Social media and online publishing have helped connect cartoonists with readers who might never have found their work otherwise. Thanks to the free access afforded by platforms like Twitter and Instagram, comic panels can be distributed and shared within minutes of completion.

But while there is something to be said for the digital release of comics, subsequent physical publication can afford readers a new and equally valuable perspective on the material. By examining four comics that were initially published online before later receiving print editions, a more comprehensive understanding of these varying perspectives can be achieved.

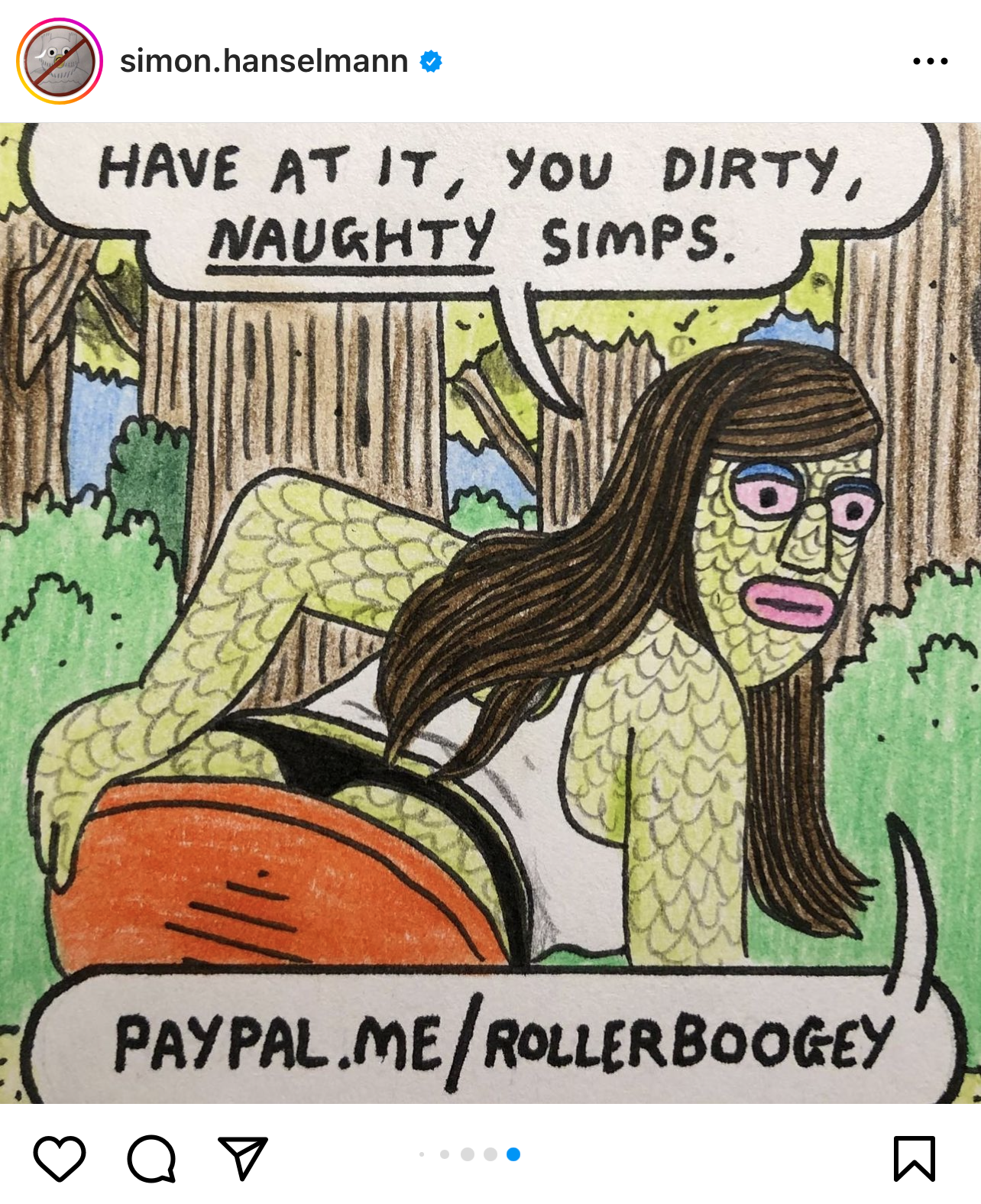

The serial aspect of Crisis Zone by Simon Hanselmann lent itself particularly well to Instagram. Beginning on March 20th, 2020 and running through December 22nd of that year, Crisis Zone was updated on a near-daily basis.

Its consistency meant that followers on social media would leave agitated messages on the few days where, for whatever reason, Hanselmann would not post an update. On several occasions, it became necessary for Hanselmann to post an Instagram story that assured followers that Megg, Mogg and the rest of the gang in Fucktown would indeed be returning the next day for another ten panels of their COVID-19 endurance run. Readers didn’t just react when there wasn’t new material, either: many must have set alerts for Hanselmann’s Instagram account, because comments would begin to appear as soon as a new day’s entry was posted, either reacting to the comic or simply celebrating its arrival.

Crisis Zone followed a strict format: a dozen panels per page. However, due to Instagram's restrictions on the number of images that can be included in a single post, Hanselmann was only able to post ten panels per day. Hanselmann capitalized on this limitation. Omitting two panels per page from each daily post, the story was nevertheless able to unfold in an uninterrupted manner. Simultaneously, Hanselmann generated anticipation for the “director’s cut” of the fully-intact physical release.

“Classic drug dealer model, get 'em hooked with a free taste and then start charging once you've got 'em addicted,” he said in an interview I conducted at Comics Beat.

It wasn't just two new panels per page that appeared in Fantagraphics' physical release of Crisis Zone. The backmatter included four additional pages (48 more panels) featuring events from early 2021, including an allusion to the insurrection at the United States Capitol. In addition, a dozen pages of cramped, handwritten “Director’s Commentary”, segmented into narrow sections referring to specific pages, offered some deep-dive insight into Hanselmann’s creative process, his experiences during the pandemic, and how the two dovetailed to create the unique narrative of Crisis Zone.

As if all this weren’t enough to bolster the physical release of Crisis Zone, preorders for the book through Fantagraphics arrived in a specially designed box featuring the title and a “caution” design, and included the Crisis Zone: 2022 Action Calendar!, which offered 12 months' worth of new images and captions with Animal House-style epilogues revealing what was in store for the COVID survivors a few years after their graphic novel had concluded.

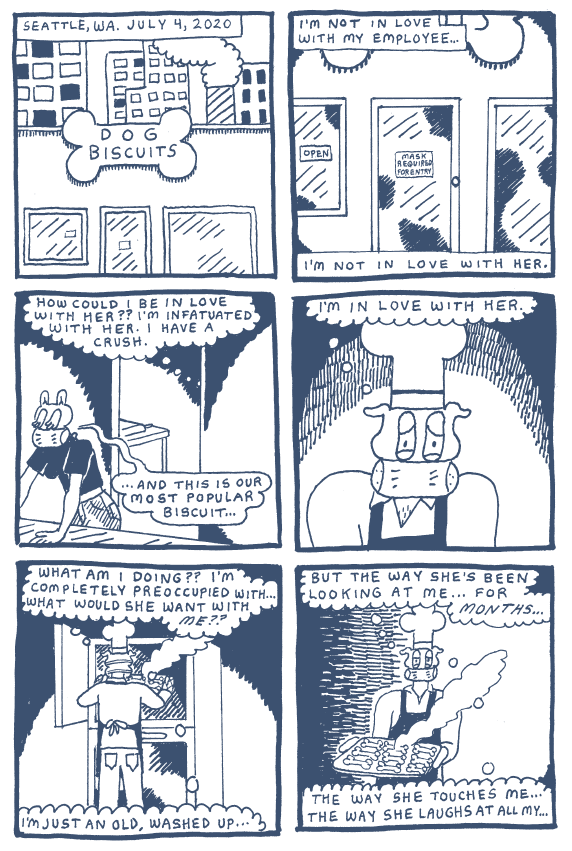

While Alex Graham also released Dog Biscuits via Instagram, her comic utilized the platform in somewhat different ways - and these decisions left their mark on the physical graphic novel. Like Crisis Zone, there were also near-daily updates for Dog Biscuits, once it began - but unlike Crisis Zone, on Graham’s most productive days, there could be multiple pages.

In part, this was thanks to the fact that each page of Dog Biscuits features six panels, which allowed for the entire page to be uploaded in a single Instagram post (unlike the selection of panels from Crisis Zone). The resulting effect on the internal rhythm of the story is acknowledged in a text prelude to the print edition. Just as a newspaper comic strip collection retains remnants of the structure imposed by the funny pages and the rhythm created by a daily release, the hallmarks left on Dog Biscuits by the natural boundaries imposed by its release via Instagram remain evidence in print form.

However, Dog Biscuits demonstrated one of the innate hazards of releasing a comic one page at a time via social media. With user comments and “interaction” being an expected part of the Instagram experience, some of the internet’s most obnoxious individuals found their way to Graham’s comment sections.

Like Crisis Zone, the measured release of Dog Biscuits gave the narrative and characters a chance to breathe, and the serialized format gave readers desperate for an emotional escape from COVID lockdown something to look forward to day after day. But the aforementioned obnoxious individuals used the fundamentally incomplete picture provided by serialized storytelling to criticize the decisions made by Graham's realistic characters, sometimes replete with suggestions of consequences that could even include death. When presented as a graphic novel, the reader’s experience with the graphic narrative is not impugned by puerile outside commentary.

Furthermore, the physical release gives Dog Biscuits the chance to have the last word on those who had maligned it during the period it was released on social media. In an afterword by Graham, she explains that she had initially planned to quote some of these detractors in the back matter. Instead, the physical release of Dog Biscuits includes an essay by Lane Yates addressing the social media backlash in an honest and insightful manner.

While Crisis Zone and Dog Biscuits may have been defined by their COVID lockdown-era release tenure, the comics by Grace Gogarty included in their Little Tunny’s Snail Diaries predate the pandemic by several years. Released on Twitter and Instagram, Gogarty’s comics are generally four panels long and presented in a two-by-two square.

Both Crisis Zone and Dog Biscuits were posted one panel per Instagram “slide”. While Gogarty uses this strategy when posting their comics to Instagram, they also consistently post their comics as a single image on Twitter or as the concluding Instagram frame. These posts present the comics in a similar layout as they are presented in the book.

However, the Silver Sprocket print edition of Little Tunny’s Snail Diaries has an especially unique element that could not be accomplished with anything but a physical release. It is secured with a small silver lock that can be opened using one of the two included keys, evoking the secret-keeping measures used by childhood diaries.

While anyone can easily access the comics Gogarty posts on social media, the physical release’s lock-and-key security demands that the reader reckon with the book as a physical object before they can access the comics contained within. This adds a special emphasis to the personal nature of many of the Snail Diaries comics, which recount real-life events experienced by Gogarty through their snail alter ego.

In addition to comics, each page of Snail Diaries includes some new material in the margins, which can either take the form of a line or two commenting on the comic or a Sergio Aragonés-style marginal drawing. While Gogarty will often tweet commentary alongside the comics as they release them, the combination of the diary-style lock and the handwritten notes or hand-drawn marginalia emphasize the intimate nature of their comic strips.

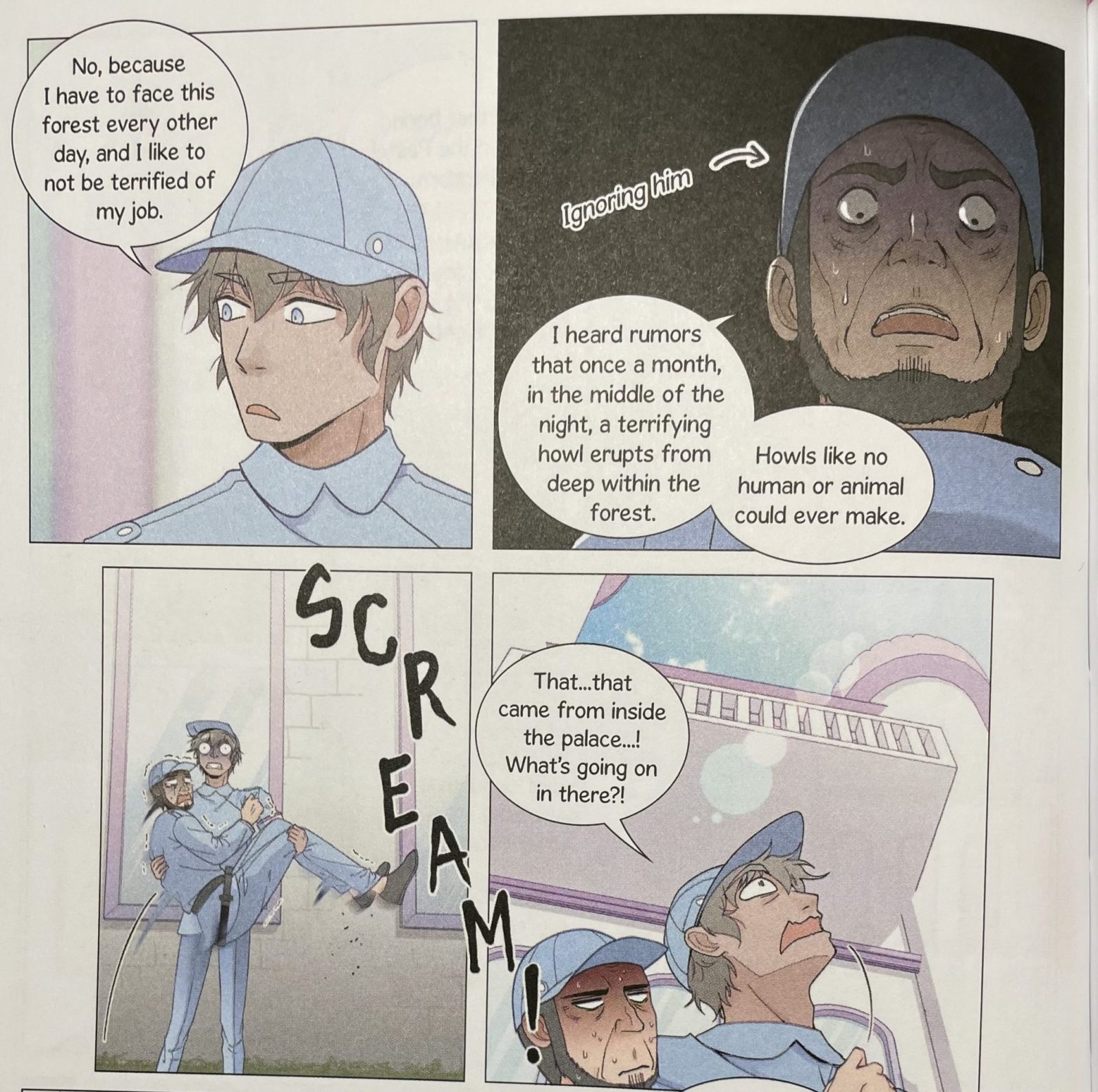

In contrast with the previous three examples, which were all initially released via social media, Cursed Princess Club by LambCat was originally posted on WEBTOON. While posts to Twitter or Instagram can be more directly adapted to the paper page, WEBTOON’s scrolling format means that reformatting is a necessity.

The print version of Cursed Princess Club has given LambCat the opportunity to learn from the WEBTOON Unscrolled team responsible for the physical adaptation, including executive editor Bobbie Chase and layout designer Niko Dalcin. According to LambCat, collaboration on this process has emphasized one of the major differences between the online scrolling format and the printed book. By contrast to the limitless gutter space afforded by WEBTOON, and the indulgent pacing that can be achieved by utilizing it, a physical adaptation demands that all of the dialogue fit on the page alongside the art, rather than occupying the essentially infinite space available between panels online.

It isn't just the scrolling format that’s unique to the online version of Cursed Princess Club. Each episode of the WEBTOON release also includes accompanying music. While many aspects of an online comic can be preserved through a physical adaptation, the technology that makes those greeting cards play music doesn’t seem to have developed far enough to include this one in the graphic novel.

In addition to connecting with new audiences who might not be internet-savvy enough to have located the comics earlier, the physical release of an online comic can also afford the chance to polish or re-do earlier drafts of art that the cartoonist might, for whatever reason, have concluded was unsatisfactory. While re-doing some of the art is unavoidable for a physical adaptation of a scrolling comic like Cursed Princess Club, both Dog Biscuits and the Snail Diaries took advantage of this opportunity as well.

However, the vitriol-spewing commenters who harassed Graham during the online release of Dog Biscuits help emphasize one of the most important point of differentiation between webcomics and subsequent physical adaptations. Even if you yourself are not directly interacting with a social media post of a comic, you are experiencing the sequential narrative as part of a larger community like viewing a movie or play in a theater.

For better or worse, this leads to being influenced by other people’s reactions, whether it's just an assumption based on the number of “likes” a particular post has received, or a strong emotional response to a troll’s stupid comment. By contrast, reading these comics in book form offers a more intimate experience. While the cartoonist cannot receive the same kind of immediate feedback from a reader who is experiencing the comic through a physical release, for the reader a venue that is unclogged by other people’s comments and opinions can offer an uninterrupted connection with the work produced by the creator.