.

How long was Barry Norman on it?

Two or three years. Barry wasn’t the social animal that George was. He did some good things... it was political rather than social.

After George Melly left, there were a lot more caricatures of political figures of the day.

That’s right. And that annoyed David English too. Thatcher was in the cabinet, so we pounced on her as a ridiculous figure, as we did everybody else. You know, Harold Wilson, they didn’t mind that, they didn’t mind us having fun with all the Labour chaps, so we carried on. But they did mind with the Tories.

After Barry Norman, it was Barry Took? He was a couple years on it too?

Yeah... I think after George, two or three years was about it.

And after him, you took over writing for a bit

Yeah, I tried, but I think the wheels had fallen off by then. There was some good stuff with Barry Took... he did "The Peasant’s Revolt."

That’s one of the ones that’s in a book... that’s got Thatcher in it, and Tony Benn.

Yeah, and Michael Foot with Wat Tyler. That was nice.

There never was a comprehensive collection... there’s only a few books, and all with different publishers...

It didn’t have that big appeal, it was a minority interest. Something like Peanuts, it had enormous appeal because it was immediate. It was simple, and very funny; it was marvelous, but you didn’t need to know what was going on. It appealed to the whole of mankind.

There’s a tradition in America where strips like Peanuts are lauded as masterpieces, and rightly too. I think it’s a shame that Flook isn’t accorded the same cachet, as it’s such a deep and rich social history.

Fantastic, it amazes me the amount of interest in it. I remember really pouring myself into it at the time, and sustaining it, but you’re not aware of anybody actually reading it... seems a bit self indulgent!

Do you have any memories of drawing the very last Flook for the Mail and of why the strip ended?

The last strip I did in the Mail, was when David English thought that was going over the top.

Do you remember Zola Budd, the South African runner? David English brought her over to run in the Olympic games of that year, breaking all sorts of rules and regulations. And I did a strip of Flook saying to Rufus “I see Zola Budd’s just broken a new record” “Really, what’s that?” ; “She’s just jumped five years in three weeks!”... that was a strip that didn’t appear actually, but I’ve still got it. It was almost like a suicide note. Get me out of here! David English said that was it. I was sad, it was the end of Flook. But I said to him “At least my friends will speak to me now” as a parting.

After that, Flook went to the Daily Mirror, with Keith Waterhouse. What did he bring to it?

He turned some of his newspaper columns he had when Thatcher came in into a story: so we sent up The Rovers Return, and we did a cod thing of [long-running British soap opera] Coronation Street; it became “Confrontation Street”. But it didn’t appeal to the Daily Mirror reader, who wanted more direct, slap in the face pronouncements. And the owner, who later fell off his boat, Robert Maxwell, he couldn’t figure it out at all... he could not make head nor tail of it. Why it went to the Mirror was, his wife loved it in the Mail, and she used to read it to her sons when they were young children. So Flook has a lot to answer for! But he pulled the drawbridge over.

It carried on for a little while in the Sunday Mirror? Even into the 90s?

Yeah, just as a one-off, but it didn’t work. I think it had run its course. It needed fresh legs.

It’s amazing it ran for 40 years... it’d be great to have it collected just to read 40 years of social history!

All good fun, and great to look back on.